City Dog House

The City Dog House, located in northern London, was adjacent to Moorfields1 and was located outside of The Wall and the city wards.2 It was also referred to by the Lord Maiors dog-house, The Lord Mayors dogge-house, the Lord Mayors Dog-house, the Dog-house in Finsbury Field, and the Lord Mayor’s Dog-kennel. On the Agas map, it is labelled as

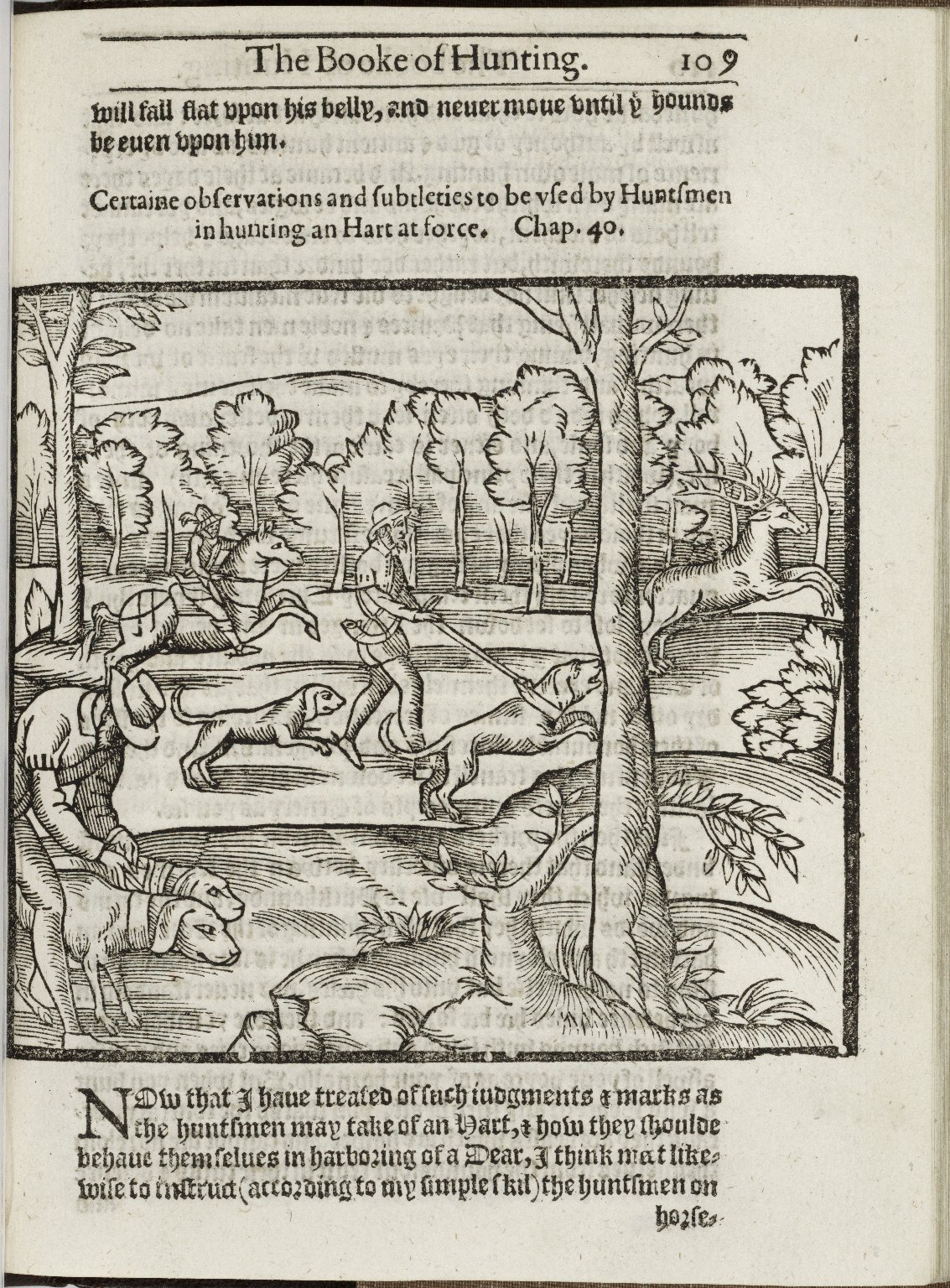

Dogge hous.Built in 1512, the Lord Mayor’s dog house, as it was most frequently called, housed the Lord Mayor’s hunting dogs (Hope 42). This area was popular for recreational pursuits, such as archery, as depicted on the Agas map.3 Before 1527, when Moorfields and Finsbury Field were drained, the place was also popular for ice skating (Thornbury 196). Besides having a history as a place for recreation, the Dog House was located near Finsbury Manor, which was owned by the Lord Mayor and located in the outskirts of London, where the frequently mentioned odour and noise of the Dog House would be less bothersome (Poore 336).

The hounds were looked after by an officer called the Common Hunt, who resided in or near the Dog House itself. The Common Hunt was a high-ranking position, second only to the Master Sword-bearer (Pennant 347). The Common Hunt, also called Master Common Hunt, attended to the Lord Mayor on Mondays, Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays (Pennant 348).

By the early 1600s, the Dog House seems to have fallen into disrepair, being referred to as

verie old and reuinous and not fit for habitationas well as having

stinking smelles(Waller 34). The Common Hunt writes next year

that it doth rayne into the rooms of the Dogge hous’e throughout, and that the same will, in short time,- fall downe(Waller 34). The house, however, remained standing, though we do not hear about it for some time so perhaps some repairs were finally made. After some debate on the importance of the Common Hunt’s position in preserving the history of London, the office was abolished in 1807.

The Lord Mayor allowed well-off citizens to use his hounds to hunt. These hounds were used for an

event called the citizen’s common hunt (not to be confused with the officer mentioned above). Strype describes one of these common hunts on September 18th, 1562:

There was a great cry for a mile, then the hounds killed him [the fox] at St. Giles; a great hallooing at his death and blowing of horns; and the Lord Mayor and all his company rode through London to his place in Lombard Street(Strype 25).

The hounds were treated well. After a stag hunt, they were given choice pieces of

meat from the dead stag, and on their return to the Dog House the hounds had their feet bathed and greased (Velten 89). The popularity of the common hunt fell until in the late eighteenth century, when the Lord Mayor’s hounds were only used once a year for the Epping Forest hunt. Previously a respectable

and serious affair, the Epping hunt had become a laughingstock by 1807 when the City of London abolished the office of the Common Hunt. Without the Lord Mayor’s hounds, fewer hounds, that were of poorer breeding, were used, along with horses

of lower quality. Riders were frequently drunk and the affair extremely chaotic. The

Epping hunts ended in 1847 (Velten 94).

The Dog House was certainly well known in its day, as evidenced by references to it in period literature.

In Thomas Dekker’s Belman of London, for example, a character refers to hounds from the City Dog House, saying,

nay my Lord Maiors Hounds at the dog-house being bidden to the funerall banquet of a dead horse, could not pick the bones cleaner(Dekker, Belman 23). It was also one of the few places where ordinary Londoners could witness hunting techniques like the practice of coupling younger and older dogs for training. Dekker describes a pair of people who

went away like a cupple of hounds from the dogge-house(Dekker, A Strange Horse-Race 24). Other literary references allow us to guess at conditions in the Dog House. For example, one Londoner claimed a prison

stinkes more then the Lord Mayors dogge-house(G.M. 13). Others mention the Lord Mayor’s Dog House as a fanciful place to commit suicide by dogs or as a place to throw someone you are not fond of. The noise and smell thus made it a proverbially frightful place for early modern Londoners (Jessey 130; Rowley 64). We can guess at the hounds’ diets from a mention in Natura Exenterata of the Dog House in Finsbury Field as being a place to acquire horse marrow, and also from Dekker’s above comment regarding the dead horse (Philiatros 216).

Notes

References

-

Citation

Dekker, Thomas. The Belman of London. London: 1608. STC 6482. Subscription.FS Early English Books Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Dekker, Thomas. A Strange Horse-race. London: 1613. STC 6528. Subscription. Early English Books Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

G.M.. Certaine Caracters and Essayes of Prison and Prisoners. London: 1618. EEBO. STC 18318. Subscription.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Hope, Valerie. My Lord Mayor: Eight Hundred Years of London’s Mayoralty. London: Weidenfield and Nicolson, 1989.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Jessey, Henry. The Exceeding Riches of Grace. London: 1647. EEBO. Wing J688. Subscription.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Pennant, Thomas. Some Account of London. London: 1813. Open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Philiatros. Natura Exenterata: or Nature Unbowelled. London: 1655. EEBO. Wing N241. Subscription.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Poore, G. V.London, Ancient and Modern, From a Sanitary Point of View.

Public Health. 1 (1889): 335-343. Open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Strype, John. A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate, and Government of those Cities. London, 1720. Reprint. as An Electronic Edition of John Strype’s A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster. Ed. Julia Merritt (Stuart London Project). Version 1.0. Sheffield: hriOnline, 2007. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Thornbury, Walter. Old and New London. 6 vols. London, 1878. Reprint. British History Online. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Velten, Hannah. Beastly London: A History of Animals in the City. London: Reaktion Books, 2013.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

This item is cited in the following documents:

Cite this page

MLA citation

.

City Dog House.The Map of Early Modern London, edited by , U of Victoria, 20 Jun. 2018, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/CITY1.htm.

Chicago citation

.

City Dog House.The Map of Early Modern London. Ed. . Victoria: University of Victoria. Accessed June 20, 2018. http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/CITY1.htm.

APA citation

2018. City Dog House. In (Ed), The Map of Early Modern London. Victoria: University of Victoria. Retrieved from http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/CITY1.htm.

RIS file (for RefMan, EndNote etc.)

Provider: University of Victoria Database: The Map of Early Modern London Content: text/plain; charset="utf-8" TY - ELEC A1 - Casebeer, Kate ED - Jenstad, Janelle T1 - City Dog House T2 - The Map of Early Modern London PY - 2018 DA - 2018/06/20 CY - Victoria PB - University of Victoria LA - English UR - http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/CITY1.htm UR - http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/xml/standalone/CITY1.xml ER -

RefWorks

RT Web Page SR Electronic(1) A1 Casebeer, Kate A6 Jenstad, Janelle T1 City Dog House T2 The Map of Early Modern London WP 2018 FD 2018/06/20 RD 2018/06/20 PP Victoria PB University of Victoria LA English OL English LK http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/CITY1.htm

TEI citation

<bibl type="mla"><author><name ref="#CASE1"><surname>Casebeer</surname>, <forename>Kate</forename></name></author>. <title level="a">City Dog House</title>. <title level="m">The Map of Early Modern London</title>, edited by <editor><name ref="#JENS1"><forename>Janelle</forename> <surname>Jenstad</surname></name></editor>, <publisher>U of Victoria</publisher>, <date when="2018-06-20">20 Jun. 2018</date>, <ref target="http://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/CITY1.htm">mapoflondon.uvic.ca/CITY1.htm</ref>.</bibl>Personography

-

Janelle Jenstad

JJ

Janelle Jenstad, associate professor in the department of English at the University of Victoria, is the general editor and coordinator of The Map of Early Modern London. She is also the assistant coordinating editor of Internet Shakespeare Editions. She has taught at Queen’s University, the Summer Academy at the Stratford Festival, the University of Windsor, and the University of Victoria. Her articles have appeared in the Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Early Modern Literary Studies, Elizabethan Theatre, Shakespeare Bulletin: A Journal of Performance Criticism, and The Silver Society Journal. Her book chapters have appeared (or will appear) in Performing Maternity in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2007), Approaches to Teaching Othello (Modern Language Association, 2005), Shakespeare, Language and the Stage, The Fifth Wall: Approaches to Shakespeare from Criticism, Performance and Theatre Studies (Arden/Thomson Learning, 2005), Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society (Brill, 2004), New Directions in the Geohumanities: Art, Text, and History at the Edge of Place (Routledge, 2011), and Teaching Early Modern English Literature from the Archives (MLA, forthcoming). She is currently working on an edition of The Merchant of Venice for ISE and Broadview P. She lectures regularly on London studies, digital humanities, and on Shakespeare in performance.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Stub

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

Author of Textual Introduction

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Course Instructor

-

Course Supervisor

-

Course supervisor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Structure and Toponyms)

-

Final Markup Editor

-

GIS Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Modern)

-

Geographical Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Main Transcriber

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Name Encoder

-

Peer Reviewer

-

Primary Author

-

Project Director

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Reviser

-

Second Author

-

Second Encoder

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Janelle Jenstad is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Janelle Jenstad is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Tye Landels-Gruenewald

TLG

Research assistant, 2013-15, and data manager, 2015 to present. Tye completed his undergraduate honours degree in English at the University of Victoria in 2015.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

MoEML Researcher

-

Name Encoder

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

Contributions by this author

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kim McLean-Fiander

KMF

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach, 2015–present; Associate Project Director, 2015–present; Assistant Project Director, 2013-2014; MoEML Research Fellow, 2013. Kim McLean-Fiander comes to The Map of Early Modern London from the Cultures of Knowledge digital humanities project at the University of Oxford, where she was the editor of Early Modern Letters Online, an open-access union catalogue and editorial interface for correspondence from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. She is currently Co-Director of a sister project to EMLO called Women’s Early Modern Letters Online (WEMLO). In the past, she held an internship with the curator of manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library, completed a doctorate at Oxford on paratext and early modern women writers, and worked a number of years for the Bodleian Libraries and as a freelance editor. She has a passion for rare books and manuscripts as social and material artifacts, and is interested in the development of digital resources that will improve access to these materials while ensuring their ongoing preservation and conservation. An avid traveler, Kim has always loved both London and maps, and so is particularly delighted to be able to bring her early modern scholarly expertise to bear on the MoEML project.Roles played in the project

-

Associate Project Director

-

Author

-

Author of MoEML Introduction

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Contributor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Contributor

-

Data Manager

-

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (People)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Managing Editor

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Research Fellow

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Second Author

-

Secondary Author

-

Secondary Editor

-

Toponymist

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Kim McLean-Fiander is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Kim McLean-Fiander is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Joey Takeda

JT

Programmer, 2018-present; Junior Programmer, 2015 to 2017; Research Assistant, 2014 to 2017. Joey Takeda is an MA student at the University of British Columbia in the Department of English (Science and Technology research stream). He completed his BA honours in English (with a minor in Women’s Studies) at the University of Victoria in 2016. His primary research interests include diasporic and indigenous Canadian and American literature, critical theory, cultural studies, and the digital humanities.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Stub

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Date Encoder

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Bibliography)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Agas)

-

Junior Programmer

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Encoder

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Second Author

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Editor

Contributions by this author

Joey Takeda is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Joey Takeda is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Katie Tanigawa

KT

Katie Tanigawa is a doctoral candidate at the University of Victoria. Her dissertation focuses on representations of poverty in Irish modernist literature. Her additional research interests include geospatial analyses of modernist texts and digital humanities approaches to teaching and analyzing literature.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Conceptor

-

Encoder

-

GIS

-

Managing Editor

-

Markup Editor

-

Name Encoder

-

Project Manager

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Second Author

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Katie Tanigawa is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Katie Tanigawa is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Martin D. Holmes

MDH

Programmer at the University of Victoria Humanities Computing and Media Centre (HCMC). Martin ported the MOL project from its original PHP incarnation to a pure eXist database implementation in the fall of 2011. Since then, he has been lead programmer on the project and has also been responsible for maintaining the project schemas. He was a co-applicant on MoEML’s 2012 SSHRC Insight Grant.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of abstract

-

Conceptor

-

Encoder

-

Name Encoder

-

Post-conversion and Markup Editor

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

Contributions by this author

Martin D. Holmes is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Martin D. Holmes is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Ian MacInnes

Ian MacInnes (B.A. Swarthmore College, Ph.D. University of Virginia) is the director of pedagogical partnerships (US) for MoEML. He is Professor of English at Albion College, Michigan, where he teaches Elizabethan literature, Shakespeare, and Milton. His scholarship focuses on representations of animals and the environment in Renaissance literature, particularly in Shakespeare. He has published essays on topics such as horse breeding and geohumoralism in Henry V and on invertebrate bodies in Hamlet. He is particularly interested in teaching methods that rely on students’ curiosity and sense of play.Click here for Ian MacInnes’ Albion College profile.Roles played in the project

-

Guest Editor

-

Supervisor

-

Transcriber

Ian MacInnes is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kate Casebeer

KMC

Student contributor at Albion College, working under the guest editorship of Ian MacInnes.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Encoder

-

Toponymist

Contributions by this author

Kate Casebeer is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Thomas Dekker is mentioned in the following documents:

-

George Gascoigne is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Strype

(b. 1643, d. 1737)Historian and author of The Survey of London, a revised version of Stow’s Survey.John Strype is mentioned in the following documents:

Locations

-

Moorfields is mentioned in the following documents:

-

The Wall

Originally built as a Roman fortification for the provincial city of Londinium in the second century C.E., the London Wall remained a material and spatial boundary for the city throughout the early modern period. Described by Stow ashigh and great,

the London Wall dominated the cityscape and spatial imaginations of Londoners for centuries. Increasingly, the eighteen-foot high wall created a pressurized constraint on the growing city; the various gates functioned as relief valves where development spilled out to occupy spacesoutside the wall.

The Wall is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Mallow Field is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Finsbury Field

Finsbury Field is located in northen London outside the The Wall. Note that MoEML correctly locates Finsbury Field, which the label on the Agas map confuses with Mallow Field (Prockter 40). Located nearby is Finsbury Court. Finsbury Field is outside of the city wards within the borough of Islington(Mills 81).Finsbury Field is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Finsbury Court is mentioned in the following documents:

-

St. Giles (Cripplegate)

For information about St. Giles, Cripplegate, a modern map marking the site where the it once stood, and a walking tour that will take you to the site, visit the Shakespearean London Theatres (ShaLT) article on St. Giles, Cripplegate.St. Giles (Cripplegate) is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Lombard Street

Lombard Street runs east to west from Gracechurch Street to Poultry. The Agas map labels itLombard streat.

Lombard Street limns the south end of Langbourn Ward, but borders three other wards: Walbrook Ward to the south east, Bridge Within Ward to the south west, and Candlewick Street Ward to the south.Lombard Street is mentioned in the following documents:

Organizations

-

Corporation of London

The Corporation of London was the municipal government for the City of London, made up of the Mayor of London, the Court of Aldermen, and the Court of Common Council. It exists today in largely the same form. (TL)Roles played in the project

-

Author

Contributions by this author

This organization is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Mayor of London

The Mayor (or Lord Mayor) of London is an office occupied annually by a new mayor. For the purposes of recording the authorship of mayoral proclamations, MoEML distinguishes between the office of the mayor and the person elected to the office for the year.Roles played in the project

-

Author

Contributions by this author

This organization is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Variant spellings

-

Documents using the spelling

City Dog House

-

Documents using the spelling

Dog House

-

Documents using the spelling

Dog-house

-

Documents using the spelling

dog-house

-

Documents using the spelling

Dogge hous

-

Documents using the spelling

Dogge hous’e

-

Documents using the spelling

dogge-house

-

Documents using the spelling

Lord Maiors dog-house

-

Documents using the spelling

Lord Mayors Dog-house

-

Documents using the spelling

Lord Mayors dogge-house

-

Documents using the spelling

Lord Mayor’s dog house

-

Documents using the spelling

Lord Mayor’s Dog House

-

Documents using the spelling

Lord Mayor’s Dog-kennel