London Bridge

This document is currently in draft. When it has been reviewed and proofed, it will

be

published on the site.

Please note that it is not of publishable quality yet.

London Bridge

A Brief History

From the time the first wooden bridge in London was built by the Romans in 52 CE until 1729 when Putney Bridge opened, London Bridge was the only bridge across the Thames in London. During this time, several structures were built upon the bridge, though

many were either dismantled or fell apart. John Stow’s 1598 A Survey of London claims that the contemporary version of the bridge was already outdated by 994, likely due to the bridge’s wooden construction (Stow 1:21).

Stow’s first record of a fire burning down the wooden bridge is in 1136 (Stow 1:22). We have record of a wooden bridge in the same place for two hundred

and fifteen years, before a bridge of stone was begun in 1176 (Stow 1:23).

Because London Bridge was the only way to cross the Thames without a boat and the wooden bridges of the past were rickety and sometimes unsafe,

the construction of the stone bridge was important to the city of London. In 1176, the new stone bridge was begun slightly to the west of the wooden bridge to allow

construction of the new bridge while the old bridge was still in use (Stow 1:23). Commissioned by King Henry II, partially funded by Richard of Dover, Archbishop of Canterbury and designed by Peter of Colechurch, the stone bridge was

20 feet wide and 300 yards long and was supported by 20 arches curving to a point in Gothic Style(The Peter De Colechurch Bridge; Stow 1:23). The arches were 60 feet tall and 20 feet

distant from one another(Stow 1:26). This process of construction was not a short one. The construction of the bridge in its early-modern state was begun in 1176 under King Henry II, and finished under King John I, and the designer of the bridge, Peter of Colechurch died during the thirty-three year construction and was buried in the Chapel of Saint Thomas Becket on the bridge. The project was finished in 1209 (Stow 1:23).

New Construction

While most modern bridges provide only crossing for traffic of one kind or another,

buildings were built upon London Bridge in attempt to help repay the enormous cost of the construction (Stow 23). The first building built on the bridge was a , built on the east side of the bridge and south side of the river (Stow 23-4). The bridge in this iteration lasted for over six hundred years (although it needed

serious repair several times), and

it had gatehouses, a drawbridge and… street houses to provide rent for the upkeep of the bridge”(The Peter De Colechurch Bridge). By 1358, the bridge had already been covered with 138 shops, which sold various goods to those crossing the bridge. The number of shops adorning the bridge consistently grew over time, at one point pre-Great Fire reaching a number of 200, several with up to seven stories, and many that would hang over the river by measures of feet. These shops would not be permanent owners of their space on the bridge but rather would rent their places at various rates. has data for Bridge House rentals from 1381-1538 available through the British History Online project, accessible here. For example, rent in 1401 varied from four pounds to eight pounds yearly, with a total income for the year totaling approximately 500 pounds for all rentals. he cost of the construction was astronomical, as instead of being constructed of wood like its earlier iterations, this version was made of stone. In what would prove to be an unsuccessful attempt to offset the cost of construction, King Henry II placed a tax upon both wool and sheepskin, and King John licensed building plots. Neither of these tactics fully recouped the cost of construction, and in 1284 the City of London acquired the charter of maintenance for the bridge through loaning money to the royal purse in attempt to further recover the cost of construction.

The Colechurch bridge, while proving to be quite resilient, did have its issues: namely, fire. Fire was

a consistent issue for the earlier wooden bridge, but fire was not a problem solved

by its newer stone construction. On July 10, 1212, a fire started in Our Lady of the Canons Church on the south side of the Thames. Strong winds whipped sparks to the north end of the bridge, leaving the people on

the bridge stranded between the fires (Stow 24). Boats came to the bridge for a rescue attempt; but tragically, so many jumped on

each boat that every boat sank, bringing the death toll to around three thousand (Stow 24). Additionally, in response and in an attempt to help fund restoration of the bridge

after the 1212 fire, King John placed tolls levied onto foreign merchants toward the funding of these repairs. To

further fund repairs, King Henry III permitted certain monks to travel the country to collect alms to be dedicated specifically

to the bridge repair fund. These monks were exclusively members of the . In addition to the collection of alms by the Brethren of the London Bridge, a toll

was charged to those crossing the bridge. The costs assigned to cross the bridge,

informing us that in the year 1281 a crossing cost

every man on foot, with merchandise, to pay one farthing; every horseman, one penny; every pack carried on horseback, one halfpenny(Thornbury 1: 9). These tolls, while a reasonable rate, were doubtlessly an important component in the recuperation of the money spent on the bridge’s construction considering the number of citizens crossing the bridge each year.

In addition to destructive fires, the Bridge saw other destructive conflicts. Due

to the fact that the bridge was the sole manner for an infantry-based army to cross

the Thames, London Bridge was the site of many battles. In 1450, Jack Cade attempted to take the city of London, but the residents of the bridge overcame him

and his followers (Stow 25). In 1471,1481, and 1553 other battles and sieges were conducted on London Bridge, but because of the on both ends of the bridge, none of the potential invasions were successful in taking

London (Stow 25-6).

The bridge was also the site of celebration and ceremony. Thornbury also writes of

the return of King Richard II in 1392, stating:

In 1392, when Richard II returned to London, reconciled to the citizens, who had resented his reckless extravagance, London Bridge was the centre of splendid pageants. At the bridge-gate the citizens presented the handsome young scapegrace with a milk-white charger, caparisoned in cloth of gold and hung with silver bells, and gave the queen a white palfrey, caparisoned in white and red; while from every window hung cloths of gold and silver. The citizens ended by redeeming their forfeited charter by the outrageous payment of £10,000(Thornbury 12). This event serves to highlight just how important London Bridge was to the culture of Early Modern London in addition to its importance as a river crossing. By adorning the bridge so extravagantly to celebrate the return of the King, the city displayed the importance of the bridge as a culture and physical crossing.

Shooting the Bridge

The Colechurch Bridge had some deficiencies, the largest of which was its negative effect on the navigability

of the Thames. Because the Thames is a tidal river, the current changes direction with the tides. The arches across

the river were not equidistant, and this caused the river to develop spots that were

not only difficult but in some places dangerous to navigate when going under the bridge.

The bargemen who worked the river had their favorite spots to cross depending on the

tidal level. They called it

shooting the bridgein the same way that people today shoot rapids.

The dangers of shooting London Bridge were exemplified as early as 1428 (in the same reign—Henry VI):

The barge of the Duke of Norfolk, starting from St. Mary Overie’s, with many a gentleman, squire, and yeoman, about half-past four of the clock on a November afternoon, struck (through bad steering) on a starling of London Bridge, and sank(Thornbury 13). The duke and two or three other gentlemen fortunately leaped on the piles were saved by ropes cast down from the parapet above; the rest, however, perished.

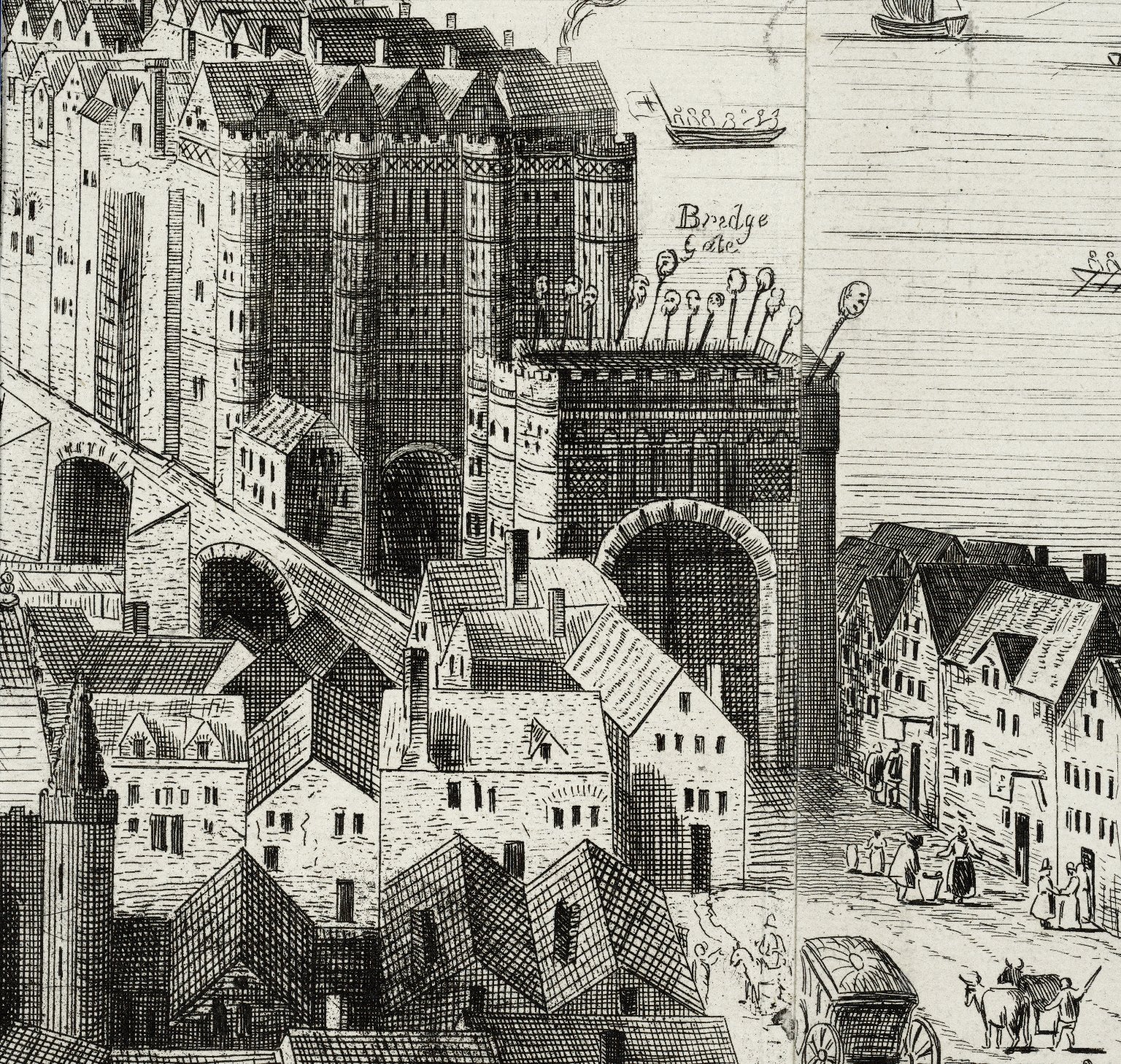

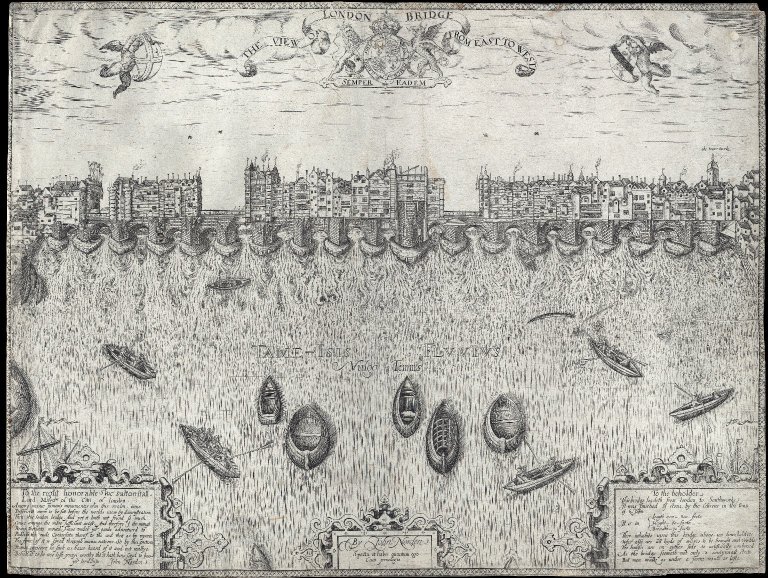

Upon close inspection of John Norden’s illustration, it is possible to see the currents that surround the arches that

support the bridge. These currents are what necessitated the act of

shooting the bridge.It is also possible to see small boats about to

shoot the bridge.

London Bridge Experience

Crossing London Bridge during the early modern period was unlike crossing any bridge that we have today.

The majority of the twenty-foot wide bridge was taken up with structures on either

side. Because London Bridge was the only way to cross the Thames that did not involve a boat, it was the primary way that carriages, wagons, and horses

crossed the river, making traffic both thick and dangerous. Since there were no sidewalks

on the bridge, pedestrians needed to be at least as aware of other traffic as they

were in the narrow, winding roads of London. The structures on either side were so

large that they needed to be buttressed from the river below and had to be connected

across the bridge with wood for support; otherwise, they would either fall into the

river or crash down on the bridge. The structures

above the shops…leaned so far over the street that Mistress A could pass a sausage to Mistress B across the road without leaving her house(Cushman 128). While not connecting the structures in such a way as to provide protection from the rain or snow, this connection must have given the bridge a claustrophobic feeling. In addition to the traffic and narrowness of the bridge, in 1304 London began putting traitors’ heads on poles attached to the gate house. The first person with this ignoble

honorwas William Wallace. The practice of displaying heads on London bridge (as depicted in Claes Visscher’s illustration, shown above), seems to have continued for centuries. Perhpas most notably, the head of Sir Thomas More was displayed on the bridge in 1535, following which Thomas Cromwell’s head was displayed following his execution in 1540. James Shapiro notes that Shakespeare’s relative, John Somerville, along with Edward Arden, had their heads

mounted on stakes atop London Bridge(Shapiro 142) as punishment for their involvement in Catholic conspiracy against Queen Elizabeth I’s life in 1583. The displaying of heads on the bridge functions as a symbolic testament to political authority. In terms of early modern theatrical culture, many playgoers would have had to cross the London Bridge to reach The Swan, The Globe, and The Rose in Southwark, perhaps adding additional dimensions of significance to a plays staged in their respective theatrical venunes, especially those dealing with execution and treason.

While the bridge was generally a place of business, residence, and a way to cross

the Thames, it was also a site for spectacle, rebellion, and fire. In 1390, there was a joust on the bridge pertaining to the honor of the Scottish people.

In 1471 Thomas Neville (the Bastard of Faulconbridge) burned down thirteen houses on the bridge. In 1481, one of the houses fell into the Thames, drowning five men. Given the traffic on the bridge and the number of people who

lived on it, this is a surprisingly low number.

During the Great Fire of London in 1666, the bridge was one of the few places in the heart of London not completely decimated.

Because of an earlier fire that occurred in 1633, most of the houses on the bridge were spared. The fire had left a large break between

buildings that had not been completely rebuilt by the time of the great fire, which meant that while forty-three houses burned down, the rest of the bridge remained

sound. Had the gap from the previous fire not happened, all of the structures on the

bridge would have caught fire, and there is a very real possibility that the fire

could have crossed into South London.

Over the years, citizen traffic increased on the bridge, and as traffic increased,

the bridge became considerably more dangerous. In 1722, a

keep leftrule was instituted to help with congestion. By 1763, it could take several hours to cross London Bridge, and in order to relieve this congestion, the houses and shops that lined the bridge were torn down, allowing traffic to use the entire twenty feet, changing the experience of crossing the bridge. Due to age, modification, and damage from ice, a new London Bridge was commissioned in 1821, and building was begun on June 15, 1825 (The Rennie Bridge). The most recent incarnation of London Bridge was begun in 1967 with an act of Parliament and officially opened by Queen Elizabeth II in 1973 (2000 Years of London Bridge).

References

-

Citation

2000 Years of London Bridge: From the Arrival of the Romans to the Present Day.

The London Bridge Museum and Education Trust, 2003. Open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

British History Online. Ed. Institute of Historical Research. Open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Catherine, Called Birdy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 1994.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Shapiro, James. 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare. New York: Harper Collins, 2005.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Stow, John. A Survey of London. Reprinted from the Text of 1603. Ed. Charles Lethbridge Kingsford. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1908. [Also available as a reprint from Elibron Classics (2001). Articles written before 2011 cite from the print edition by volume and page number.]This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

The Peter De Colechurch Bridge: Early Mediaeval.

The London Bridge Museum and Educational Trust, 2003. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Thornbury, Walter. Old and New London. 6 vols. London, 1878. Reprint. British History Online. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

Cite this page

MLA citation

London Bridge.The Map of Early Modern London, edited by , U of Victoria, 20 Jun. 2018, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/LOND1.htm.

Chicago citation

London Bridge.The Map of Early Modern London. Ed. . Victoria: University of Victoria. Accessed June 20, 2018. http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/LOND1.htm.

APA citation

2018. London Bridge. In (Ed), The Map of Early Modern London. Victoria: University of Victoria. Retrieved from http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/LOND1.htm.

RIS file (for RefMan, EndNote etc.)

Provider: University of Victoria Database: The Map of Early Modern London Content: text/plain; charset="utf-8" TY - ELEC ED - Jenstad, Janelle T1 - London Bridge T2 - The Map of Early Modern London PY - 2018 DA - 2018/06/20 CY - Victoria PB - University of Victoria LA - English UR - http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/LOND1.htm UR - http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/xml/standalone/LOND1.xml ER -

RefWorks

RT Web Page SR Electronic(1) A6 Jenstad, Janelle T1 London Bridge T2 The Map of Early Modern London WP 2018 FD 2018/06/20 RD 2018/06/20 PP Victoria PB University of Victoria LA English OL English LK http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/LOND1.htm

TEI citation

<bibl type="mla"> <title level="a">London Bridge</title>. <title level="m">The Map of Early Modern London</title>, edited by <editor><name ref="#JENS1"><forename>Janelle</forename> <surname>Jenstad</surname></name></editor>, <publisher>U of Victoria</publisher>, <date when="2018-06-20">20 Jun. 2018</date>, <ref target="http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/LOND1.htm">mapoflondon.uvic.ca/LOND1.htm</ref>.</bibl>Personography

-

Janelle Jenstad

JJ

Janelle Jenstad, associate professor in the department of English at the University of Victoria, is the general editor and coordinator of The Map of Early Modern London. She is also the assistant coordinating editor of Internet Shakespeare Editions. She has taught at Queen’s University, the Summer Academy at the Stratford Festival, the University of Windsor, and the University of Victoria. Her articles have appeared in the Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Early Modern Literary Studies, Elizabethan Theatre, Shakespeare Bulletin: A Journal of Performance Criticism, and The Silver Society Journal. Her book chapters have appeared (or will appear) in Performing Maternity in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2007), Approaches to Teaching Othello (Modern Language Association, 2005), Shakespeare, Language and the Stage, The Fifth Wall: Approaches to Shakespeare from Criticism, Performance and Theatre Studies (Arden/Thomson Learning, 2005), Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society (Brill, 2004), New Directions in the Geohumanities: Art, Text, and History at the Edge of Place (Routledge, 2011), and Teaching Early Modern English Literature from the Archives (MLA, forthcoming). She is currently working on an edition of The Merchant of Venice for ISE and Broadview P. She lectures regularly on London studies, digital humanities, and on Shakespeare in performance.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Stub

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

Author of Textual Introduction

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Course Instructor

-

Course Supervisor

-

Course supervisor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Structure and Toponyms)

-

Final Markup Editor

-

GIS Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Modern)

-

Geographical Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Main Transcriber

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Name Encoder

-

Peer Reviewer

-

Primary Author

-

Project Director

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Reviser

-

Second Author

-

Second Encoder

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Janelle Jenstad is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Janelle Jenstad is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Tye Landels-Gruenewald

TLG

Research assistant, 2013-15, and data manager, 2015 to present. Tye completed his undergraduate honours degree in English at the University of Victoria in 2015.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

MoEML Researcher

-

Name Encoder

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

Contributions by this author

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kim McLean-Fiander

KMF

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach, 2015–present; Associate Project Director, 2015–present; Assistant Project Director, 2013-2014; MoEML Research Fellow, 2013. Kim McLean-Fiander comes to The Map of Early Modern London from the Cultures of Knowledge digital humanities project at the University of Oxford, where she was the editor of Early Modern Letters Online, an open-access union catalogue and editorial interface for correspondence from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. She is currently Co-Director of a sister project to EMLO called Women’s Early Modern Letters Online (WEMLO). In the past, she held an internship with the curator of manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library, completed a doctorate at Oxford on paratext and early modern women writers, and worked a number of years for the Bodleian Libraries and as a freelance editor. She has a passion for rare books and manuscripts as social and material artifacts, and is interested in the development of digital resources that will improve access to these materials while ensuring their ongoing preservation and conservation. An avid traveler, Kim has always loved both London and maps, and so is particularly delighted to be able to bring her early modern scholarly expertise to bear on the MoEML project.Roles played in the project

-

Associate Project Director

-

Author

-

Author of MoEML Introduction

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Contributor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Contributor

-

Data Manager

-

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (People)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Managing Editor

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Research Fellow

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Second Author

-

Secondary Author

-

Secondary Editor

-

Toponymist

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Kim McLean-Fiander is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Kim McLean-Fiander is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Joey Takeda

JT

Programmer, 2018-present; Junior Programmer, 2015 to 2017; Research Assistant, 2014 to 2017. Joey Takeda is an MA student at the University of British Columbia in the Department of English (Science and Technology research stream). He completed his BA honours in English (with a minor in Women’s Studies) at the University of Victoria in 2016. His primary research interests include diasporic and indigenous Canadian and American literature, critical theory, cultural studies, and the digital humanities.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Stub

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Date Encoder

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Bibliography)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Agas)

-

Junior Programmer

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Encoder

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Second Author

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Editor

Contributions by this author

Joey Takeda is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Joey Takeda is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Chase Templet

CT

Research Assistant, 2017. Chase Templet is a graduate student at the University of Victoria in the Medieval and Early Modern Studies (MEMS) stream. He is specifically focused on early modern repertory studies and non-Shakespearean early modern drama, particularly the works of Thomas Middleton.Roles played in the project

-

Compiler

-

Encoder

-

Researcher

Chase Templet is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Martin D. Holmes

MDH

Programmer at the University of Victoria Humanities Computing and Media Centre (HCMC). Martin ported the MOL project from its original PHP incarnation to a pure eXist database implementation in the fall of 2011. Since then, he has been lead programmer on the project and has also been responsible for maintaining the project schemas. He was a co-applicant on MoEML’s 2012 SSHRC Insight Grant.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of abstract

-

Conceptor

-

Encoder

-

Name Encoder

-

Post-conversion and Markup Editor

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

Contributions by this author

Martin D. Holmes is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Martin D. Holmes is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Jack Cade is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thomas Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell Earl of Essex

(b. in or before 1485, d. 1540)Royal minister of Henry VIII.Thomas Cromwell is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth Tudor I Queen of England and Ireland

(b. 7 September 1533, d. 24 March 1603)Queen of England and Ireland.Elizabeth I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Henry II is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Sir Thomas More is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Norden is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Richard II

King Richard II

(b. 6 January 1367, d. 1400)King of England and lord of Ireland, and duke of Aquitaine. Son of Edward, the Black Prince.Richard II is mentioned in the following documents:

-

William Shakespeare is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Stow is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Claes van Visscher

Cartographer. Drew a map of London in 1616.Claes van Visscher is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Anne of Bohemia is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Richard of Dover

Richard of Dover Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury from 1174—1184 CE.Richard of Dover is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Peter of Colechurch

Peter of Colechurch Peter de Colechurch

(d. 1205)Priest of the London parish of St. Mary Colechurch. Organizer of the rebuilding of London Bridge.Peter of Colechurch is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thomas Neville

Thomas Neville Thomas Fauconberg Thomas the Bastard Bastard of Fauconberg

Notable sailor who received the freedom from the City of London in 1454 CE to eliminate pirates from the Channel and the North Sea. Not to be confused with the fifth baron of Furnivall, Thomas Neville.Thomas Neville is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John de Mowbray is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Sir William Wallace

William Sir William

(d. 1305)Scotish knight, patriot, and key figure in the Wars of Scotish Independance.Sir William Wallace is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Edward Arden

(b. 1533, d. 1583)Second cousin of Mary Arden, William Shakespeare’s mother. Catholic executed for conspiracy against Elizabeth I.Edward Arden is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Somerville

(b. 1560, d. 1583)Son-in-law of Edward Arden. Catholic executed for conspiracy against Elizabeth I.John Somerville is mentioned in the following documents:

Locations

-

The Thames is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Chapel of St. Thomas on the Bridge is mentioned in the following documents:

-

St. Mary Overie (Southwark Cathedral)

For information about St. Marie Overie (now known as Southwark Cathedral), a modern map marking the site where the it once stood, and a walking tour that will take you to the site, visit the Shakespearean London Theatres (ShaLT) article on St. Marie Overie.St. Mary Overie (Southwark Cathedral) is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Great Stone Gate is mentioned in the following documents:

-

The Swan

The Swan was the second of the Bankside theatres. It was located at Paris Garden. It was in use from 1595 and possibly staged some of the plays of William Shakespeare

(SHaLT).The Swan is mentioned in the following documents:

-

The Globe is mentioned in the following documents:

-

The Rose

Built in 1587 by theatre financier Philip Henslowe, the Rose was Bankside’s first open-air amphitheatre playhouse (Egan). Its foundation, excavated in 1989, reveals a fourteen-sided structure about 22 metres in diameter, making it smaller than other contemporary playhouses (White 302). Relatively free of civic interference and surrounded by pleasure-seeking crowds, the Rose did very well, staging works by such playwrights as Shakespeare, Marlowe, Kyd, and Dekker (Egan).The Rose is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Southwark is mentioned in the following documents:

Mentions of this place in Internet Shakespeare Editions texts

- Iacke Cade hath gotten London-bridge. (Henry VI, Part 2 (Folio 1, 1623))

- For they haue wonne the Bridge, (Henry VI, Part 2 (Folio 1, 1623))

- But first, go and set London Bridge on fire, (Henry VI, Part 2 (Folio 1, 1623))

Variant spellings

-

Documents using the spelling

Bridg

-

Documents using the spelling

Bridge

-

Documents using the spelling

bridge

-

Documents using the spelling

Colechurch bridge

-

Documents using the spelling

Colechurch Bridge

-

Documents using the spelling

London

-

Documents using the spelling

London bridg

-

Documents using the spelling

London Bridg

-

Documents using the spelling

London bridge

-

Documents using the spelling

London Bridge

- A Survey of London

- Blocks of XML for broad XInclusion in other files, or for reference using the mol: private URI scheme.

- Complete Personography

- Cross-Index for Pantzer Locations

- Excerpts from The Staple of News

- Excerpts from Eastward Ho!

- Excerpts from Epicene, or the Silent Woman

- The Carriers’ Cosmography

- The Doleful Lamentation of Cheapside Cross

- Botolph’s Wharf

- New Fish Street

- Bridge Within Ward

- The Steelyard

- St. Magnus

- Cripplegate

- Andro Morris Key

- London Stone

- Pudding Lane

- The Wall

- Cardinal’s Hat (Southwark)

- Gracechurch Street

- The Elephant

- Charterhouse

- Bridge Without Ward

- Bishopsgate Street

- London Bridge

- Billingsgate

-

Documents using the spelling

Londō bridge