The Sounds of Pageantry

Introduction

In sheer scale of sensory experience, few early modern events could compare to London’s pageants and processionals. Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century royal entries and Lord Mayor’s Shows were acoustic assaults—just about the loudest things you could hear in the seventeenth

century. Instead of jet engines, sirens, and rock concerts, early moderns found themselves

overwhelmed by trumpets, drums, fifes, and gunfire. These intense sounds, together

with speeches, poetry, dramatic scenes, music, and the noises of teeming crowds, filled

London’s soundscape and helped to define the experience of pageantry.1

We can hear the traces of this soundscape in diaries, descriptions, and records including the correspondence of Orazio Busino, chaplain to the Venetian ambassador, who witnessed a Lord Mayor’s Show when he traveled

to London in 1617:

The [Lord Mayor2] made his progress with the greatest possible pomp he could devise, always alluding to his line of trade with huge expenditure [...] We watched as a large flotilla, including the big vessels already mentioned, made an appearance accompanied by innumerable small boats of sightseers [...] Accompanied by thundering canon [sic] and fireworks, a very numerous and well-appointed group of musicians sang and played on fifes, drums, and other instruments. They were rowed swiftly upriver with the swelling tide, to the constant peal of firing ordnance.

(Busino 1265-66)

Busino recounts the sea spectacles on the Thames that preceded the Lord Mayor’s processional along London’s chief thoroughfares, from the river to St. Paul’s Churchyard, eastward along Cheapside, and ultimately to Guildhall, the seat of the City’s government. Coronation entries proceeded in the opposite

direction, from the Tower of London, westward along Cheapside to Temple Bar, and on to Westminster. The

thunderingsounds that Busino describes must have commanded the ears of everyone—from the rulers and aristocrats in the procession, to the guildsmen lining the pageant route, to the masses surrounding them.

A great variety of sounds made up the soundscape of early modern pageantry. Busino alludes to the harmonies of

well-appointedmusicians (described in

Musicbelow); their music would have ranged from the melodious voices of child singers to the piercing blare of trumpets. Busino also mentions the

constantexplosions of fireworks and gunfire, and he goes on to note that

the insolence of the crowd is extreme,with its noisy,

chaotic mixtureof people (Busino 1266). Amidst all of this tumult, he scarcely alludes to the refined verse and elaborate speeches that the leading poets of the day fashioned for outdoor pageants, to be spoken aloud. These diverse sounds did not always work to a unified purpose: some sounds blasted out a declaration of royal authority, while others asserted the power of livery companies, allowed poets to articulate didactic agendas, or arose from the revelry of bustling crowds—sometimes all at once.

Silence

What do overwhelmingly noisy pageants have to do with silence? The poets and artisans

who designed London’s royal entries and Lord Mayor’s Shows faced exactly this question when they worked to make pageants coherent for their

audiences. Each pageant was replete with symbolism: livery companies and the monarchy

incurred huge expense in order to display their eminence and grandeur in painting,

architecture, and visual design. Poets fashioned elaborate allegorical meanings through

their verses, songs, and narratives. Children dressed as mythological personae were

ensconced in ornate arches and finely wrought floats, where they delivered speeches

and performed dramatic enactments honoring their patrons. Amidst the noise, distraction,

and turbulence of the pageant day, it would have been difficult for audience members

to hear and see these elements of pageantry, let alone apprehend their significance.

(See

Crowdsbelow for first-hand accounts.)

Pageant poets addressed this problem by educating their audiences in the symbolic

meaning of the spectacles. Continuing the long tradition of festival books that illustrated

courtly ceremonies and events, poets composed printed pamphlets that commemorated

pageants and outlined their allegorical programs. It is standard for these printed

records to claim to represent all components of a spectacle completely and veraciously,

as in the title page of John Taylor’s 1634 Lord Mayor’s Show The Triumphs of Fame and Honour, which promises that

The particularities of every Invention in all the Pageants, Shewes and Triumphs both by Water and Land, are here following fully set downe(Taylor sig. A2r). All that is literally

set downe,however, is Taylor’s own writing: his idealized, linguistic version of a much larger, incomplete, or more unwieldy event. Other pageant books acknowledge that some of their contents were never performed: Anthony Munday notes that Leofstane’s description of a mining allegory in Chrusothriambos (1611) went unspoken so as to avoid an

offenſiue, and troubleſomdelay, but the speech is nevertheless printed so that readers might peruse it

with much better leyſure(Munday sig. C1v). With notable exceptions including the pageants of Thomas Dekker (as we shall see), pageant books often downplay the performative experience of pageantry. Instead of emphasizing the sonic, visual, and haptic impression on the audience, printed records tend to give the impression that pageants are objects of silent contemplation.

Thomas Middleton’s 1616 pageant Civitatis Amor, which celebrated the investiture of Prince Charles as Prince of Wales, provides an example of the silencing that pageant records made

possible. Middleton’s account begins by alluding to the sea spectacles that preceded the royal party’s arrival at Chelsea, complete with

barges richly decked with banners, steamers, and ensigns, and sundry sorts of loud-sounding instruments aptly placed among them(Middleton 35-37). As was often the case in sea spectacles of the period, these instruments included trumpets wielded by Tritons, mythological messengers accompanying the sea god, Neptune. The first lines of verse in the pageant, spoken by

a personage figuring London,endeavor to subdue the trumpets and the other sounds that filled the air, asking Neptune,

To make our loves the better understood, / Silence thy watery subjects, this small flood(Middleton 54-55).

Portrait of Thomas Middleton from the frontispiece to No wit, help like a vvoman,1657. Image courtesy of LUNA at the Folger Shakespeare Library

The rest of Middleton’s pageant book records efforts to control the sounds that are allowed into the celebration.

Neptune follows the command to silence his subjects by addressing all who surround him:

(Middleton 61-66)Not a murmur, not a sound,That may this lady’s voice confound.And, Tritons, who by our commanding powerAttend upon the glory of this hour,To do it service and the city grace,Be silent till we wave our silver mace.

The allegorical personage London then doubles down on this silencing by demanding the exclusive attention of the host

of citizens and residents in her service:

(Middleton 67-72)And you, our honoured sons, whose loyalty,Service, and zeal, shall be expressed of me,Let not your loving, over-greedy noiseBeguile you of the sweetness of your joys.My wish has took effect, for ne’er was knownA greater joy and a more silent one.

Middleton does not disguise the

commanding powerof the

over-greedynoise that threatens to disrupt the communicability of his verses and the symbolic content of the spectacle. Yet he frames his description in such a way as to clear out a space for audition, revealing how a preponderance of noise might give way to a

greater,

more silentexperience. It is no coincidence that Middleton’s muted ideal is possible not during the event itself, with its overwhelming commotion, but in a printed pamphlet that allows a poet to decide what is, and is not, recorded.

After all, silence is a cultural imposition—a way of channeling out what we do not

want to hear in a world that is constantly reverberating with sound waves. When pageant

poets and impresarios demand silence, they venture to determine what counts as meaningful.

William Shakespeare’s Prospero reveals this impulse in The Tempest, during the nuptial ceremony of act 4, a spectacle influenced by the Jacobean masque. Prospero begins this

insubstantial pageant,as he calls it, with the command,

No tongue! all eyes! Be silent(Shakespeare 4.1.59, 4.1.155). He continues to manage levels of audition throughout the spectacle, using

Soft music(Shakespeare 4.1.59 s.d.) to set the scene and insisting that the audience remain silent in the middle of it:

(Shakespeare 4.1.124-27)Sweet now, silence!Juno and Ceres whisper seriously;There’s something else to do. Hush and be mute,Or else our spell is marred.

Prospero is an expert at using art and performance as tools for power; these are the

chief means by which he crafts his dominion over others. His acknowledgement that

his spells can be marred by unwanted sounds reveals his awareness of the importance

of silence to his symbolic and political ends. Fittingly, Prospero’s demands for silent

attention are followed in short order by the

strange, hollow, and confused noisethat interrupts the spectacle, a noise associated with the play’s subaltern rebellion (Shakespeare 4.1.138 s.d.). Like the poets and impresarios of the pageant tradition, Prospero is all too aware of the power, and fragility, of silence.

Verse

Shakespeare is uncommon among his fellow poets and dramatists in that (as far as we know) he

was not directly involved in producing any pageants. Many of the period’s most prominent

poets, including Middleton, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, George Gascoigne, Philip Sidney, and Ben Jonson3 wrote the text for one or more outdoor pageants. Printed descriptions of their contributions,

full of sophisticated allusions to antiquity and eloquent lines of verse, helped poets

demonstrate their literary artistry even as a variety of sounds threatened to distract

from what they wrote.

Printed pageant records typically begin with a precise description of their honorees,

setting, commissioning livery companies, and (last but not least) poets. The title

page of John Squire’s 1620 Lord Mayor’s Show Tes Irenes Trophæa or The Tryumphs of Peace, for example, specifies the incumbent mayor, inauguration date, and location, then

announces the livery company that funded this year’s spectacle, which is performed:

(Squire sig. A1r)At the particular coſt and charge of the right

The poet receives varying amounts of acclaim. While Squire is mentioned by only his initials in Tes Irenes Trophæa, Middleton is allowed more elaborate credit on the title page of his 1613 The Triumphs of Truth:

(Middleton sig. A1r)Directed, written, and redeem’d into Forme from the Igno-rance of ſome former times, and theirCommon Writer,By Thomas Middleton.

It is Middleton’s ability to give the historical subject matter of the pageant

Formeor aesthetic shape that (according to this title page) enables him to

redeemthe past. The printed pamphlet advertises him as more refined and capable than history’s

Common Writer,a term that appears to refer not to a specific person but to a base, mundane style of recording history.

Other poets, including Anthony Munday, share Middleton’s interest in promoting their vocation through pageantry. In his 1605 Lord Mayor’s Show The Triumphs of Reunited Brittania, Munday touts his capacity to mix time periods and draw legend into the present, explaining

that the mythological personages of his devising

ſpeak according to the nature of the preſent buſines in hand, without any imputation of groſneſſe or error, conſidering the lawes of Poeſie grants ſuch allowance and libertye(Munday sig. B1r). For Munday,

the powerfull vertue of Poeſiehas a unique capacity to bear witness to the past, revive a common political purpose, and move across historical barriers (Munday sig. B1v). It is through the virtues of poetry that Brute, the mythological founder of Britain, provides a posthumous retrospective on the unification of the country under James I:

(Munday sig. Biijr-Biijv)See, after ſo long ſlumbring in our tombsSuch multitudes of yeares, rich poeſieThat does reuiue vs to fill vp theſe roomesAnd tell our former ages Hiſtorie,(The better to record Brutes memorie,)Turnes now our accents to another key,To tell olde Britaines new borne happy day.

Speaking in the rime royal verse form associated with Chaucer, Brute suggests that poetry both revives English history and provides a means of celebrating

the present.

Discription of a maske, presented before the Kinges Majestie at White-Hall,1607. Image courtesy of LUNA at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

The irony that underlies Munday’s confidence in the power of poetry here—and the printed pamphlet that records it—is

that the performance of The Triumphs of Reunited Brittania was abruptly cancelled after its floats were destroyed in a storm. The title page

of Munday’s printed record claims that the Lord Mayor was inaugurated

on Tuesday the 29. of October. 1605,as planned, but guild records from that year indicate a different story:

by reason of the greate rayne and fowle weather hapnyng [...] the greate coste the Company bestowed upon their Pageant and other shewes were in mann[er] cast away and defaced(qtd. in Sayle 83). The Merchant-Taylor’s livery company produced another version of the Lord Mayor’s ceremony soon afterward, but at a fraction of the cost of the elaborate performance that Munday describes.4 The artful poetry that is recorded in Munday’s printed pamphlet thus departs remarkably from what was spoken and performed—which helps to explain why printed pamphlets were so important for poets in clarifying and preserving their agendas.

Poets took varying outlooks on the ways in which pageant verse related to the environment

of its performance. Thomas Dekker and Ben Jonson, for example, disagreed sharply on the role of poetry in The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment of King James, James I’s 1604 coronation processional through the streets of London. Although the poets (begrudgingly) collaborated on the event, Jonson published a record, B. Ion: his part of King Iames his royall and magnificent entertainement, which details only his own contributions, with the clear position that the poet’s

pen supersedes all other dimensions of the pageant. Jonson lays bare his pedantic attitude in a passage explaining why it is unnecessary to

dumb down the spectacle so as to reach the lowest common denominator:

Neither was it becoming, or could it stand with the dignity of these shows, after the most miserable and desperate shift of the puppets, to require a truchman [interpreter] or (with the ignorant painter) one to write, ‘This is a dog’ or ‘This is a hare’, but so to be presented as upon the view they might without cloud or obscurity declare themselves to the sharp and learned. And for the multitude, no doubt but their grounded judgements gazed, said it was fine and were satisfied.

(Dekker, Harrison, Jonson, and Middleton 756-645)

Why should a poet bother to explain his verses to

the multitudeif they are incapable of understanding his verse? For Jonson, poetry provides the meaningful essence of the pageant, and the printed record of this poetry provides a means for the

sharp and learnedto remember and appreciate the significance of the event. Audiences and passersby are at best window dressing and, at worst, nuisances.

In Dekker’s account of James I’s coronation (The Magnificent Entertainment giuen to King James), on the contrary, the Genius of London suggests that all of the voices of London’s residents participate in a general chorus:

(310-13)When every tongue speaks music, when each pen(Dulled and dyed black in gall) is white againAnd dipped in nectar, which by Delphic fireBeing heated, melts into an Orphean choir.

In some ways this passage is just as pedantic as Jonson’s: Dekker’s allusion to

Delphic fireimplies that his own Apollonian pen has the power to heat and fuse the diverse voices that contribute to the pageant into a unified choir. Yet Dekker differs from Jonson by emphasizing that the voices of the multitude are part of his poetry and central to the symbolic meaning of the pageant.

Every tongue speaks musicbecause every audience member contributes to the legitimacy of the celebration, honoring the king through their collective will. Dekker’s poetry is not directed simply toward a pageant book, to be contemplated by a select and private readership. For him, pageant verse is the provenance of the entire City, to be heard, understood and created in performance.

Music

In the passage above, music is partly a metaphor for written poetry; tongues

speakmusic and are associated with the ink of

pen[s].Yet, according to Dekker’s metaphor, what makes a poet’s writing sweet are the fiery voices of the choir of Orpheus, the paragon of mythological singers. Pageant poets participate in a performative process that includes not just written records but a range of musical instruments and voices. As Dekker is well aware, a poet’s pen is accompanied by the rhythms and tones of shawms, trumpets, fifes, flutes, tabors, and drums, along with the singing of choruses and soloists.

Drie muzikanten, Heinrich Aldegrever,1538. Image courtesy of the Rijks Studio, Rijksmuseum.

Among the most conspicuous sounds that resonated through the streets of London on pageant days were the heralds and flourishes of trumpets and cornets. Lord mayor’s shows typically included two to three dozen trumpeters, supplied with banners and sometimes

horses.6 Royal entries were even more extravagant, with mythological personages trumpeting out salutes at

every turn. Drums also resounded through the streets of London on pageant days to salute dignitaries and command the attention of the crowd, from

the staccato beats of tabors to the resonant booms of kettle drums. Since the loud,

august sounds of drums and trumpets were also associated with early modern warfare,

they supplied a sense of patriotic zeal to the occasion.

Music extended well beyond these blaring

soundmarks,a term for sounds that are distinctive or specially regarded in a given social setting (Schafer 10). Sprinkled regularly through royal entries and Lord Mayor’s Shows are songs for boy vocalists that would have been accompanied by viols and other instruments. Royal entries were associated especially with consorts of lute, bandora, base viol, cittern, treble viol, and flute, now known as

mixedor

Englishconsorts. These very well funded monarchal spectacles seem to have involved a wide variety of instrumental and vocal music. In the 1604 Magnificent Entertainment, for example, Dekker’s device at the Little Conduit in Cheapside included a

music roomwith a variety of

tunes that danced round about it; for in one place were heard a noise of cornets, in a second a consort; the third (which sat in sight) a set of viols, to which the Muses sang(1728-31).

The core of the musicians involved in London’s pageants were the city waits, an official group originally derived from the guards stationed on town walls. These

versatile performers alternated between raising the town from sleep in the morning,

playing popular jigs by ear, and performing a courtly repertoire for dignified audiences.

The diverse instruments owned by the city waits gives some indication of the range of their performance capabilities. During the

early seventeenth century they played shawms, sackbuts, viols, recorders (or flutes),

cornets, curtals, violins and lutes (Marsh 121-122). Nearly all towns employed several waits, and London’s crew was the best paid and most sophisticated in the country. Thomas Morley composed his influential First Booke of Consort Leſſons (1599) with London’s waits in mind, praising them as

excellent and expert Muſitiansin his dedicatory epistle (Morley sig. A2r).

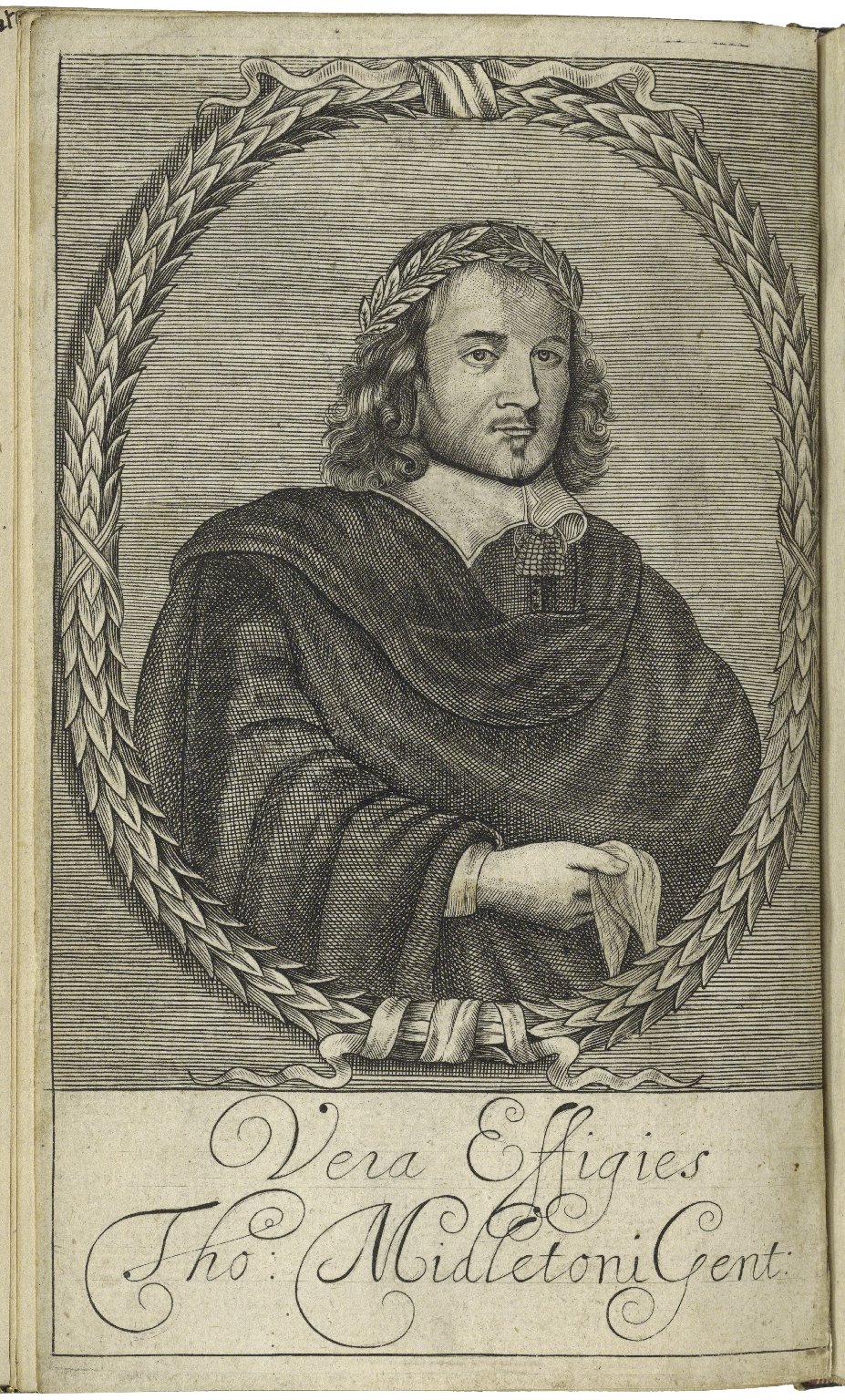

Despite the prominence of music in pageant performances, it is very rare for pageant

books to include musical notation. Although there was increasing demand for musical

notation beginning in the early seventeenth century, the trade in printed music remained

a relatively specialized venture, and pageant records (like printed drama) generally

do not expend the additional effort and cost necessary to provide specific tunes.7 Of all of the Lord Mayor’s Shows for which printed pamphlets survive, only two include musical notation: Middleton’s The Triumphs of Truth and Squire’s Tes Irenes Trophæa (see above). In both of these examples, the music consists of two straightforward melodic lines:

one for the primary melody, with the words laid below the corresponding notes, and

the other for the

bassusor viol accompaniment. Both are relatively simple tunes that would enable amateurs to reproduce pageant music in household contexts: the aim is not to cater to refined musicians but to provide a rough semblance of the melody.

![Concentum inter se, et discrimina grata sonorum aure erudita deprehendit musica, [1565]. Image courtesy of LUNA at the Folger Shakespeare Library.](graphics/early_modern_instruments.jpg)

Concentum inter se, et discrimina grata sonorum aure erudita deprehendit musica,[1565]. Image courtesy of LUNA at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Although they generally lack musical notation, pageant pamphlets frequently make reference

to music in verse and prose, providing lyrics for songs and outlining the ideals of

musical harmony as they relate to the pageant’s symbolic program. Some poets, notably

Thomas Dekker, are concerned not only with ideas or metaphors of music, but with embodied experiences

of sound. For example, Dekker’s London’s Tempe (1629), a mayoral show sponsored by the Ironmongers’ Company, comes to a climax in a clamorous, yet

concordantand rhythmical,

Lemnian Forge:

A fire is ſeene in the Forge, Bellowes blowing, ſome filing, ſome at other workes; Thunder and Lightning on occaſion. As the Smiths are at worke, they ſing in praiſe of Iron, the Anuile and Hammer: by the concor- dant ſtrokes and ſoundes of which, Tuballecayne be- came the firſt inuentor of Muſicke.

(Dekker sig. B2r)

Alluding to the Book of Genesis, where Tubal-cain is

an instructor of every artificer in brass and iron(Gen. 4:22), Dekker invites his audience to hear music in the

stroakes and soundesof urban manufacturing.

In the song that follows, we hear from the smiths directly:

(Dekker sig. B2v)The Song.Braue Iron! Braue Hammer! from your sound,The Art of Musicke has her Ground,On the Anuile, Thou keep’st Time,Thy Knick-a-knock is a smithes Best Chyme,Yet Thwick a-Thwack,Thwick, Thwac a-Thwac-Thwac,Make our Brawny sinewes Crack,Then Pit a-pat-pat, pit a-pat-pat,Till thickest barres be beaten flat.

The four-stress couplets and the onomatopoetic refrain of the song prompt an audience

to sing, stamp, or shout along. Indeed, the onomatopoeia is so thick that we cannot

help but privilege the immediate, sensory environs of its utterance. The

Thwick a-Thwacks and

knick-a-knocks are indexical signifiers: they draw our attention to what the smiths call the

Ground(

The Art of Musicke has her Ground). In the early modern period, ground denotes a recurring melodic line, usually in the bass, that underlies variation in upper parts. In the smiths’ song, our attention is directed to this background: the song’s acoustic surroundings come to be at the center of its musical meaning and experience. Thus, even though the notation for this song is not extant, we can gather a visceral sense of its music.

Crowds

However brilliant pageant music strove to be, it would have had difficulty competing

with the sounds of uproarious crowds. Orazio Busino describes the bustling scene at the Lord Mayor’s Show of 1617 as follows:

Looking below us onto the street we saw a huge mass of people, surging like the sea, moving here and there in search of places to watch or rest—which proved impossible because of the constant press of newcomers. It was a chaotic mixture.

(Busino 1266)

Busino perceives this crowd as volatile not least because of the heterogeneity of social

classes and the imposing presence of London’s burgeoning masses. Pageant crowds were a

chaotic mixturebecause they brought London’s underclasses face-to-face with its tradesmen, monied citizens, livery company officials, aristocrats, and even royalty. Although the cheering, clapping, cursing, and shouting of these crowds threatened to make poets’ verses inaudible, it was important to the success of a pageant’s political goals. Crowds legitimized the power of the dignitaries being celebrated, reinforcing the sense that the pageant was a monumental occasion and providing an opportunity to disseminate propaganda. Yet crowds could also be unsettling and even dangerous, placing officials amidst an unruly public that might be uninterested in the official subject of the pageant or resentful of those in power.8

Busino witnessed the 1617 Lord Mayor’s Show from the relative safety and privilege of an upper-story building,

yet he emphasizes the discomfort that the

seethingpopulace could inspire:

The insolence of the crowd is extreme. They swing up onto the back of carriages, and if one of the drivers turns on them with his whip, they jump to the ground and hurl stinking mud at him [...] everything resolves itself with kicks and punches and muddy faces. A perpetual shower of firecrackers rained from the windows onto the seething crowd, popping mischievously under everyone’s clothes and faces and between their legs.

(1266)

If Busino’s image of firecrackers raining onto the crowd is supposed to be festive, it is accompanied

by concern about management and control:

Some men masked as wild giants strode through the crowd with wheels and fireballs, hurling sparks here and there at the bodies and faces of the multitude, but to no avail at making a wide and clear route for the procession.

(1268)

The Pomeranian traveler Lupold von Wedel confirms that policing London’s crowds had long been a problem, noting in his diary that the 1584 Lord Mayor’s Show was preceded by

fire-engines ornamented with garlands, out of which they throw water on the crowd, forcing it to give way, for the streets are quite filled with people(von Wedel 225).

Busino and von Wedel share a wry and even playful tone, but what they are describing is

organized violence.9 London’s governing authorities were willing to turn firecrackers and even early modern water

cannons on the crowds—the same crowds that they had spent vast amounts of money to

attract. Firecrackers and green men became an expected part of the spectacle, an institutionalized

form of crowd control built into the genre itself. Crowds may have been instrumental

to the pomp and legitimacy of the dignitaries honored in an outdoor pageant, but they

were also threatening and unpredictable.

Due in significant part to their distaste for public crowds, Stuart monarchs came

to withdraw support for outdoor pageantry.10 James I gained a reputation for scorning the masses and removing himself from their sight;

as early as his coronation pageant in 1604, the king was understood to be no champion of what Gilbert Dugdale calls the

wylie Multitude(Dugdale sig. B1v). In his account of the The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment of King James, Dugdale acts as something of an apologist for the king, repeatedly emphasizing

the rudenes of the Multitude, who regardles of time [place or] perſon will be ſo troubleſome(Dugdale sig. B2r). Justifying James’s avoidance of the crowds on the basis of their dangerous

pre[ss]ing,Dugdale characterizes them as a

ſtro[n]g ſtream of people violently run[n]ing in the midſt [of the guildmen lining the streets],inclined

with ſuch hurly burly, to run vp and downe with ſuch vnreuerent raſhnes(Dugdale sig. B3v, B1v).

Over the course of the early seventeenth century, monarchal spectacles became increasingly

insular, focusing less on outdoor pageantry and more on the indoor masque. The masque, pioneered by Ben Jonson and Inigo Jones, was a carefully controlled theatrical experience involving the participation of

a learned, courtly audience. Like outdoor pageants, masques were commemorated in printed records that allowed their symbolic agendas to be dispersed

and elucidated far beyond the performance itself. Yet masques were removed from unstable crowds, performed at the Palace of Whitehall, the Inns of Court, and other spaces of privilege. Pageantry, on the contrary, continued to be defined

by the crowds that streamed into the streets, not simply to honor the dignitaries

of the moment but to enjoy a holiday from work and celebrate with other loud and raucous

Londoners.

Noise

As we have seen, pageants were extraordinarily noisy enterprises. The flowery verses

of allegorical personages, the sweet music of instruments and voices, and the yells

and cheers of boisterous crowds competed not only with each other but with London’s everyday sounds, from the cries of street vendors selling their wares to the creaking

of wagon wheels and the neighing of horses. On top of all of this, and epitomizing

the experience of pageantry for many onlookers, were the fireworks and gunfire that

boomed above the Thames and sparkled in the faces of the crowds.

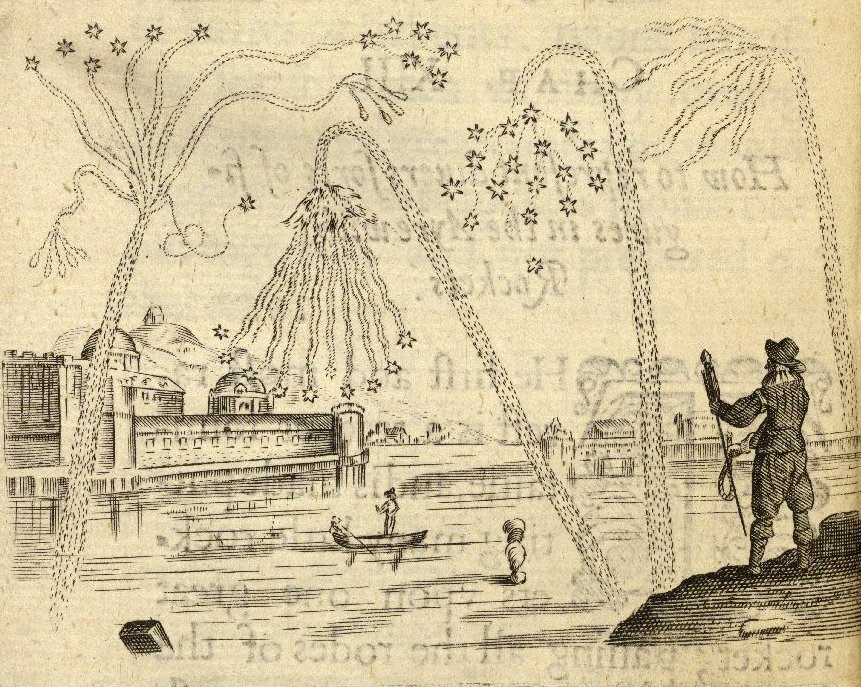

A treatise of artificial fire-vvorks both for vvarres and recreation, 1629.Image courtesy of LUNA at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Pageant designers typically employed greenmen to discharge fireworks and gun salutes,

which were especially prominent during the sea spectacles that preceded the processionals through London. Smaller firecrackers called squibs

were common in the streets as well; we have already seen Busino recount that a

perpetual shower of firecrackers rained from the windowsand

wild giants strode through the crowd with wheels and fireballs(Busino 1266, 1268). Recollections of gunfire are a typical feature of diarists’ accounts of pageants, as in the Russian ambassador Aleksei Ziuzin’s description of Middleton’s The Triumphs of Truth:

And the King’s trumpeters trumpeted, and they beat the drums and they played on litavra [kettle drums] and there were all sorts of various instruments. And they fired a great salute from the ship in which the Lord Mayor sailed and from other ships which were there and from big boats and from the City wall. And from all the small boats there was a great shooting of muskets.

(978)

Fireworks also feature prominently in literary allusions to pageantry, as in William Fennor’s verse satire Cornu-copiae, Pasquils night-cap (1612):

(Fennor sig. H1r)When as the Pageants through Chepe-ſide are carried,What multitudes of people thither ſway,Thruſting ſo hard, that many haue miſcarried.If then you marke when as the fire-workes flye,And Elephants and Vnicornes paſſe by,How mighty and tumultuous is that preſſe.

In both of these examples, fireworks do not stand alone as acoustic events; instead,

they mark a noisy climax in the broader experience of pageantry.

As with music, fireworks also work their way into pageant records, often as allusions

designed to recall the majesty of the pageant day and occasionally as a more elaborate

dimension of a pageant’s allegorical agenda. In Dekker’s 1612 Lord Mayor’s Show Troia-Nova Triumphans, for example, the villainous personage Envy, who is associated with noisy disorder,

incorporates fireworks into the center of the fictional narrative. Seeking to halt

the mayoral procession, Envy instructs her deputies Riot and Calumny to produce an

explosion of infernal noise:

(Dekker sig. B4v)ADders ſhoote, hyſſe ſpeckled Snakes [...]Vomit ſulphure to confound her,Fiendes and Furies (that dwell vnder)Lift hell gates from their hindges: comeYou clouen-foote-broode of Barrathrum,Stop, ſtay her, fright her, with your ſhreekes,And put freſh bloud in Enuies cheekes.

At this point everyone in Envy’s faction chants or shouts

Shoote, Shoote, &c.,and Dekker notes in a stage direction of sorts that these lines coincide with literal fireworks:

(Dekker sig. C1r)Either during this ſpeech, or elſe when it is done, cer-taine Rockets flye vp into the aire; The Throne of Ver-tue paſſing on ſtill, neuer ſtaying, but ſpeaking ſtillthoſe her two laſt lines, albeit, ſhee bee out of thecrying ſtill, ſhoote, ſhoote.

The scene is all the more suggestive because it is impossible to distinguish the sounds

of misrule and disruption from those of celebration. Envy and her

Fort of Furiescontinue to parley with Virtue throughout the pageant, until, finally,

thoſe twelue that ride armed diſcharge their Piſtols, at which Enuy, and the reſt, vaniſh, and are ſeene no more(Dekker sig. C4r)—vanquished by the same disorderly tools with which they are associated.

One implication of Dekker’s emphasis on fireworks in Troia-Nova Triumphans is that his printed record becomes open to its environment, providing a sounding

board for the sensory environs of the pageant day. Something similar happens in the

printed pamphlet for Dekker’s London’s Tempe, where the

concordant stroakesof the smiths’ banging melds with the drumming in and around the pageant floats, and the

Thunder and Lightningdepicted in the fictional Lemnian Forge cannot be distinguished from the fireworks and gunfire set off throughout the Lord Mayor’s Day. By emphasizing the explosive force of rockets, pistols, shrieks, and thunderous banging, Dekker’s pageants draw ambient noise into the core of their symbolic design, incorporating the atmosphere surrounding the text into its allegorical program.

Conclusion

If silence is a process of filtering out what we do not wish not to hear, noise is

what enters our ears nevertheless, unwelcome and uninvited. Theorists including R. Murray Schafer and Jacques Attali define noise as unwanted sound, and the term was sometimes used in this way during

the early modern period as well, as in the

strange, hollow, and confused noisethat disrupts Prospero’s nuptial entertainment in The Tempest (Shakespeare 4.1.138).11 When noise is conceived in this way, the question becomes who wants a particular sound and who does not—Caliban, Trinculo, and Stephano hope to turn

noises, / Sounds and sweet airsto the advantage of their rebellion (Shakespeare 3.2.135-36), and Prospero capitalizes on the noisy confusion of the storm at the outset of the play. What is noise to one character is music to another.

Whether sound is wanted is a matter of perspective, that is, and defining what counts

as noise could be a powerful act in itself. Poets would be wary of sounds that did

not line up with their symbolic goals or that distracted from the exaltation of their

patrons. In Dekker’s London’s Tempe, the

stroakes and soundesof the smiths in are portrayed as

concordant,beautiful music, while in Middleton’s Civitatis Amor, the

over-greedy noiseof the rambunctious crowd is portrayed as an obstacle to the majesty of Prince Charles. Sound could be a tool to bring out the glory of the dignitary being honored, or it could challenge the very subject of a pageant, undermining the propaganda it wished to convey.

Given the pressures involved in describing and defining varying types of noise, many

of the sounds of pageantry would not have been recorded at all. Sounds thought by

the pageant poet to be irrelevant or extraneous, such as the jingling of morris dancers’

bells or the hawking of balladmongers, might not be considered worthy of record. Embarrassing

sounds—the giggling of impertinent onlookers, perhaps—might have been excised from

written records or never have made it to the page in the first place. Quieter sounds

such as the strumming of lutes or the whispering of courtiers might have been heard

by too few people to be likely to survive. Conjuring up the soundscape on pageant day requires extrapolating from the hints that survive: since we know

from livery company account books that sweetmeats were frequently purchased in advance

of pageants, for example, we can assume that, underneath so many louder noises, they

made a crunching sound in the mouths of spectators.

Since we can never know exactly what goes unacknowledged in surviving descriptions

and records, hearing the sounds of pageantry requires imagination. The same could

be said of other historical phenomena; manuscripts, printed books, and other materials

from the past are constantly subject to destruction, forgetfulness, and misunderstanding.

Before the advent of audio recording technologies, however, sound was especially vulnerable

to ephemerality and loss. This makes listening to historical soundscapes a creative act: grounded in detail and attentive to context, but always dependent

upon an open mind and an open ear.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Stanley Plumly for his rendition of the smith’s song, Lauren Friedman

for her help making the audio recording, and the reviewer of this essay for helpful

suggestions.12

Notes

- For overall accounts of London’s outdoor pageantry during the early modern period, see Bergeron, especially his discussion of the stagecraft or

body

of the shows, 238-62; and Manley, 212-93. On Lord Mayor’s Shows, see Hill, especially her analysis of eyewitness accounts of the shows, 118-213. On Elizabethan progresses, see Leahy, especially his discussion of thecommon audience,

53-100. (ST)↑ - The Lord Mayor in 1617 was George Bolles. (JT)↑

- Other authors include Anthony Munday, George Peele, John Webster, and John Taylor. (ST)↑

- Whereas the original costs were 645 pounds, 8 shillings, and 4 pence, the costs for reviving the pageant (which included eight earthen pans and a load of coals to dry the floats) came to 64 pounds, 14 shillings, and 1 penny (Robertson and Gordon 69-70). (ST)↑

- There were four printed accounts of The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment of King James, which vary significantly. The edition cited here provides an ideal reconstruction, rather than an account of what anyone saw or heard on 15 March 1604 (Smuts 219). (ST)↑

- For example, the account books for the Ironmongers, the livery company that commissioned the 1618 Lord Mayor’s Show Sidero-Thriambos, indicate a payment of four pounds

for kettel drum[m]es with 4 trumpeters on horsebacke

(Robertson and Gordon 96). (ST)↑ - On the history of monopolies over music printing in Elizabethan and early Stuart England, see Smith. (ST)↑

- On London’s crowds and their role in civic pageantry, see Munro, 51-74. (ST)↑

- On violence and injury in processional drama, see Northway. (ST)↑

- On the decline of monarchical progresses during the Stuart era, including Charles I’s abrupt withdrawal of support for his coronation entry through London, see Bergeron, 67-68, 76, and 110-12. (ST)↑

- On noise as disruption and even violence, see Schafer, 181-202 and Attali, 26-27. Note that

noise

was an unstable term in the early modern period: as the OED suggests, the term could denotesound of any kind,

including apleasant or melodious sound,

as in Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene:there was an heauenly noise / Heard sownd through all the Pallace pleasantly, / Like as it had bene many an Angels voice

(Spenser I.ii.39). Note also that in communication theory,noise

refers to anything that disrupts or interferes with the transmission of information from sender to receiver. (ST)↑ - MoEML has a blind peer review policy. We ask reviewers if they are willing to have their names listed once the article is published. (JJ)↑

References

-

Citation

Attali, Jacques. Noise: The Political Economy of Music. Translated. Brian Massumi. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1985.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Bergeron, David M. English Civic Pageantry 1558–1642. London: Edward Arnold, 1971.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Busino, Orazio.Orazio Busino’s Eyewitness Account of The Triumphs of Honour and Industry.

Translated. Kate D. Levin. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 1264-70.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Dekker, Thomas. The magnificent entertainment giuen to King James, Queene Anne his wife, and Henry Frederick the Prince, upon the day of his Majesties triumphant passage (from the Tower) through his honourable citie (and chamber) of London, being the 15. of March. 1603. As well by the English as by the strangers: with the speeches and songes, deliuered in the severall pageants. London: Printed by Thomas Creede for Thomas Man the younger, 1604. EEBO. Reprint. Subscription.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Dekker, Thomas, Stephen Harrison, Ben Jonson, and Thomas Middleton. The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment of King James through the City of London, 15 March 1604, with the Arches of Triumph. Ed. R. Malcolm Smuts. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 219-79.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Dugdale, Gilbert. The time triumphant declaring in briefe, the arival of our soveraigne liedge Lord, King James into England, his coronation at Westminster: together with his late royal progresse, from the Towre of London throúgh the Cittie, to his Highnes manor of White Hall. Shewing also, the varieties & rarieties of al the sundry trophies or pageants, erected... With a rehearsall of the King and Queenes late comming to the Exchaunge in London. London, 1604. EEBO. Reprint. Subscription.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Hill, Tracey. Pageantry and Power: A cultural history of the early modern Lord Mayor’s Show 1585–1639. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2013.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Leahy, William. Elizabethan Triumphal Processions. Aldershot, U.K.: Ashgate, 2005.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Manley, Lawrence. Literature and Culture in Early Modern London. Cambridge: Cambridge, UP, 1997.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Marsh, Christopher. Music and Society in Early Modern England. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2010.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Middleton, Thomas. Civitatis Amor. Ed. David Bergeron. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 1202-8.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Munro, Ian. The Figure of the Crowd in Early Modern London: The City and Its Double. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Northway, Kara.

Shakespeare Bulletin. 26.4 (2008): 25-52. Subscription. doi:10.1353/shb.0.0039.[H]urt in that service

: The Norwich Affray and Early Modern Reactions to Injuries during Dramatic Performances.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2012. Subscription. OED.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Robertson, Jean, and D. J. Gordon, eds. Collections, Vol. III: A Calendar of Dramatic Records in the Books of the Livery Companies of London, 1485-1640. Oxford: Malone Society, 1954.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Sayle, R. T. D., ed. Lord Mayors’ Pageants of the Merchant Taylors’ Company in the 15th, 16th & 17th Centuries. London: The Eastern P, Ltd., 1931.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Schafer, R. Murray. The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World. 2nd ed. Rochester, VT: Destiny Books, 1994.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Shakespeare, William. The Tempest. Ed. Brent Whitted and Paul Yachnin. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Smith, Jeremy L. Thomas East and Music Publishing in Renaissance England. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Smuts, R. Malcolm, ed. The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment of King James through the City of London, 15 March 1604, with the Arches of Triumph. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Spenser, Edmund. The Faerie Queene. Ed. A. C. Hamilton, Hiroshi Yamashita, and Toshiyuki Suzuki. Rev. 2nd ed. Harlow, U.K.: Pearson Longman, 2007.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

The Bible: Authorized King James Version with Apocrypha. Ed. Robert Carroll and Stephen Prickett. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

von Wedel, Lupold.Journey Through England and Scotland Made by Lupold von Wedel in the Years 1584 and 1585.

Translated. Gottfried von Bülow. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, New Series. 9 (1895): 223-70. Subsc. doi:10.2307/3678110.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Ziuzin, Aleksei.An Account by Aleksei Ziuzin.

Ed. Maija Jansson and Nikolai Rogozhin. Translated. Paul Bushkovitch. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 977-79.This item is cited in the following documents:

Cite this page

MLA citation

.

The Sounds of Pageantry.The Map of Early Modern London, edited by , U of Victoria, 20 Jun. 2018, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/SOUN1.htm.

Chicago citation

.

The Sounds of Pageantry.The Map of Early Modern London. Ed. . Victoria: University of Victoria. Accessed June 20, 2018. http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/SOUN1.htm.

APA citation

2018. The Sounds of Pageantry. In (Ed), The Map of Early Modern London. Victoria: University of Victoria. Retrieved from http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/SOUN1.htm.

RIS file (for RefMan, EndNote etc.)

Provider: University of Victoria Database: The Map of Early Modern London Content: text/plain; charset="utf-8" TY - ELEC A1 - Trudell, Scott ED - Jenstad, Janelle T1 - The Sounds of Pageantry T2 - The Map of Early Modern London PY - 2018 DA - 2018/06/20 CY - Victoria PB - University of Victoria LA - English UR - http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/SOUN1.htm UR - http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/xml/standalone/SOUN1.xml ER -

RefWorks

RT Web Page SR Electronic(1) A1 Trudell, Scott A6 Jenstad, Janelle T1 The Sounds of Pageantry T2 The Map of Early Modern London WP 2018 FD 2018/06/20 RD 2018/06/20 PP Victoria PB University of Victoria LA English OL English LK http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/SOUN1.htm

TEI citation

<bibl type="mla"><author><name ref="#TRUD1"><surname>Trudell</surname>, <forename>Scott</forename></name></author>. <title level="a">The Sounds of Pageantry</title>. <title level="m">The Map of Early Modern London</title>, edited by <editor><name ref="#JENS1"><forename>Janelle</forename> <surname>Jenstad</surname></name></editor>, <publisher>U of Victoria</publisher>, <date when="2018-06-20">20 Jun. 2018</date>, <ref target="http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/SOUN1.htm">mapoflondon.uvic.ca/SOUN1.htm</ref>.</bibl>Personography

-

Janelle Jenstad

JJ

Janelle Jenstad, associate professor in the department of English at the University of Victoria, is the general editor and coordinator of The Map of Early Modern London. She is also the assistant coordinating editor of Internet Shakespeare Editions. She has taught at Queen’s University, the Summer Academy at the Stratford Festival, the University of Windsor, and the University of Victoria. Her articles have appeared in the Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Early Modern Literary Studies, Elizabethan Theatre, Shakespeare Bulletin: A Journal of Performance Criticism, and The Silver Society Journal. Her book chapters have appeared (or will appear) in Performing Maternity in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2007), Approaches to Teaching Othello (Modern Language Association, 2005), Shakespeare, Language and the Stage, The Fifth Wall: Approaches to Shakespeare from Criticism, Performance and Theatre Studies (Arden/Thomson Learning, 2005), Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society (Brill, 2004), New Directions in the Geohumanities: Art, Text, and History at the Edge of Place (Routledge, 2011), and Teaching Early Modern English Literature from the Archives (MLA, forthcoming). She is currently working on an edition of The Merchant of Venice for ISE and Broadview P. She lectures regularly on London studies, digital humanities, and on Shakespeare in performance.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Stub

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

Author of Textual Introduction

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Course Instructor

-

Course Supervisor

-

Course supervisor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Structure and Toponyms)

-

Final Markup Editor

-

GIS Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Modern)

-

Geographical Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Main Transcriber

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Name Encoder

-

Peer Reviewer

-

Primary Author

-

Project Director

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Reviser

-

Second Author

-

Second Encoder

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Janelle Jenstad is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Janelle Jenstad is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Tye Landels-Gruenewald

TLG

Research assistant, 2013-15, and data manager, 2015 to present. Tye completed his undergraduate honours degree in English at the University of Victoria in 2015.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

MoEML Researcher

-

Name Encoder

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

Contributions by this author

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kim McLean-Fiander

KMF

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach, 2015–present; Associate Project Director, 2015–present; Assistant Project Director, 2013-2014; MoEML Research Fellow, 2013. Kim McLean-Fiander comes to The Map of Early Modern London from the Cultures of Knowledge digital humanities project at the University of Oxford, where she was the editor of Early Modern Letters Online, an open-access union catalogue and editorial interface for correspondence from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. She is currently Co-Director of a sister project to EMLO called Women’s Early Modern Letters Online (WEMLO). In the past, she held an internship with the curator of manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library, completed a doctorate at Oxford on paratext and early modern women writers, and worked a number of years for the Bodleian Libraries and as a freelance editor. She has a passion for rare books and manuscripts as social and material artifacts, and is interested in the development of digital resources that will improve access to these materials while ensuring their ongoing preservation and conservation. An avid traveler, Kim has always loved both London and maps, and so is particularly delighted to be able to bring her early modern scholarly expertise to bear on the MoEML project.Roles played in the project

-

Associate Project Director

-

Author

-

Author of MoEML Introduction

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Contributor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Contributor

-

Data Manager

-

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (People)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Managing Editor

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Research Fellow

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Second Author

-

Secondary Author

-

Secondary Editor

-

Toponymist

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Kim McLean-Fiander is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Kim McLean-Fiander is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Joey Takeda

JT

Programmer, 2018-present; Junior Programmer, 2015 to 2017; Research Assistant, 2014 to 2017. Joey Takeda is an MA student at the University of British Columbia in the Department of English (Science and Technology research stream). He completed his BA honours in English (with a minor in Women’s Studies) at the University of Victoria in 2016. His primary research interests include diasporic and indigenous Canadian and American literature, critical theory, cultural studies, and the digital humanities.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Stub

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Date Encoder

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Bibliography)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Agas)

-

Junior Programmer

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Encoder

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Second Author

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Editor

Contributions by this author

Joey Takeda is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Joey Takeda is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Scott Trudell

ST

Scott A. Trudell is Assistant Professor of English at the University of Maryland, College Park, where his research and teaching focus on early modern literature, media theory and music. In addition to his current book project about song and mediation from Sidney and Shakespeare to Jonson and Milton, he has research interests in gender studies, digital humanities, pageantry and itinerant theatricality. His work has been published in Shakespeare Quarterly, Studies in Philology and edited collections. See Trudell’s profile at the University of Maryland and his professional website.Roles played in the project

-

Author

Contributions by this author

Scott Trudell is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Tracey Hill

Dr. Tracey Hill is head of the department of English and Cultural Studies at Bath Spa University. Her specialism is in the literature and history of early modern London. She is the author of two books: Anthony Munday and Civic Culture (Manchester UP, 2004), and Pageantry and Power: A Cultural History of the Early Modern lord mayor’s Shows, 1585–1639 (Manchester UP, 2010). She has also published a number of articles on Munday’s prose works, on The Booke of Sir Thomas More, and on late Elizabethan history plays.Roles played in the project

-

Guest Editor

-

Peer Reviewer

Tracey Hill is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Tracey Hill is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Martin D. Holmes

MDH

Programmer at the University of Victoria Humanities Computing and Media Centre (HCMC). Martin ported the MOL project from its original PHP incarnation to a pure eXist database implementation in the fall of 2011. Since then, he has been lead programmer on the project and has also been responsible for maintaining the project schemas. He was a co-applicant on MoEML’s 2012 SSHRC Insight Grant.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of abstract

-

Conceptor

-

Encoder

-

Name Encoder

-

Post-conversion and Markup Editor

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

Contributions by this author

Martin D. Holmes is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Martin D. Holmes is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

George Bolles is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Brute is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Orazio (Horatio) Busino is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Charles I

Charles Stuart I King of England, Scotland, and Ireland

(b. 1600, d. 1649)King of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Charles II

Charles II King of England, Scotland, and Ireland

(b. 1630, d. 1685)King of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Geoffrey Chaucer is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thomas Dekker is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Gilbert Dugdale

(fl. 1604)Eyewitness of James I’s 1604 procession into London, as documented in his first-hand account, The Time Triumphant.Gilbert Dugdale is mentioned in the following documents:

-

William Fennor is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Neptune is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Envy

Personification of envy. Appears as an allegorical character in mayoral shows.Envy is mentioned in the following documents:

-

George Gascoigne is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thomas Heywood is mentioned in the following documents:

-

James VI and I

King James Stuart VI and I

(b. 1566, d. 1625)King of Scotland, England, and Ireland.James VI and I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Inigo Jones is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Ben Jonson is mentioned in the following documents:

-

London

Allegorical character representing the city of London. See also the allegorical character representing Roman London, Troya-Nova.London is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thomas Middleton is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thomas Morley

(b. 1556, d. in or after 1602)Composer renowned for his work on the English madrigal. Not to be confused with Thomas Morley, who is buried in Austin Friars, or Thomas Morley, buried in All Hallows Barking.Thomas Morley is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Anthony Munday

(bap. 1560, d. 1633)Playwright, actor, pageant poet, translator, and writer. Possible member of the Draper’s Company and/or the Merchant Taylor’s Company.Anthony Munday is mentioned in the following documents:

-

George Peele is mentioned in the following documents:

-

William Shakespeare is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Squire is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Taylor is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Webster is mentioned in the following documents:

-

London’s Genius

Personification of London’s genius. Appears as an allegorical character in mayoral shows.London’s Genius is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Sir Philip Sidney is mentioned in the following documents:

Locations

-

The Thames is mentioned in the following documents:

-

St. Paul’s Churchyard is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Cheapside Street

Cheapside, one of the most important streets in early modern London, ran east-west between the Great Conduit at the foot of Old Jewry to the Little Conduit by St. Paul’s churchyard. The terminus of all the northbound streets from the river, the broad expanse of Cheapside separated the northern wards from the southern wards. It was lined with buildings three, four, and even five stories tall, whose shopfronts were open to the light and set out with attractive displays of luxury commodities (Weinreb and Hibbert 148). Cheapside was the centre of London’s wealth, with many mercers’ and goldsmiths’ shops located there. It was also the most sacred stretch of the processional route, being traced both by the linear east-west route of a royal entry and by the circular route of the annual mayoral procession.Cheapside Street is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Guildhall is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Tower of London is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Temple Bar

Temple Bar was one of the principle entrances to the city of London, dividing the Strand to the west and Fleet Street to the east. It was an ancient right of way and toll gate. Walter Thornbury dates the wooden gate structure shown in the Agas Map to the early Tudor period, and describes a number of historical pageants that processed through it, including the funeral procession of Henry V, and it was the scene of King James I’s first entry to the city (Thornbury 1878). The wooden structure was demolished in 1670 and a stone gate built in its place (Sugden 505).Temple Bar is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Westminster is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Whitehall is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Little Conduit (Cheapside)

The Little Conduit in Cheapside, also known as the Pissing Conduit, stood at the western end of Cheapside outside the north corner of Paul’s Churchyard. On the Agas map, one can see two water cans on the ground just to the right of the conduit.Little Conduit (Cheapside) is mentioned in the following documents:

-

The Inns of Court

The four principal constituents of the Inns of Court were:The Inns of Court is mentioned in the following documents:

Organizations

-

The Fishmongers’ Company

The Worshipful Company of Fishmongers

The Fishmongers’ Company was one of the twelve great companies of London. The Fishmongers were fourth in the order of precedence established in 1515. The Company was originally two companies, the Stock-fishmongers and the Salt-fishmongers (or simply Fishmongers). They were united in 1536 under the designation ofThe Wardens and Commonalty of the Mystery of Fishmongers of the City of London

(Herbert 4) The Worshipful Company of Fishmongers is still active and maintains a website at http://www.fishhall.org.uk/, including a section on their history and heritage.![The coat of arms of the Fishmongers’ Company, from Stow (1633). [Full size image]](graphics/Fishmongers_sm.jpg)

The coat of arms of the Fishmongers’ Company, from Stow (1633). [Full size image] This organization is mentioned in the following documents:

-

The Merchant Taylors’ Company

The Worshipful Company of Merchant Taylors

The Merchant Taylors’ Company was one of the twelve great companies of London. Since 1484, the Merchant Taylors and the Skinners have alternated precedence annually; the Merchant Taylors are now sixth in precedence in odd years and seventh in even years, changing precedence at Easter. The Worshipful Company of Merchant Taylors is still active and maintains a website at http://www.merchanttaylors.co.uk/ that includes downloadable information about the origins and historical milestones of the company.![The coat of arms of the Merchant Taylors’ Company, from Stow (1633). [Full size image]](graphics/MerchantTaylors_sm.jpg)

The coat of arms of the Merchant Taylors’ Company, from Stow (1633). [Full size image] This organization is mentioned in the following documents:

-

The Haberdashers’ Company

The Worshipful Company of Haberdashers

The Haberdashers’ Company was one of the twelve great companies of London. The Haberdashers were eighth in the order of precedence established in 1515. The Worshipful Company of Haberdashers is still active and maintains a website at http://www.haberdashers.co.uk/ that includes a history of the company and of their hall.![The coat of arms of the Haberdashers’ Company, from Stow (1633). [Full size image]](graphics/Haberdashers_sm.jpg)

The coat of arms of the Haberdashers’ Company, from Stow (1633). [Full size image] This organization is mentioned in the following documents:

-

The Ironmongers’ Company

The Worshipful Company of Ironmongers

The Ironmongers’ Company was one of the twelve great companies of London. The Ironmongers were tenth in the order of precedence established in 1515. The Worshipful Company of Ironmongers is still active and maintains a website at http://www.ironmongers.org/ that includes a page on their history.![The coat of arms of the Ironmongers’ Company, from Stow (1633). [Full size image]](graphics/Ironmongers_sm.jpg)

The coat of arms of the Ironmongers’ Company, from Stow (1633). [Full size image] This organization is mentioned in the following documents: