Critical Introduction

Thomas Middleton wrote The Triumphs of Truth in 1613, to honour

the Lord Mayor of the same name, Sir Thomas Middleton, Grocer.

The Triumphs of Truth was

the most expensive mayoral pageant of the Renaissance,and, despite the propaganda that is construed negatively today, it was arguably Middleton’s

finest(Bergeron Civic 179).

The Triumphs of Truth is what Margot Heinemann calls

a sustained moral allegory(Heinemann 127). It relies on theme and symbolism rather than plot, and the theme that is

sustainedthroughout the pageant is

Truth prevails over Error.Thomas Middleton also makes use of allegorical characters, such as Truth, Zeal, and Error, and costumes them emblematically so that the members of the civic audience will be able to know who each character is, even if they cannot hear the pageant. David M. Bergeron praises Middleton’s descriptions of the allegorical characters. He says,

No other pageant-dramatist [. . .] gives greater evidence of understanding the traditional iconographical presentation of allegorical figures. It is not merely a portrait, however, for it has a dramatic function: to sharpen the contrast between good and evil(Bergeron Civic 182). Lawrence Manley says that

Middleton’s pageants, sponsored by such Puritan-dominated companies as the Grocers or the Skinners, were especially frank in their allusions to contemporary vices threatening the City rulers(Manley 282). In The Triumphs of Truth, Middleton deals explicitly with bribery and corruption, which is atypical for the Lord Mayor’s Show (Heinemann 125), through the character of Error. Error, typifying how not to rule as Lord Mayor, promises to teach the Lord Mayor how to

cast mists,and to bring the Lord Mayor bribes.

The Lord Mayor’s Show was unlike a stage play in that the pageant was

peripatetic, and no one member of the audience saw it from start to

finish. There was a need to write in a simple style and incorporate

repetitive action (like the struggle between Error and Truth with the

mist), so that the

moralor

themewould be obvious to a person who had not seen or heard what came before. The

cause of dramatic unityis strengthened in The Triumphs of Truth by the

movement throughout the processional of all the devices; thus the audience at almost any point has a chance to understand the dramatic action(Bergeron Civic 186).

Unity in The Triumphs of Truth is also achieved by using simple imagery -- light to represent

good and dark to represent evil (181). Truth’s Angel is wearing

white silkwhich is

powdered with stars of goldand Truth is adorned in

white satin,and wears a

diadem of stars,while Error wears

ash-colour silke.

Taking the conflict of the light/dark imagery a step further are the

Moors. The King of the Moors makes reference to his dark face, but

states that

Truth in [his] soul sets up the light of grace.It seems

that this King of Moors and his queen had been converted to Christianity by English merchants traveling in their land(183), and they rejoice in their new found religion. As well as setting up a hierarchy with

Goodover

Evil,in this scene of The Triumphs of Truth a hierarchy is created with

Christianover

Pagan.In this sense, The Triumphs of Truth is justifying the Christianization of far off lands, and promoting trade as a method to do so (Knowles 168).

Textual Introduction

This text is based on a collation of the two editions of The Triumphs of Truth. There are three surviving copies of the first edition (STC 17903), and seven copies

of the second (STC 17904).

This edition is based on the British Museum copies of both editions.

The two original editions were printed by Nicholas Okes in 1613. The central difference between the

two editions of the pageant is the inclusion in the second edition of the entertainment

at

Amwell-Head on Michaelmas Day; it is absent from

the first edition. The second edition has a new title page, reflecting

the inclusion of the new section of text. The second edition corrects

some textual errors that appeared in the first edition. The type does

not appear to have been reset between the two editions, however; other

than the compositor’s corrections in the second edition, the two texts

are identical.

Unlilke other MoEML texts, this diplomatic transcription modernizes the u/v and i/j typographical conventions.

The only other change that has been made has been

the distinction between then and than. In the original text it

appears as then almost exclusively. Where appropriate, it has been

changed to than. This edition also corrects obvious compositional

errors, noting these corrections in editorial notes.

Middleton wrote The Triumphs of Truth at a time when pageants were made not only as entertainment,

but also as literary texts. The printing, and then reprinting of The Triumphs of Truth, suggests that it was not

only a successful pageant, but was also a successful literary

achievement.

The Route

-

The Lord Mayor begins the day at Guildhall.

-

Musicians are already playing as the Lord Mayor makes his way from Guildhall to Soper-Lane End. After a song, the Lord Mayor is welcomed with a trumpet flourish. London greets him and makes her first speech.

-

The Lord Mayor, his company, and the waits of the city (a small body of wind instrumentalists maintained by a city), are led down to the banks of the Thames, where they see the five islands for the first time.

-

The Lord Mayor then proceeds by water to Westminster where he swears his Oath of Mayoralty.

-

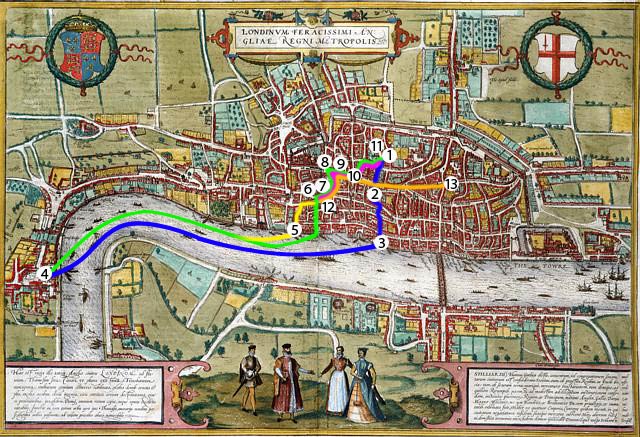

The Lord Mayor returns to the City and is met by Truth’s Angel and Zeal at Baynard’s Castle. Lawrence Manley suggests that landing at Baynard’s Castle is a deviation from the standard route of the Lord Mayor’s show. In his Literature and Culture in Early Modern London, he shows the route using Paul’s Stairs instead (Manley 226-27). The green line on the map represents the route that Manley suggests was standard, and the yellow line represents the route that The Triumphs of Truth took.

-

Truth’s Angel and Zeal accompany the Lord Mayor to Paul’s Chain, where he is

assaulted

by Error and his champion, Envy. Truth arrives withher celestial handmaidens, the Graces and Virtues

to give the Lord Mayor some advice. -

Everyone moves to Paul’s Churchyard. The five islands seen earlier on the river are now set up in the Churchyard, but now they carry the Five Senses. A ship carrying Moorish royalty is

sailing

on dry land towards the party. -

The Pageant moves into Cheapside with the islands in the lead. Once at the Little Conduit they encounter

London’s Triumphant Mount,

veiled in Error’s mist and guarded by his evil monsters. Truth drives the fog away to reveal London accompanied by Religion, Liberality, and Perfect Love. -

The whole

Triumph

moves to the cross in Cheap. Error continuously shroudsLondon’s Triumphant Mount

in his mist, and Truth keeps banishing it. This battle continues all the way to the Standard. -

At the Standard, Error succeeds in covering the Mount in mist until the Pageant reaches St. Laurence Lane End, where Truth drives the mist away.

-

The Pageant makes its way back to Guildhall for the feast.

-

Following the pink line on the map, the Lord Mayor, after feasting, is taken to St. Paul’s to

perform those yearly ceremonial rights which ancient and grave order hath determined,

with Error and Truth shrouding and uncovering the Mount along the way. -

Following the orange line on the map, the Pageant moves from St. Paul’s to

the entrance of his lordship’s gate near Leadenhall,

where Error is vanquished once and for all in a spectacular fireworks show.

Staging

While much is known about the mechanics of the court masque, the

mechanics of the Lord Mayor’s Show is an under-investigated field. In

The Triumphs of Truth, Thomas Middleton

worked with master Humphrey

Nichols, who made

the fire-workethat defeated Error, but what exactly is meant by

the fireworkis unknown. The direction in the text for Error’s fiery defeat states that

a Flame shootes from the head of Zeale, which fastening upon the / chariot of Error sets it on fire, and all the beasts that are joynde to it.Robert Withington says that Error and his companions were

obviously not alive(Withington 35), suggesting that effigies had replaced them in the chariot. This theory is sound because Error does not speak in the last scene of the Pageant, and an effigy could easily be substituted for the character of Error while everyone was distracted by the speeches of London and Truth. But how did Zeal shoot a flame from his head? Zeal could not have been an effigy, because he makes a speech as he shoots Error, saying

Then here’s to the destruction of the seate, / There’s nothing seene of thee but fire shall eate.With the danger involved, it seems unlikely that fireworks would have been rigged to an actor’s head. Perhaps Zeal shot some sort of symbolic flame towards Error’s chariot, and someone would have been standing by to start the fireworks and light the chariot on fire.

Somewhat easier to explain is the staging of the five islands that first

appear in the river Thames. These pieces of

the set,presumably constructed by John Grinkin, are established as islands when they are seen surrounded by the water of the Thames. Later, in Paul’s Churchyard, they appear on dry land. George Unwin explains their amphibiousness with the use of

trolleys(Unwin 279). By using trolleys, one could build a boat on which an

islandcould be constructed, then, as the Lord Mayor makes his way to and from Westminster, the islands could be loaded onto carts and hauled up to St. Paul’s.

The last problem with staging The Triumphs of

Truth is that of Error’s mist. It is described as

thick, sulphurous darkness,and as

a fog or mist.In reality, the

mistwas just material that Error used to shroud

London’s Triumphant Mountover and over again. The reason Truth and Error raise and lower the shroud all the way from the cross in Cheap to the end of the pageant is so that all the onlookers get to see what is going on. This action basically sums up the entire plot of the play -- Truth wins over Error -- so it is important that the audience sees it. Had the shroud been raised only once, the majority of Londoners watching the Show would have missed its message.

About Mayoral Pageantry

Civic pageantry does not refer to court masques or plays produced in

commercial theatres. Civic pageantry refers to entertainments that

were generally accessible to the public(Bergeron Civic 2). Examples of civic pageantry include the Royal Entry and the Lord Mayor’s Show. David M. Bergeron also points out that

[t]he involvement of the trade guilds and the cities in preparation and production of many of these entertainments also accounts for the ‘civic’ nature of the shows(3). The civic pageant, like the court masque,

was designed for a specific occasionand therefore had a limited lifespan. When the occasion ended,

so did the dramatic life of the pageant(3).

The Lord Mayor’s Show, celebrated on

the morrow next after Simon and Judes day,was probably the most familiar form of civic pageantry to a Londoner of the sixteenth or seventeenth century. The Show has its origins in another civic pageant called

The Midsummer Watch,which was what Robert J. Blackham calls

a sort of civic torchlight tattoo(Blackham 41). The Watch, which was

part folk tradition, part military exercise, part civic display,consisted of a

night-time procession through the City streetsof

armed men, bowmen, cresset light bearers, [. . .] musicians, and morris dancers(Lancashire 81). As with its successor, the Lord Mayor’s Show, the livery companies or trade guilds were involved in The Midsummer Watch. Each company was responsible for paying its cresset-bearers, archers, and men in harness, and the Company

to whom the mayor and sheriffs belonged provided their pageants, giants, and morris dancers(Unwin 269). The expense of The Watch to the Companies was significantly less than the expense of a Lord Mayor’s Show. Compare the £3 that the Carpenters spent in 1548 (269), to the £900 The Grocers spent on The Triumphs of Truth in 1613 (278).

The Midsummer Watch was suppressed by royal edict in 1539 (Manley 264), probably because of its

traditional Catholic dates and elements(Lancashire 83). Instead the

typical Watch pageantrytranslated into the secular Lord Mayor’s Show (83), and it became the

one great civic pageant of the year(Unwin 274), almost immediately after the suppression of The Watch (Manley 265).

Though the office of Lord Mayor has existed since 1189, the title of

Lord Mayor was not adopted until 1540(The Lord Mayor’s Show 2002), and Robert Withington suggests that the

first definite Lord Mayor’s Showwas not until 1553 (Withington 13), though some sort of procession had been going on since much earlier. In 1215, King John granted a charter that allowed the citizens of the City of London to elect their own Mayor, on the condition that the Mayor

be presented to the Sovereign for approval and [. . .] swear fealty to the Crown(The Lord Mayor’s Show 2002), and so the tradition of the procession to Westminster began. In fact, the original

Showconsisted of just the Mayor’s trip to Westminster (The Lord Mayor’s Show 2002). It was not until the Elizabethan era that the Lord Mayor’s Show became extravagant (Unwin 275).

Before the mid-fifteenth century,

the journey [to Westminster] was normally made entirely by land(Lancashire 82). It was not until 1453 that, according to popular legend, John Norman was the first Lord Mayor to make the trip to Westminster by water (Unwin 275). Robert Withington, however, disagrees, pointing out that Walderne, the Mayor of 1422, seems to have been the first to go by water (Withington 4). Perhaps John Norman is credited with making the first water journey because he was also the first to have

the barge that he sat inmaking him theburn on the water,,

originator of the fire-barge, which afterwards became a regular feature of all pageants(Unwin 275). Eventually, all the Companies bought or hired barges for the procession on the Thames (Blackham 45), which progressed in the

traditional hierarchyof the guilds (Knowles 166). Even if a Company was not a Great Company, its barge was still a

matter of guild pride(166).

The Lord Mayor’s Shows were

[c]ommissioned and paid for by the bachelors of the company(Manley 261), who were elected because they were the wealthiest men of the yeomanry, which was the general body of freemen of a livery company. The Lord Mayor’s Show was

the Company’s gift to one of its illustrious members(261). As time went on, the

giftscost more each year.

The Companies showed their wealth and affluence through the extravagance

of their pageant. This resulted in a

healthy rivalry,which also

generate[d] expensive productions(Bergeron Civic 138). For example, the 1561 pageant costs £151, while the 1602 pageant cost an excess of £747 (138), and The Triumphs of Truth in 1613 cost around £900 (Unwin 278). Along with rising costs came the growing intricacy of the show itself. At first, the pageants consisted of a silent show, but by the Elizabethan era

the characters were given long speeches(Blackham 43). Eventually, the pageants had about a

half-dozen different scenesand

numerous personages,all of which George Unwin calls

natural product[s] of the Elizabethan age(Unwin 275).

The first pageant

textthat we know of was written by George Peele in 1585 for Sir Wolstone Dixie, Skinner. The text is a pamphlet which contains

only the speeches spoken by the characters in the pageant(Withington 23), unlike Middleton’s text of The Triumphs of Truth (1613), which includes descriptions and explanations of the emblematic costumes. Peele’s 1585 text is also significant because it is the first time a

well-known dramatist [was] responsible for the entertainment(Bergeron Civic 131). Other widely known writers who penned civic pageants were George Gascoigne, John Lyly, Ben Jonson, Thomas Dekker, John Webster, Thomas Heywood, and Anthony Munday (4).

The pageant theatre,says David M. Bergeron,

is the quintessence of emblematic theatre(Bergeron Civic 2), and the writer who was used to creating pieces for the theatre would have to take a different approach when writing civic pageantry. The pageant had to be accessible and understandable to those people watching, and therefore could not be plot-based, and if there is

little or no plot, then the dramatic burden of the pageant must fall on theme(7). The theme of The Triumphs of Truth is

Truth conquers Error.Anyone watching the pageant at any point on the route would be able to discern this theme from the emblematic costumes and the simple action, even without being able to hear the speeches.

The Elizabethan and Jacobean eras were

sympathetic to and indeed educated to symbolism(Bergeron Civic 2), and therefore playwrights and pageantwrights could use symbols and emblems to tell the crowd what exactly the pageant was about. At the same time, the symbols were used to reinforce the greatness of the host Company (like the five islands in The Triumphs of Truth

garnishedwith fruit trees, drugs, and spiceries, which are meant to glorify the Grocers’ Company), and to promote the

oligarchic dominationof the Companies (Manley 267). The Lord Mayor’s Show

celebrat[ed] the power and the values of the City’s innermost mercantile elite(284). As much as it was a day of fun for the average Londoner, the Show was also used as propaganda for the Companies.

The reign of James I

was the Golden Age of the Lord Mayor’s Show(Unwin 277). As the seventeenth century progressed,the pageants reached the height of their extravagance (Blackham 43), only to move in a new direction during the Restoration. The Shows of the Restoration were comical, and replaced the

stilted speechesof the Renaissance with

jocular songs and clowning(43-44). Raymond D. Tumbleson says the shift from serious to silly is because

[b]y 1701, there was no longer a need to enact symbolic Triumphs of London because London had triumphed(Tumbleson 54).

About the Livery Companies

The livery companies were the most important organizations in London in

the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and even more important to

London, perhaps, than the monarchy. The livery companies were

responsible in part for the extreme wealth in London, and even provided

the monarch with money. Robert J. Blackham writes,

The livery companies, with their political and municipal power, are peculiar to London. No other city has permitted such a development of its mistries and trades, nowhere else in England have chartered associations of the kind attained such wealth and power(Blackham 2).

The livery companies originated from medieval organizations called

guilds, which were

voluntary associations formed originally for mutual protection, with religious, benevolent and social elements(Grocers’ 1). The guilds were a

mixture of worldly and religious idealsand there was a strong sense of

Christian brotherhoodbetween the members of a particular guild (Blackham 2). Being a member of a Worshipful Company was a source of pride and dignity for

the old world trader(3).

The guilds were not just for

social elementsand

mutual protection,they were also about money. The guildsmen were not just

merchants, traders and craftsmen,they were also

bankers and financiers(13) helping to establish London as the commercial and financial capital of the world. Sir Thomas Gresham, a Mercer, was responsible for the building of the Royal Exchange, which helped develop overseas trade, and helped London expropriate the title of

commercial capitalfrom Antwerp (13).

Regarding the commercial aspect of the guilds, Blackham says they were

designed to represent the interests of [. . .] the employer, the workman and the consumer," though those interests may be "distinct and antagonistic(12). The guilds protected its members by being able to regulate

the establishment of businesses in the crafts and trades they controlled(Rappaport 29). No one could practice a certain trade except the members of the corresponding Company (Blackham 13), and this protected the employer from the

incompetency of the artisan(11). The Company controlled the intake of apprentices and the rates of wages, and no journeyman was permitted to work outside his Company (13). The Company was committed to protecting the journeyman, who was a

trained workman,by

preventing his being undersold in the labour market by an unlimited number of competitors(11).

It is no surprise, with their great financial and political power, that

the livery companies were the

most important social organizations in sixteenth-century London(Rappaport 26). By the early seventeenth century, two-thirds of the men in London were citizens of a livery company (53), and the responsibilities of the companies had been extended to providing relief for the poor, collecting taxes, and organizing pageants (26).

The first twelve companies eventually came to be known as

The Twelve Great Companies.They are: the Mercers, the Grocers (for whom Thomas Middleton wrote The Triumphs of Truth), the Drapers, the Fishmongers, the Goldsmiths, the Merchant Taylors, the Skinners, the Haberdashers, the Salters, the Ironmongers, the Vintners and the Clothworkers. These Companies wielded the true power in the City of London. Each year the Lord Mayor was selected from one of the twelve, and that Company was responsible for organizing and funding that year’s Lord Mayor’s Show.

In fact, citizens, or freemen, were the only people who held any power

in London. To become a freeman, a man who had just finished his

apprenticeship would swear an oath before his master and the governors

of the Company associated with his trade in

a simple ceremony at the hall,and become a member of the Company (Rappaport 23-4). Soon after, the former apprentice (usually now a journeyman), would go to Guildhall where he would be sworn as a citizen or a freeman of London (24).

With his new found freedom, the citizen acquired a number of rights

that the

non-freecould not enjoy. These rights included the right to vote and the right to hold municipal office (30), and the right to

engage independently in economic activity(29). It is interesting to note that, while there was no law preventing women from accepting the freedom,

it is clear they were excluded from the right and privileges of citizens(49). In practice, they were excluded from becoming apprentices, with a few exceptions. There were only seventy-three women enrolled as apprentices during the entire sixteenth century (37), and in fact, the Weavers’ Company made it policy in 1550

not to take on women apprentices(37).

Apprentices were the bottom of the social hierarchy within the livery

companies (232). Above them

were the journeymen, the householders, the liverymen, and the assistants

at the very top (217). The

apprentices could work their way up through the ranks, but first they

had to complete their apprenticeship. Apprenticed to a master for a

certain number of years, the apprentice had a set of rules he was

expected to follow. He was not allowed to marry or

commit fornication,nor take part in any

unlawful gameslike dice or cards, and he was not supposed to go to the taverns or the theatres (234). The master provided his apprentice with clothing, as well as room and board (234). When the apprentice completed his term, the master also

paid the fees for making him a free man and a member of the company(235).

Above the apprentices in the hierarchy were the journeymen, who worked

for wages, and householders, who ran their own shops (221). These two groups formed a

sub-organization in the Company called the yeomanry. The origins of

the yeomanry lie with

illegal fraternities of journeymen in late medieval London(219). These journeymen capitalized on labour shortages, working only for double or triple the normal wage (219), and threatening

strikes against masters who employed foreigners(220). It was like a union for journeymen. Something happened during the fifteenth century, in which the fraternities

underwent a striking transformation(220), and by the sixteenth century London’s yeomanries included journeymen and householders -- the

employees and employers(220).

The yeomanry of the Renaissance was a

somewhat autonomous organizationwithin a Company (219), and included the men who were

not eliteenough to be in

the livery,which was the other sub-organization within the Company. The livery included only one-fifth of all members, making the yeomanry the bulk of the company (219). The yeomanry was able to stay

somewhat autonomousby providing its own income through the collection of

quarterage dues(Archer 108). Among the responsibilities of the yeomanry was

enforcing many of the regulations governing a company’s craft or trade(Rappaport 224).

In the Great Companies, there was a

separate livery of the yeomanry called ‘the bachelors’(226). This special livery would be created only on the year when a member of that company was going to serve as Lord Mayor (226). The bachelors were responsible for

attend[ing] upon the Lord Mayor at his going to Westminster to take his oath and certain other days of like service(226). On the day of the Lord Mayor’s Show, the bachelors would also be required to dress in special costume (226). Being elected to bachelor status

marked an important distinction between the men of substance who might eventually attain the livery of their company and the lesser artisans and shopkeeps who never would(Manley 262-63).

Movement was possible between the members of the yeomanry and the elite

livery. One could be promoted from the yeomanry to the livery (Rappaport 221), but

only the wealthiest householders were chosen(256). It was expensive to stay in the livery. Upon being chosen, one would have to pay an admission fee (257), and buy a

fur-lined cloak and satin hoodfor formal occasions (218). If a liveryman’s funds were dwindling, he could find himself back in the yeomanry (258).

The responsibilities of a liveryman included serving on committees which

performed important administrative, [and] deliberative [. . .] functions,as well as

overseeing lawsuits and appeals for action to the crown or parliament(255). The elite liverymen, the assistants, were required to attend court, and serve periodically as warden or master (268).

Since the Companies were so wealthy, the Tudor monarchy was

heavily dependent on the good will of the Citybecause

the City’s wealth was a source of financing more dependable than Parliament(Manley 219). When a monarch demanded money from a Company, it would collect from its members to meet the sum of the request. When Queen Mary demanded a loan from the City in 1558, the Grocers Company had to come up with £7 555. These compulsory loans were called Benevolences (Grocers’ 10). Queen Elizabeth frequently demanded money, which she would borrow

free of interest, and then was graciously pleased to lend at 8 per cent!(10). The Stuart family, however, was the worst for borrowing huge sums of money and seldom repaying it. To fund James I, the Companies

supplied the money first from their common stock, then by assessment, at first voluntary, subsequently compulsory of individual members(10).

Despite being constantly squeezed for money, the Companies were still

able to partake in good works, such as establishing almshouses and

providing pensions (Archer

120). The Companies would also

assistwidows of Company men, and help the younger members of the Company by providing

two- to four-years interest-free loans of ten to fifty pounds to young men in need of capital to begin businesses(Rappaport 39).

The livery companies have been described as

the rock upon which the life of the City was built(Grocers’ 1), and their presence certainly helped London achieve great status during the Renaissance.

About the Grocers’ Company

The Grocers’ Company, one of the Twelve Great Companies, emerged from a

much older Company -- the Pepperers. The Pepperers were first mentioned

in 1180 as the Gilda

Piperariorum (Grocers’ 1).

Unlike many other guilds, the Pepperers did not specialize in one

particular area, but rather in many areas. They were

recognised as general traders who bought and sold [. . .] all kinds of merchandise(2). They were also the guild that was in charge of weighing merchandise in the City (2), and they had access to warehouses and shops for the purpose of

garbling or cleaning spices, drugs and kindred commodities(2). Garbling meant to check for fraud by

cleansinggood that were sold by weight, like spices and drugs (6).

The first mention of the Grocers is in 1373, when they were referred to as the

Company of

Grossers(6). It was not until 1376, after revising their ordinances, that they came to be known as

the Grocers of London (Les Grocers de Loundres)(6).

As was customary, the Grocers had a patron saint -- Saint Antony of Coma who was

credited with the power of curing skin diseases(5). The reason for adopting Antony of Coma as their patron saint had little to do with curative powers and more to do with location. The Pepperers occupied Soper’s Lane and attended the church at the south end of the lane, the Church of St. Antolin (another form of Antony) (5), and because of their membership in the church, St. Antony of Coma seemed a natural choice for a patron saint.

The Grocers Company was very wealthy during the reign of James I. When one of their

members, Sir Thomas

Middleton (not to be confused with Thomas Middleton the writer) was chosen to

be the Lord Mayor in 1613,

the Grocers were prepared to spend almost £900 on their pageant, The Triumphs of Truth (Unwin 278). The

costs included: £200 for drapery, including blue gown sleeves for 124

aldermen; £48 for 288 white staves for the whifflers (men employed to

keep the way clear for a procession), and for 780 torches; £67 for

mercery; and £282 for the poetry, scene painting, and general

upholstery. On top of these costs, the Grocers paid the wages of the

city waits, 32 trumpeters, and 18 flourishers of long swords. The cost

of the loot to be tossed into the crowd was also enormous as the Grocers

provided 500 loaves of sugar, 36 lbs. of nutmegs, 24 lbs. of dates, and

114 lbs. of ginger (278).

As a salute to the Grocers’ Company, Thomas Middleton, author of The Triumphs of

Truth, followed the tradition of including islands

garnishedwith fruit trees, drugs, and spiceries. The tropical island was a

permanent feature of the Lord Mayor’s Shows in the seventeenth century(271), as it served to indicate the Grocers’

association with the East from which they imported their drugs and spices(Blackham 41).

The Grocers were fond of Middleton’s work, and they hired him again in 1617, and several times more

until his death in 1627.

About the Author

Thomas Middleton was born to

William and Anne Middleton in London in

1580 (Heinemann 49). His father was a prosperous

brickmason and landlord,according to David M. Holmes (xvi), or a

bricklayer and builder,according to Margot Heinemann (49). William died in 1586, when Middleton and his sister Avice were just young (49).

His mother remarried a

broken grocernamed Thomas Harvey. Harvey spent the Middletons’ money recklessly, which resulted in a series of lawsuits against him (49).

At the age of eighteen, Middleton matriculated at Queen’s College Oxford (Holmes xvii), but he never

finished his degree (Heinemann

49). In 1601, he

decided to

accompany the playersin hopes of making some money (50), and ended up marrying Mary Marbecke (50), the sister of one of the Admiral’s Men. They had a son called Edward (Holmes xvii).

Critical opinion of Middleton

varies. His works have been described in many different ways. His

comedies have been called

cynical,

amoral,

disgusting,

boring,and

profoundly serious moral fables,and his tragedies, according to T.S. Eliot, have

no point of view(qtd. in Heinemann 1). Some sense a

strong Calvinist biasin his work (1), while others feel his work suggests that

he came from a moderate Puritan background(51).

During his early years as a dramatist, Middleton wrote primarily for the boy

players,

particularly for the Children of St. Paul’sfor whom

he did six plays(63). Middleton also wrote for the Children of the Revels, Lady Elizabeth’s, and Prince Charles’s companies, and, from 1615 onward, the King’s Men (Holmes xviii). His play A Game at Chess (1624), a

sharp satire on royal policy,was the

greatest box-office success of the whole Jacobean period(Heinemann 2). With such success came fame, or, in Middleton’s case, infamy. The King heard of the satirical A Game at Chess and

ordered it to be suppressed and the dramatist punished(130). As a result of this decree, Middleton was forced into hiding in 1624 (130).

Middleton’s first experience

with writing civic pageants was in 1603, when he contributed a speech for Zeal in Dekker’s entertainment for the

Royal Entry of James I into London (124). He proceeded to write his own pageant in 1613 entitled The Triumphs of Truth. Critics assert that this pageant was

his best work for the civic stage. It was his

finest and his most elaboratepageant, as well as the

most expensive mayoral pageant of the Renaissance(Bergeron Civic 179).

It is interesting to note that Middleton sneers at fellow dramatist, Anthony Munday, in the very beginning of the

text, and later acknowledges him for providing

apparrell and porters.Middleton takes the opportunity to

hurl a few barbs at his rivalin The Triumphs of Love and Antiquity, written for the Skinners in 1619 (Bergeron Civic 189), but then collaborates with Munday in 1621 (191), and again in 1623 (195). Perhaps their rivalry was just for show, or maybe they were forced to collaborate because they needed the work and the money.

The Grocers’ Company hired Middleton once again to write the Lord Mayor’s Show of 1617. The Triumphs of Honour and Industry (for the record, six of the

seven shows written by Middleton were entitled The Triumphs of...), was more

conservative and traditional than The Triumphs of Truth, and

the result is a rather undistinguished work(186). Distinguished or not, Middleton was paid handsomely for his efforts.

Middleton wrote seven Lord

Mayor’s Pageants in all: The Triumphs of Truth (1613), The Triumphs of Honour and Industry (1617), The

Triumphs of Love and Antiquity (1619), The Sun in

Aries (1621),

The Triumphs of Honour and Virtue (1622), The

Triumphs of Integrity (1623), and The Triumphs of Health and

Propsperity (1626) (Tumbleson 57).

He was also the author or co-author of

some twenty plays,as well as several court masques (Heinemann vii). In addition to his creative work, Middleton was appointed City Chronologer in 1620, a position he held until his death in 1627 (Holmes xviii).

References

-

Citation

Archer, Ian W. The Pursuit of Stability: Social Relations in Elizabethan London. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1991.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Bergeron, David M. English Civic Pageantry 1558–1642. London: Edward Arnold, 1971.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Blackham, Colonel Robert J. The Soul of the City: London’s Livery Companies. Their Storied Past, Their Living Present. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co., 1932.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Grocers’ Company. A Short History of the Grocers’ Company, Together With a Description of the Grocers’ Hall and the Principal Objects Therein. London: Metcalfe and Cooper, 1960.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Heinemann, Margot. Puritanism and Theatre: Thomas Middleton and Opposition Drama under the Early Stuarts. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1980.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Holmes, David M. The Art of Thomas Middleton. Oxford: Clarendon, 1970.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Knowles, James.The Spectacle of the Realm: Civic Consciousness, Rhetoric and Ritual in Early Modern London.

Theatre and Government Under the Early Stuarts. Ed. J.R. Mulyne and Margaret Shewring. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1993. 157–89.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Lancashire, Anne K.Continuing Civic Ceremonies of 1530s London.

Civic Ritual and Drama. Ed. Alexandra F. Johnston and Wim Hüsken. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1997.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Lord Mayor’s Show. London Stock Exchange Group. open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Manley, Lawrence. Literature and Culture in Early Modern London. Cambridge: Cambridge, UP, 1997.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Middleton, Thomas. The Triumphs of Truth. London, 1613. STC 17904. Reprint. EEBO. Web. [Differs from STC 17903 in that it contains an additional entertainment celebrating Hugh Middleton’s New River project, known as the Entertainment at Amwell Head.]This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Middleton, Thomas. The Triumphs of Truth. London, 1613. STC 17903. Reprint. EEBO. Web.[Differs from STC 17904 in that it does not contain the additional entertainment.]This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Rappaport, Steve. Worlds Within Worlds: Structures of Life in Sixteenth-Century London. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1989.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Tumbleson, Raymond D.The Triumph of London: Lord Mayor’s Day Pageants and the Rise of the City.

The Witness of Times: Manifestations of Ideology in Seventeenth Century England. Ed. Katherine Z. Keller and Gerald J. Schiffhorst. Pittsburgh: Duquesne UP, 1993. 53–68.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Unwin, George. The Gilds and Companies of London. 4th ed. London: Frank Cass, 1963.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Withington, Robert. English Pageantry: An Historical Outline. Vol. 2. 1926. Reprint. New York: Benjamin Blom, 1963.This item is cited in the following documents:

Cite this page

MLA citation

Critical Companion to The Triumphs of Truth.The Map of Early Modern London, edited by , U of Victoria, 20 Jun. 2018, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/TRIU1_critical.htm.

Chicago citation

Critical Companion to The Triumphs of Truth.The Map of Early Modern London. Ed. . Victoria: University of Victoria. Accessed June 20, 2018. http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/TRIU1_critical.htm.

APA citation

2018. Critical Companion to The Triumphs of Truth. In (Ed), The Map of Early Modern London. Victoria: University of Victoria. Retrieved from http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/TRIU1_critical.htm.

RIS file (for RefMan, EndNote etc.)

Provider: University of Victoria Database: The Map of Early Modern London Content: text/plain; charset="utf-8" TY - ELEC ED - Jenstad, Janelle T1 - Critical Companion to The Triumphs of Truth T2 - The Map of Early Modern London PY - 2018 DA - 2018/06/20 CY - Victoria PB - University of Victoria LA - English UR - http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/TRIU1_critical.htm UR - http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/xml/standalone/TRIU1_critical.xml ER -

RefWorks

RT Web Page SR Electronic(1) A6 Jenstad, Janelle T1 Critical Companion to The Triumphs of Truth T2 The Map of Early Modern London WP 2018 FD 2018/06/20 RD 2018/06/20 PP Victoria PB University of Victoria LA English OL English LK http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/TRIU1_critical.htm

TEI citation

<bibl type="mla"> <title level="a">Critical Companion to The Triumphs of Truth</title>. <title level="m">The Map of Early Modern London</title>, edited by <editor><name ref="#JENS1"><forename>Janelle</forename> <surname>Jenstad</surname></name></editor>, <publisher>U of Victoria</publisher>, <date when="2018-06-20">20 Jun. 2018</date>, <ref target="http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/TRIU1_critical.htm">mapoflondon.uvic.ca/TRIU1_critical.htm</ref>.</bibl>Personography

-

James Campbell

JDC

English 412, Representations of London, Fall 2002; research assistant, 2002–03; BA honours student, English Language and Literature, University of Windsor.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Textual Introduction

-

First Transcriber

Contributions by this author

James Campbell is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

James Campbell is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Janelle Jenstad

JJ

Janelle Jenstad, associate professor in the department of English at the University of Victoria, is the general editor and coordinator of The Map of Early Modern London. She is also the assistant coordinating editor of Internet Shakespeare Editions. She has taught at Queen’s University, the Summer Academy at the Stratford Festival, the University of Windsor, and the University of Victoria. Her articles have appeared in the Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Early Modern Literary Studies, Elizabethan Theatre, Shakespeare Bulletin: A Journal of Performance Criticism, and The Silver Society Journal. Her book chapters have appeared (or will appear) in Performing Maternity in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2007), Approaches to Teaching Othello (Modern Language Association, 2005), Shakespeare, Language and the Stage, The Fifth Wall: Approaches to Shakespeare from Criticism, Performance and Theatre Studies (Arden/Thomson Learning, 2005), Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society (Brill, 2004), New Directions in the Geohumanities: Art, Text, and History at the Edge of Place (Routledge, 2011), and Teaching Early Modern English Literature from the Archives (MLA, forthcoming). She is currently working on an edition of The Merchant of Venice for ISE and Broadview P. She lectures regularly on London studies, digital humanities, and on Shakespeare in performance.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Stub

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

Author of Textual Introduction

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Course Instructor

-

Course Supervisor

-

Course supervisor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Structure and Toponyms)

-

Final Markup Editor

-

GIS Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Modern)

-

Geographical Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Main Transcriber

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Name Encoder

-

Peer Reviewer

-

Primary Author

-

Project Director

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Reviser

-

Second Author

-

Second Encoder

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Janelle Jenstad is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Janelle Jenstad is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Tye Landels-Gruenewald

TLG

Research assistant, 2013-15, and data manager, 2015 to present. Tye completed his undergraduate honours degree in English at the University of Victoria in 2015.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

MoEML Researcher

-

Name Encoder

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

Contributions by this author

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Lacey Marshall

LM

English 412, Representations of London, Fall 2002; BA combined honours student, English language and literature and German, University of Windsor. Lacey went on to study speech-language pathology at Dalhousie University.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Critical Introduction and Essays

-

Author of Introduction

-

Toponymist

Contributions by this author

Lacey Marshall is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kim McLean-Fiander

KMF

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach, 2015–present; Associate Project Director, 2015–present; Assistant Project Director, 2013-2014; MoEML Research Fellow, 2013. Kim McLean-Fiander comes to The Map of Early Modern London from the Cultures of Knowledge digital humanities project at the University of Oxford, where she was the editor of Early Modern Letters Online, an open-access union catalogue and editorial interface for correspondence from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. She is currently Co-Director of a sister project to EMLO called Women’s Early Modern Letters Online (WEMLO). In the past, she held an internship with the curator of manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library, completed a doctorate at Oxford on paratext and early modern women writers, and worked a number of years for the Bodleian Libraries and as a freelance editor. She has a passion for rare books and manuscripts as social and material artifacts, and is interested in the development of digital resources that will improve access to these materials while ensuring their ongoing preservation and conservation. An avid traveler, Kim has always loved both London and maps, and so is particularly delighted to be able to bring her early modern scholarly expertise to bear on the MoEML project.Roles played in the project

-

Associate Project Director

-

Author

-

Author of MoEML Introduction

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Contributor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Contributor

-

Data Manager

-

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (People)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Managing Editor

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Research Fellow

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Second Author

-

Secondary Author

-

Secondary Editor

-

Toponymist

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Kim McLean-Fiander is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Kim McLean-Fiander is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Joey Takeda

JT

Programmer, 2018-present; Junior Programmer, 2015 to 2017; Research Assistant, 2014 to 2017. Joey Takeda is an MA student at the University of British Columbia in the Department of English (Science and Technology research stream). He completed his BA honours in English (with a minor in Women’s Studies) at the University of Victoria in 2016. His primary research interests include diasporic and indigenous Canadian and American literature, critical theory, cultural studies, and the digital humanities.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Stub

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Date Encoder

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Bibliography)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Agas)

-

Junior Programmer

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Encoder

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Second Author

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Editor

Contributions by this author

Joey Takeda is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Joey Takeda is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Stewart Arneil

Programmer at the University of Victoria Humanities Computing and Media Centre (HCMC) who maintained the Map of London project between 2006 and 2011. Stewart was a co-applicant on the SSHRC Insight Grant for 2012–16.Roles played in the project

-

Programmer

Stewart Arneil is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Stewart Arneil is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Martin D. Holmes

MDH

Programmer at the University of Victoria Humanities Computing and Media Centre (HCMC). Martin ported the MOL project from its original PHP incarnation to a pure eXist database implementation in the fall of 2011. Since then, he has been lead programmer on the project and has also been responsible for maintaining the project schemas. He was a co-applicant on MoEML’s 2012 SSHRC Insight Grant.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of abstract

-

Conceptor

-

Encoder

-

Name Encoder

-

Post-conversion and Markup Editor

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

Contributions by this author

Martin D. Holmes is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Martin D. Holmes is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

St. Anthony of Egypt

Saint Antony of Egypt

(b. 251, d. 356)Patron saint of the Grocer’s Company. Known for withstanding temptation, founding Christian monasticism, and healing skin diseases.St. Anthony of Egypt is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thomas Dekker is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Sir Wolstan Dixie is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth Tudor I Queen of England and Ireland

(b. 7 September 1533, d. 24 March 1603)Queen of England and Ireland.Elizabeth I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

George Gascoigne is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Sir Thomas Gresham is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Grinkin

Presumed set designer of Triumphs of Truth.John Grinkin is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thomas Harvey

(b. 1559, d. 1606)Second husband of Anne Middleton and stepfather of Thomas Middleton.Thomas Harvey is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thomas Heywood is mentioned in the following documents:

-

James VI and I

King James Stuart VI and I

(b. 1566, d. 1625)King of Scotland, England, and Ireland.James VI and I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Ben Jonson is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Lyly is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Mary Marbecke

Wife of Thomas Middleton.Mary Marbecke is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Mary I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thomas Middleton is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Sir Thomas Middleton is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Anne Middleton is mentioned in the following documents:

-

William Middleton is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Avice Middleton

Sister of Thomas Middleton and wife of Allen Waterer.Avice Middleton is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Edward Middleton

Son of Thomas Middleton and Mary Marbecke.Edward Middleton is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Anthony Munday

(bap. 1560, d. 1633)Playwright, actor, pageant poet, translator, and writer. Possible member of the Draper’s Company and/or the Merchant Taylor’s Company.Anthony Munday is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Humphrey Nichols is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Norman

John Norman Sheriff Mayor

(fl. 1461-68)Sheriff of London from 1443—1444 CE. Mayor from 1453—1454 CE. Member of the Drapers’ Company. Not to be confused with John Norman.John Norman is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Nicholas Okes is mentioned in the following documents:

-

George Peele is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Sir William Walderne

William Walderne Sheriff Mayor

Sheriff of London from 1399—1400 CE. Mayor from 1412—1413 CE and from 1422—1423 CE. Member of the Mercers’ Company.Sir William Walderne is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Webster is mentioned in the following documents:

Locations

-

Guildhall is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Soper Lane

Soper Lane was located in the Cordwainers Street Ward just west of Walbrook and south of Cheapside. Soper Lane was home to many of the soap makers and shoemakers of the city (Stow 1:251). Soper Lane was on the processional route for the lord mayor’s shows.Soper Lane is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Westminster Palace is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Baynard’s Castle

Located on the banks of the Thames, Baynard’s Castle was built sometime in the late eleventh centuryby Baynard, a Norman who came over with William the Conqueror

(Weinreb and Hibbert 129). The castle passed to Baynard’s heirs until one William Baynard,who by forfeyture for fellonie, lost his Baronie of little Dunmow

(Stow 1:61). From the time it was built, Baynard’s Castle wasthe headquarters of London’s army until the reign of Edward I (1271-1307) when it was handed over to the Dominican Friars, the Blackfriars whose name is still commemorated along that part of the waterfront

(Hibbert 10).Baynard’s Castle is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Paul’s Chain

Paul’s Chain was a street that ran north-south between St Paul’s Churchyard and Paul’s Wharf, crossing over Carter Lane, Knightrider Street, and Thames Street. It was in Castle Baynard Ward. On the Agas map, it is labelledPaules chayne.

The precinct wall around St Paul’s Church had six gates, one of which was on the south side by Paul’s Chain. It was here that a chain used to be drawn across the carriage-way entrance in order to preserve silence during church services.Paul’s Chain is mentioned in the following documents:

-

St. Paul’s Churchyard is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Cheapside Street

Cheapside, one of the most important streets in early modern London, ran east-west between the Great Conduit at the foot of Old Jewry to the Little Conduit by St. Paul’s churchyard. The terminus of all the northbound streets from the river, the broad expanse of Cheapside separated the northern wards from the southern wards. It was lined with buildings three, four, and even five stories tall, whose shopfronts were open to the light and set out with attractive displays of luxury commodities (Weinreb and Hibbert 148). Cheapside was the centre of London’s wealth, with many mercers’ and goldsmiths’ shops located there. It was also the most sacred stretch of the processional route, being traced both by the linear east-west route of a royal entry and by the circular route of the annual mayoral procession.Cheapside Street is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Little Conduit (Cheapside)

The Little Conduit in Cheapside, also known as the Pissing Conduit, stood at the western end of Cheapside outside the north corner of Paul’s Churchyard. On the Agas map, one can see two water cans on the ground just to the right of the conduit.Little Conduit (Cheapside) is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Cheap Ward

MoEML is aware that the ward boundaries are inaccurate for a number of wards. We are working on redrawing the boundaries. This page offers a diplomatic transcription of the opening section of John Stow’s description of this ward from his Survey of London.Cheap Ward is mentioned in the following documents:

-

The Standard (Cheapside) is mentioned in the following documents:

-

St. Laurence Lane (Guildhall) is mentioned in the following documents:

-

St. Paul’s Cathedral

St. Paul’s Cathedral was—and remains—an important church in London. In 962, while London was occupied by the Danes, St. Paul’s monastery was burnt and raised anew. The church survived the Norman conquest of 1066, but in 1087 it was burnt again. An ambitious Bishop named Maurice took the opportunity to build a new St. Paul’s, even petitioning the king to offer a piece of land belonging to one of his castles (Times 115). The building Maurice initiated would become the cathedral of St. Paul’s which survived until the Great Fire of 1666.St. Paul’s Cathedral is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Leadenhall is mentioned in the following documents:

-

The Thames is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Royal Exchange is mentioned in the following documents:

-

St. Antholin is mentioned in the following documents:

-

St. Paul’s School is mentioned in the following documents:

Organizations

-

The Grocers’ Company

The Worshipful Company of Grocers

The Grocers’ Company (previously the Pepperers’ Company) was one of the twelve great companies of London. The Grocers were second in the order of precedence established in 1515. The Worshipful Company of Grocers is still active and maintains a website at http://www.grocershall.co.uk/, including a brief history.![The coat of arms of the Grocers’ Company, from Stow (1633). [Full size image]](graphics/Grocers_sm.jpg)

The coat of arms of the Grocers’ Company, from Stow (1633). [Full size image] This organization is mentioned in the following documents: