The Wall

Significance

Those walles of stone,as they were described by John Stow in A Survey of London, encircled the City of London, shaping both the urban footprint of the city and its social practices (Stow). Originally built as a Roman fortification for the provincial city of Londinium in the second century C.E., the London Wall remained a material and spatial boundary for the city throughout the early modern period. Described by Stow as

high and great,the London Wall dominated the cityscape and spatial imaginations of Londoners for centuries. Increasingly, the eighteen-foot high wall created a pressurized constraint on the growing city; the various gates functioned as relief valves where development spilled out to occupy spaces

outside the wall.Various church names in London today, such as St. Botolph-without-Aldgate, still retain the designation of their location within or without the city wall and a major street along the wall’s route bears the name of London Wall.

Location

The London Wall started at the River Thames, near the eastern side of the White Tower in the Tower of London complex. From there, the wall ran north by northwest, crossing Tower Hill to Aldgate. At Aldgate it changed direction, running west by northwest to Bishopsgate. Continuing west from Bishopsgate, the wall began a long, almost straight stretch along the northern side of the city,

ending at a bastion that still stands in the Churchyard of St. Giles, Cripplegate. Here the wall turned south, running parallel to Monkwell Street and Noble Street, before making an irregular

jogto the west again. From there, the wall continued past Aldersgate before turning, just south of St. Bartholomew the Great, south toward the river, crossing Newgate Street and Ludgate Hill. From there, the exact course to the Thames is unknown, as the path of the Roman wall had been changed in the medieval era (Bell 23-24). In the later fourth-century C.E., the Romans extended the wall along the River Thames, a site of current archaeological interest (Smith), fully walling in the city. The riverside Roman wall, eroded by the elements, had collapsed by the twelfth-century. The last riverside portions of the wall were pulled down, with Thames Street laid out along its former course (Merrifield 222).

History

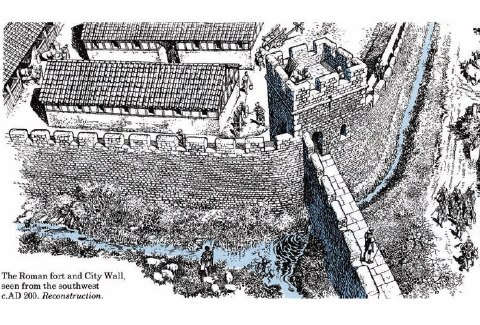

The Roman Wall

While Stow reports that the wall was built in 306 C.E., the building of the Roman Wall in London dates from much earlier. London was first founded as a trade port during the Roman Emperor Claudius’s conquests in Britain beginning in 43 C.E. After the native uprising against the occupying Roman force, led by Queen Boudica in 61 C.E., Londinium was burned and destroyed. At the time Boudica attacked, London had no encircling wall. The Romans subsequently rebuilt and expanded the city, including

a fortifying wall, as part of the development of the provincial capital for Roman

Britain. During the next thirty to forty years, the early settlement was rebuilt in the Roman

style, with new streets laid out and large public buildings constructed (Bell 17). Between 120 and 130 C.E., the wall was finished, an imposing defensive structure that became the greatest

manmade landmark of London through the early modern period—Stow’s

walles of stone.The area enclosed by the wall made London the largest Romano-British town, and the fifth largest town of the Roman Empire north of the Alps (Bell 17-18).

Medieval Era

After the Roman withdrawal in the early fifth-century, few records of London exist for the next few hundred years. Although St. Augustine arrived in Britain in 597 C.E., he made little mention of London. The next historical mention of the Roman Wall appears in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, when Alfred the Great drove the Danes from London (c. 871-872 C.E.) and ordered the restoration of the city and its defenses (Bell 42-43).

In 1080, William the Conqueror began building the White Tower along the Roman Wall, using one of its towers or bastions for its base, thus establishing the Tower of London complex. Later construction under Henry III, begun around 1238 C.E. and continued by Edward I, saw the enlargement of the Tower of London and the demolition of that segment of the Roman Wall to make space for new defensive curtain walls and a moat (Bell 45).

By 1276, the Order of Dominican Friars had settled into the district that is still known today as Blackfriars. At this location, they built a church and convent house, but their home was outside

of the wall. However, these friars enjoyed such favour and prestige that, in 1282, they were given permission from Edward I to pull down the wall near their site and rebuild the wall to enclose their religious

house. This medieval portion of the wall forms the irregular jog along the western

end of the wall (Bell 46-47; Stow). A continuous structure from the Tower to Blackfriars, the Roman Wall stood until it was cleared away in the eighteenth century. For 1600 years, London was a walled city.

Materials

Because the wall had an extensive history of being rebuilt and reinforced, the materials

that made up the wall varied. An imposing eighteen feet high, the majority of the

wall was built of Kentish rag-stone most likely harvested in the Maidstone district

in Kent. The wall was originally built on a foundation constructed of flints and puddled

clay often mixed with broken pieces of rag-stone. The external base of the wall, or

the plinth, contains material made primarily of sandstone, also believed to be of

Kentish origin. The base was then reinforced with a triple layer of brick. The stone

of both the interior and exterior faces of the wall is coarse and set in a hard, white

mortar (Cook 1-7). To further protect the integrity of the wall and to keep the construction level,

double or triple rows of flat, red tiles were laid for every four to five courses

of stone (English Heritage). Additional measures were taken as the wall aged in order to reinforce its outer

and inner defenses. Originally, the wall was supplemented by an external ditch, ranging

from about 10.5 to 15 feet from the base. An earthen bank was built up against it,

and further defensive techniques were put in place in the form of additional, semi-circular

bastions on the wall’s exterior (Cook 1-7; Stow).

Literary Significance

In addition to its functions of security and boundary marking, the wall also served

governmental monitoring functions, controlling ingress and egress, and, as such, registered

in the literary imagination of London writers.

Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer lived in apartments above Aldgate from 1374 to 1386. Chaucer was witness to the spectrum of life passing in and out of the gates, writing two

of his works, The Parliament of Fowles and The House of Fame, while residing at the gate’s entrance (Benson xvi-xviii; Lyons). He may have there witnessed the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, where a tumultuous mob pressed its way through the city gate (Lyons), physically and symbolically laying claim to the elite space of London. In the Nun’s Priest Tale of The Canterbury Tales, Chaucer makes an oblique reference to the Peasants’ Revolt (Astell), comparing the uproar of the barnyard at the fox’s intrusion to the rabble of the

crowd streaming in through Aldgate under the leadership of Jack Straw:

(Chaucer 3393-3396)So hydous was the noyse, a benedictee!Certes, he jakke straw and his meyneeNe made nevere shoutes half so shrilleWhan that they wolden any flemyng kille.

William Shakespeare

While Shakespeare is primarily associated with urban London life, upon first coming to London he lived outside the wall in Shoreditch (Aubrey 97), a town known for its crime-ridden back alleys. The site of the first purpose-built

theatres, the Theatre (built in 1576) and the Curtain (built in 1577), Shoreditch became the

Bohemian haunt of Elizabethan London(Nicholl 39). Shoreditch lies just north of Bishopsgate, one of the major entrances into the City of London. Tax records of the time show that Shakespeare’s first recorded address inside the wall was in the north-eastern area of London, near Bishopsgate (Wood 131). In the Parish of St. Helen’s in Bishopsgate stood many inn yards such as the Four Swans Inn and the Black Bull Inn, where wooden galleries, three stories high, could be rented for a penny a night. Nearby lodgings would naturally have been a draw for the young playwright, as the inn yards were frequented by artists, poets, and actors. This area of London was within walking distance, approximately a mile away, to The Theatre in Shoreditch where Shakespeare continued to work.

The distinction between the relative order and protection within the walls and the

lack thereof for those consigned to live outside of the city boundaries formed part

of Shakespeare’s daily life as he passed through Bishopsgate from his residence inside the city wall to the Theatre, beyond the city gate. Outside the wall, there was a different world: over three

hundred inns and brothels could be found outside the city walls, along with bull and

bear baiting rings, and skittle and bowling alleys (Wood 186). Also just outside of Bishopsgate was the original site of the Bethlehem Hospital, which became known as Bedlam, a mental asylum. Walking along the streets there at night, one would have likely

heard the howling of dogs, the roaring of chained bears, and even screams from patients

at Bedlam Asylum.

Shakespeare subsequently moved to the quieter environs of Silver Street, near Cripplegate, where he was a lodger in a house at the corner of Silver Street and Monkwell Street (identified as Muggle Street on the Agas map) (Nicholl 4-6). Though farther from the boisterous world of the playgoers, Shakespeare’s daily life at his Silver Street residence provided a constant reminder of the spatial and social divisions formed

by the wall: his lodgings were located just a short half-block from the section of

the Wall that bounded Noble Street, marking the western boundary of the city.

The spatial and social barriers created by the London Wall find expression in Shakespeare’s plays in imagery of division and exclusion. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, for example, the physical wall that separates the lovers Pyramus and Thisbe in the play-within-the-play is humorously embodied by the actor Snout. The inanimate materiality of the wall, observes Alexander Leggatt,

achieves human qualities(Leggatt 203).

O wicked Wall through whom I see no bliss! / Cursed be thy stones for thus deceiving me!(Shakespeare 5.1.175-176), cries Pyramus. The wall separates the two lovers, causing the melodramatic strife of the rustics’ drama. But Pyramus’s dying words suggest the possibility for social redemption:

the wall is down that parted their fathers(Shakespeare 5.1.301). For early modern playgoers, this scene might have evoked the spatial and social boundaries imposed by the rough stones of the ancient Roman Wall in London.

The London Wall, as the primary remaining artifact of Roman London, may well have inspired Shakespeare to think about the connections between his early modern society and Roman times.

Fully one third of Shakespeare’s plays are set in Italy, Rome, or the Mediterranean, and his play Cymbeline takes up the lore of the Roman War campaign. As Gail Kern Paster has noted,

Shakespeare is particularly drawn to those moments in the Roman past which brought the internal order of the city to a point of critical change when one kind of city was giving way to another(Paster 58). Like the Rome depicted in plays like Coriolanus and Julius Caesar, early modern London was indeed such a city undergoing critical changes due to urbanization, immigration, and the emergence of an increasingly powerful mercantile class.

John Stow’s Survey of London

As in Shakespeare’s work, Stow’s Survey of London gives evidence of

the ubiquitous presence of Rome in Elizabethan culture(Miola 11), the lingering trace of Roman culture in defining the city’s boundaries, and the sense of continuity with the original builders of the wall. Stow repeatedly regards the Romans with admiration, claiming the Britons were unskilled,

not able to defend themselvesand thus sent word to Rome so that the

Romaines woulde rescue them out of the hands of their enemies(Stow). Stow writes approvingly of the Romans’ impact on London such that, when describing the distance between the wall’s gates, he uses the Roman unit of measurement known as a

perch.There was both admiration as well as

ambivalence inherent in Britain’s emulation of Rome(Kahn 161), as evidenced by how the Agas map appropriates the language of Roman imperialism and downplays Britain’s former role as a colonized territory.

The Wall on the Agas Map

The wall of the

ancient and famous City of Londonis depicted on the Agas map as a significant dividing line, keeping the inner city contained and rural practices strictly outside the wall. Strikingly, there are no human figures depicted within the enclosure of the wall. In this way, the urban space of the map adopts emerging cartographic practices of Ptolemaic-based mapping, emphasizing place names and linearity, while the surrounding countryside displays ethnographic practices of the medieval mappa mundi (Roland 128) as well as early modern landscape representations. The difference in shading between the top of the wall and the bottom on the Agas map suggests keen attentiveness to the realistic depiction of the multiple materials used to erect and maintain the wall. The main gates that allow passage in and out of the city, and the bastions in between, are prominently featured on the map.

There are two cartouches engraved on the Agas map, one poetic and the other a laudatory

introductionto the City of London. The two cartouches, located near the bottom of the map, connect London to a mythological Roman heritage, each proudly stating that the city was

founded by Brute the Trojanwho, according to Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae, had come from Troy to claim a new land for himself and his people. The text of the prose cartouche emphasizes the fact that London was bounded: it is

compaſſed with corne & paſture groundand

incloſed with the river of Thames.The poetic cartouche, in contrast, points to King Lud’s increasing of the bounds of the city. On the map, many buildings push up against the very perimeter of the wall, enacting this process of exceeding the Roman-built boundaries. Compared to the openness of the countryside, London inside the city walls is compact, made up only of largely contiguous buildings. The people working the land, playing, fighting, or navigating boats along the Thames serve as a pastoral contrast to the crowded built environment inside the wall.

The cartouches not only proclaim London’s imperial history but also praise its abundant natural resources: London’s

very good soyle,the Thames’s provision of

all kind of fresh water-fishand a navigation system that

bringeth abundance of commodities from all parts of the world.By incorporating Geoffrey of Monmouth’s myth of the founding of London, referenced in later works from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight to Holinshed’s Chronicles, the Agas map makes a claim that London, with its ample resources and prime location, is the global successor to the legacy of Rome. The decorative banner at the top of the map reinforces this message, by proclaiming the Latin title

Civitas Londinumto be the subject of the map.

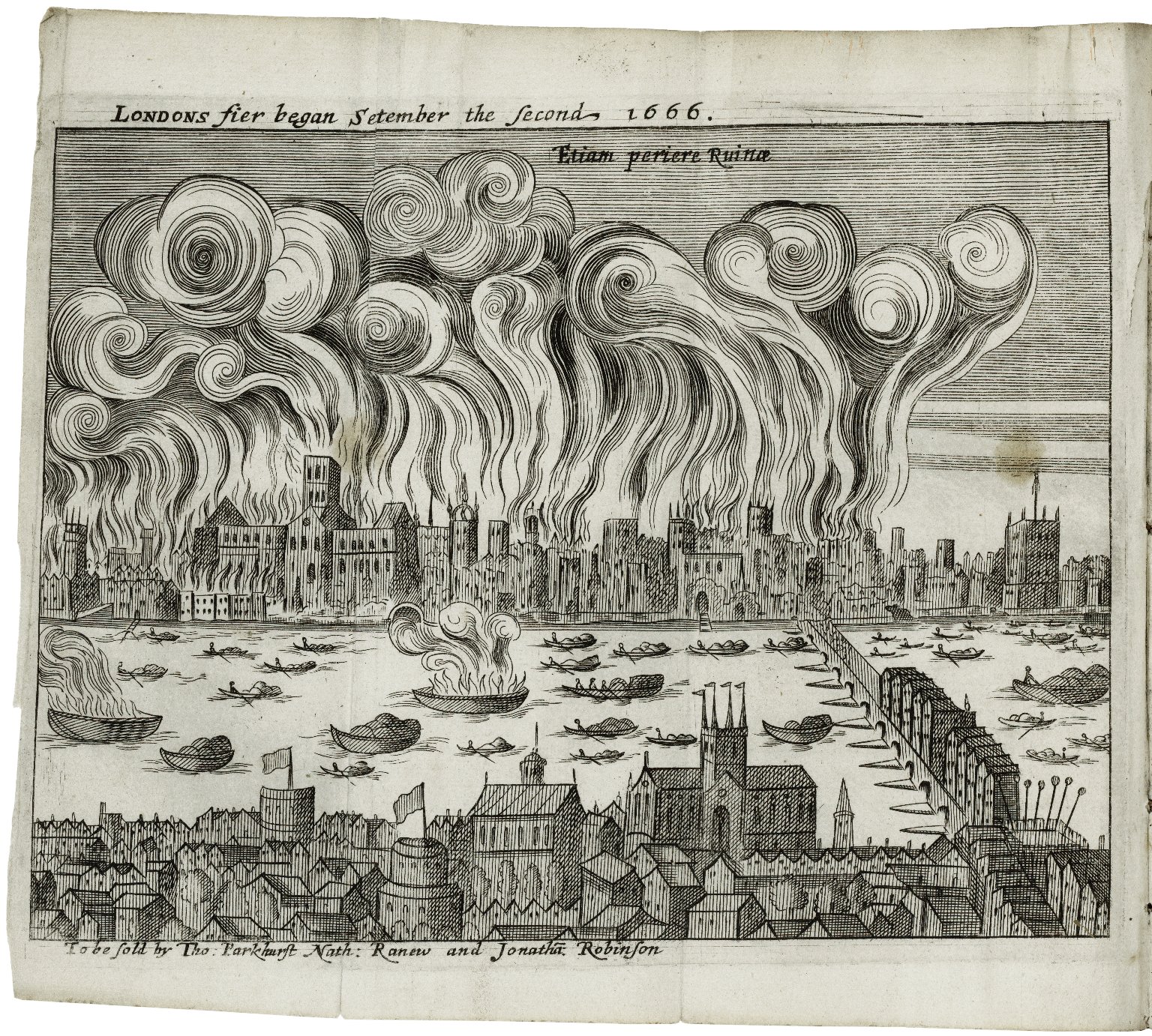

Great Fire of 1666

Londons Fier began Setember the Second 1666(Samuel Rolle). Image courtesy of the Folger Digital Image Collection.

By the time the Agas map was completed in 1561, London was pushing past the confines of the wall. But the Great Fire of 1666 provided the definitive blow to the definition of the city as primarily enclosed

within the London Wall.1 There had long been warnings of the potential for a destructive fire due to London’s narrow streets, thatched roofs, and strong east winds, all exacerbated by the unusually

hot, dry summer of 1666. London was built mainly out of timber construction and the summer’s drought had drastically

depleted the city’s water reserves (Robinson). Due to the high death rate from the plague, fires were the last thing on Londoner’s

minds, the warnings were largely disregarded, and few precautions were taken. In the

late hours of 2 September 1666, a spark in a baker’s unextinguished oven set the Great Fire in motion: the fire

spread quickly, jumping over twenty houses at a time while gathering force from combustibles

such as hemp, oil, tallow, hay, timber, coal, and spirits. Citizens began tearing

down buildings, desperately hoping to widen the gap between buildings and deprive

the fire of further fuel. Four days after the fire began, however, 13,200 houses,

84 churches, and 44 company halls had been destroyed, along with a third of London Bridge. Fewer than ten lives were lost, but 373 acres of land, approximately 80% of the

interior walled London, had burned (

Great Fire of London Map). Almost 100,000 people (1/6 of London’s population) became homeless (Robinson). Most of these homeless camped outside the walls of London; due to soaring rent rates from lack of housing, most eventually moved to other villages or found accommodation outside the city walls. Wealthier families began building larger residences, claiming valuable space within the city.

A Plan of the City and Liberties of London; Shewing the Extent of the Dreadful Conflagration in the Year 1666(Wenceslaus Hollar). Image courtesy of Map and Plan Collection Online (MAPCO).

The fire irrevocably altered the spatial constructs of London: in October 1666, Charles II and the City appointed Commissioners to preside over the rebuilding of London. The gates damaged by the Great Fire, Ludgate, Newgate, and Moorgate, were rebuilt by the end of the 1670s (Hughes n.p.). In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the gates, now superfluous in regulating

egress and ingress, were removed (Schofield). Surviving sections of the wall remain visible in London today and parts of the riverside wall can be seen within the Tower of London (

Londinium Today: Riverside Wall). Near the current site of the Museum of London, sections of the wall and the ruins of one of the bastions still stand (

Londinium Today: City Wall and Gates). Neighborhoods around London still bear the names of the historic gates, providing a linguistic trace of the initial plan of the City of London.

By the time the Agas map was created, the city had rebuilt and repurposed the Wall, re-territorializing the city’s prior position as a colonized province of Rome. Sigmund

Freud suggested a

phantasyusing the city of Rome as an analogy for the complexity of human memory in which

all the earlier phases of development continue to exist alongside the latest one(Freud 18).

If we want to represent historical sequence in spatial terms,Freud suggested,

we can only do it by juxtaposition in space(Freud 19). While Freud ultimately rejects this pictorial model of human memory, this juxtaposition in space of the Roman wall amid the development of the city, asserted a visible, if fragmentary, trace of London’s Roman past as part of early modern English culture. Remnants of the past remain within the wall’s multiple layers and fragmentary remains, often side-by-side with contemporary streets and buildings, revealing a history of inspiration, exclusion, and control, and continuing to define the geographical and cultural space of modern day London.

Notes

- See

The Great Fire of London

for more information about this event.↑

References

-

Citation

Astell, Ann.The Peasants’ Revolt: Cock-crow in Gower and Chaucer.

Essays in Medieval Studies 10 (1993): 53-61.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Bell, Walter G., F. Cottril, and Charles Spon. London Wall: Through Eighteen Centuries, A History of the Ancient Town Wall of the City of London with a Survey of the Existing Remains. London and Wisbech: Balding and Mansell, 1937.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer. Ed. F.N. Robinson. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1957. Reprint. Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse. University of Michigan Library. Open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Cook, Norman. Old Wall and The City of London. London: Corporation of London, 1951.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Freud, Sigmund. Civilization and Its Discontents.Trans. and ed. James Strachey. New York: W.W. Norton, 1961.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Hughes, E.H. The Gates of London: An Illustrated Survey. London: The Lion and Unicorn Press, 1953. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Kahn, Coppélia. Roman Shakespeare: Warriors, Wounds, and Women. Feminist Readings of Shakespeare. New York and London: Routledge, 1997.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Leggatt, Alexander. Citizen Comedy in the Age of Shakespeare. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1973.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Merrifield, Ralph. London, City of Romans.Berkeley: U of California P, 1983.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Miola, Robert S. Shakespeare’s Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1983.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Nicholl, Charles. The Lodger Shakespeare: His Life on Silver Street. New York: Viking, 2007.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Paster, Gail Kern. The Idea of the City in the Age of Shakespeare. Athens: U of Georgia P, 1985.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Roland, Meg.After Poyetes and Astronomyers: English Geographical Thought and Early English Print.

Mapping Medieval Geographies: Geographical Encounters in the Latin West and Beyond, 300–1600. Ed. Keith Lilley. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2014. 127-151.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Schofield, John.London After the Great Fire.

BBC History. British Broadcasting Corporation, 2011. Open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Shakespeare, William. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Ed. Suzanne Westfall. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Stow, John. A Survey of London. Reprinted from the Text of 1603. Ed. Charles Lethbridge Kingsford. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1908. Reprint. British History Online. Subscription. [Kingsford edition, courtesy of The Centre for Metropolitan History. Articles written 2011 or later cite from this searchable transcription. In the in-text parenthetical reference (Stow; BHO), click on BHO to go directly to the page containing the quotation or source.]This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Wood, Michael. In Search of Shakespeare. London: BBC Books, 2003.This item is cited in the following documents:

Cite this page

MLA citation

, and .

The Wall.The Map of Early Modern London, edited by , U of Victoria, 20 Jun. 2018, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/WALL2.htm.

Chicago citation

, and .

The Wall.The Map of Early Modern London. Ed. . Victoria: University of Victoria. Accessed June 20, 2018. http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/WALL2.htm.

APA citation

, & . 2018. The Wall. In (Ed), The Map of Early Modern London. Victoria: University of Victoria. Retrieved from http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/WALL2.htm.

RIS file (for RefMan, EndNote etc.)

Provider: University of Victoria Database: The Map of Early Modern London Content: text/plain; charset="utf-8" TY - ELEC A1 - Marylhurst University English 386 Fall 2014 Student Group 1 A1 - Marylhurst University English 386 Fall 2014 Student Group 2 ED - Jenstad, Janelle T1 - The Wall T2 - The Map of Early Modern London PY - 2018 DA - 2018/06/20 CY - Victoria PB - University of Victoria LA - English UR - http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/WALL2.htm UR - http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/xml/standalone/WALL2.xml ER -

RefWorks

RT Web Page SR Electronic(1) A1 Marylhurst University English 386 Fall 2014 Student Group 1 A1 Marylhurst University English 386 Fall 2014 Student Group 2 A6 Jenstad, Janelle T1 The Wall T2 The Map of Early Modern London WP 2018 FD 2018/06/20 RD 2018/06/20 PP Victoria PB University of Victoria LA English OL English LK http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/WALL2.htm

TEI citation

<bibl type="mla"><author><name ref="#MAUN1_1" type="org">Marylhurst University English 386 Fall 2014 Student Group 1</name></author>, and <author><name ref="#MAUN1_2" type="org">Marylhurst University English 386 Fall 2014 Student Group 2</name></author>. <title level="a">The Wall</title>. <title level="m">The Map of Early Modern London</title>, edited by <editor><name ref="#JENS1"><forename>Janelle</forename> <surname>Jenstad</surname></name></editor>, <publisher>U of Victoria</publisher>, <date when="2018-06-20">20 Jun. 2018</date>, <ref target="http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/WALL2.htm">mapoflondon.uvic.ca/WALL2.htm</ref>.</bibl>Personography

-

Janelle Jenstad

JJ

Janelle Jenstad, associate professor in the department of English at the University of Victoria, is the general editor and coordinator of The Map of Early Modern London. She is also the assistant coordinating editor of Internet Shakespeare Editions. She has taught at Queen’s University, the Summer Academy at the Stratford Festival, the University of Windsor, and the University of Victoria. Her articles have appeared in the Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Early Modern Literary Studies, Elizabethan Theatre, Shakespeare Bulletin: A Journal of Performance Criticism, and The Silver Society Journal. Her book chapters have appeared (or will appear) in Performing Maternity in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2007), Approaches to Teaching Othello (Modern Language Association, 2005), Shakespeare, Language and the Stage, The Fifth Wall: Approaches to Shakespeare from Criticism, Performance and Theatre Studies (Arden/Thomson Learning, 2005), Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society (Brill, 2004), New Directions in the Geohumanities: Art, Text, and History at the Edge of Place (Routledge, 2011), and Teaching Early Modern English Literature from the Archives (MLA, forthcoming). She is currently working on an edition of The Merchant of Venice for ISE and Broadview P. She lectures regularly on London studies, digital humanities, and on Shakespeare in performance.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Stub

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

Author of Textual Introduction

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Course Instructor

-

Course Supervisor

-

Course supervisor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Structure and Toponyms)

-

Final Markup Editor

-

GIS Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Modern)

-

Geographical Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Main Transcriber

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Name Encoder

-

Peer Reviewer

-

Primary Author

-

Project Director

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Reviser

-

Second Author

-

Second Encoder

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Janelle Jenstad is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Janelle Jenstad is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Tye Landels-Gruenewald

TLG

Research assistant, 2013-15, and data manager, 2015 to present. Tye completed his undergraduate honours degree in English at the University of Victoria in 2015.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

MoEML Researcher

-

Name Encoder

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

Contributions by this author

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kim McLean-Fiander

KMF

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach, 2015–present; Associate Project Director, 2015–present; Assistant Project Director, 2013-2014; MoEML Research Fellow, 2013. Kim McLean-Fiander comes to The Map of Early Modern London from the Cultures of Knowledge digital humanities project at the University of Oxford, where she was the editor of Early Modern Letters Online, an open-access union catalogue and editorial interface for correspondence from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. She is currently Co-Director of a sister project to EMLO called Women’s Early Modern Letters Online (WEMLO). In the past, she held an internship with the curator of manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library, completed a doctorate at Oxford on paratext and early modern women writers, and worked a number of years for the Bodleian Libraries and as a freelance editor. She has a passion for rare books and manuscripts as social and material artifacts, and is interested in the development of digital resources that will improve access to these materials while ensuring their ongoing preservation and conservation. An avid traveler, Kim has always loved both London and maps, and so is particularly delighted to be able to bring her early modern scholarly expertise to bear on the MoEML project.Roles played in the project

-

Associate Project Director

-

Author

-

Author of MoEML Introduction

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Contributor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Contributor

-

Data Manager

-

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (People)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Managing Editor

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Research Fellow

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Second Author

-

Secondary Author

-

Secondary Editor

-

Toponymist

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Kim McLean-Fiander is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Kim McLean-Fiander is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Joey Takeda

JT

Programmer, 2018-present; Junior Programmer, 2015 to 2017; Research Assistant, 2014 to 2017. Joey Takeda is an MA student at the University of British Columbia in the Department of English (Science and Technology research stream). He completed his BA honours in English (with a minor in Women’s Studies) at the University of Victoria in 2016. His primary research interests include diasporic and indigenous Canadian and American literature, critical theory, cultural studies, and the digital humanities.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Stub

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Date Encoder

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Bibliography)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Agas)

-

Junior Programmer

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Encoder

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Second Author

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Editor

Contributions by this author

Joey Takeda is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Joey Takeda is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Martin D. Holmes

MDH

Programmer at the University of Victoria Humanities Computing and Media Centre (HCMC). Martin ported the MOL project from its original PHP incarnation to a pure eXist database implementation in the fall of 2011. Since then, he has been lead programmer on the project and has also been responsible for maintaining the project schemas. He was a co-applicant on MoEML’s 2012 SSHRC Insight Grant.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of abstract

-

Conceptor

-

Encoder

-

Name Encoder

-

Post-conversion and Markup Editor

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

Contributions by this author

Martin D. Holmes is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Martin D. Holmes is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Meg Roland

Meg Roland is a MoEML Pedagogical Partner. She is Associate Professor and Chair of Literature and Art at the Marylhurst University.Roles played in the project

-

Guest Editor

-

Researcher

Meg Roland is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great King of the West Saxons and the Anglo-Saxons

(b. between 848 and 849, d. 899)King of the West Saxons and the Anglo-Saxons.Alfred the Great is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Charles II

Charles II King of England, Scotland, and Ireland

(b. 1630, d. 1685)King of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Geoffrey Chaucer is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Edward I

Edward I King of England

(b. between 17 June 1239 and 18 June 1239, d. in or before 27 October 1307)King of England.Edward I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Raphael Holinshed

(b. 1525, d. 1580)Historian and principal author of the Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Raphael Holinshed is mentioned in the following documents:

-

King Lud is mentioned in the following documents:

-

William Shakespeare is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Stow is mentioned in the following documents:

-

William I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

St. Augustine of Canterbury

Saint Augustine of Canterbury

(d. 26 May 604)Archbishop of Canterbury and first official missionary to the Anglo-Saxons in Britain. Buried in the Church of St. Peter and St. Paul in Canterbury, Kent.St. Augustine of Canterbury is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Jack Straw

Leader of the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381.Jack Straw is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth Bishop of St. Asaph

(d. between 1154? and 1155?)Bishop of St. Asaph and historian.Geoffrey of Monmouth is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Claudius is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Pyramus

Lover from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. He is played by Nick Bottom in the play-within-the-play in William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.Pyramus is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thisbe

Lover from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. She is played by Francis Flute in the play-within-the-play in William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.Thisbe is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Tom Snout

Mechanical in William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.Tom Snout is mentioned in the following documents:

Locations

-

St. Botolph (Aldgate)

St. Botolph, Aldgate was a parish church near Aldgate at the junction of Aldgate Street and Houndsditch. It was located in Portsoken Ward on the north side of Aldgate Street. Stow notes that theChurch hath beene lately new builded at the speciall charges of the Priors of the holy Trinitie

before the Priory was dissolved in 1531 (Stow).St. Botolph (Aldgate) is mentioned in the following documents:

-

The Thames is mentioned in the following documents:

-

White Tower is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Tower of London is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Tower Hill

Tower Hill was a large area of open ground north and west of the Tower of London. It is most famous as a place of execution; there was a permanent scaffold and gallows on the hillfor the execution of such Traytors or Transgressors, as are deliuered out of the Tower, or otherwise to the Shiriffes of London

(Stow).Tower Hill is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Aldgate

Aldgate was the easternmost gate into the walled city. The nameAldgate

is thought to come from one of four sources: Æst geat meaningEastern gate

(Ekwall 36), Alegate from the Old English ealu meaningale,

Aelgate from the Saxon meaningpublic gate

oropen to all,

or Aeldgate meaningold gate

(Bebbington 20–1).Aldgate is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Bishopsgate is mentioned in the following documents:

-

St. Giles Churchyard (Cripplegate) is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Monkwell Street is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Noble Street

Noble Street ran north-south between Maiden Lane in the south and Silver Street in the north. It isall of Aldersgate street ward

(Stow). On the Agas map, it is labelled asNoble Str.

and is depicted as having a right-hand curve at its north end, perhaps due to an offshoot of the London Wall.Noble Street is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Aldersgate is mentioned in the following documents:

-

St. Bartholomew the Great is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Newgate Street is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Fleet Hill or Ludgate Hill is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thames Street

Thames Street was the longest street in early modern London, running east-west from the ditch around the Tower of London in the east to St. Andrew’s Hill and Puddle Wharf in the west, almost the complete span of the city within the walls.Thames Street is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Blackfriars Precinct is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Shoreditch is mentioned in the following documents:

-

The Theatre is mentioned in the following documents:

-

The Curtain

In 1577, the Curtain, a second purpose-built London playhouse arose in Shoreditch, just north of the City of London. The Curtain, a polygonal amphitheatre, became a major venue for theatrical and other entertainments until at least 1622 and perhaps as late as 1698. Most major playing companies, including the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, the Queen’s Men, and Prince Charles’s Men, played there. It is the likely site for the premiere of Shakespeare’s plays Romeo and Juliet and Henry V.The Curtain is mentioned in the following documents:

-

St. Helen (Parish) is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Four Swans Inn is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Black Bull Inn (Bishopsgate Street)

For information about the Black Bull Inn, Bishopsgate Street, a modern map marking the site where the it once stood, and a walking tour that will take you to the site, visit the Shakespearean London Theatres (ShaLT) article on Black Bull Inn, Bishopsgate Street.Black Bull Inn (Bishopsgate Street) is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Bethlehem Hospital

Although its name evokes the pandemonium of the archetypal madhouse, Bethlehem (Bethlem, Bedlam) Hospital was not always an asylum. As John Stow tells us, Saint Mary of Bethlehem began as aPriorie of Cannons with brethren and sisters,

founded in 1247 by Simon Fitzmary,one of the Sheriffes of London

(1.164). We know from Stow’s Survey that the hospital, part of Bishopsgate ward (without), resided on the west side of Bishopsgate street, just north of St. Botolph’s church (2.73; 1.165).Bethlehem Hospital is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Silver Street

Silver Street was a small but historically significant street that ran east-west, emerging out of Noble Street in the west and merging into Addle Street in the east. Monkwell Street (labelledMuggle St.

on the Agas map) lay to the north of Silver Street and seems to have marked its westernmost point, and Little Wood Street, also to the north, marked its easternmost point. Silver Street ran through Cripplegate Ward and Farringdon Ward Within. It is labelled asSyluer Str.

on the Agas map and is drawn correctly. Perhaps the most noteworthy historical fact about Silver Street is that it was the location of one of the houses in which William Shakespeare dwelled during his time in London.Silver Street is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Cripplegate

Cripplegate was one of the original gates in the city wall (Weinreb, Hibbert, Keay, and Keay 221; Harben). It was the northern gate of a large fortress that occupied the northwestern corner of the Roman city.Cripplegate is mentioned in the following documents:

-

London Stone

London Stone was, literally, a stone that stood on the south side of what is now Cannon Street (formerly Candlewick Street). Probably Roman in origin, it is one of London’s oldest relics. On the Agas map, it is visible as a small rectangle between Saint Swithin’s Lane and Walbrook, just below thend

consonant cluster in the labelLondonston.

London Stone is mentioned in the following documents:

-

London Bridge

From the time the first wooden bridge in London was built by the Romans in 52 CE until 1729 when Putney Bridge opened, London Bridge was the only bridge across the Thames in London. During this time, several structures were built upon the bridge, though many were either dismantled or fell apart. John Stow’s 1598 A Survey of London claims that the contemporary version of the bridge was already outdated by 994, likely due to the bridge’s wooden construction (Stow 1:21).London Bridge is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Ludgate is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Newgate is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Moorgate is mentioned in the following documents:

Organizations

-

The Order of Dominican Friars

The namesake of the Blackfriars Precinct, The Order of the Dominican Friars, or theBlack Friars

(named for their customaryblack mantle and hood

), were an order of mendicant friars founded by Saint Dominic in France in 1216 (Dominican Order). Intent on spreading Catholicism, Saint Dominic sent members of his order to England, where no later than 1247, the order had bases in Oxford and London (Jarrett 2-3). In the wake of the Reformation, members of the order fled the country or remained in England andeither drifted into poverty, or else entered the ranks of the secular clergy

(Jarrett 169).This organization is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Marylhurst University English 386 Fall 2014 Students

-

Marylhurst University English 386 Fall 2014 Student Group 1

Student contributors enrolled in English 386: The Eternal City: Rome in the Western Literary Imagination at Marylhurst University in the Summer 2014 session, working under the guest editorship of Meg Roland.Student Contributors

-

Marylhurst University English 386 Fall 2014 Student Group 2

Student contributors enrolled in English 386: The Eternal City: Rome in the Western Literary Imagination at Marylhurst University in the Summer 2014 session, working under the guest editorship of Meg Roland.Student Contributors

-

Variant spellings

-

Documents using the spelling

city wall

-

Documents using the spelling

City Wall and Ditch

-

Documents using the spelling

city walls

-

Documents using the spelling

London wall

-

Documents using the spelling

London Wall

-

Documents using the spelling

Roman Wall

-

Documents using the spelling

The Wall

-

Documents using the spelling

wal

-

Documents using the spelling

Wall

-

Documents using the spelling

wall

-

Documents using the spelling

wall of London

-

Documents using the spelling

wall of the city

-

Documents using the spelling

walles

-

Documents using the spelling

Walles of London

-

Documents using the spelling

Walls

-

Documents using the spelling

Wals of London

-

Documents using the spelling

wals of this Citie