The Steelyard

This document is currently in draft. When it has been reviewed and proofed, it will

be

published on the site.

Please note that it is not of publishable quality yet.

The Steelyard

Introduction

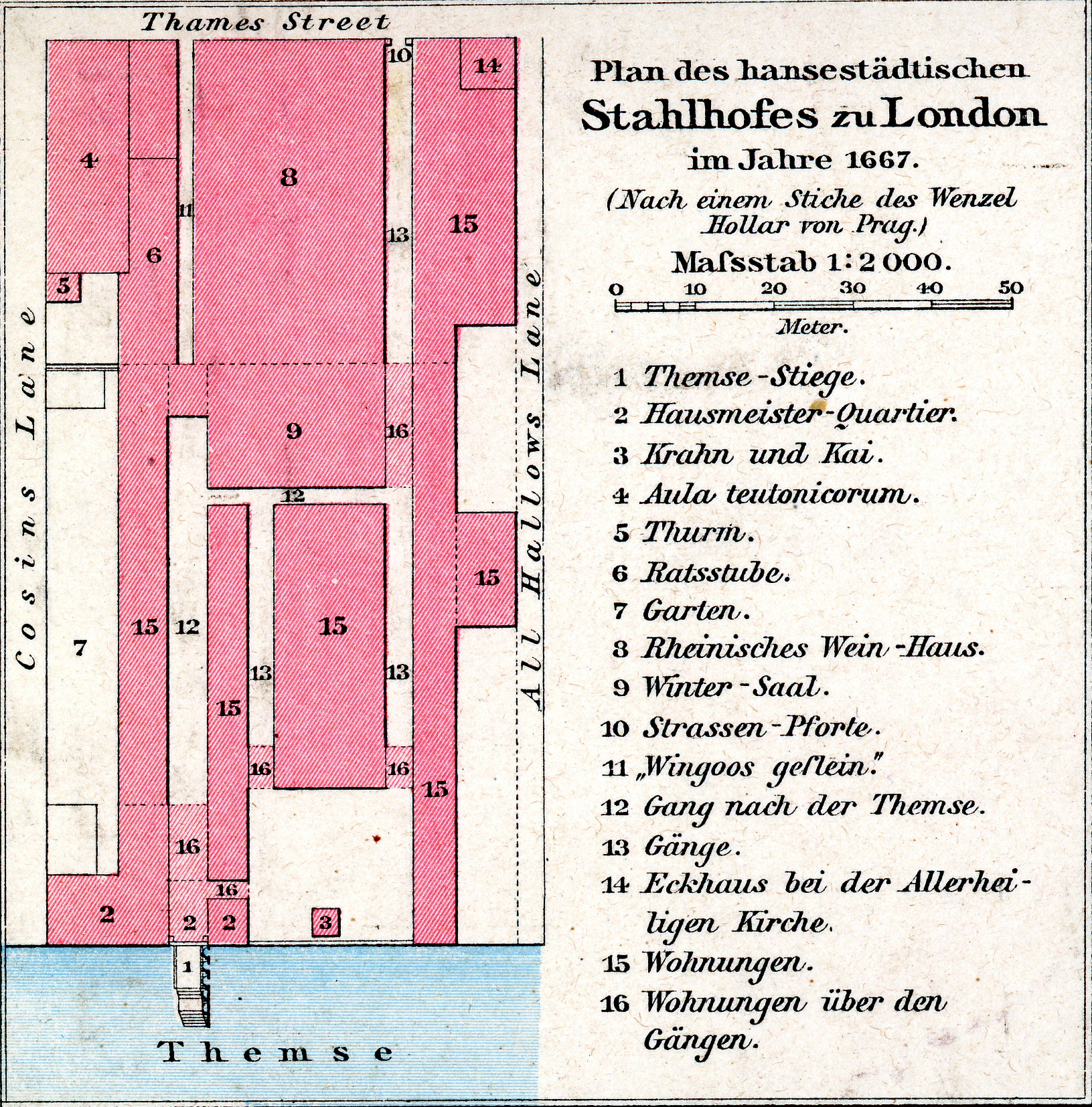

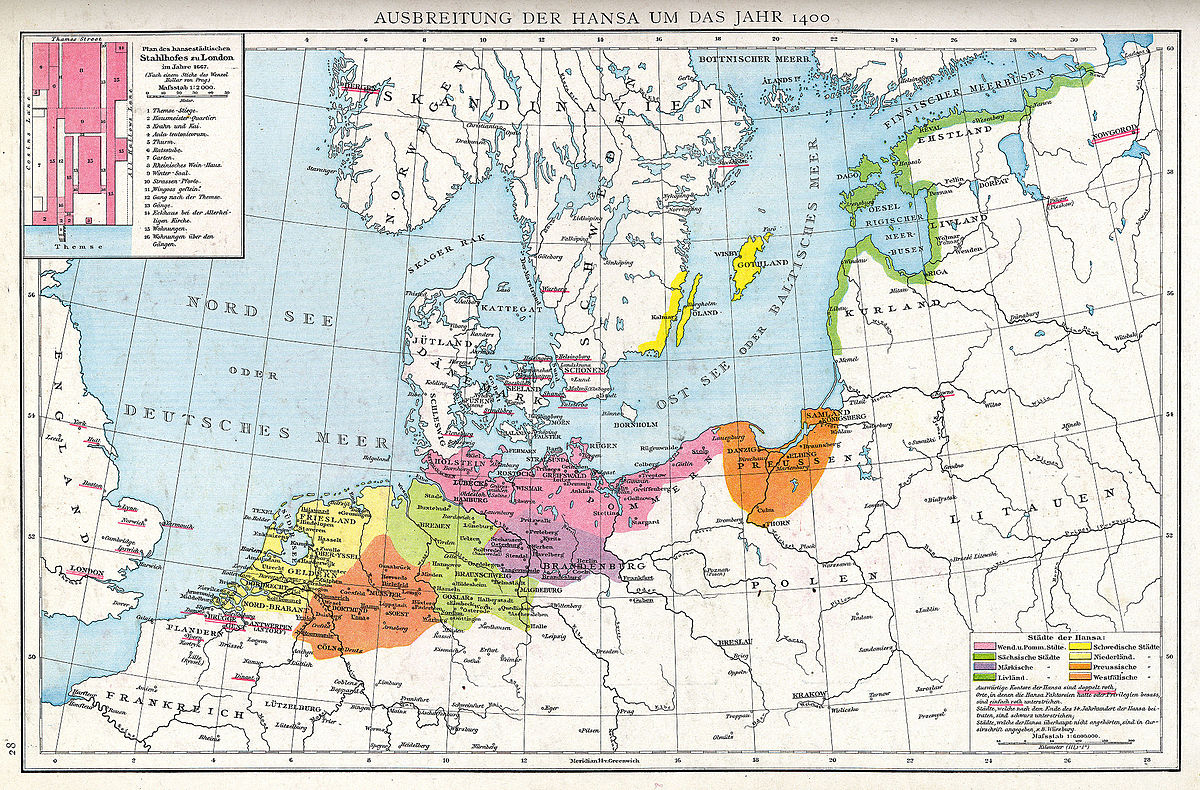

The Steelyard was the chief outpost of the Hanseatic League in the city of London. Located on the north side of the River Thames, slightly west of London Bridge, the Steelyard was home to many wealthy German merchants from the thirteenth century to the end of the sixteenth. It was the central Kontor, or community, of the Hanseatic League in England. The League defined itself as

a firm confederatio of many [German] cities, towns, and communities [designed] for the purpose of ensuring that business enterprises by land and sea should have a desired and favorable outcome and that there should be effective protection against piracies and highwaymen, so that their ambushes should not rob merchants of the goods and valuables(Lloyd 7).

Location

The Steelyard was located on the north bank of the Thames, slightly west of London Bridge and Church Lane, and south of Thames Street. Though nominally in Dowgate Ward, the Steelyard merchants elected their own alderman in their own guildhall (Weinreb and Hibert 824). Of the guildhall itself, Stow notes:

These marchants of Haunce had their Guild hall in Thames street in place aforesaid, by the said Cosin lane. Their hall is large, builded of stone, with three arched gates towards the street, the middlemost whereof is farre bigger then the other, and is seldome opened, the other two be mured up, the same is now called the old hall.

(Stow)

Name and Etymology

The name

Steelyardmay derive from the unit of measure, the stiliard, defined in Salusbury’s 1661 Mathematical Collections and Translations as

a weight sometimes of an hundred pounds(Salusbury). These weights could have been used to measure the weights of imported goods brought to the merchants. However, Weinreb and Hibbert assert that the name derives from

the big scales used in the weighing of imported goods,rather than the weights themselves (Weinreb and Hibbert 824). Alternate spellings and names include

Stele house,

Stele yarde,

Styllyarde,

Steleyarde,

Stiliarde,Stilliard,

Stillyard,

Styleyarde,and the

Guildhall of the Merchants of Cologne.

Significance

The London Steelyard, as well as the Hanseatic League as a whole, was important to English trade until the middle of the sixteenth century. As Stow notes, the principal imports of the Steelyard merchants were

Wheate, Rie, and other grains [...] Cables, Ropes, Mastes, Pitch, Tar, Flax, Hempe, Wainscotes, Wax, Steele, and other profitable marchandires(Stow). Because the Hanseatic League offered a massive boon to trade in their buying and selling of goods, they were offered exemptions from taxes and tariffs (Lloyd 21). These exemptions aggravated anti-alien sentiment throughout England, leading the Merchant Adventurers Company to enter into legal and economic competition with the Hanseatic League from 1407 until the abandonment of the Steelyard in the early seventeenth century (Lloyd 294-295).

The Steelyard was a powerful economic force in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, but by the reign of Elizabeth, piracy and economic sanctions had rendered the once great Steelyard obsolete (Lloyd 344-345). By the early seventeenth century, the Steelyard was usually referred to in popular representations as a place of cheap Rhenish wine

and bumbling Dutchmen. This reputation made it a favorite destination for those looking

for a good time, such as Master Linstock and his ladies in Thomas Dekker and John Webster’s Westward Ho!.

History

While Hanseatic Kontors had been established in England as early as 1157, the exact date of the Steelyard’s creation is uncertain (Lloyd 17). Some historians claim that it was chartered as early as 1237, whilst others claim that its inception can be traced to Henry III’s 1260 proclamation of the Hanse’s right to establish a guildhall in London (Lloyd 19). What is certain is that by 1300 the Steelyard was recognized as

the chief executive authority of the Hanse(Lloyd 37).

Towards the end of the fourteenth century, there were approximately 28 Hanseatic merchants living in the Steelyard (Lloyd 75). The next century brought great difficulties to the Hanseatic League as a whole, as the merchants frequently found themselves embroiled in legal difficulties

with the English government over piracy claims and expiring tax exemptions (Fudge 18-19). As Hanseatic historian T.H. Lloyd notes, the chief grievances of the merchants

were:

(1) The levy and tunnage and poundage; (2) the collection of a poll tax from travellers entering and leaving English territory at Dover and Calais; (3) prolonged delays in obtaining justice; (4) denial of the right to mixed juries, especially in courts of admiralty; (5) denial of immunity from distraint for debts and trespasses of third parties; (6) delay in payment of goods purveyed for the crown; (7) exaction of local tolls at Southampton and Newcastle; (8) denial of the right to sell wine by retail in London.

(Lloyd 143)

Such grievances were favorably addressed in the aftermath of the 1475 Treaty of Utrecht (Lloyd 228-229). In spite of these successes, the English government remained largely unfriendly

to the Steelyard, as well as towards the Hanseatic League as a whole, particularly in the sixteenth century: in 1519 Cardinal Wolsey, under the authority of Henry VIII, accused Steelyard merchants of selling unfinished cloth, compelling the merchants to find sureties

totaling 18,800 pounds (Lloyd 253-254). Wolsey also threatened to levy alien rates of duty and taxation on all Hanseatic merchants,

setting aside the traditional exemptions given to the League (Lloyd 254). Furthermore, the Steelyard was unable to compensate for the adverse balance of trade in provincial Kontors as

it had done in the fifteenth century, leading to massive trade deficits throughout the 1500s (Lloyd 275).

Towards the middle of the century, the political situation in London had become increasingly threatening to the continuation of the Steelyard. In 1554, the Steelyard merchants complained that English traders were given preferential treatment by the

crown, and that the Hanseatic League was in danger of collapsing (Lloyd 297). The situation did not improve once Elizabeth succeeded Mary. By 1598, Elizabeth had formally closed the Steelyard, revoked all the medieval privileges given to the Hanseatic merchants in London, and ordered the remaining merchants in London to leave the country (Beerbühl 29-30). This last demand was later rescinded in favor of allowing the merchants to remain

in London whilst subjecting them to restrictive alien laws that favoured domestic merchants

(Beerbühl 30).

The Hanseatic property in London was seized by the crown, but later returned to the merchants in 1606 by King James. However, after this devastating blow, the merchants of the Steelyard, as well as the Hanseatic league as a whole, would never regain their former glory. Even though Elizabeth rescinded her decision to exile London’s Hanseatic merchants, only eight chose to remain. In 1623 it was reported that only five still occupied the Steelyard (Beerbühl 30-31).

By 1632, the situation was even grimmer—no remaining Hanseatic merchants lived in the Steelyard. In 1666, the vast majority of the medieval buildings in the area were completely destroyed

(Lloyd 345). Despite all of this, the Steelyard properties remained in the hands of the towns of Lubeck, Hamburg, and Bremen until

1853, when they were sold to build the Cannon Street railway station (Lloyd 345, Weinreb and Hibbert 824).

Cultural Activity and References

The Steelyard operated as an all-male, German enclave within London. Women were not allowed within its walls. The merchants and their fellow-countrymen

were forbidden from playing games with Englishmen for fear of quarrels (Weinreb and Hibert 824).

Steelyard merchants patronized German artists in London. Between 1533 and 1536, Hans Holbein the Younger was commissioned to produce eight portraits of prominent Steelyard merchants. These included Georg Gisze, Hans of Antwerp, Hermann Wedigh III, an anonymous member of the Wedigh family, Dirk Tybis, Cyriacus Kale, Derich Born, and Derick Berck (Holman 139). Holbein had also been commissioned in the middle of the sixteenth century to paint two large allegorical pieces for the dining room of the Steelyard guildhall, The Triumph of Riches and The Triumph of Poverty, both of which are now lost (Weinreb and Hibbert 824). Based on Holbein’s extant pen sketches for the paintings, and subsequent work by artists who sought

to replicate the piece (such as Lucas Vosterman the Elder’s own The Triumph of Riches and Triumph of Poverty), art historian Susan Foister suggests that the moral of the allegory of the work

is that

money is the source of sorrow, whether too much or too little(Foister 69).

It is also possible that the Steelyard merchants may have commissioned the famous Copperplate Map of London, because the map-maker has labelled the Hanseatic guildhall in the Steelyard, but none of the other company halls (Ward 1159).

During the reigns of Elizabeth and James, the economic power of the Steelyard was largely in the past. Thus, most references to the area from 1550 onwards tend to be satirical allusions to the League’s former glory, or jokes about the area as a place to get drunk on duty-free Rhenish

wine.

A scene in the first act of Dekker and Webster’s Westward Ho! takes place in a Rhenish wine house in the Steelyard. It features one of the characters, Master Linstock, getting drunk with his ladies and making fun of Hans, their Dutch server.

Thomas Nashe frequently refers to the Steelyard as a place of debauchery. As his narrator notes in Pierce Penniless,

Men[,] when they are idle and know not what to do, saith let us goe to the Stilliard and drinke Rhenish wine(Nashe). Gabriel Harvey later responded to Nashe in a poem titled

The Asses Figgin his work Pierce’s Supererogation:

(Harvey)So long the Rhennish furie of thy braineIncenst with hot fume of a Stilliard climeLowd-lying Nashe, in liquid terms did raineFull of absurdities, and slaundrous ryme

In Isabella Whitney’s

Wyll and Testament,the Steelyard is also referred to as a place of drinking and debauchery. She notes that

(Whitney)At Stiliarde store of wines there beeyour dulled minds to gladAnd handsome men, that must not wedexcept they leave their trade

In Thomas Middleton’s 1627 drama Michaelmas Terme, Short, the crony of a wealthy London cloth merchant, makes a brief joke about the misfortunes of the Steelyard. When asked where to send a worthless cloth, Short remarks that they could send it to

Maister Beggar-land [...] or his Brother Maister Stilliard-downe, there’s little difference(Middleton).

Notes

- See MoEML’s digital edition of

The Wyll and Testament of Isabella Whitney.

(TLG)↑

References

-

Citation

Anonymous.Vanity of vanities or Sir Harry Vane’s picture. To the tune of the Jews corant.

London: n.p., 1660. Rpt. Early English Books Online. Subscription.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Beerbühl, Margrit Schulte. The Forgotten Majority: German Merchants in London, Naturalization, and Global Trade, 1660-1815. Trans. Cynthia Klohr. New York: Berghahn Books.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Dekker, Thomas. Westward Ho. The Dramatic Works of Thomas Dekker. Vol. 2. Ed. Fredson Bowers. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1964.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Foister, Susan. Holbein in England. London: Tate Publishing, 2006.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Fudge, John D. Cargoes, Embargoes, and Emissaries: The Commercial and Political Interaction of England and the German Hanse, 1450-1510. Toronto: U of Toronto, 1995.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Holman, Thomas S.Holbein’s Portraits of the Steelyard Merchants: An Investigation.

Metropolitan Museum Journal 14 (1979): 139-58.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Lloyd, Terrence H. England and the German Hanse: 1157-1611: A Study of Their Trade and Commercial Diplomacy. Cambridge: Cambridge U, 1991.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Middleton, Thomas. Michaelmas Terme. London: Printed by Thomas Purfoot and Edward Allde for A. Johnson and are to be sould at the signe of the White Horse in Paules Churchyard, 1607. Reprint. Internet Archive. Open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Nashe, Thomas. Pierce Penilesse His Supplication to the Divell. London: Printed by Abell Jeffes, for I.B., 1592. Reprint. Early English Books Online. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Salusbury, Thomas. Mathematical Collections and Translations. London: Printed by William Leybourn, 1661. Wing S517. Reprint. Early English Books Online. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Stow, John. A Survey of London. Reprinted from the Text of 1603. Ed. Charles Lethbridge Kingsford. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1908. Reprint. British History Online. Subscription. [Kingsford edition, courtesy of The Centre for Metropolitan History. Articles written 2011 or later cite from this searchable transcription. In the in-text parenthetical reference (Stow; BHO), click on BHO to go directly to the page containing the quotation or source.]This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Ward, Joseph P.Tudor London: A Map and a View.

The Sixteenth Century Journal 33.4 (2002): 1159-1160.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Weinreb, Ben, and Christopher Hibbert, eds. The London Encyclopaedia. New York: St. Martin’s, 1983. [You may also wish to consult the 3rd edition, published in 2008.]This item is cited in the following documents:

Cite this page

MLA citation

The Steelyard.The Map of Early Modern London, edited by , U of Victoria, 20 Jun. 2018, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/STEE2.htm.

Chicago citation

The Steelyard.The Map of Early Modern London. Ed. . Victoria: University of Victoria. Accessed June 20, 2018. http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/STEE2.htm.

APA citation

2018. The Steelyard. In (Ed), The Map of Early Modern London. Victoria: University of Victoria. Retrieved from http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/STEE2.htm.

RIS file (for RefMan, EndNote etc.)

Provider: University of Victoria Database: The Map of Early Modern London Content: text/plain; charset="utf-8" TY - ELEC A1 - Smith, Joul ED - Jenstad, Janelle T1 - The Steelyard T2 - The Map of Early Modern London PY - 2018 DA - 2018/06/20 CY - Victoria PB - University of Victoria LA - English UR - http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/STEE2.htm UR - http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/xml/standalone/STEE2.xml ER -

RefWorks

RT Web Page SR Electronic(1) A1 Smith, Joul A6 Jenstad, Janelle T1 The Steelyard T2 The Map of Early Modern London WP 2018 FD 2018/06/20 RD 2018/06/20 PP Victoria PB University of Victoria LA English OL English LK http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/STEE2.htm

TEI citation

<bibl type="mla"><author><name ref="#SMIT17"><surname>Smith</surname>, <forename>Joul</forename> <forename>L.</forename></name></author> <title level="a">The Steelyard</title>. <title level="m">The Map of Early Modern London</title>, edited by <editor><name ref="#JENS1"><forename>Janelle</forename> <surname>Jenstad</surname></name></editor>, <publisher>U of Victoria</publisher>, <date when="2018-06-20">20 Jun. 2018</date>, <ref target="http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/STEE2.htm">mapoflondon.uvic.ca/STEE2.htm</ref>.</bibl>Personography

-

Janelle Jenstad

JJ

Janelle Jenstad, associate professor in the department of English at the University of Victoria, is the general editor and coordinator of The Map of Early Modern London. She is also the assistant coordinating editor of Internet Shakespeare Editions. She has taught at Queen’s University, the Summer Academy at the Stratford Festival, the University of Windsor, and the University of Victoria. Her articles have appeared in the Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Early Modern Literary Studies, Elizabethan Theatre, Shakespeare Bulletin: A Journal of Performance Criticism, and The Silver Society Journal. Her book chapters have appeared (or will appear) in Performing Maternity in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2007), Approaches to Teaching Othello (Modern Language Association, 2005), Shakespeare, Language and the Stage, The Fifth Wall: Approaches to Shakespeare from Criticism, Performance and Theatre Studies (Arden/Thomson Learning, 2005), Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society (Brill, 2004), New Directions in the Geohumanities: Art, Text, and History at the Edge of Place (Routledge, 2011), and Teaching Early Modern English Literature from the Archives (MLA, forthcoming). She is currently working on an edition of The Merchant of Venice for ISE and Broadview P. She lectures regularly on London studies, digital humanities, and on Shakespeare in performance.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Stub

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

Author of Textual Introduction

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Course Instructor

-

Course Supervisor

-

Course supervisor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Structure and Toponyms)

-

Final Markup Editor

-

GIS Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Modern)

-

Geographical Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Main Transcriber

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Name Encoder

-

Peer Reviewer

-

Primary Author

-

Project Director

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Reviser

-

Second Author

-

Second Encoder

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Janelle Jenstad is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Janelle Jenstad is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Tye Landels-Gruenewald

TLG

Research assistant, 2013-15, and data manager, 2015 to present. Tye completed his undergraduate honours degree in English at the University of Victoria in 2015.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

MoEML Researcher

-

Name Encoder

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

Contributions by this author

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kim McLean-Fiander

KMF

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach, 2015–present; Associate Project Director, 2015–present; Assistant Project Director, 2013-2014; MoEML Research Fellow, 2013. Kim McLean-Fiander comes to The Map of Early Modern London from the Cultures of Knowledge digital humanities project at the University of Oxford, where she was the editor of Early Modern Letters Online, an open-access union catalogue and editorial interface for correspondence from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. She is currently Co-Director of a sister project to EMLO called Women’s Early Modern Letters Online (WEMLO). In the past, she held an internship with the curator of manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library, completed a doctorate at Oxford on paratext and early modern women writers, and worked a number of years for the Bodleian Libraries and as a freelance editor. She has a passion for rare books and manuscripts as social and material artifacts, and is interested in the development of digital resources that will improve access to these materials while ensuring their ongoing preservation and conservation. An avid traveler, Kim has always loved both London and maps, and so is particularly delighted to be able to bring her early modern scholarly expertise to bear on the MoEML project.Roles played in the project

-

Associate Project Director

-

Author

-

Author of MoEML Introduction

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Contributor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Contributor

-

Data Manager

-

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (People)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Managing Editor

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Research Fellow

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Second Author

-

Secondary Author

-

Secondary Editor

-

Toponymist

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Kim McLean-Fiander is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Kim McLean-Fiander is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Joey Takeda

JT

Programmer, 2018-present; Junior Programmer, 2015 to 2017; Research Assistant, 2014 to 2017. Joey Takeda is an MA student at the University of British Columbia in the Department of English (Science and Technology research stream). He completed his BA honours in English (with a minor in Women’s Studies) at the University of Victoria in 2016. His primary research interests include diasporic and indigenous Canadian and American literature, critical theory, cultural studies, and the digital humanities.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Stub

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Date Encoder

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Bibliography)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Agas)

-

Junior Programmer

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Encoder

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Second Author

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Editor

Contributions by this author

Joey Takeda is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Joey Takeda is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Martin D. Holmes

MDH

Programmer at the University of Victoria Humanities Computing and Media Centre (HCMC). Martin ported the MOL project from its original PHP incarnation to a pure eXist database implementation in the fall of 2011. Since then, he has been lead programmer on the project and has also been responsible for maintaining the project schemas. He was a co-applicant on MoEML’s 2012 SSHRC Insight Grant.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of abstract

-

Conceptor

-

Encoder

-

Name Encoder

-

Post-conversion and Markup Editor

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

Contributions by this author

Martin D. Holmes is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Martin D. Holmes is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Amy Tigner

Amy Tigner is a MoEML Pedagogical Partner. She is Associate Professor of English at the University of Texas, Arlington, and the Editor-in-Chief of Early Modern Studies Journal. She is the author of Literature and the Renaissance Garden from Elizabeth I to Charles II: England’s Paradise (Ashgate, 2012) and has published in ELR, Modern Drama, Milton Quarterly, Drama Criticism, Gastronomica and Early Theatre. Currently, she is working on two book projects: co-editing, with David Goldstein, Culinary Shakespeare, and co-authoring, with Allison Carruth, Literature and Food Studies.Roles played in the project

-

Guest Editor

Amy Tigner is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Joul L. Smith

JLS

Student contributor enrolled in English 5308: Shakespeare and Early Modern Urban/Rural Nature at the University of Texas, Arlington in the Fall 2014 session, working under the guest editorship of Amy Tigner.Roles played in the project

-

Author

Contributions by this author

Joul L. Smith is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Joul L. Smith is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Thomas Dekker is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth Tudor I Queen of England and Ireland

(b. 7 September 1533, d. 24 March 1603)Queen of England and Ireland.Elizabeth I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Henry VIII is mentioned in the following documents:

-

James VI and I

King James Stuart VI and I

(b. 1566, d. 1625)King of Scotland, England, and Ireland.James VI and I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Mary I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thomas Middleton is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thomas Nashe is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Stow is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Webster is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Isabella Whitney is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thomas Wolsey is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Master Linstock is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Hans Holbein the Younger is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Lucas Vorsterman is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Georg Gisze

(b. 2 April 1497, d. 3 February 1562)Prominent Hanseatic merchant who resided in the Steelyard. Painted by Hans Holbein the Younger.Georg Gisze is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Hans of Antwerp

Prominent Hanseatic merchant who resided in the Steelyard. Painted by Hans Holbein the Younger.Hans of Antwerp is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Hermann von Wedigh III

(d. 1560)Prominent Hanseatic merchant who resided in the Steelyard. Painted by Hans Holbein the Younger.Hermann von Wedigh III is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Dirk Tybis

Prominent Hanseatic merchant who resided in the Steelyard. Painted by Hans Holbein the Younger.Dirk Tybis is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Cyriacus Kale

Prominent Hanseatic merchant who resided in the Steelyard. Painted by Hans Holbein the Younger.Cyriacus Kale is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Derich Born

(b. 1510, d. 1549)Prominent Hanseatic merchant who resided in the Steelyard. Painted by Hans Holbein the Younger.Derich Born is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Derick Berck

Prominent Hanseatic merchant who resided in the Steelyard. Painted by Hans Holbein the Younger.Derick Berck is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Mr. Wedigh

Member of the Wedigh family and a prominent Hanseatic merchant who resided in the Steelyard. Painted by Hans Holbein the Younger.Mr. Wedigh is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Hans is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Gabriel Harvey is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Short

Character in Thomas Middleton’s Michaelmas Terme.Short is mentioned in the following documents:

Locations

-

The Thames is mentioned in the following documents:

-

London Bridge

From the time the first wooden bridge in London was built by the Romans in 52 CE until 1729 when Putney Bridge opened, London Bridge was the only bridge across the Thames in London. During this time, several structures were built upon the bridge, though many were either dismantled or fell apart. John Stow’s 1598 A Survey of London claims that the contemporary version of the bridge was already outdated by 994, likely due to the bridge’s wooden construction (Stow 1:21).London Bridge is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Guildhall of the Hanseatic League is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Church Lane (All Hallows) is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thames Street

Thames Street was the longest street in early modern London, running east-west from the ditch around the Tower of London in the east to St. Andrew’s Hill and Puddle Wharf in the west, almost the complete span of the city within the walls.Thames Street is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Dowgate Ward

MoEML is aware that the ward boundaries are inaccurate for a number of wards. We are working on redrawing the boundaries. This page offers a diplomatic transcription of the opening section of John Stow’s description of this ward from his Survey of London.Dowgate Ward is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Cousin Lane is mentioned in the following documents:

Organizations

-

The Merchant Venturers’ Company of London

The Worshipful Company of Merchant Venturers of London

The Merchant Venturers’ Company of London was one of the lesser livery companies of London.This organization is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Hanseatic League

Confederation of German merchant guilds and market towns with outposts throughout Northern Europe, including England.This organization is mentioned in the following documents:

Variant spellings

-

Documents using the spelling

gate of Guild Hall of the Merchants of Colleyne

-

Documents using the spelling

Guildhall of the Merchants of Cologne

-

Documents using the spelling

London Steelyard

-

Documents using the spelling

Steelyard

-

Documents using the spelling

Stele house

-

Documents using the spelling

stele house

-

Documents using the spelling

Stele house

-

Documents using the spelling

Stele yarde

-

Documents using the spelling

Steleyarde

-

Documents using the spelling

Stiliard

-

Documents using the spelling

Stiliarde

-

Documents using the spelling

Stilliard

-

Documents using the spelling

Stillyard

-

Documents using the spelling

Stilyard

-

Documents using the spelling

stilyarde

-

Documents using the spelling

Styleyarde

-

Documents using the spelling

Styllyarde

-

Documents using the spelling

The Steelyard