Smithfield

¶Location

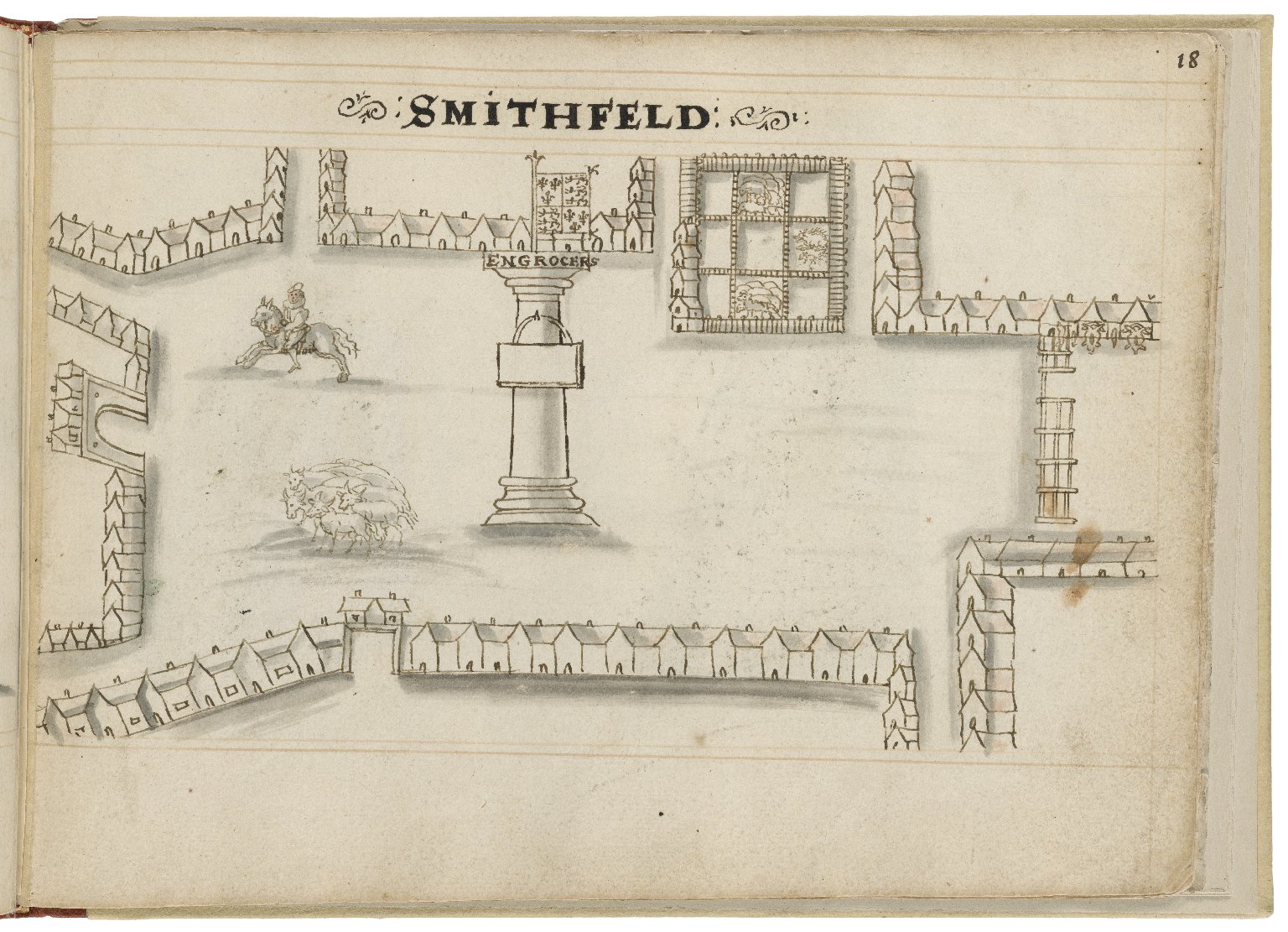

Smithfield is located in Faringdon Without Ward, which was the farthest ward westward of London, right outside the city walls. Initially the large open pasture, from which the locality

receives its name, stretched to the eastern bank of the River Fleet. One of the main streets that ran through Smithfield to Aldersgate was Long Lane. According to Stow,

from long lane ende to the Bars is inclosed with Innes, Brewhouses, and large tenements(Stow 1598, sig. X4r). From the Elms, Smithfield extended from Bow Lane to Holborn to Cow Lane, ending where Cock Lane met Pie Corner (Stow 1598, sig. U8v).

¶Name and Etymology

Smithfield is believed to be a corruption of the name

Smethefeld,originally

Smethefelda,meaning

smooth or level fieldfrom the Old English smethe, and feld (Mills).

¶Name and Etymology

The availability of land for grazing, and its close proximity to both the Turnmill Brook segment of the River Fleet1 and Smithfield Pond, made Smithfield the ideal location to carry out all kinds of commerce related to livestock, hence

street names such as Chick Lane, Cow Lane, and Pie Corner (Thornbury). To the west of Long Lane, there were large pens where sheep were kept until market days. Past Cowbridge was Smithfield Pond, which, according to Stow, was called Horsepool during the Middle Ages because as knights rode through Smithfield, their horses would stop to drink from the pond (Thornbury). The watering hole, because of its location, very quickly evolved into a renowned

horse-market known as Smithfield Market.

The horse market at Smithfield subsequently became the informal hub of the livestock trade. This concentration of

livestock in turn attracted both cloth merchants and butchers. In an 1174 letter, William Fitzstephen, clerk to Thomas Becket, describes the site as a

smooth field where every Friday there is a celebrated rendezvous of fine horses to be sold, and in another quarter are placed vendible of the peasant, swine with their deep flanks, and cows and oxen of immense bulk(

History of Smithfield Market).

¶History

Throughout the Middle Ages, monarchs frequently used the great open spaces of Smithfield for tournaments (Richardson). During his reign, Edward III hosted several jousting tournaments at Smithfield. In 1357

great and royall Iusts were then holden in Smithfieldwhich were attended by the kings of France and Scotland (Stow 1633, sig. 2O1r). In 1362, Edward III held a tournament during the first five days of May which was attended by the French king and knights from Spain, Cyprus and Armenia. One of the largest tournaments was hosted by Richard II. By Stow’s estimate, sixty knights and ladies were in attendance (Stow 1633, sig. 2O1r). The knights paraded from the Tower of London to Smithfield with their squires and ladies in tow. The tournament and subsequent feasting lasted several days (Thornbury).

In the time of Henry V, beyond Turnemill Brooke, a new building, called the Elms was constructed. The building was so named for the prominent forest of elm trees

that grew nearby. Here, many executions took place.

In addition, the Smithfield greens were also used to settle disputes between gentlemen via duel or ordeal by

battle (Thornbury). Often the men battled to the point where one could kill the other. When such an

occasion arose, the king would then stop the fight and forgive them both (Stow 1633, sig. 2O1v).

In 1381, Smithfield was used as a meeting place for the Peasant’s Revolt. The Revolt, lead by Wat Tyler, was caused by economic and social unrest following the devastating outbreak of plague

in 1348 and increasing frustration at the exorbitantly high tax rates mandated in order to

fund the Hundred Years War. On 15 June, Wat Tyler and his rebels met with Richard II and his men at Smithfield to negotiate (Thornbury). When Wat Tyler and the rebels refused to disarm in the presence of the king, a battle ensued (Richardson). During the fight, Tyler was stabbed in the throat by the Lord Mayor of London, William Walworth (Thornbury). After Tyler’s death, the rebellion effectively came to an end.

In addition to being ideal for grazing and tournaments, the open space in Smithfield also proved to be an ideal venue for the staging of public executions. Criminals

and heretics were burned, boiled or hanged on Smithfield’s grounds before the gallows were moved to Tyburn during the reign of Henry IV (Thornbury). In 1305, Sir William Wallace, who fought for Scotland’s independence and inspired the film Braveheart, was executed at the Elms on the eve of the fair of St. Bartholomew. Accused of high treason, Wallace was dragged from Westminster Hall to Smithfield Market. Here, he was hung, drawn and quartered. Wallace was then

emasculated, eviscerated, beheaded, then divided into four parts (the four horrors) Gap in transcription. Reason: (SM)[…] His head was placed on a pike atop London Bridge, which was later joined by the heads of his brother, John, and Sir Simon Fraser. His limbs were displayed, separately, in Newcastle, Berwick, Stirling, and Perth(Richardson).

Near the end of Henry VIII’s reign, two highly discussed executions took place at Smithfield. Anne Askew, who mingled with aristocracy, and Nicholas Shaxton, bishop of Salisbury, were burned at the stake for their heretical denial of the

presence of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament during Mass (

Bartholomew Fair and Smithfield). Subsequently, during Queen Mary’s reign, a great many of her 277 Protestant victims were burned at the stake in Smithfield. Queen Elizabeth’s likewise ordered the execution of a number of Anabaptists on the very same grounds (Thornbury).

Despite its notoriously bloody character, the Smithfield area is also bound up with a rich religious tradition. The priory of St. Bartholomew the Great was established in Smithfield in 1123 by a monk named Rahere, who had once been Henry I’s court jester and revel-master (Thornbury). Legend said that Rahere underwent a conversion experience when he fell deathly ill on a pilgrimage to Rome.

Approached by St. Bartholomew the Apostle in a dream, he was instructed to build a church in the saint’s name in the suburbs

of London (Thornbury). After a series of miracles occurred at the priory, Henry I established a charter for the church and granted permission for a three day fair

to be held annually, beginning on the feast day of St. Bartholomew (Thornbury). The fair became a staple of London summer activities and thrived until 1855 when it was suppressed due to the abundance

of illicit activities being conducted on the fair grounds. According to Henry Morely,

there were most likely two fairs—one in Smithfield and one just inside the gates of the priory (Thornbury). Due to the cloth fair’s popularity, it very quickly began to attract a variety

of vendors, showmen, and entertainers. At the fair, a visitor could find puppet shows,

wrestling matches, and bull and bear baiting (

Bartholomew Fair and Smithfield).

As a public gathering space, Bartholomew Fair was subject to closure during plague

time. In 1593, Queen Elizabeth cancelled Bartholomew Fair in an effort to curtail transmission of the disease (A proclamation to reforme). She also ordered that the markets be shut down, instructing that the open space

of Smithfield be used only for the selling of livestock and dairy products.

¶Literary References

Three direct references to Smithfield appear in the works of Shakespeare. Falstaff references the Smithfield horse market in Henry IV, Part 2:

Here Falstaff alludes to a proverb found in Simon Robson’s Choise of Change (1585) and Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy (1621). Robson puts the proverb thus:Page: He’s gone into Smithfield, to buy your worship a horse.Falstaff: I bought him in Pauls, and he’ll buy me a horse in Smithfield. An I could get me but a wife in the stews, I were manned, horsed, and wived.(Shakespeare 1.2.322-327)

A man must not make choice of 3. things in 3. places. Of a wife in Westminster. Of a servant in Paules. Of a horse in Smithfield. Least he choose a queane, a knave, or a jade.The other two references appear in Henry VI, Part 2. In 2.3 King Henry VI sentences the witch Margery Jourdain to be burned at the stake in Smithfield:

The witch in Smithfield shall be burnt to ashes(Shakespeare 2.3.7). This detail comes directly from one of Shakespeare’s sources for the play, Edward Hall’s The Union of the Two Noble and Illustre Families of Lancaster and York (1548). In 4.6, Dick the Butcher informs Jack Cade:

My lord, there’s an army gathered together in Smithfield(Shakespeare 4.6.11-12). In the next scene, 4.7, which takes places in Smithfield, Cade and the rebels succeed in defeating this army sent to put down their rebellion.

Perhaps the best know literary treatment of Smithfield appears is in Ben Jonson’s eponymous comedy Bartholomew Fayre. It was first performed by the Lady Elizabeth’s Men on 31 October 1614 at the Hope Theatre, and presented to the court at Whitehall Palace the following day (Campbell). The play chronicles Londoners from all walks of life as they attempt to navigate

the fair and its raucous and unruly world. Largely episodic in structure, the play

lacks any discernible plot or obvious protagonist. Rather, the comedy’s humor depends

upon the vividly drawn setting and evocation of the unique experience of living in

Jacobean London. Fran C. Chalfant points to references in Jonson’s work to Smithfield’s layered history. In Act 4, Bartholomew Cokes

lament[s] his misfortune at the hands of cutpurses(Chalfant). Cokes says,

if ever any Bartholomew had that luck Gap in transcription. Reason: (SM)[…] that I have had, I’ll be martyr’d for him and in Smithfield, too(Jonson 4.2.67-68). Chalfant suggests that

martyr’d at Smithfieldis a reference to Smithfield’s long history of heretical executions.

¶Great Fire

The Great Fire of 1666 sputtered out in Smithfield. The fire stopped at Pie Corner where Cock Lane meets Giltspur Street. The Fortune of War Public House occupied the corner and in commemoration of the end of the fire, a gold en cherub,

meant to represent gluttony, was placed on the outside of the building. Many Londoners

apparently thought that gluttony was the cause of the fire because it started on Pudding Lane and ended at Pie Corner (Conlon).

Notes

- For the purposes of this entry, the particular segment of the River Fleet that flows through Smithfield, designated

Turnmill Brook,

will be used. (SM)↑

References

-

Citation

A proclamation to reforme the disorder in accesse of greater number of persons to the court. London, 1593. STC 8233.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Bartholomew Fair and Smithfield.

Folger Shakespeare Library.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Campbell, Gordon.Introduction.

The Alchemist and Other Plays. Ed. Gordon Campbell. Oxford: Oxford UP. xix-xxi. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Chalfant, Fran C. Ben Jonson’s London: A Jacobean Placename Dictionary. Athens: U of Georgia P, 1978. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Conlon, Katherine.Sites of the Great Fire of London, 1666 - Travel Darkly.

Travel Darkly.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

.

Executions.

The Map of Early Modern London, Edition 7.0, edited by , U of Victoria, 05 May 2022, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/EXEC1.htm. -

Citation

History of Smithfield Market.

City of London. https://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/supporting-businesses/business-support-and-advice/wholesale-markets/smithfield-market/history-of-the-market.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Knowles, Ronald, ed. King Henry VI Part 2. By William Shakespeare. London: Thomas Nelson, 1999. Reprinted by London: Thomson Learning, 2001. Arden Shakespeare. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Mills, A.D. Oxford Dictionary of London Place Names. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2001. Remediated by Oxford Reference.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Richardson, Emily.Smithfield: A Brief History.

Measure.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Shakespeare, William. Henry IV, Part 1. Ed. Rosemary Gaby. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/1H4/.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Thornbury, Walter.Fleet Street: General Introduction.

Old and New London. Vol. 1. London, 1878. 32-53. Remediated by British History Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Thornbury, Walter.Smithfield and Bartholomew Fair.

Old and New London. Vol. 2. London, 1878. 344-351. Remediated by British History Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Thornbury, Walter.Smithfield.

Old and New London. Vol. 2. London, 1878. 339-344. Remediated by British History Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Weinreb, Ben, Christopher Hibbert, Julia Keay, and John Keay. The London Encyclopaedia. 3rd ed. London: Macmillan, 2008. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

Cite this page

MLA citation

.

Smithfield.The Map of Early Modern London, Edition 7.0, edited by , U of Victoria, 05 May 2022, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/SMIT1.htm.

Chicago citation

.

Smithfield.The Map of Early Modern London, Edition 7.0. Ed. . Victoria: University of Victoria. Accessed May 05, 2022. mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/SMIT1.htm.

APA citation

2022. Smithfield. In (Ed), The Map of Early Modern London (Edition 7.0). Victoria: University of Victoria. Retrieved from https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/editions/7.0/SMIT1.htm.

RIS file (for RefMan, RefWorks, EndNote etc.)

Provider: University of Victoria Database: The Map of Early Modern London Content: text/plain; charset="utf-8" TY - ELEC A1 - Mineer, Sydney ED - Jenstad, Janelle T1 - Smithfield T2 - The Map of Early Modern London ET - 7.0 PY - 2022 DA - 2022/05/05 CY - Victoria PB - University of Victoria LA - English UR - https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/SMIT1.htm UR - https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/xml/standalone/SMIT1.xml ER -

TEI citation

<bibl type="mla"><author><name ref="#MINE1"><surname>Mineer</surname>, <forename>Sydney</forename></name></author>.

<title level="a">Smithfield</title>. <title level="m">The Map of Early Modern London</title>,

Edition <edition>7.0</edition>, edited by <editor><name ref="#JENS1"><forename>Janelle</forename>

<surname>Jenstad</surname></name></editor>, <publisher>U of Victoria</publisher>,

<date when="2022-05-05">05 May 2022</date>, <ref target="https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/SMIT1.htm">mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/SMIT1.htm</ref>.</bibl>

Personography

-

Molly Rothwell

MR

Project Manager, 2022-present. Research Assistant, 2020-2022. Molly Rothwell was an undergraduate student at the University of Victoria, with a double major in English and History. During her time at MoEML, Molly primarily worked on encoding and transcribing the 1598 and 1633 editions of Stow’s Survey, adding toponyms to MoEML’s Gazetteer, researching England’s early-modern court system, and standardizing MoEML’s Mapography.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Molly Rothwell is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Molly Rothwell is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kate LeBere

KL

Project Manager, 2020-2021. Assistant Project Manager, 2019-2020. Research Assistant, 2018-2020. Kate LeBere completed her BA (Hons.) in History and English at the University of Victoria in 2020. She published papers in The Corvette (2018), The Albatross (2019), and PLVS VLTRA (2020) and presented at the English Undergraduate Conference (2019), Qualicum History Conference (2020), and the Digital Humanities Summer Institute’s Project Management in the Humanities Conference (2021). While her primary research focus was sixteenth and seventeenth century England, she completed her honours thesis on Soviet ballet during the Russian Cultural Revolution. During her time at MoEML, Kate made significant contributions to the 1598 and 1633 editions of Stow’s Survey of London, old-spelling anthology of mayoral shows, and old-spelling library texts. She authored the MoEML’s first Project Management Manual andquickstart

guidelines for new employees and helped standardize the Personography and Bibliography. She is currently a student at the University of British Columbia’s iSchool, working on her masters in library and information science.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Kate LeBere is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Kate LeBere is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Joey Takeda

JT

Programmer, 2018-present. Junior Programmer, 2015-2017. Research Assistant, 2014-2017. Joey Takeda was a graduate student at the University of British Columbia in the Department of English (Science and Technology research stream). He completed his BA honours in English (with a minor in Women’s Studies) at the University of Victoria in 2016. His primary research interests included diasporic and indigenous Canadian and American literature, critical theory, cultural studies, and the digital humanities.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Junior Programmer

-

Markup Editor

-

Post-Conversion Editor

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Joey Takeda is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Joey Takeda is mentioned in the following documents:

Joey Takeda authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Jenstad, Janelle and Joseph Takeda.

Making the RA Matter: Pedagogy, Interface, and Practices.

Making Things and Drawing Boundaries: Experiments in the Digital Humanities. Ed. Jentery Sayers. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2018. Print.

-

-

Tye Landels-Gruenewald

TLG

Data Manager, 2015-2016. Research Assistant, 2013-2015. Tye completed his undergraduate honours degree in English at the University of Victoria in 2015.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kim McLean-Fiander

KMF

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach, 2015–2020. Associate Project Director, 2015. Assistant Project Director, 2013-2014. MoEML Research Fellow, 2013. Kim McLean-Fiander comes to The Map of Early Modern London from the Cultures of Knowledge digital humanities project at the University of Oxford, where she was the editor of Early Modern Letters Online, an open-access union catalogue and editorial interface for correspondence from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. She is currently Co-Director of a sister project to EMLO called Women’s Early Modern Letters Online (WEMLO). In the past, she held an internship with the curator of manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library, completed a doctorate at Oxford on paratext and early modern women writers, and worked a number of years for the Bodleian Libraries and as a freelance editor. She has a passion for rare books and manuscripts as social and material artifacts, and is interested in the development of digital resources that will improve access to these materials while ensuring their ongoing preservation and conservation. An avid traveler, Kim has always loved both London and maps, and so is particularly delighted to be able to bring her early modern scholarly expertise to bear on the MoEML project.Roles played in the project

-

Associate Project Director

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Managing Editor

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Research Fellow

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Kim McLean-Fiander is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Kim McLean-Fiander is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Janelle Jenstad

JJ

Janelle Jenstad is Associate Professor of English at the University of Victoria, Director of The Map of Early Modern London, and PI of Linked Early Modern Drama Online. She has taught at Queen’s University, the Summer Academy at the Stratford Festival, the University of Windsor, and the University of Victoria. With Jennifer Roberts-Smith and Mark Kaethler, she co-edited Shakespeare’s Language in Digital Media (Routledge). She has prepared a documentary edition of John Stow’s A Survey of London (1598 text) for MoEML and is currently editing The Merchant of Venice (with Stephen Wittek) and Heywood’s 2 If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody for DRE. Her articles have appeared in Digital Humanities Quarterly, Renaissance and Reformation,Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Early Modern Literary Studies, Elizabethan Theatre, Shakespeare Bulletin: A Journal of Performance Criticism, and The Silver Society Journal. Her book chapters have appeared (or will appear) in Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society (Brill, 2004), Shakespeare, Language and the Stage, The Fifth Wall: Approaches to Shakespeare from Criticism, Performance and Theatre Studies (Arden/Thomson Learning, 2005), Approaches to Teaching Othello (Modern Language Association, 2005), Performing Maternity in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2007), New Directions in the Geohumanities: Art, Text, and History at the Edge of Place (Routledge, 2011), Early Modern Studies and the Digital Turn (Iter, 2016), Teaching Early Modern English Literature from the Archives (MLA, 2015), Placing Names: Enriching and Integrating Gazetteers (Indiana, 2016), Making Things and Drawing Boundaries (Minnesota, 2017), and Rethinking Shakespeare’s Source Study: Audiences, Authors, and Digital Technologies (Routledge, 2018).Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Author (Preface)

-

Author of Preface

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Course Instructor

-

Course Supervisor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Peer Reviewer

-

Project Director

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Janelle Jenstad is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Janelle Jenstad is mentioned in the following documents:

Janelle Jenstad authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Jenstad, Janelle and Joseph Takeda.

Making the RA Matter: Pedagogy, Interface, and Practices.

Making Things and Drawing Boundaries: Experiments in the Digital Humanities. Ed. Jentery Sayers. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2018. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Building a Gazetteer for Early Modern London, 1550-1650.

Placing Names. Ed. Merrick Lex Berman, Ruth Mostern, and Humphrey Southall. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 2016. 129-145. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

The Burse and the Merchant’s Purse: Coin, Credit, and the Nation in Heywood’s 2 If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody.

The Elizabethan Theatre XV. Ed. C.E. McGee and A.L. Magnusson. Toronto: P.D. Meany, 2002. 181–202. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Early Modern Literary Studies 8.2 (2002): 5.1–26..The City Cannot Hold You

: Social Conversion in the Goldsmith’s Shop. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

The Silver Society Journal 10 (1998): 40–43.The Gouldesmythes Storehowse

: Early Evidence for Specialisation. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Lying-in Like a Countess: The Lisle Letters, the Cecil Family, and A Chaste Maid in Cheapside.

Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 34 (2004): 373–403. doi:10.1215/10829636–34–2–373. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Public Glory, Private Gilt: The Goldsmiths’ Company and the Spectacle of Punishment.

Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society. Ed. Anne Goldgar and Robert Frost. Leiden: Brill, 2004. 191–217. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Smock Secrets: Birth and Women’s Mysteries on the Early Modern Stage.

Performing Maternity in Early Modern England. Ed. Katherine Moncrief and Kathryn McPherson. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007. 87–99. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Using Early Modern Maps in Literary Studies: Views and Caveats from London.

GeoHumanities: Art, History, Text at the Edge of Place. Ed. Michael Dear, James Ketchum, Sarah Luria, and Doug Richardson. London: Routledge, 2011. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Versioning John Stow’s A Survey of London, or, What’s New in 1618 and 1633?.

Janelle Jenstad Blog. https://janellejenstad.com/2013/03/20/versioning-john-stows-a-survey-of-london-or-whats-new-in-1618-and-1633/. -

Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. Ed. Janelle Jenstad. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/MV/.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ & nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. Ed. Janelle Jenstad and the MoEML Team. MoEML. Transcribed.

-

-

Martin D. Holmes

MDH

Programmer at the University of Victoria Humanities Computing and Media Centre (HCMC). Martin ported the MOL project from its original PHP incarnation to a pure eXist database implementation in the fall of 2011. Since then, he has been lead programmer on the project and has also been responsible for maintaining the project schemas. He was a co-applicant on MoEML’s 2012 SSHRC Insight Grant.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Conceptor

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Post-Conversion Editor

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

Contributions by this author

Martin D. Holmes is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Martin D. Holmes is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Anita Sherman

Anita Gilman Sherman is a MoEML Pedagogical Partner. She is an Associate Professor in the Department of Literature at American University. She is the author of Skepticism and Memory in Shakespeare and Donne (2007). She has published articles on several topics, including essays on Garcilaso de la Vega, Montaigne, Thomas Heywood, John Donne, Shakespeare and W. G. Sebald. Her current book project is titled The Skeptical Imagination: Paradoxes of Secularization in English Literature, 1579-1681.Roles played in the project

-

Guest Editor

Anita Sherman is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Sydney Mineer

SM

Student contributor enrolled in Literature 434: Revenge Drama and City Comedy at American University in Fall 2014, working under the guest editorship of Anita Sherman.Roles played in the project

-

Author

Contributions by this author

Sydney Mineer is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Sydney Mineer is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Hugh Alley

Author.Hugh Alley is mentioned in the following documents:

Hugh Alley authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Alley, Hugh. Hugh Alley’s Caveat: The Markets of London in 1598: Folger MS V.a. 318. Ed. Ian Archer, Caroline Barron, and Vanessa Harding. London: London Topographical Society, 1988. Print.

-

Jack Cade is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Edward III

Edward This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 3III King of England

(b. 12 November 1312, d. 21 June 1377)Edward III is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 1I Queen of England Queen of Ireland Gloriana Good Queen Bess

(b. 7 September 1533, d. 24 March 1603)Queen of England and Ireland 1558-1603.Elizabeth I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Falstaff

Dramatic character in William Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part 1, Henry IV, Part 2, and The Merry Wives of Windsor. Mentioned in Henry V.Falstaff is mentioned in the following documents:

-

William fitz-Stephen is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Edward Hall is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Margery Jourdain

Dramatic character in William Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part 2.Margery Jourdain is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Dick the Butcher

Dramatic character in William Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part 2.Dick the Butcher is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Bardolph is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Henry VIII

Henry This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 8VIII King of England King of Ireland

(b. 28 June 1491, d. 28 January 1547)King of England and Ireland 1509-1547.Henry VIII is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Henry VI

Henry This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 6VI King of England

(b. 6 December 1421, d. 21 May 1471)Henry VI is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Henry V

Henry This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 5V King of England

(b. 1386, d. 1422)Henry V is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Ben Jonson is mentioned in the following documents:

Ben Jonson authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Chapman, George, Ben Jonson, and John Marston. Eastvvard hoe. London: George Eld for William Aspley, 1605. STC 4973.

-

Chapman, George, Ben Jonson, and John Marston. Eastward Ho! Ed. R.W. Van Fossen. New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Print.

-

Dekker, Thomas, Stephen Harrison, Ben Jonson, and Thomas Middleton. The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment of King James through the City of London, 15 March 1604, with the Arches of Triumph. Ed. R. Malcolm Smuts. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 219–279. Print.

-

Gifford, William, ed. The Works of Ben Jonson. By Ben Jonson. Vol. 1. London: Nichol, 1816. Remediated by Internet Archive.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Alchemist. London: New Mermaids, 1991. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Bartholomew Fair. Ed. E.A. Horsman. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1979. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Bartholomew Fair. Ed. Suzanne Gossett, based on The Revels Plays edition ed. E.A. Horsman. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2000. Revels Student Editions. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Ben: Ionson’s execration against Vulcan. London: J. Okes for John Benson and A. Crooke, 1640. STC 14771.

-

Jonson, Ben. B. Ion: his part of King Iames his royall and magnificent entertainement through his honorable cittie of London, Thurseday the 15. of March. 1603 so much as was presented in the first and last of their triumphall arch’s. London, 1604. STC 14756.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Complete Poetry of Ben Jonson. Ed. William B. Hunter, Jr. New York: New York UP, 1963. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Complete Poetry of Ben Jonson. Ed. William B. Hunter. Stuart Edtions. New York: New YorkUP, 1963.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Devil is an Ass. Ed. Peter Happé. Manchester and New York: Manchester UP, 1996. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Epicene. Ed. Richard Dutton. Revels Plays. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2004. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Every Man Out of His Humour. Ed. Helen Ostovich. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2001. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. The First, of Blacknesse, Personated at the Court, at White-hall, on the Twelfth Night, 1605. The Characters of Two Royall Masques: The One of Blacknesse, the Other of Beautie. Personated by the Most Magnificent of Queenes Anne Queene of Great Britaine, &c. with her Honorable Ladyes, 1605 and 1608 at White-hall. London : For Thomas Thorp, and are to be Sold at the Signe of the Tigers Head in Paules Church-yard, 1608. Sig. A3r-C2r. STC 14761.

-

Jonson, Ben. Oberon, The Faery Prince. The Workes of Benjamin Jonson. Vol. 1. London: Will Stansby, 1616. Sig. 4N2r-2N6r.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Staple of Newes. The Works. Vol. 2. London: Printed by I.B. for Robert Allot, 1631. Sig. 2A1r-2J2v.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Staple of News. Ed. Anthony Parr. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben.

To Penshurst.

The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt, Carol T. Christ, Alfred David, Barbara K. Lewalski, Lawrence Lipking, George M. Logan, Deidre Shauna Lynch, Katharine Eisaman Maus, James Noggle, Jahan Ramazani, Catherine Robson, James Simpson, Jon Stallworthy, Jack Stillinger, and M. H. Abrams. 9th ed. Vol. B. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2012. 1547. -

Jonson, Ben. Underwood. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1905. Remediated by Internet Archive.

-

Jonson, Ben. The vvorkes of Beniamin Ionson. Containing these playes, viz. 1 Bartholomew Fayre. 2 The staple of newes. 3 The Divell is an asse. London, 1641. STC 14754.

-

Mary I

Mary This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 1I Queen of England Queen of Ireland

(b. 18 February 1516, d. 17 November 1558)Mary I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Bartholomew Cokes

Dramatic character in Ben Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair.Bartholomew Cokes is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Richard II

Richard This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 2II King of England

(b. 6 January 1367, d. 1400)Richard II is mentioned in the following documents:

-

William Shakespeare is mentioned in the following documents:

William Shakespeare authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. 1998. Remediated by Project Gutenberg.

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. Ed. Vittorio Gabrieli and Giorgio Melchiori. Revels Plays. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1990. Print.

-

Shakespeare, William. All’s Well That Ends Well. Ed. Helen Ostovich. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/AWW/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Antony and Cleopatra. Ed. Randall Martin. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Ant/.

-

Shakespeare, William. As You Like It. Ed. David Bevington. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/AYL/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Comedy of Errors. Ed. Matthew Steggle. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Err/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Coriolanus. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Cor/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Cymbeline. Ed. Jennifer Forsyth. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Cym/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Edward III. Ed. Jennifer Massai. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Edw/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The first part of the contention betwixt the two famous houses of Yorke and Lancaster with the death of the good Duke Humphrey: and the banishment and death of the Duke of Suffolke, and the tragicall end of the proud Cardinall of VVinchester, vvith the notable rebellion of Iacke Cade: and the Duke of Yorkes first claime vnto the crowne. London, 1594. STC 26099.

-

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. Ed. David Bevington. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Ham/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry IV, Part 1. Ed. Rosemary Gaby. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/1H4/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry IV, Part 2. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/2H4/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry V. Ed. James D. Mardock. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/H5/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry VIII. Ed. Diane Jakacki. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/H8/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry VI, Part 1. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/1H6/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry VI, Part 2. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/2H6/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry VI, Part 3. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/3H6/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Julius Caesar. Ed. John D. Cox. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/JC/.

-

Shakespeare, William. King John. Ed. Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Jn/.

-

Shakespeare, William. King Lear. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 1201–54.

-

Shakespeare, William. King Lear. Ed. Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Lr/.

-

Shakespeare, William. King Richard III. Ed. James R. Siemon. London: Methuen, 2009. The Arden Shakespeare.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Life of King Henry the Eighth. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 919–64.

-

Shakespeare, William. A Lover’s Complaint. Ed. Hardy M. Cook. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/lC/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Love’s Labor’s Lost. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/LLL/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Macbeth. Ed. Anthony Dawson. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Mac/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Measure for Measure. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 414–454.

-

Shakespeare, William. Measure for Measure. Ed. Herbert Weil. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/MM/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. Ed. Janelle Jenstad. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/MV/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Merry Wives of Windsor. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Wiv/.

-

Shakespeare, William. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Ed. Suzanne Westfall. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/MND/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Mr. VVilliam Shakespeares comedies, histories, & tragedies Published according to the true originall copies. London, 1623. STC 22273.

-

Shakespeare, William. Much Ado About Nothing. Ed. Grechen Minton. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Ado/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Othello. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Oth/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Passionate Pilgrim. Ed. Hardy M. Cook. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/PP/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Pericles. Ed. Tom Bishop. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Per/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Phoenix and the Turtle. Ed. Hardy M. Cook. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/PhT/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Rape of Lucrece. Ed. Hardy M. Cook. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Luc/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Richard II. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 740–83.

-

Shakespeare, William. Richard II. Ed. Catherine Lisak. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/R2/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Richard the Third (Modern). Ed. Adrian Kiernander. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/R3/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Romeo and Juliet. Ed. Erin Sadlack. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Rom/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Second Part of King Henry the Sixth. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 552–984.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Sonnets. Ed. Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Son/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Taming of the Shrew. Ed. Erin Kelly. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Shr/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Tempest. Ed. Brent Whitted and Paul Yachnin. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Tmp/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Timon of Athens. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Tim/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Titus Andronicus. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 966–1004.

-

Shakespeare, William. Titus Andronicus. Ed. Trey Jansen. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Tit/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Troilus and Cressida. Ed. W. L. Godshalk. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Tro/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Twelfth Night. Ed. David Carnegie and Mark Houlahan. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/TN/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Two Gentlemen of Verona. Ed. Melissa Walter. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/TGV/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Two Noble Kinsmen. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/TNK/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Venus and Adonis. Ed. Hardy M. Cook. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Ven/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Winter’s Tale. Ed. Hardin Aasand. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/WT/.

-

John Stow

(b. between 1524 and 1525, d. 1605)Historian and author of A Survey of London. Husband of Elizabeth Stow.John Stow is mentioned in the following documents:

John Stow authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Blome, Richard.

Aldersgate Ward and St. Martins le Grand Liberty Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. M3r and sig. M4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Aldgate Ward with its Division into Parishes. Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections & Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H3r and sig. H4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Billingsgate Ward and Bridge Ward Within with it’s Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. Y2r and sig. Y3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Bishopsgate-street Ward. Taken from the Last Survey and Corrected.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. N1r and sig. N2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Bread Street Ward and Cardwainter Ward with its Division into Parishes Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. B3r and sig. B4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Broad Street Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections and Additions, & Cornhill Ward with its Divisions into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, &c.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. P2r and sig. P3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Cheape Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig.D1r and sig. D2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Coleman Street Ward and Bashishaw Ward Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. G2r and sig. G3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Cow Cross being St Sepulchers Parish Without and the Charterhouse.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H2v and sig. H3r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Creplegate Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, with Additions, and Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. I3r and sig. I4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Farrington Ward Without, with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections & Amendments.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. 2F3r and sig. 2F4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Lambeth and Christ Church Parish Southwark. Taken from ye last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. Z1r and sig. Z2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Langborne Ward with its Division into Parishes. Corrected from the Last Survey. & Candlewick Ward with its Division into Parishes. Corrected from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. U3r and sig. U4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Map of St. Gilles’s Cripple Gate. Without. With Large Additions and Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H2v and sig. H3r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Map of the Parish of St. Dunstans Stepney, als. Stebunheath Divided into Hamlets.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. F3r and sig. F4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Map of the Parish of St Mary White Chappel and a Map of the Parish of St Katherines by the Tower.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. F2r and sig. F3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of Lime Street Ward. Taken from ye Last Surveys & Corrected.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. M1r and sig. M2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of St. Andrews Holborn Parish as well Within the Liberty as Without.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. 2I1r and sig. 2I2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parishes of St. Clements Danes, St. Mary Savoy; with the Rolls Liberty and Lincolns Inn, Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig.O4v and sig. O1r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St. Anns. Taken from the last Survey, with Correction, and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. L2v and sig. L3r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St. Giles’s in the Fields Taken from the Last Servey, with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. K1v and sig. K2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Margarets Westminster Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig.H3v and sig. H4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Martins in the Fields Taken from ye Last Survey with Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. I1v and sig. I2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Pauls Covent Garden Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. L3v and sig. L4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Saviours Southwark and St Georges taken from ye last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. D1r and sig.D2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

The Parish of St. James Clerkenwell taken from ye last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H3v and sig. H4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

The Parish of St. James’s, Westminster Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. K4v and sig. L1r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

The Parish of St Johns Wapping. The Parish of St Paul Shadwell.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. E2r and sig. E3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Portsoken Ward being Part of the Parish of St. Buttolphs Aldgate, taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. B1v and sig. B2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Queen Hith Ward and Vintry Ward with their Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. 2C4r and sig. 2D1v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Shoreditch Norton Folgate, and Crepplegate Without Taken from ye Last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. G1r and sig. G2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Spittle Fields and Places Adjacent Taken from ye Last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. F4r and sig. G1v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

St. Olave and St. Mary Magdalens Bermondsey Southwark Taken from ye last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. C2r and sig.C3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Tower Street Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. E2r and sig. E3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Walbrook Ward and Dowgate Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Surveys.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. 2B3r and sig. 2B4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

The Wards of Farington Within and Baynards Castle with its Divisions into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. Q2r and sig. Q3v. [See more information about this map.] -

The City of London as in Q. Elizabeth’s Time.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Frontispiece. -

A Map of the Tower Liberty.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H4v and sig. I1r. [See more information about this map.] -

A New Plan of the City of London, Westminster and Southwark.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Frontispiece. -

Pearl, Valerie.

Introduction.

A Survey of London. By John Stow. Ed. H.B. Wheatley. London: Everyman’s Library, 1987. v–xii. Print. -

Pullen, John.

A Map of the Parish of St Mary Rotherhith.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. Z3r and sig. Z4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Stow, John. The abridgement of the English Chronicle, first collected by M. Iohn Stow, and after him augmented with very many memorable antiquities, and continued with matters forreine and domesticall, vnto the beginning of the yeare, 1618. by E.H. Gentleman. London, Edward Allde and Nicholas Okes, 1618. STC 23332.

-

Stow, John. The annales of England Faithfully collected out of the most autenticall authors, records, and other monuments of antiquitie, lately collected, since encreased, and continued, from the first habitation vntill this present yeare 1605. London: Peter Short, Felix Kingston, and George Eld, 1605. STC 23337.

-

Stow, John, Anthony Munday, and Henry Holland. THE SVRVAY of LONDON: Containing, The Originall, Antiquitie, Encrease, and more Moderne Estate of the sayd Famous Citie. As also, the Rule and Gouernment thereof (both Ecclesiasticall and Temporall) from time to time. With a briefe Relation of all the memorable Monuments, and other especiall Obseruations, both in and about the same CITIE. Written in the yeere 1598. by Iohn Stow, Citizen of London. Since then, continued, corrected and much enlarged, with many rare and worthy Notes, both of Venerable Antiquity, and later memorie; such, as were neuer published before this present yeere 1618. London: George Purslowe, 1618. STC 23344. Yale University Library copy.

-

Stow, John, Anthony Munday, and Humphrey Dyson. THE SURVEY OF LONDON: CONTAINING The Original, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of that City, Methodically set down. With a Memorial of those famouser Acts of Charity, which for publick and Pious Vses have been bestowed by many Worshipfull Citizens and Benefactors. As also all the Ancient and Modern Monuments erected in the Churches, not only of those two famous Cities, LONDON and WESTMINSTER, but (now newly added) Four miles compass. Begun first by the pains and industry of John Stow, in the year 1598. Afterwards inlarged by the care and diligence of A.M. in the year 1618. And now compleatly finished by the study &labour of A.M., H.D. and others, this present year 1633. Whereunto, besides many Additions (as appears by the Contents) are annexed divers Alphabetical Tables, especially two, The first, an index of Things. The second, a Concordance of Names. London: Printed for Nicholas Bourne, 1633. STC 23345.5.

-

Stow, John. The chronicles of England from Brute vnto this present yeare of Christ. 1580. Collected by Iohn Stow citizen of London. London, 1580.

-

Stow, John. A Summarie of the Chronicles of England. Diligently Collected, Abridged, & Continued vnto this Present Yeere of Christ, 1598. London: Imprinted by Richard Bradocke, 1598.

-

Stow, John. A suruay of London· Conteyning the originall, antiquity, increase, moderne estate, and description of that city, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow citizen of London. Since by the same author increased, with diuers rare notes of antiquity, and published in the yeare, 1603. Also an apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that citie, the greatnesse thereof. VVith an appendix, contayning in Latine Libellum de situ & nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. London: John Windet, 1603. STC 23343. U of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign Campus) copy.

-

Stow, John, The survey of London contayning the originall, increase, moderne estate, and government of that city, methodically set downe. With a memoriall of those famouser acts of charity, which for publicke and pious vses have beene bestowed by many worshipfull citizens and benefactors. As also all the ancient and moderne monuments erected in the churches, not onely of those two famous cities, London and Westminster, but (now newly added) foure miles compasse. Begunne first by the paines and industry of Iohn Stovv, in the yeere 1598. Afterwards inlarged by the care and diligence of A.M. in the yeere 1618. And now completely finished by the study and labour of A.M. H.D. and others, this present yeere 1633. Whereunto, besides many additions (as appeares by the contents) are annexed divers alphabeticall tables; especially two: the first, an index of things. The second, a concordance of names. London: Printed by Elizabeth Purslovv for Nicholas Bourne, 1633. STC 23345. U of Victoria copy.

-

Stow, John, The survey of London contayning the originall, increase, moderne estate, and government of that city, methodically set downe. With a memoriall of those famouser acts of charity, which for publicke and pious vses have beene bestowed by many worshipfull citizens and benefactors. As also all the ancient and moderne monuments erected in the churches, not onely of those two famous cities, London and Westminster, but (now newly added) foure miles compasse. Begunne first by the paines and industry of Iohn Stovv, in the yeere 1598. Afterwards inlarged by the care and diligence of A.M. in the yeere 1618. And now completely finished by the study and labour of A.M. H.D. and others, this present yeere 1633. Whereunto, besides many additions (as appeares by the contents) are annexed divers alphabeticall tables; especially two: the first, an index of things. The second, a concordance of names. London: Printed by Elizabeth Purslovv [i.e., Purslow] for Nicholas Bourne, 1633. STC 23345.

-

Stow, John. A Survey of London. Reprinted from the Text of 1603. Ed. Charles Lethbridge Kingsford. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1908. Remediated by British History Online. [Kingsford edition, courtesy of The Centre for Metropolitan History. Articles written after 2011 cite from this searchable transcription.]

-

Stow, John. A Survey of London. Reprinted from the Text of 1603. Ed. Charles Lethbridge Kingsford. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1908. See also the digital transcription of this edition at British History Online.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ &nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. 23341. Transcribed by EEBO-TCP.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ & nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. Ed. Janelle Jenstad and the MoEML Team. MoEML. Transcribed.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ &nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. Folger Shakespeare Library.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ &nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. London: John Windet for John Wolfe, 1598. STC 23341.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Coteyning the Originall, Antiquity, Increaſe, Moderne eſtate, and deſcription of that City, written in the yeare 1598, by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Since by the ſame Author increaſed with diuers rare notes of Antiquity, and publiſhed in the yeare, 1603. Alſo an Apologie (or defence) againſt the opinion of ſome men, concerning that Citie, the greatneſſe thereof. With an Appendix, contayning in Latine Libellum de ſitu & nobilitae Londini: Writen by William Fitzſtephen, in the raigne of Henry the ſecond. London: John Windet, 1603. U of Victoria copy. Print.

-

Strype, John, John Stow, Anthony Munday, and Humphrey Dyson. A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster. Vol. 2. London, 1720. Remediated by The Making of the Modern World.

-

Strype, John, John Stow. A SURVEY OF THE CITIES OF LONDON and WESTMINSTER, And the Borough of SOUTHWARK. CONTAINING The Original, Antiquity, Increase, present State and Government of those CITIES. Written at first in the Year 1698, By John Stow, Citizen and Native of London. Corrected, Improved, and very much Enlarged, in the Year 1720, By JOHN STRYPE, M.A. A NATIVE ALSO OF THE SAID CITY. The Survey and History brought down to the present Time BY CAREFUL HANDS. Illustrated with exact Maps of the City and Suburbs, and of all the Wards; and, likewise, of the Out-Parishes of London and Westminster, and the Country ten Miles round London. Together with many fair Draughts of the most Eminent Buildings. The Life of the Author, written by Mr. Strype, is prefixed; And, at the End is added, an APPENDIX Of certain Tracts, Discourses, and Remarks on the State of the City of London. 6th ed. 2 vols. London: Printed for W. Innys and J. Richardson, J. and P. Knapton, and S. Birt, R. Ware, T. and T. Longman, and seven others, 1754–1755. ESTC T150145.

-

Strype, John, John Stow. A survey of the cities of London and Westminster: containing the original, antiquity, increase, modern estate and government of those cities. Written at first in the year MDXCVIII. By John Stow, citizen and native of London. Since reprinted and augmented by A.M. H.D. and other. Now lastly, corrected, improved, and very much enlarged: and the survey and history brought down from the year 1633, (being near fourscore years since it was last printed) to the present time; by John Strype, M.A. a native also of the said city. Illustrated with exact maps of the city and suburbs, and of all the wards; and likewise of the out-parishes of London and Westminster: together with many other fair draughts of the more eminent and publick edifices and monuments. In six books. To which is prefixed, the life of the author, writ by the editor. At the end is added, an appendiz of certain tracts, discourses and remarks, concerning the state of the city of London. Together with a perambulation, or circuit-walk four or five miles round about London, to the parish churches: describing the monuments of the dead there interred: with other antiquities observable in those places. And concluding with a second appendix, as a supply and review: and a large index of the whole work. 2 vols. London : Printed for A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. ESTC T48975.

-

The Tower and St. Catherins Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections.