Bear Garden

Introduction

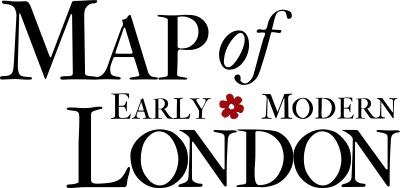

On the Agas map, the Bear Garden is a circular arena with an open roof and a clear label—

The Bearebayting—located in the Liberty of the Clink, Southwark. The Bear Garden was never a garden, but rather a polygonal bearbaiting arena whose exact locations across time are not known (Mackinder and Blatherwick 18). To complicate matters of historical accuracy, by 1620,

bear gardenwas the generic name given to a set of permanent structures—wooden arenas, dog kennels, bear pens—dedicated to bearbaiting, and rebuilt on various occasions during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (Mackinder and Blatherwick 19). Prior to the mid-sixteenth century, animal baiting occurred in an open field, so it was significant that the Elizabethans established permanent buildings for the practice, which typically occurred two days a week (including Sundays).

Location on Early Maps

Locating the first permanent structure is difficult. Henry Polsted is thought to be the first recorded owner of the property where one of the Bear Gardens would eventually be built. In 1538/9, Polsted bought property from Ralph Sadler, who received the Prioress of Stratford’s land at the Dissolution (Mackinder and Blatherwick 9). The first recorded use of Polsted’s land for bearbaiting occurs in a lease of 1552, which includes

a capital curtilage called le Beara yarde with le Berehouse and a garden(Roberts and Godfrey). Mackinder and Blatherwick believe that there was a second bear garden operated by William Payne and built on part of the Bishop of Winchester’s land.

Immediately west of the Bear Garden on the Agas map is a second, similar edifice labeled The

Bolle baiting.Some historians doubt that a separate, freestanding arena devoted to bullbaiting existed beyond the early sixteenth century, despite the evidence of the Agas Map. As W.W. Braines observes,

there is no record of a place on the Bankside reserved specially for the baiting of bulls, but there is plenty of evidence that bulls (and other animals) were baited at the bear-rings(Braines 48). Giles E. Dawson makes a similar argument based on an eyewitness account by a Venetian, Alessandro Magno, who wrote in 1562 that bull and bearbaiting occurred in the same arena. Dawson argues that, if there were two distinct arenas for each sport so proximate, Magno (and others) would have mentioned this fact. Braines speculates that Agas’s bullbaiting arena may have been the newer Bear Garden, while the eastern ring was an older version. Mackinder and Blatherwick, however, believe that the

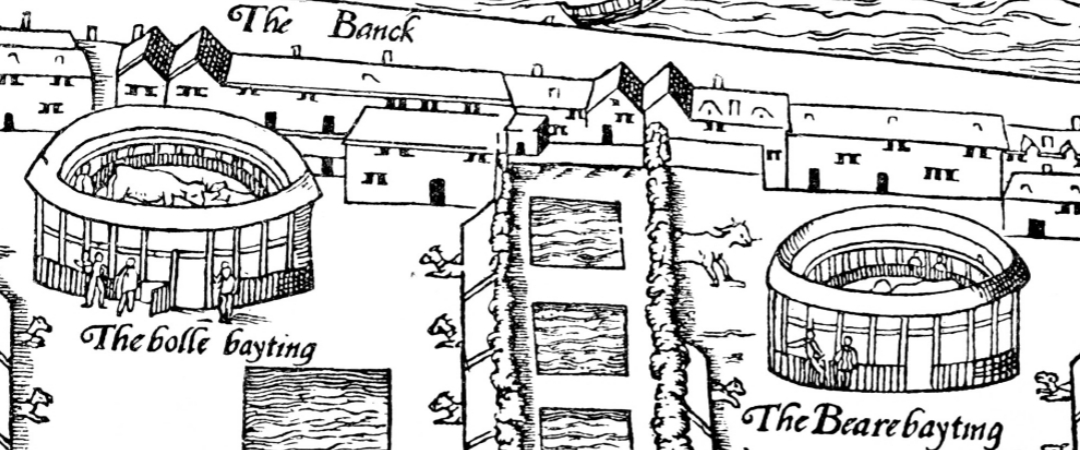

earliest documentary evidencefor animal baiting is a bullring on an unpublished manuscript map of Southwark dated 1542, which seems to be corroborated by Wyngaerde’s panorama of 1543 (Mackinder and Blatherwick 18). John Stow’s Survey of London supports the existence of two arenas, but states that both were bear gardens. On Claes van Visscher’s 1616 map of London, the two identical arenas appear again, but their names change. The eastern ring, Agas’s Bear Garden, becomes the Globe theatre and Agas’s bullbaiting arena to the west becomes the Bear Garden. For Braines, whose real concern is the site of the Globe, Visscher reproduces the Agas map’s inaccuracies; visually, Visscher’s map suggests that the Globe is built on top of an animal baiting arena. It is not until Wenceslas Hollar’s 1647

long viewof London that these two buildings are drawn and positioned accurately—but their names, as Braines argues, are again incorrect. Hollar’s

The Globe,a smaller arena near the Thames, is really the Bear Garden, while Hollar’s

Beere bayting h(which has a tiring house) is the real Globe.

long viewmap of 1647. Image courtesy of the Folger Digital Image Collection.

History

Bear Garden shared its Bankside home with both theatres and brothels. Martha Carlin characterizes Southwark as

a haven of criminals and forbidden practices within sight of the royal court and law courts at Westminster(Carlin xix). Early references to Bear Garden—including Stow’s Survey of London and John Leland’s Antiquities—often precede or follow a discussion of Southwark’s brothels. In the 1603 Survey, Stow writes,

Now to returne to the Weſt banke, there be two Beare gardens, the olde and the new places, wherein be kept Beares, Buls and other beaſtes to be bayted. As also Maſtiues in ſeuerall kenels, nouriſhed to baite them. These Beares and other Beaſts are there bayted in plottes of ground, ſcaffolded about for the Beholders to stand ſafe(Stow sig. 2D4r). He then shifts to a brief legal history of the

Bordello or ſtewesand their privileges, which date to the reign of Edward III. John Bagford’s

A Letter to the Publisher,part of the prefatory material in John Leland’s Antiquities, suggests that the stews existed long before baiting arenas:

As to the Brothel-Houſes formerly in Southwark, we find a Statute as old as the Reign of Edw. III. for their Toleration [...] ’tis probable that they were firſt eſtabliſhed by the Romans, (for the Bull and Bear Garden in that Place is but of late Settlement,) who had alſo a Play-Houſe on that ſide, and had their Abode very much in Southwark, which was then a Place of Fortification(Bagford sig. K2r). An ordinance dated April 1546 from the reign of Henry VIII abolishes both stews and bearbaiting (Roberts and Godfrey). However, a few months later in September 1546, the crown granted a license to Thomas Fluddie, yeoman of His Majesty’s bears, to

make pastimewith the king’s bears at the stews (Roberts and Godfrey).

Bearbaiting is more clearly documented in the seventeenth century. In 1594 Edward Alleyn began to buy shares of interest in the Bear Garden on Polsted’s property (now granted by the Queen to Robert Liveseye and Gerrard Gore). Alleyn continued to be involved in its operation until his death in 1626 (Höfele 7, Mackinder and Blatherwick 20). On 24 November 1604, Henslowe and Alleyn were granted a royal patent for

Mastership of the Game of Bears, Bulls and Mastiff Dogs(Greg 101). The document gives Henslowe, Alleyn, and their deputies authority to

bayete or cause to be baytedthe crown’s bears (Greg 101). Henslowe and Alleyn jointly held this office until 1616.

During the Commonwealth period, bearbaiting continued despite Puritan opposition.

Briefly closed in November 1643, the Garden must have been open again by July 1645, when it appears in a

royalist newsbookthat

accuses the Parliament of even stooping to lure young men to the Bear Garden under the guise of showing a new kind of bear-baiting, and then impressing them into the Army(Hotson 278). The Bear Garden continued to operate until 9 February 1655, when the Hope Theatre (alias Bear Garden) was pulled down, the mastiffs were sent to Jamaica, and all of the bears (except a single white bear cub) were shot and killed by musketeers under the order of Colonel Thomas Pride, sheriff of Surrey (Ravelhofer 292). The Hope was converted to tenements a month later. Bearbaiting returned after the Restoration, however, with Charles II opening a new arena south of Henslowe’s in 1662 (Hotson 288). The last recorded reference to the Bear Garden is an advertisement published in 1682 (Roberts and Godfrey).

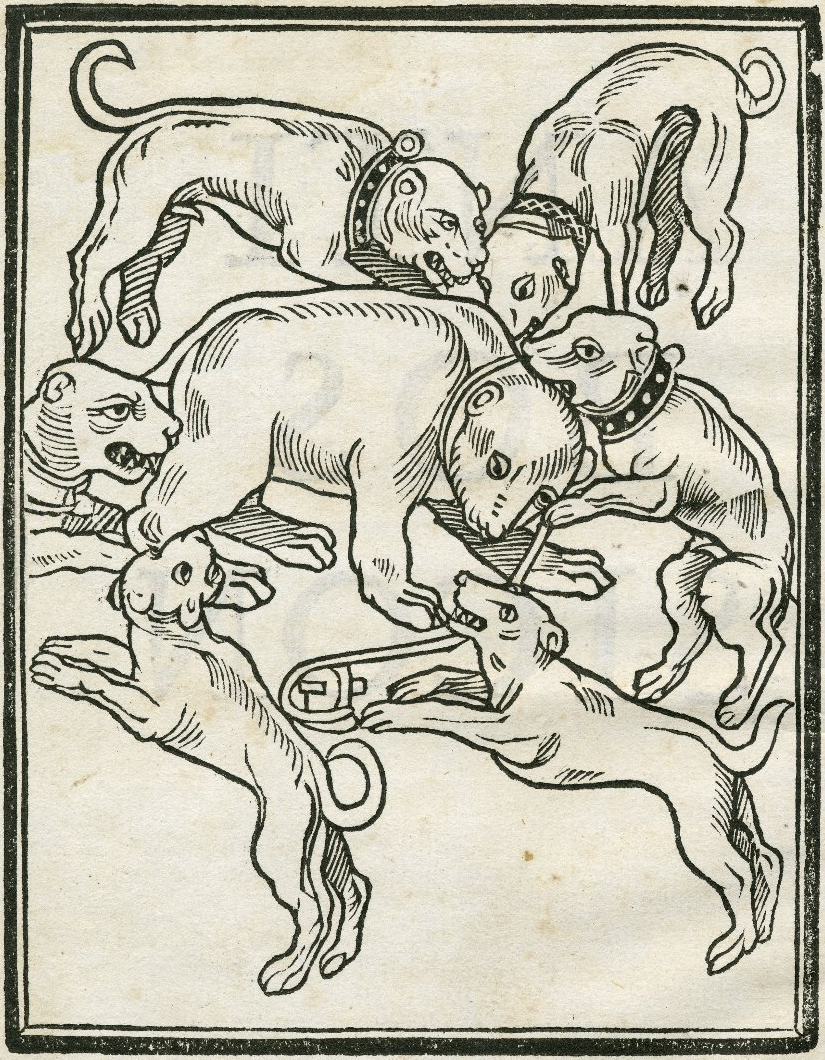

Bears and English Mastiffs

Bears were trained by their bearwards, almost like Roman gladiators, to defend themselves

in carefully timed and choreographed matches against English mastiffs, a particular

breed of dog known for its courage (Ravelhofer 288). When the bears were old and blinded by wounds from dogs, they were simply staked

to the ground and whipped until blood poured down their backs (Ravelhofer 288). As Ravelhofer argues, when bears were not beaten, but rather trained to dance or

tumble,the bearward’s methods were equally horrific. Even so, there were many vocal supporters of bearbaiting, including watermen, whose livelihoods depended on ferrying passengers to and from Southwark. John Taylor, known as the

water poet,promoted animal baiting through his published pamphlet, Bull, Beare, and Horse, Cut, Curtaile, and Longtaile (1638), and even concludes with a list of each bear’s name:

(Taylor sig. D9r-D9v)

Taylor appears to list these bears by name for a specific reason. Nick de Somogyi argues

that, since

the anonymous dogs [...] were expendable,while the bears—especially George Stone, Harry Hunks, and Sackerson—attained celebrity status, such specificity suggests a broad cultural acceptance and awareness of the bears’ significance (de Somogyi 102). For example, Master Slender boasts that he has seen

Sackerſon looſe, twenty times, and haue taken him by the Chainein The Merry Wives of Windsor (The Merry Wives of Windsor [F1] D3r). Oscar Brownstein, on the other hand, argues that, although the bears were given human names,

the spectator’s interest was in the dogs, their willingness, pursuit, attack, and tenacity:

it was the dogs which won the prizes which were offered and it was the dog’s owners, primarily, who made the wagers(Brownstein 243-244). Regardless which creature was the object of immediate attention at the baiting event, the specific naming and cultural celebrity status of the bears is sufficient to suggest public awareness of them as individual combatants.

Bearbating and the Renaissance Stage

Studies of bearbaiting by literary critics and cultural historians often consider

the mindset whereby early modern Londoners could consider bearbaiting as a form of

entertainment. Such questioning might appear significant for those Shakespeareans

who recognize that bearbaiting arenas and playhouses practically overlapped in popular

appeal, while, in the case of the Hope Theatre, the two activities actually did overlap. Ravelhofer proposes that, on at least two

occasions, the bears were perhaps called upon to perform in plays: (1) King James’s two white polar bears (also named in Taylor’s list) might have drawn Prince Henry’s chariot in Ben Jonson’s court masque, Oberon (1611), and (2) one of the bears might have appeared in Mucedorus (1610 or 1611) and The Winter’s Tale (1611, 1613) (Ravelhofer 297-298). Ravelhofer’s conjecture is counter to the traditionally held belief that these

instances refer to actors in bear costumes. Because of the physical proximity between

blood sports arenas and the Bankside theatres, and what Andreas Höfele refers to as the

typological kinship of the buildings,it seems reasonable to suggest that there are crucial parallels between these worlds, one of which (bearbaiting) has ceased to exist (Höfele 6). We tend to identify the Elizabethan and Jacobean stage as a site of philosophical inquiry, artistic creation, and humanist thought, while we criminalize dogfighting, cockfighting, and animal baiting. How could the same crowd attend both events without experiencing cognitive dissonance?

For Jacqueline Vanhoutte, the Bear Garden appealed to early modern spectators since, when a strong, powerful beast was tied

to the stake and rendered weak, if not impotent, this enforced bondage mirrored the

affairs of men who likewise suffer impotency when confronted with the vagaries of

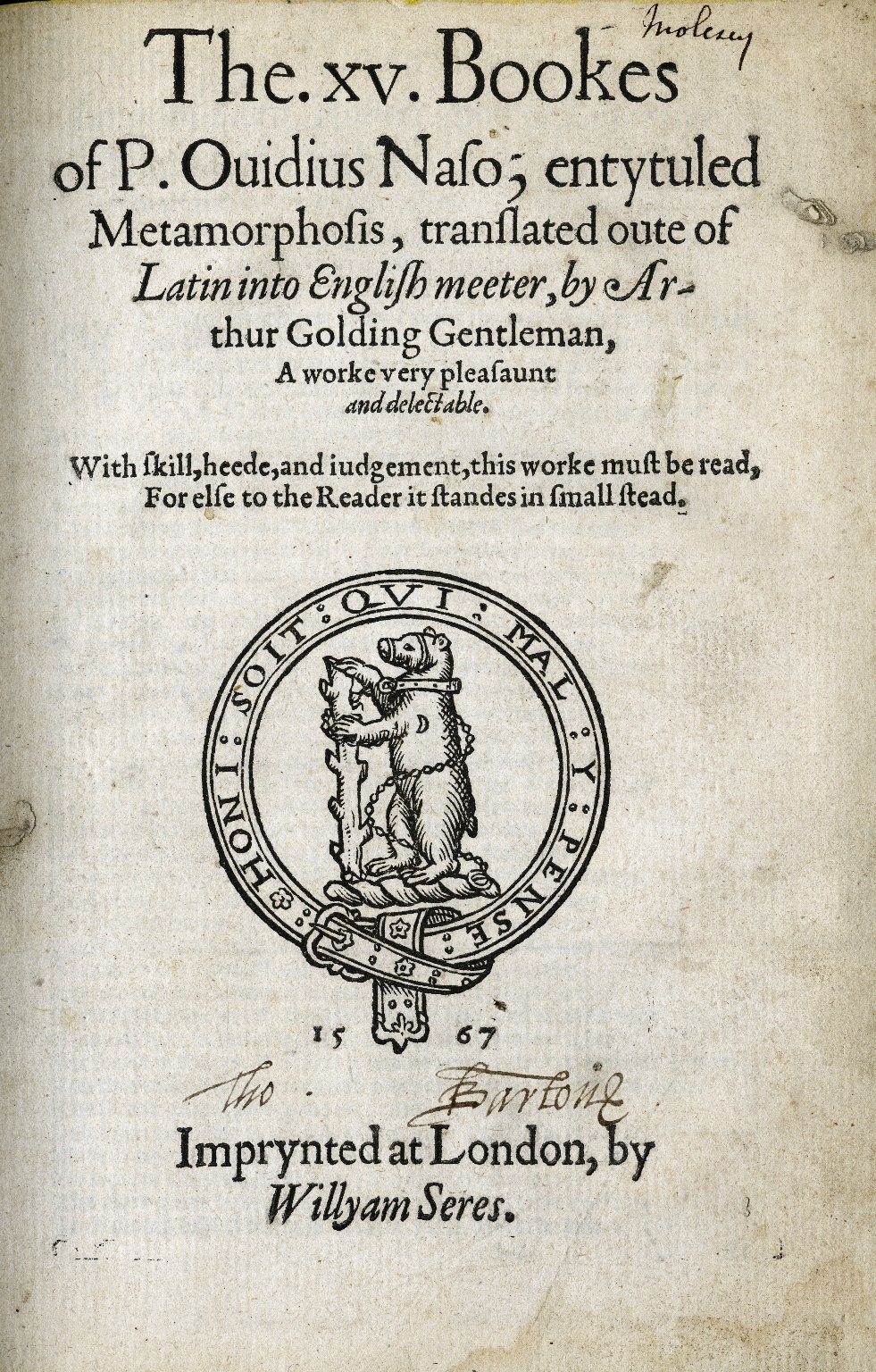

life. Vanhoutte illustrates this by focusing on Robert Dudley, the Earl of Leicester, who displayed his family’s crest—a bear tied to the stake—on

so many print publications that the symbol was eventually considered illustrative

of his own plight. For example, see the title-page to a selection from Arthur Golding’s translation of Ovid, The xv. Bookes of P. Ouidius Naso, entytuled Metamorphosis (1567). Dudley’s critics claimed that the earl’s relationship to Elizabeth I was that of a staked bear to its currish tormenters: with dog-like tenacity, Elizabeth supposedly overpowered, emasculated, and silenced him. Vanhoutte also argues that crowds identified with the baited bear, on whom they projected their

own struggle in unfair fights with authority or in the ongoing battles of daily life.

This use of bearbaiting language as a resigned acceptance of a character’s fate can

be found in Shakespeare, especially with Gloucester’s prescient sense of imminent danger in King Lear, and Macbeth’s defiant rage against his enemies. As Macbeth says in 5.7,

They haue tied me to a ſtake, I cannot flye, [b]ut Beare-like I muſt fight the courſe. What’s he [t]hat was not borne of Woman? Such a one [a]m I to feare, or none(Macbeth [F1] sig. 2N3v). And as Gloucester laments in 3.7 of King Lear, he says

I am tyed to’th’Stake, / And I must ſtand the Courſe(King Lear [F1] sig. 2R4v).

Cultural critics also note that bearbaiting, while obviously relying on blood sport,

spectacle, and violence, was nevertheless often advertised as festive and comical.

In addition, as Stephen Dickey notes when considering the undeniable

violence of bearbaiting,records exist of animals refusing to fight or of stalemate baiting endings, which appear to confirm how

inconclusivesuch violence might appear in a

typical bearbaiting match(Dickey 260). Ravelhofer likewise acknowledges that baiting was

a showpiece of controlled violence under the auspices of a master-producerwhere

opponents could be separated before serious harm ensued(Ravelhofer 288). Whatever our modern predisposition and opposition to blood sport activities, it is important to recognize the sites of baitings, such as those held at Bear Garden, as culturally significant in an early modern historical context and no more or less likely to be condemned than their near neighbors, London’s playhouses.

Additional Resources

MoEML recommends that teachers and students look at the

How to Track a Bear in Southwarklearning module created by MoEML advisory board member Sally-Beth MacLean and her colleagues at the University of Toronto.

References

-

Citation

Bagford, John.A Letter to the Publisher.

Antiquarii de Rebus Britanniccis Collectanea. By John Leland. Ed. Thomas Hearne. London: Impensis Gul. and Jo. Richardson, 1770. Rpt. Eighteenth Century Collections Online. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Bird, James, ed. Shoreditch. Survey of London. Vol. 8. London: London County Council, 1922. Reprint. British History Online. Open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Braines, W.W. The Site of the Globe Playhouse, Southwark. London: Hodder and Stoughton Ltd., 1924.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Brownstein, Oscar..The Popularity of Baiting in England Before 1600: A Study in Social and Theatrical History.

Educational Theatre Journal 21.3 (1969): 237-250.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Carlin, Martha. Medieval Southwark. London: Hambledon P, 1996.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Dawson, Giles E.London’s Bull-Baiting and Bear-Baiting Arena in 1562.

Shakespeare Quarterly 15.1 (1964): 97-101.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Dickey, Stephen.Shakespeare’s Mastiff Comedy.

Shakespeare Quarterly 42 (1991): 255-275.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Greg, Walter W., ed. Henslowe Papers: Being Documents Supplementary to Henslowe’s Diary. London: A.H. Bullen, 1907.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Hagen, Tanya, Sally-Beth MacLean, Alexandra Bolintineanu, and John Estabillo, devs. How to Track a Bear in Southwark. U of Toronto. Open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Hotson, J. Leslie.Bear Gardens and Bear-Baiting During the Commonwealth.

PMLA 40.2 (1925): 276-288.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Höfele, Andreas. Stage, Stake, and Scaffold: Humans and Animals in Shakespeare’s Theatre. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2011.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Jonson, Ben. Oberon, The Faery Prince. The Workes of Benjamin Jonson. Vol. 1. London: Will Stansby, 1616. Sig. 4N2r-2N6r. Reprint. Early English Books Online. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Lily, William. Antibossicon. London: In Aedibus Pynsonianis, 1521. Reprint. Early English Books Online. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Mackinder, Anthony and Simon Blatherwick. Bankside Excavations at Benbow House Southwark London SE1. London: Museum of London Archaeology Service, 2000.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Mucedorus. Rev. ed. London: Imprinted by William Jones, dwelling neare Holborne Conduit at the Signe of the Gunne. 1610. STC 18232. Reprint. Early English Books Online. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Ovid. The xv. Bookes of P. Ouidius Naso, entytuled Metamorphosis. Trans. Arthur Golding. London: Willyam Seres, 1567. Reprint. Folger Digital Image Collection. Open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Ravelhofer, Barbara.Beasts of Recreacion

: Henslowe’s White Bears.English Literary Renaissance

32 (2002): 287-323.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Roberts, Howard and Walter H. Godfrey, eds. Bankside (The Parishes of St. Saviour and Christchurch Southwark). Survey of London. Vol. 22. London: London County Council, 1950. Reprint. British History Online. Open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Shakespeare, William. The Merry Wives of Windsor. Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies [TheFirst Folio

]. London: Printed by Isasac Jaggard and Edward Blount, 1623. Sig. D2r-E6v. Rpt. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Shakespeare, William. The Tragedie of Macbeth. Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies [TheFirst Folio

]. London: Printed by Isasac Jaggard and Edward Blount, 1623. Sig. 2L6r-2N4r. Rpt. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Shakespeare, William. The Tragedie of King Lear. Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies [TheFirst Folio

]. London: Printed by Isasac Jaggard and Edward Blount, 1623. Sig. 2Q2r-2S3r. Rpt. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Somogyi, Nick de.Shakespeare and the Three Bears.

New Theature Quarterly 27.2 (2011): 99-113.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Stow, John. A suruay of London· Conteyning the originall, antiquity, increase, moderne estate, and description of that city, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow citizen of London. Since by the same author increased, with diuers rare notes of antiquity, and published in the yeare, 1603. Also an apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that citie, the greatnesse thereof. VVith an appendix, contayning in Latine Libellum de situ & nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. London: John Windet, 1603. STC 23343. University of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign Campus) copy Reprint. Early English Books Online. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Taylor, John. Bull, Beare, and Horse, Cut, Curtaile, and Longtaile. London: M. Parsons, 1638. STC 23739. Reprint. Early English Books Online. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Vanhoutte, Jacqueline.Age in Love: Falstaff Among the Minions of the Moon.

English Literary Renaissance 43 (2013): 86-127.This item is cited in the following documents:

Cite this page

MLA citation

, and .

Bear Garden.The Map of Early Modern London, edited by , U of Victoria, 20 Jun. 2018, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/BEAR1.htm.

Chicago citation

, and .

Bear Garden.The Map of Early Modern London. Ed. . Victoria: University of Victoria. Accessed June 20, 2018. http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/BEAR1.htm.

APA citation

, & . 2018. Bear Garden. In (Ed), The Map of Early Modern London. Victoria: University of Victoria. Retrieved from http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/BEAR1.htm.

RIS file (for RefMan, EndNote etc.)

Provider: University of Victoria Database: The Map of Early Modern London Content: text/plain; charset="utf-8" TY - ELEC A1 - Kelley, Shannon A1 - Fairfield University English 213 Fall 2014 Student Group 3 ED - Jenstad, Janelle T1 - Bear Garden T2 - The Map of Early Modern London PY - 2018 DA - 2018/06/20 CY - Victoria PB - University of Victoria LA - English UR - http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/BEAR1.htm UR - http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/xml/standalone/BEAR1.xml ER -

RefWorks

RT Web Page SR Electronic(1) A1 Kelley, Shannon A1 Fairfield University English 213 Fall 2014 Student Group 3 A6 Jenstad, Janelle T1 Bear Garden T2 The Map of Early Modern London WP 2018 FD 2018/06/20 RD 2018/06/20 PP Victoria PB University of Victoria LA English OL English LK http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/BEAR1.htm

TEI citation

<bibl type="mla"><author><name ref="#KELL1"><surname>Kelley</surname>, <forename>Shannon</forename></name></author>, and <author><name ref="#FAIR2_3" type="org">Fairfield University English 213 Fall 2014 Student Group 3</name></author>. <title level="a">Bear Garden</title>. <title level="m">The Map of Early Modern London</title>, edited by <editor><name ref="#JENS1"><forename>Janelle</forename> <surname>Jenstad</surname></name></editor>, <publisher>U of Victoria</publisher>, <date when="2018-06-20">20 Jun. 2018</date>, <ref target="http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/BEAR1.htm">mapoflondon.uvic.ca/BEAR1.htm</ref>.</bibl>Personography

-

Janelle Jenstad

JJ

Janelle Jenstad, associate professor in the department of English at the University of Victoria, is the general editor and coordinator of The Map of Early Modern London. She is also the assistant coordinating editor of Internet Shakespeare Editions. She has taught at Queen’s University, the Summer Academy at the Stratford Festival, the University of Windsor, and the University of Victoria. Her articles have appeared in the Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Early Modern Literary Studies, Elizabethan Theatre, Shakespeare Bulletin: A Journal of Performance Criticism, and The Silver Society Journal. Her book chapters have appeared (or will appear) in Performing Maternity in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2007), Approaches to Teaching Othello (Modern Language Association, 2005), Shakespeare, Language and the Stage, The Fifth Wall: Approaches to Shakespeare from Criticism, Performance and Theatre Studies (Arden/Thomson Learning, 2005), Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society (Brill, 2004), New Directions in the Geohumanities: Art, Text, and History at the Edge of Place (Routledge, 2011), and Teaching Early Modern English Literature from the Archives (MLA, forthcoming). She is currently working on an edition of The Merchant of Venice for ISE and Broadview P. She lectures regularly on London studies, digital humanities, and on Shakespeare in performance.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Stub

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

Author of Textual Introduction

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Course Instructor

-

Course Supervisor

-

Course supervisor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Structure and Toponyms)

-

Final Markup Editor

-

GIS Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Modern)

-

Geographical Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Main Transcriber

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Name Encoder

-

Peer Reviewer

-

Primary Author

-

Project Director

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Reviser

-

Second Author

-

Second Encoder

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Janelle Jenstad is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Janelle Jenstad is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Tye Landels-Gruenewald

TLG

Research assistant, 2013-15, and data manager, 2015 to present. Tye completed his undergraduate honours degree in English at the University of Victoria in 2015.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

MoEML Researcher

-

Name Encoder

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

Contributions by this author

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kim McLean-Fiander

KMF

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach, 2015–present; Associate Project Director, 2015–present; Assistant Project Director, 2013-2014; MoEML Research Fellow, 2013. Kim McLean-Fiander comes to The Map of Early Modern London from the Cultures of Knowledge digital humanities project at the University of Oxford, where she was the editor of Early Modern Letters Online, an open-access union catalogue and editorial interface for correspondence from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. She is currently Co-Director of a sister project to EMLO called Women’s Early Modern Letters Online (WEMLO). In the past, she held an internship with the curator of manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library, completed a doctorate at Oxford on paratext and early modern women writers, and worked a number of years for the Bodleian Libraries and as a freelance editor. She has a passion for rare books and manuscripts as social and material artifacts, and is interested in the development of digital resources that will improve access to these materials while ensuring their ongoing preservation and conservation. An avid traveler, Kim has always loved both London and maps, and so is particularly delighted to be able to bring her early modern scholarly expertise to bear on the MoEML project.Roles played in the project

-

Associate Project Director

-

Author

-

Author of MoEML Introduction

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Contributor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Contributor

-

Data Manager

-

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (People)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Managing Editor

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Research Fellow

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Second Author

-

Secondary Author

-

Secondary Editor

-

Toponymist

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Kim McLean-Fiander is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Kim McLean-Fiander is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Joey Takeda

JT

Programmer, 2018-present; Junior Programmer, 2015 to 2017; Research Assistant, 2014 to 2017. Joey Takeda is an MA student at the University of British Columbia in the Department of English (Science and Technology research stream). He completed his BA honours in English (with a minor in Women’s Studies) at the University of Victoria in 2016. His primary research interests include diasporic and indigenous Canadian and American literature, critical theory, cultural studies, and the digital humanities.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Stub

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Date Encoder

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Bibliography)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Agas)

-

Junior Programmer

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Encoder

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Second Author

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Editor

Contributions by this author

Joey Takeda is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Joey Takeda is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Sally-Beth MacLean is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Sally-Beth MacLean is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Martin D. Holmes

MDH

Programmer at the University of Victoria Humanities Computing and Media Centre (HCMC). Martin ported the MOL project from its original PHP incarnation to a pure eXist database implementation in the fall of 2011. Since then, he has been lead programmer on the project and has also been responsible for maintaining the project schemas. He was a co-applicant on MoEML’s 2012 SSHRC Insight Grant.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of abstract

-

Conceptor

-

Encoder

-

Name Encoder

-

Post-conversion and Markup Editor

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

Contributions by this author

Martin D. Holmes is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Martin D. Holmes is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Shannon Kelley

Shannon Kelley is a MoEML Pedagogical Partner. She is an Assistant Professor of English at Fairfield University. Her teaching and research fields include Lyric Poetry, Literary Theory, Ecocriticism, Early Modern Culture, Science Studies, and Renaissance Drama. Her class will prepare encyclopedia entries on the gardens on the Agas map, including the Bear Garden.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Guest Editor

Contributions by this author

Shannon Kelley is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Edward Alleyn is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Charles II

Charles II King of England, Scotland, and Ireland

(b. 1630, d. 1685)King of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Edward III

Edward III King of England

(b. 12 November 1312, d. 21 June 1377)King of England and lord of Ireland, 1327—1377. Duke of Aquitaine, 1327—1360, and lord of Aquitaine, 1360—77. Son of Edward II and Isabella of France.Edward III is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth Tudor I Queen of England and Ireland

(b. 7 September 1533, d. 24 March 1603)Queen of England and Ireland.Elizabeth I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Henry VIII is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Prince Henry Frederick

Prince Henry Frederick Stuart

(b. 19 February 1594, d. 6 November 1612)Prince of Wales and eldest son of King James I and Queen Anne of Denmark. Brother of Charles I and Princess Elizabeth Stuart. Died of typhoid fever at the age of eighteen.Prince Henry Frederick is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Philip Henslowe is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Wenceslaus Hollar

(b. 1607, d. 1677)Bohemian etcher who in 1637 moved to London, where he etched a number of buildings and plans of the city.Wenceslaus Hollar is mentioned in the following documents:

-

James VI and I

King James Stuart VI and I

(b. 1566, d. 1625)King of Scotland, England, and Ireland.James VI and I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Ben Jonson is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Leland is mentioned in the following documents:

-

William Shakespeare is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Master Slender

Character in Wlliam Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor.Master Slender is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Stow is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Taylor is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Claes van Visscher

Cartographer. Drew a map of London in 1616.Claes van Visscher is mentioned in the following documents:

-

William Lily is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Stephen Gardiner

(d. 1555)Bishop of Winchester. Helped merge parish of St. Mary Magdalen and St. Margaret into the parish of St. Saviour.Stephen Gardiner is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Bagford, John

John Bagford

(b. between 1650 and 1651, d. in or after 5 May 1716)Bookseller and antiquary.Bagford, John is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Fluddie, Thomas is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Polsted, Henry is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Sadler, Ralph is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Payne, William

William Payne

Payne, William is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Magno, Alessandro is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Pride, Thomas is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Dudley, Robert

Robert Dudley Earl of Leicester

Earl of Leicester. Courtier and friend of Elizabeth I.Dudley, Robert is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Golding, Arthur is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Ovid is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Gloucester

Character in William Shakespeare’s King Lear.Gloucester is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Macbeth

Eponymous character in William Shakespeare’s Macbeth.Macbeth is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Anton van den Wyngaerde is mentioned in the following documents:

Locations

-

The Globe is mentioned in the following documents:

-

The Clink is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Southwark is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Bull Baiting is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Bankside is mentioned in the following documents:

-

The Thames is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Westminster is mentioned in the following documents:

-

The Hope

For information about the Hope, a modern map marking the site where the it once stood, and a walking tour that will take you to the site, visit the Shakespearean London Theatres (ShaLT) article on the Hope.The Hope is mentioned in the following documents:

Organizations

-

Fairfield University English 213 Fall 2014 Students

Student contributors enrolled in English 213: Shakespeare I at Fairfield University in the Fall 2014 session, working under the guest editorship of Shannon Kelley.-

Fairfield University English 213 Fall 2014 Student Group 1

Student contributors enrolled in English 213: Shakespeare I at Fairfield University in the Fall 2014 session, working under the guest editorship of Shannon Kelley.Student Contributors

-

Fairfield University English 213 Fall 2014 Student Group 2

Student contributors enrolled in English 213: Shakespeare I at Fairfield University in the Fall 2014 session, working under the guest editorship of Shannon Kelley.Student Contributors

-

Fairfield University English 213 Fall 2014 Student Group 3

Student contributors enrolled in English 213: Shakespeare I at Fairfield University in the Fall 2014 session, working under the guest editorship of Shannon Kelley.Student Contributors

-

Fairfield University English 213 Fall 2014 Student Group 4

Student contributors enrolled in English 213: Shakespeare I at Fairfield University in the Fall 2014 session, working under the guest editorship of Shannon Kelley.Student Contributors

-

Fairfield University English 213 Fall 2014 Student Group 5

Student contributors enrolled in English 213: Shakespeare I at Fairfield University in the Fall 2014 session, working under the guest editorship of Shannon Kelley.Student Contributors

-

Variant spellings

-

Documents using the spelling

Bear Gardens

-

Documents using the spelling

Beare garden

-

Documents using the spelling

Beare gardens

-

Documents using the spelling

beare Gardens

-

Documents using the spelling

Bearegardens

-

Documents using the spelling

Beere bayting h

-

Documents using the spelling

Garden

-

Documents using the spelling

le Beara yarde