Ludgate

¶Location

Stow, following FitzStephen’s twelfth century description of the London Wall having

seven double-gated entranceways(FitzStephen), counts Ludgate as the

sixth principal gate(Stow 1:36). Originally there were four gates: one gate in each cardinal direction, with Ludgate granting access into the Roman city from the West. Ludgate was situated to the immediate west of St. Paul’s, at the north-eastern corner of Blackfriars. Anyone entering the city through Ludgate would have seen the large cathedral through and towering over the gate. For those leaving the city, Ludgate was the egress to Ludgate Hill, Fleet Bridge, and thence Fleet Street.

¶Name and Etymology

According to Geoffrey of Monmouth, Ludgate was built by King Lud in

66 BC, and his body is

preserved in this city next to the gate that is now named after him: Portlud in the British tongue and Ludesgata in the Saxon(Adams 83). Most etymologists believe that Ludgate likely derives its name not from King Lud but from old English

hlidgeator

hlydgeatwhich means

postern(Kent 402).

Lutgatafirst appears in a manuscript dated 1100-1135 with

Ludgatesettling from 1235 onwards (Harben 372). While we may disregard Monmouth’s history as legend, Ludgate

has no certain Roman originand archeological evidence

supports the more ancient claim(Hill 61).

¶History

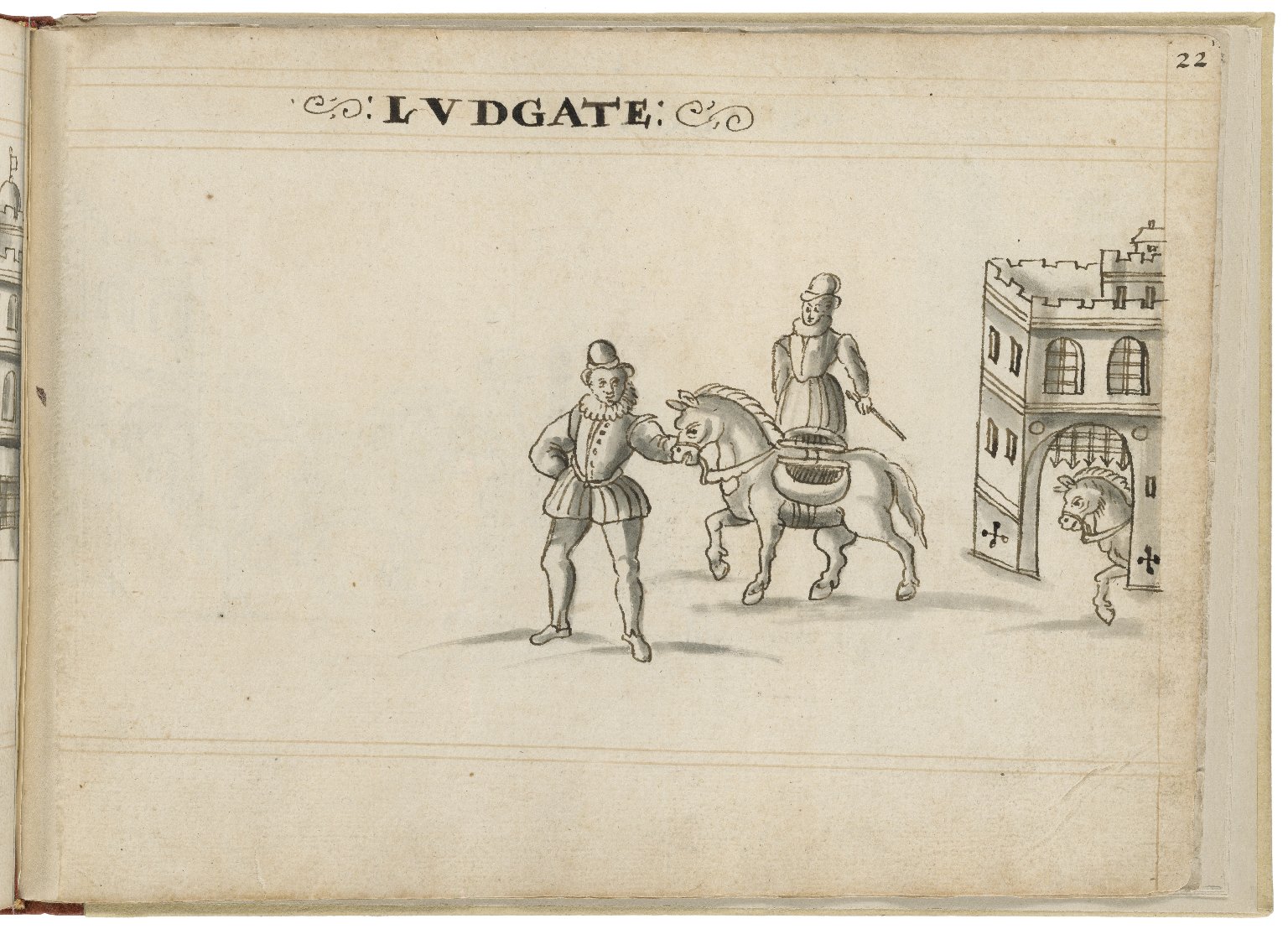

In 1378, Richard II converted Ludgate

into a prison. In 1382 it was specifically designated a free prison

by which it was ordained, that all freemen of this citie, should for debt, trespasses, accounts, & contempts, be imprisoned in Ludgate(Stow 1:39) while more serious criminals, for offences such as treason, would be sentenced to Newgate. Throughout the early modern period, Ludgate held a number of celebrity inmates, detained for their

extravagances(Heminges 8).

Ludgathians,as Jonson calls them in Every Man Out of His Humour, were

impudent creatures, turbulent creatures(Jonson 1.2.124).

Sir Thomas Mallory spent much of his later life in and out of prison—finishing Le Morte Darthur in the Abbey

Prison at St. Paul’s—and was twice committed to Ludgate: for three months in

1452, and for nine months in

1457. When Mallory returned to Ludgate

for the second time, the wardens had to pay a record penalty of £1000 should they

fail to keep him secure (Field 119).

William Heminges, son of John Heminges, was detained for a year in Ludgate sometime

in the 1630s. In his

Lines Written in Ludgate,Heminges laments his imprisonment:

(Heminges 20)No musicke here, did sothe myne earebut soundes of men in greefeWho at the gratte In woefull statedoth bellow for releife.Poor men that soe are brought to woeTo leade a Captiue LifeAnd Spend the tyme of all thier primefrom parentes Children wyfe!

The prisoners’ living conditions were notoriously unpleasant. From the chapel at Ludgate in

1659, Marmaduke Jonson complained of

the poor circumstances in a letter to the Mayor. After dividing any legacies and donations,

Jonson calculated each man’s

financial allowance:

And I hope no sober Man, or Christian, will judge, that four Pence in Bread, and six Pence in Money, can be a Competency sufficient to maintain a Man a whole Month(Strype 29). However, as a prison specifically for debtors, Ludgate usually held men of notable positions; mostly merchants and clergymen who had fallen on hard times. The legacies and donations, much lamented by Jonson, were often left by previous inmates who had been released. Famously, in 1486, Dame Agnes Forster, the widow of Stephen Forster, a successful merchant and fishmonger, Ludgathian, and later Mayor, was granted permission to make certain enlargements

for the comfort and reliefe of all the poor prisonersin memory of her late husband (Stow 1:39). Not only did she build better quality accommodations and a chapel, but she also had the roof reinforced so that the prisoners could walk upon it

for fresh ayreand, in an act of humanity, covered the cost

so that for lodging and water prisoners here nought pay, / as their keepers shal all answere at dreadful doomes day(Stow 1:40). Even more remarkably, it was while Stephen was begging during his imprisonment that this charitable Dame walked past. Paying off his debts (amounting to £20), Dame Agnes Forster took Stephen into her service, and after

falling into the Way of Merchandize,they were married:

Her Riches and his Industry brought him both great Wealth and Honour Gap in transcription. Reason: Editorial omission for reasons of length or relevance. Use only in quotations in born-digital documents. (AD)[…] Yet whilst he lived in this great Honour and Dignity, he forgat not the Place of his Captivity(Strype 26). Heywood alludes to this tale in If You Know Not Me, Part 2, repeating the verse written by Stow (Heywood 1.6.823-835).

¶Literary References

We can picture the destitute debtors thanks to several references in popular drama

and a number of surviving artifacts. A vivid description appears in

Congreve’s The Way of the World, spoken by Foilble:

He! I hope to see him lodge in Ludgate first, and angle into Blackfriars for brass farthings with an old mitten!(Congreve 3.1.121-22). The editor notes that

the prisoners would(Congreve 55).fishfor alms with a mitten let down on a line from upper windows to passers-by in the street

Since he owes a thousand pound, Fortune’s wife is described by Sir John in Massinger’s

The City Madam as traveling

To Ludgate in a Citizen(Massinger 1.3.22-8). Ludgate also features prominently in Dekker’s The Shoemaker’s Holiday where the catchphrase of the play’s protagonist, Simon Eyre, is to swear an oath by the Lord of Ludgate. Again in Dekker, with Middleton, it materialises in The Roaring Girl when it is said that

The clock at Ludgate Gap in transcription. Reason: Editorial omission for reasons of length or relevance. Use only in quotations in born-digital documents. (AD)[…] ne’er goes true(Middleton and Dekker 2.2.109).

The Humble Petition of the Poor Distressed Prisoners in Ludgate, a handbill printed in 1664,

beseeches its reader

to relieve us with your charitable benevolence, and to put into this Bearers Boxe, the same being sealed with the house seale as it is figured on this Petition(Hindley 67). One of the

Cries of Londondescribes a Ludgathian begging with an

alms-basket at his back, and a sealed money-box in his hand(Wheatley 446).

A fifteenth century manuscript titled, The Seven Names of a Prison,

concludes with the prayer:

Alle you att large pray God ffor us that be here in Ludgate(MS Harley 7526, fol. 35). The scene did not seem to change since much later; in 1711, Sir Richard Steele commented—not without social critique—in The Spectator:

Passing under Ludgate the other Day, I heard a Voice bawling for Charity, which I thought I had somewhere heard before. Coming near to the Grate, the Prisoner called me by my Name, and desired I would throw something into the Box: I was out of Countenance for him, and did as he bid me, by putting in half a Crown. (Steele)

¶Significance

In a unique description of London, Thomas

Adams assigns Ludgate an alternative numerical position:

The ſecond Gate Is Patience; which is not vnlike to Ludgate(Adams 43). Adams’ text presents Ludgate, and indeed London, as a theological alternative to the London in Stow’s Survey of London.

Peaceis here personified as the

City,its governor being God, its laws the Gospel, its buildings the church, and the river that runs through it prosperity. According to Adams, in his chapter

The Wals of Peace,patience is expressed through Ludgate

for that is a Schoole of patience; the poore ſoules there learne to ſuffer(Adams 43).

Of all the ancient gates in London, Ludgate would have been the most majestic, embellished with several sovereign

statues. King Lud himself presided over the early modern period as Henry III’s architectural

improvements had included the repair and decoration of Ludgate with a statue of King Lud and his two sons. Sometime between 1547-1553, during the reign

of Edward VI, the statues were vandalised and beheaded, most likely in an attack against Catholic

idolatry by first generation English

protestants. Queen Mary repaired the statues to their former glory

by setting new heads on old bodies(Stow 1:38). By 1586, the

same gate being sore decayed, was clean taken down Gap in transcription. Reason: Editorial omission for reasons of length or relevance. Use only in quotations in born-digital documents. (AD)[…] and the same yeare the whole gate was newly and beautifully builded(Stow 1:39). Queen Elizabeth’s reconstruction of the gate cost the citizens over £1500 but included a design for a statue of herself on the west side, with Lud demoted to the eastern wall. Holding

the sceptre in one hand, and the orb in the otherQueen Elizabeth, in all her stony splendour,

wears the side panniers and farthingale and stiff collar(Kent 519).

In his essay on Ludgate’s influence on contemporary Elizabethan drama, Harris argues that

Elizabeth’s statue above Ludgate’s entrance modelled her as the most recent incarnation of a line of monarchs that, in predating the Conquest, laid claim to a natively British vision of England and London in particular. Admittedly, Elizabeth’s statue also involved something of the logic of Christian supersession. Situated on the gate’s west side, the statue was visible to anyone entering the City through Ludgate; with the spires of St. Paul’s Cathedral looming behind the arch, Elizabeth, defender of the faith, was framed by the church, whereas the pagan Lud was visible only when one turned one’s back on St. Paul’s and prepared to leave the sanctuary of the City. ( Harris 16-17)

Elizabeth, then, was seemingly well aware of the significance of her position on the west wall

of Ludgate and

the Queen’s presence was no doubt felt strongly by the succeeding monarch, King James VI and I, who passed through Ludgate

on his delayed Royal Entry in 1604. As Harris notes of James’ passage

underneath Ludgate, it

would have had a powerful temporal as well as spatial symbolism, with the statue of Elizabeth positioned immediately behind him as he headed to his coronation at Westminster(Harris 19). Elizabeth’s statue would certainly have been a striking monument to walk beneath for either the king or a subject. Having been struck with awe at the sight of St. Paul’s during his first visit to London, a tourist narrates his experience in a ballad preserved in the British Library:

(Puiſnes 21-25)To Ludgate then I ran my race:when I was past I did backward lookther I spyed Queen Elizabeths graceHer picture guilt, for all gould I took.

Elizabeth herself, having heard the child’s oration at St. Paul’s Churchyard, then passed by a

finelie trimmedLudgate during her own passage through London in 1559 where she was

receiued with a noyse of instruments(Queen’s Majesty’s Passage D2v). Elizabeth’s entry into London on the 14 January, a day prior to her coronation, confirmed Ludgate as a traditional site of royal procession and mayoral entertainment, establishing it along the main route from the Tower and out of London towards Westminster. Jean Wilson, in her authoritative study Entertainments for Queen Elizabeth I, states that

her coronation procession was unchanged in manner and general context from previous royal entries(Wilson 5). Richard Dutton’s study of the civic pageants of the Jacobean period argues that James was also required to pass through Ludgate along the established route (Dutton 10). Furthermore, Lawrence Manley describes the

last phase of such processions which led down Ludgate Hill and Fleet Street, and out through the boundary at Temple Bar(Manley 223).

Although Temple Bar had already been designated the official boundary of London by the time of

Elizabeth’s procession, Ludgate’s situation as part of the traditional City limit created by the

London Wall would have increased its significance. In her modern edition of the Queen’s Majesty’s Passage, Germaine Warkentin demonstrates that

for townspeople living behind high walls there was an important difference between countryside and the sacred space of their city. The city walls and gates were powerful symbols of order in a world of disorder and lawlessness(Warkentin 20). One explanation why Ludgate’s entry in Richard Tottelʼs official publication of the procession is so short could be due to the fact the contemporary readers would have simply been aware of such significances imposed by Ludgate’s location. As Harris explains:

Ludgate was not just a gate but also a vital component in the symbolic topography of London. Ludgate’s signifying power as a nodal point, connecting not only the City’s inside and outside but also its past, present, and future, was deployed in civic ritual, including coronation processions and entertainments. Ludgate was the threshold between St. Paul’s and Westminster, between spiritual and earthly power. Conventionally, the new monarch would spend the night in the Tower, and then move from the east to the west of the City, pausing at the cathedral; he or she would then head west through Ludgate to Westminster for the coronation. (Harris 17)

Unlike each of the other eleven locations on Elizabeth’s procession route in which the pageantry is described in

detail, Tottel’s commemorative programme elaborates no further on the aural spectacle that occurred

at

Ludgate. It must be assumed, though, that in addition to its location, the musical welcome

at Ludgate was

also significant enough for it to have been included as one of the twelve primary

pageants. The ringing of St. Paul’s bells moments

earlier would still be reverberating in the ears of those gathered by the gate. Considering

the occasion it would be safe to assume that brass instruments would

have provided a suitably royal fanfare to mark Elizabeth’s approach. An early form of the trumpet, the trompette de guerre,

which is similar in design to the bugle since it had no valves, would have be accompanied

by cornetts and sackbutts (early trombones) as the instruments of both

war and royal pomp(Hayes 756). The musical greeting at Ludgate would have been loud enough to be heard over the gathered crowds, and able to drown out the begging shouts of the prisoners’ attempting to capitalise on the increased charity and wealth as a consequence of the procession. It is also probable that cannons may have been fired as Elizabeth approached. A dispatch by Il Schifanoya, the Venetian ambassador to the Castellan of Mantua, written just nine days after the procession, describes the procession in general where

artillery, drums, fifes, trumpets and other kinds of joyful instruments [accompanied] her Majesty and her court(qtd. in Warkentin 103).

Moreover, it was not only the gate itself that had been splendidly decorated for the

occasion; the surrounding area had certainly undergone one of the most expensive

renovations of any location along the route, and its transformation for the pageant

was so dramatic that Elizabeth herself was certainly

impressed. Preparations in transforming London for the pageant started early, and on the

7 December the Court of Aldermen

met to assign pageants and displays to various groups of guildsmen, to be set up at the traditional stations(Warkentin 37). Ludgate was allocated to Henry Nayler and John Lacy, both clothworkers; George Allen, a skinner; and Thomas Nicoll, a goldsmith (qtd. in Warkentin 118). Nicoll would surely have been tasked with gilding the statues on Ludgate, for as Puiſnes describes:

ther I spyed Queen Elizabeths grace / Her picture guilt, for all gould I took(Puiſnes 24-25). Nayler, Lacy and Allen, then, will have supplied skins and luxurious textiles to drape over the buildings. The printed text offers the following anecdote as Elizabeth passed through the gate:

From thence by the way as she went down toward Fletebridgewhere

one aboute her grace noted the cities charge, that there was no coast spared. Her grace answered that she did well consider thesame, and that it should be remembred(Queenʼs Majestyʼs Passage D3r). True to her word, Elizabeth did remember Ludgate, hence the repairs in 1586 which included her statue. Schifanoya’s letters provide an explanation as to why Elizabeth considered the streets leading towards and away from Ludgate worth remembering. He writes:

The houses on the way were all decorated; there being on both sides of the street, from Blackfriars to St. Paulʼs [which encompassed Ludgate], wooden barricades on which the merchants and artisans of every trade leant in long black gowns lined with hoods of red and black cloth, Gap in transcription. Reason: Editorial omission for reasons of length or relevance. Use only in quotations in born-digital documents. (AD)[…] with all their ensigns, banners, and standards, which were innumerable, and made very fine show. (Bergeron 13-14)

It was a remarkable scene, comparable to the modern practice of lining The Mall with

crowd barriers during royal celebrations to hold back the thousands of people waving

British flags, homemade banners, and souvenir memorabilia. Furthermore, Schifanoya’s description offers a tantalising record of the specific

conditions on the day:

Owing to the deep mud caused by the foul weather and by the multitude of people and of horses, everyone had made preparation, by placing sand and gravel in front of their houses(Bergeron 14). Again, one is reminded of the umbrellas and tents that are used today as people prepare themselves against the cold and the rain waiting, sometimes for days, to be in the best spot to catch a glimpse of the royal family. What is of most interest in Schifanoya’s notes is that the ambassador mentions an episode occurring at Ludgate that does not appear in the official pamphlet. He writes:

of Ludgate, where the prisoners of the Mayor of London are held. There were certain verses in Latin in praise of her Majesty above a little table, hanging at the front of the said gate, which was entirely painted with the arms of the City. I hear that she pardoned all those prisoners who were merely debtors. (qtd. in Warkentin 109)

It is a surprising omission by the pamphlet, since such a pardon would have caused

a considerable reaction from both those inside and outside Ludgate.

Another, even more remarkable omission is highlighted in Richard Grafton’s version of Elizabeth’s entry, published in

1563 by Tottel, who had also published the original account

in 1559. Grafton adds the following statement concerning

Elizabeth’s activity at Ludgate:

Also being humbly requested at the petition of the Mayor of London, who presented unto her Majesty in a purse one thousand marks in gold, that she would continue their good lady, she gave her answer that if need should be, she would willingly in their defence spend blood. (qtd. in Warkentin 113)

In 1603, upon Elizabeth’s death,

the Lord Mayor commanded Ludgate to be closed:

The gates at Ludgate and portcullis were shutt and downeremaining so from 3am until the Mayor received

a token besyde promise(Manningham 147) from the Lord Treasurer that James was proclaimed King.

Almost fifty years earlier and after a week of fighting his way through London, followed by a rapidly dwindling number of rebels,

Sir Thomas Wyatt reached Ludgate in early February,

1554 during a rebellion against Queen Mary’s marriage to Philip II of Spain. Finding the gate closed, his men called out that here was Wyatt

whome the Quéene had graunted to haue thier requestes(Stow 1086). Queen Mary, anticipating Wyatt’s intention to enter the City through Ludgate, ordered her soldiers to protect the gate. The recently appointed Lieutenant of the City, Lord William Howard, stood waiting and roared to Wyatt:

Auant Traytor, thou shalt not come in hére(Stow 1086).

During the First Baron’s War of 1215-1217, Ludgate

was again the site of rebellious defence and closed. Having presumably been left to

ruin it was repaired in haste. The Barons:

being in armes against the king, entered this Citie, and spoyled the Jewes houses, which being done, Gap in transcription. Reason: Editorial omission for reasons of length or relevance. Use only in quotations in born-digital documents. (AD)[…] applied all diligence to repayre the gates and wals of this Citie, with the stones of the Jewes broken houses, especially (as it seemeth) they then repayred or rather new builded Ludgate. (Stow 1:38)

Stow confirms this medieval account with a curious anecdote. A discovery made during Elizabeth’s renovation

founde couched within the wall thereof, a stone taken from one of the Jewes houses, wherein was grauen in Hebrew caracters(Stow 1:38) the name and sign of the house belonging to Rabbi Moses.

¶17th Century and Beyond

Despite being gutted, Ludgate itself

continued with but little detriment(Evelyn 15) during the Great Fire. However, while it survived the fire, Ludgate was demolished in 1760 to widen the street. Its materials were sold for the sum of £148 and it was arranged that the statue of Elizabeth, bought at a cost of £16, was to be built into the church wall of St. Dunstan in the West (Thornbury). Lud and his sons were sent to the parish bone-house but now stand under porch in the courtyard at St. Dunstanʼs, while Elizabeth still looks out over Fleet Street. This statue of Elizabeth is believed to be the oldest outdoor statue in London, since it is the only figure known to have been sculpted during her reign (

StatuesLondon Remembers). According to Kent, the memory of Ludgate was still significant in 1911 when the new monarch passed through London. A sign near Ludgate’s original location was inscribed to celebrate the coronation:

King Lud welcomes George V(Kent 402).

References

-

.

Eirenopolis.

The Map of Early Modern London, Edition 7.0, edited by , U of Victoria, 05 May 2022, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/EIRE1.htm. -

Citation

Bergeron, David M. English Civic Pageantry 1558–1642. London: Edward Arnold, 1971. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Congreve, William. The Way of the World. Ed. Brian Gibbons. London: Black, 1994. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Dutton, Richard. Jacobean Civic Pageants. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 1996. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Evelyn, John. The Diary of John Evelyn. Vol. 2. Ed. Austin Dobson. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1906. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Field, P. J. C. The Life and Times of Sir Thomas Mallory. Cambridge: Brewer, 1993. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

FitzStephen, William.A Description of London.

Florilegium Urbanum. Ed. Henry Thomas Riley. Trans. Stephen Alsford. http://users.trytel.com/~tristan/towns/florilegium/introduction/intro01.html.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Harben, Henry A. A Dictionary of London. London: Herbert Jenkins, 1918. [Available digitally from British History Online: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/dictionary-of-london.]This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Harris, Jonathan Gil.Ludgate Time: Simon Eyre’s Oath and the Temporal Economies of The Shoemaker’s Holiday.

Huntington Library Quarterly 71.1 (2008): 11–32.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Hayes, Gerald.Instruments and Instrumental Notation.

The Age of Humanism. London: Oxford UP, 1968. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Heminges, William. Elegy on Randolph’s Finger: Containing the Well-Known Lines On the Time-Poets. Ed. G. C. Moore Smith. Oxford: Blackwell, 1923. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Heywood, Thomas. The Second Part of, If you know not me, you know no bodie. VVith the building of the Royall Exchange: And the Famous Victorie of Queene Elizabeth, in the Yeare 1588. London: [Thomas Purfoot] for Nathaniell Butter, 1606. STC 13336.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Hill, William Thomas. Buried London: Mithras to the Middle. London: Phoenix House, 1955. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Hindley, Charles. A History of the Cries of London, Ancient and Modern. London, 1881. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Jonson, Ben. Every Man Out of His Humour. Ed. Helen Ostovich. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2001. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Kent, William. An Encyclopedia of London. Ed. Godfrey Thompson. Rev. ed. London: J.M. Dent, 1970. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Manley, Lawrence. Literature and Culture in Early Modern London. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Manningham, John. The Diary of John Manningham 1602–1603. Ed. John Bruce. Westminster, 1868. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Massinger, Philip.The City Madam.

The Plays and Poems of Philip Massinger. Ed. Philip Edwards and Colin Gibson. Oxford: Claredon, 1976. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Middleton, Thomas, and Thomas Dekker. The Roaring Girl. Ed. Paul A. Mulholland. Revels Plays. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1987. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Statues: St. Dunstan’s - Elizabeth I statue.

London Remembers, 20 January 2015. https://www.londonremembers.com/memorials/st-dunstans-elizabeth-i-statue.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Steele, Richard. The Spectator. No. 82, 4 June 1711. Ed. Henry Morely. London, 1891. Remediated by Project Gutenberg.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Stow, John. The chronicles of England from Brute vnto this present yeare of Christ. 1580. Collected by Iohn Stow citizen of London. London, 1580.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Stow, John. A Survey of London. Reprinted from the Text of 1603. Ed. Charles Lethbridge Kingsford. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1908. See also the digital transcription of this edition at British History Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Strype, John. A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate, and Government of those Cities. London, 1720. Reprinted as An Electronic Edition of John Strype’s A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster. Ed. Julia Merritt (Stuart London Project). Version 1.0. Sheffield: hriOnline, 2007. https://www.dhi.ac.uk/strype/index.jsp.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

The Puiſnes Walk About London. MS Harley 3910, fol. 36. British Library.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

The Seven Names of a Prison. MS Harley 7526, fol. 35. British Library.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Thornbury, Walter. Old and New London. 6 vols. London, 1878. Remediated by British History Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Warkentin, Germaine. The Queen’s Majesty’s Passage & Related Documents. Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2004. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Wheatley, Henry Benjamin. London, Past and Present: A Dictionary of its History, Associations, and Traditions. 3 vols. London: J. Murray, 1891. Reprinted by Detroit: Singing Tree P, 1968. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

.

The Will and Testament of Isabella Whitney.

The Map of Early Modern London, Edition 7.0, edited by , U of Victoria, 05 May 2022, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/WILL10.htm. -

Citation

Wilson, Jean. Entertainments for Elizabeth I. Woodbridge: Brewer, 1980. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

Cite this page

MLA citation

, and .

Ludgate.The Map of Early Modern London, Edition 7.0, edited by , U of Victoria, 05 May 2022, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/LUDG1.htm.

Chicago citation

, and .

Ludgate.The Map of Early Modern London, Edition 7.0. Ed. . Victoria: University of Victoria. Accessed May 05, 2022. mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/LUDG1.htm.

APA citation

, & 2022. Ludgate. In (Ed), The Map of Early Modern London (Edition 7.0). Victoria: University of Victoria. Retrieved from https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/editions/7.0/LUDG1.htm.

RIS file (for RefMan, RefWorks, EndNote etc.)

Provider: University of Victoria Database: The Map of Early Modern London Content: text/plain; charset="utf-8" TY - ELEC A1 - Dawson, Alex A1 - LeBere, Kate ED - Jenstad, Janelle T1 - Ludgate T2 - The Map of Early Modern London ET - 7.0 PY - 2022 DA - 2022/05/05 CY - Victoria PB - University of Victoria LA - English UR - https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/LUDG1.htm UR - https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/xml/standalone/LUDG1.xml ER -

TEI citation

<bibl type="mla"><author><name ref="#DAWS2"><surname>Dawson</surname>, <forename>Alex</forename></name></author>,

and <author><name ref="#LEBE1"><forename>Kate</forename> <surname>LeBere</surname></name></author>.

<title level="a">Ludgate</title>. <title level="m">The Map of Early Modern London</title>,

Edition <edition>7.0</edition>, edited by <editor><name ref="#JENS1"><forename>Janelle</forename>

<surname>Jenstad</surname></name></editor>, <publisher>U of Victoria</publisher>,

<date when="2022-05-05">05 May 2022</date>, <ref target="https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/LUDG1.htm">mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/LUDG1.htm</ref>.</bibl>

Personography

-

Lucas Simpson

LS

Research Assistant, 2018-2021. Lucas Simpson was a student at the University of Victoria.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Compiler

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Lucas Simpson is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Lucas Simpson is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Chris Horne

CH

Research Assistant, 2018-2020. Chris Horne was an honours student in the Department of English at the University of Victoria. His primary research interests included American modernism, affect studies, cultural studies, and digital humanities.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Copy Editor

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Chris Horne is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Chris Horne is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kate LeBere

KL

Project Manager, 2020-2021. Assistant Project Manager, 2019-2020. Research Assistant, 2018-2020. Kate LeBere completed her BA (Hons.) in History and English at the University of Victoria in 2020. She published papers in The Corvette (2018), The Albatross (2019), and PLVS VLTRA (2020) and presented at the English Undergraduate Conference (2019), Qualicum History Conference (2020), and the Digital Humanities Summer Institute’s Project Management in the Humanities Conference (2021). While her primary research focus was sixteenth and seventeenth century England, she completed her honours thesis on Soviet ballet during the Russian Cultural Revolution. During her time at MoEML, Kate made significant contributions to the 1598 and 1633 editions of Stow’s Survey of London, old-spelling anthology of mayoral shows, and old-spelling library texts. She authored the MoEML’s first Project Management Manual andquickstart

guidelines for new employees and helped standardize the Personography and Bibliography. She is currently a student at the University of British Columbia’s iSchool, working on her masters in library and information science.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Kate LeBere is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Kate LeBere is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Joey Takeda

JT

Programmer, 2018-present. Junior Programmer, 2015-2017. Research Assistant, 2014-2017. Joey Takeda was a graduate student at the University of British Columbia in the Department of English (Science and Technology research stream). He completed his BA honours in English (with a minor in Women’s Studies) at the University of Victoria in 2016. His primary research interests included diasporic and indigenous Canadian and American literature, critical theory, cultural studies, and the digital humanities.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Junior Programmer

-

Markup Editor

-

Post-Conversion Editor

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Joey Takeda is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Joey Takeda is mentioned in the following documents:

Joey Takeda authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Jenstad, Janelle and Joseph Takeda.

Making the RA Matter: Pedagogy, Interface, and Practices.

Making Things and Drawing Boundaries: Experiments in the Digital Humanities. Ed. Jentery Sayers. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2018. Print.

-

-

Tye Landels-Gruenewald

TLG

Data Manager, 2015-2016. Research Assistant, 2013-2015. Tye completed his undergraduate honours degree in English at the University of Victoria in 2015.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kim McLean-Fiander

KMF

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach, 2015–2020. Associate Project Director, 2015. Assistant Project Director, 2013-2014. MoEML Research Fellow, 2013. Kim McLean-Fiander comes to The Map of Early Modern London from the Cultures of Knowledge digital humanities project at the University of Oxford, where she was the editor of Early Modern Letters Online, an open-access union catalogue and editorial interface for correspondence from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. She is currently Co-Director of a sister project to EMLO called Women’s Early Modern Letters Online (WEMLO). In the past, she held an internship with the curator of manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library, completed a doctorate at Oxford on paratext and early modern women writers, and worked a number of years for the Bodleian Libraries and as a freelance editor. She has a passion for rare books and manuscripts as social and material artifacts, and is interested in the development of digital resources that will improve access to these materials while ensuring their ongoing preservation and conservation. An avid traveler, Kim has always loved both London and maps, and so is particularly delighted to be able to bring her early modern scholarly expertise to bear on the MoEML project.Roles played in the project

-

Associate Project Director

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Managing Editor

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Research Fellow

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Kim McLean-Fiander is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Kim McLean-Fiander is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Janelle Jenstad

JJ

Janelle Jenstad is Associate Professor of English at the University of Victoria, Director of The Map of Early Modern London, and PI of Linked Early Modern Drama Online. She has taught at Queen’s University, the Summer Academy at the Stratford Festival, the University of Windsor, and the University of Victoria. With Jennifer Roberts-Smith and Mark Kaethler, she co-edited Shakespeare’s Language in Digital Media (Routledge). She has prepared a documentary edition of John Stow’s A Survey of London (1598 text) for MoEML and is currently editing The Merchant of Venice (with Stephen Wittek) and Heywood’s 2 If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody for DRE. Her articles have appeared in Digital Humanities Quarterly, Renaissance and Reformation,Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Early Modern Literary Studies, Elizabethan Theatre, Shakespeare Bulletin: A Journal of Performance Criticism, and The Silver Society Journal. Her book chapters have appeared (or will appear) in Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society (Brill, 2004), Shakespeare, Language and the Stage, The Fifth Wall: Approaches to Shakespeare from Criticism, Performance and Theatre Studies (Arden/Thomson Learning, 2005), Approaches to Teaching Othello (Modern Language Association, 2005), Performing Maternity in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2007), New Directions in the Geohumanities: Art, Text, and History at the Edge of Place (Routledge, 2011), Early Modern Studies and the Digital Turn (Iter, 2016), Teaching Early Modern English Literature from the Archives (MLA, 2015), Placing Names: Enriching and Integrating Gazetteers (Indiana, 2016), Making Things and Drawing Boundaries (Minnesota, 2017), and Rethinking Shakespeare’s Source Study: Audiences, Authors, and Digital Technologies (Routledge, 2018).Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Author (Preface)

-

Author of Preface

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Course Instructor

-

Course Supervisor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Peer Reviewer

-

Project Director

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Janelle Jenstad is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Janelle Jenstad is mentioned in the following documents:

Janelle Jenstad authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Jenstad, Janelle and Joseph Takeda.

Making the RA Matter: Pedagogy, Interface, and Practices.

Making Things and Drawing Boundaries: Experiments in the Digital Humanities. Ed. Jentery Sayers. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2018. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Building a Gazetteer for Early Modern London, 1550-1650.

Placing Names. Ed. Merrick Lex Berman, Ruth Mostern, and Humphrey Southall. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 2016. 129-145. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

The Burse and the Merchant’s Purse: Coin, Credit, and the Nation in Heywood’s 2 If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody.

The Elizabethan Theatre XV. Ed. C.E. McGee and A.L. Magnusson. Toronto: P.D. Meany, 2002. 181–202. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Early Modern Literary Studies 8.2 (2002): 5.1–26..The City Cannot Hold You

: Social Conversion in the Goldsmith’s Shop. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

The Silver Society Journal 10 (1998): 40–43.The Gouldesmythes Storehowse

: Early Evidence for Specialisation. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Lying-in Like a Countess: The Lisle Letters, the Cecil Family, and A Chaste Maid in Cheapside.

Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 34 (2004): 373–403. doi:10.1215/10829636–34–2–373. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Public Glory, Private Gilt: The Goldsmiths’ Company and the Spectacle of Punishment.

Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society. Ed. Anne Goldgar and Robert Frost. Leiden: Brill, 2004. 191–217. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Smock Secrets: Birth and Women’s Mysteries on the Early Modern Stage.

Performing Maternity in Early Modern England. Ed. Katherine Moncrief and Kathryn McPherson. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007. 87–99. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Using Early Modern Maps in Literary Studies: Views and Caveats from London.

GeoHumanities: Art, History, Text at the Edge of Place. Ed. Michael Dear, James Ketchum, Sarah Luria, and Doug Richardson. London: Routledge, 2011. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Versioning John Stow’s A Survey of London, or, What’s New in 1618 and 1633?.

Janelle Jenstad Blog. https://janellejenstad.com/2013/03/20/versioning-john-stows-a-survey-of-london-or-whats-new-in-1618-and-1633/. -

Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. Ed. Janelle Jenstad. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/MV/.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ & nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. Ed. Janelle Jenstad and the MoEML Team. MoEML. Transcribed.

-

-

Martin D. Holmes

MDH

Programmer at the University of Victoria Humanities Computing and Media Centre (HCMC). Martin ported the MOL project from its original PHP incarnation to a pure eXist database implementation in the fall of 2011. Since then, he has been lead programmer on the project and has also been responsible for maintaining the project schemas. He was a co-applicant on MoEML’s 2012 SSHRC Insight Grant.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Conceptor

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Post-Conversion Editor

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

Contributions by this author

Martin D. Holmes is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Martin D. Holmes is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Alex Dawson

AD

Student contributor enrolled in English 124: Country, City and Court: Renaissance Literature, 1558-1618 at University of Exeter (Exon.) in Fall 2014, working under the guest editorship of Briony Frost.Roles played in the project

-

Author

Contributions by this author

Alex Dawson is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Alex Dawson is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Thomas Adams is mentioned in the following documents:

Thomas Adams authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Adams, Thomas. The devills banket described in foure sermons. London: Thomas Snodham for Ralph Mab, 1614. STC 110.5.

-

Adams, Thomas. Diseases of the soule a discourse diuine, morall, and physicall. London: George Purslowe for John Badge, 1616. STC 109.

-

Adams, Thomas. Mystical bedlam, or the world of mad-men. London: George Purslowe for Clement Knight, 1615. STC 124.

-

Adams, Thomas. The works of Thomas Adams. Ed. James Nichol. Vol. 3. Edinburgh: James Nichol, 1861–1862. Remediated by Hathi Trust.

-

Hugh Alley

Author.Hugh Alley is mentioned in the following documents:

Hugh Alley authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Alley, Hugh. Hugh Alley’s Caveat: The Markets of London in 1598: Folger MS V.a. 318. Ed. Ian Archer, Caroline Barron, and Vanessa Harding. London: London Topographical Society, 1988. Print.

-

Thomas Dekker is mentioned in the following documents:

Thomas Dekker authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Bevington, David. Introduction.

The Shoemaker’s Holiday.

By Thomas Dekker. English Renaissance Drama: A Norton Anthology. Ed. David Bevington, Lars Engle, Katharine Eisaman Maus, and Eric Rasmussen. New York: Norton, 2002. 483–487. Print. -

Dekker, Thomas, and John Webster. Vvest-vvard hoe As it hath been diuers times acted by the Children of Paules. London: [William Jaggard] for Iohn Hodgets, 1607. STC 6540.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Britannia’s Honor.

The Dramatic Works of Thomas Dekker.

Vol. 4. Ed. Fredson Bowers. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1961. Print. -

Dekker, Thomas. The Dead Tearme. Or Westminsters Complaint for long Vacations and short Termes. Written in Manner of a Dialogue betweene the two Cityes London and Westminster. 1608. The Non-Dramatic Works of Thomas Dekker. Ed. Rev. Alexander B. Grosart. 5 vols. 1885. Reprinted by New York: Russell and Russell, 1963. 1–84. Print.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The Gull’s Horn-Book: Or, Fashions to Please All Sorts of Gulls. Thomas Dekker: The Wonderful Year, The Gull’s Horn-Book, Penny-Wise, Pound-Foolish, English Villainies Discovered by Lantern and Candelight, and Selected Writings. Ed. E.D. Pendry. London: Edward Arnold, 1967. 64–109. The Stratford-upon-Avon Library 4.

-

Dekker, Thomas. If it be not good, the Diuel is in it A nevv play, as it hath bin lately acted, vvith great applause, by the Queenes Maiesties Seruants: at the Red Bull. London: Printed by Thomas Creede for John Trundle, 1612. STC 6507.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Lantern and Candlelight. 1608. Ed. Viviana Comensoli. Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2007. Publications of the Barnabe Riche Society.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Londons Tempe, or The Feild of Happines. London: Nicholas Okes, 1629. STC 6509. DEEP 736. Greg 421a. Copy: British Library; Shelfmark: C.34.g.11.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Londons Tempe, or The Feild of Happines. London: Nicholas Okes, 1629. STC 6509. DEEP 736. Greg 421a. Copy: Huntington Library; Shelfmark: Rare Books 59055.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Londons Tempe, or The Feild of Happines. London: Nicholas Okes, 1629. STC 6509. DEEP 736. Greg 421a. Copy: National Library of Scotland; Shelfmark: Bute.143.

-

Dekker, Thomas. London’s Tempe. The Dramatic Works of Thomas Dekker. Ed. Fredson Bowers. Vol. 4. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1961. Print.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The magnificent entertainment giuen to King Iames, Queene Anne his wife, and Henry Frederick the Prince, vpon the day of his Maiesties tryumphant passage (from the Tower) through his honourable citie (and chamber) of London, being the 15. of March. 1603. As well by the English as by the strangers: vvith the speeches and songes, deliuered in the seuerall pageants. London: T[homas] C[reede, Humphrey Lownes, Edward Allde and others] for Tho. Man the yonger, 1604. STC 6510

-

Dekker, Thomas. The Magnificent Entertainment: Giuen to King James, Queene Anne his wife, and Henry Frederick the Prince, ypon the day of his Majesties Triumphant Passage (from the Tower) through his Honourable Citie (and Chamber) of London being the 15. Of March. 1603. London: T. Man, 1604. Treasures in full: Renaissance Festival Books. British Library.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The owles almanacke Prognosticating many strange accidents which shall happen to this kingdome of Great Britaine this yeare, 1618. Calculated as well for the meridian mirth of London as any other part of Great Britaine. Found in an iuy-bush written in old characters, and now published in English by the painefull labours of Mr. Iocundary Merrie-braines. London: E[dward] G[riffin] for Laurence Lisle, 1618. STC 6515.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Penny-vvis[e] pound foolish or, a Bristovv diamond, set in t[wo] rings, and both crack’d Profitable for married men, pleasant for young men, a[nd a] rare example for all good women. London: A[ugustine] M[athewes] for Edward Blackmore, 1631. STC 6516.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The Second Part of the Honest Whore, with the Humors of the Patient Man, the Impatient Wife: the Honest Whore, perswaded by strong Arguments to turne Curtizan againe: her braue refuting those Arguments. London: Printed by Elizabeth All-de for Nathaniel Butter, 1630. STC 6506.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The seuen deadly sinnes of London drawne in seuen seuerall coaches, through the seuen seuerall gates of the citie bringing the plague with them. Opus septem dierum. London: E[dward] A[llde and S. Stafford] for Nathaniel Butter, 1606. STC 6522.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The Shoemaker’s Holiday. Ed. R.L. Smallwood and Stanley Wells. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1979. The Revels Plays.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The shomakers holiday. Or The gentle craft VVith the humorous life of Simon Eyre, shoomaker, and Lord Maior of London. As it was acted before the Queenes most excellent Maiestie on New-yeares day at night last, by the right honourable the Earle of Notingham, Lord high Admirall of England, his seruants. London: Valentine Sims, 1600. STC 6523.

-

Dekker, Thomas, Stephen Harrison, Ben Jonson, and Thomas Middleton. The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment of King James through the City of London, 15 March 1604, with the Arches of Triumph. Ed. R. Malcolm Smuts. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 219–279. Print.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Troia-Noua Triumphans. London: Nicholas Okes, 1612. STC 6530. DEEP 578. Greg 302a. Copy: Chapin Library; Shelfmark: 01WIL_ALMA.

-

Dekker, Thomas. TThe shoomakers holy-day. Or The gentle craft VVith the humorous life of Simon Eyre, shoomaker, and Lord Mayor of London. As it was acted before the Queenes most excellent Maiestie on New-yeares day at night last, by the right honourable the Earle of Notingham, Lord high Admirall of England, his seruants. London: G. Eld for I. Wright, 1610. STC 6524.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Westward Ho! The Dramatic Works of Thomas Dekker. Vol. 2. Ed. Fredson Bowers. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1964. Print.

-

Middleton, Thomas, and Thomas Dekker. The Roaring Girl. Ed. Paul A. Mulholland. Revels Plays. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1987. Print.

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. 1998. Remediated by Project Gutenberg.

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. Ed. Vittorio Gabrieli and Giorgio Melchiori. Revels Plays. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1990. Print.

-

Smith, Peter J.

Glossary.

The Shoemakers’ Holiday. By Thomas Dekker. London: Nick Hern, 2004. 108–110. Print.

-

Edward VI

Edward This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 6VI King of England King of Ireland

(b. 12 October 1537, d. 6 July 1553)Edward VI is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 1I Queen of England Queen of Ireland Gloriana Good Queen Bess

(b. 7 September 1533, d. 24 March 1603)Queen of England and Ireland 1558-1603.Elizabeth I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Sir Simon Eyre

Sir Simon Eyre Sheriff Mayor

(b. 1395, d. 1458)Sheriff of London 1434-1435. Mayor 1445-1446. Member of the Drapers’ Company. Husband of Alice Eyre. Father of Thomas Eyre. Son of John Eyre and Amy Eyre.Sir Simon Eyre is mentioned in the following documents:

-

William fitz-Stephen is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Dame Agnes Forster

(d. 1484)Prison reformer. Wife of Stephen Forster. Buried at St. Botolph, Billingsgate.Dame Agnes Forster is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Stephen Forster

Stephen Forster Sheriff Mayor

Sheriff of London 1444-1445. Mayor 1454-1455. Member of the Fishmongers’ Company. Possible member of the Grocers’ Company. Buried at St. Botolph, Billingsgate.Stephen Forster is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Richard Grafton is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Heminges

(b. in or before 1566, d. November 1630)Actor with the King’s Men. First editor of William Shakespeare’s First Folio. Artificer of mayoral shows.John Heminges is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Henry III

Henry This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 3III King of England

(b. 1 October 1207, d. 16 November 1272)Henry III is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thomas Heywood is mentioned in the following documents:

Thomas Heywood authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Heywood, Thomas. The Captives; or, The Lost Recovered. Ed. Alexander Corbin Judson. New Haven: Yale UP, 1921. Print.

-

Heywood, Thomas. The First and Second Parts of King Edward IV. Ed. Richard Rowland. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2005. The Revels Plays.

-

Heywood, Thomas. The foure prentises of London VVith the conquest of Ierusalem. As it hath bene diuerse times acted, at the Red Bull, by the Queenes Maiesties Seruants. London: [Nicholas Okes] for I. W[right], 1615. STC 13321.

-

Heywood, Thomas. The Second Part of, If you know not me, you know no bodie. VVith the building of the Royall Exchange: And the Famous Victorie of Queene Elizabeth, in the Yeare 1588. London: [Thomas Purfoot] for Nathaniell Butter, 1606. STC 13336.

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. 1998. Remediated by Project Gutenberg.

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. Ed. Vittorio Gabrieli and Giorgio Melchiori. Revels Plays. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1990. Print.

-

Thomas Heywood. Heywood’s Dramatic Works. 6 vols. Ed. W.J. Alexander. London: John Pearson, 1874. Print.

-

James VI and I

James This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 6VI This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 1I King of Scotland King of England King of Ireland

(b. 1566, d. 1625)James VI and I is mentioned in the following documents:

James VI and I authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

James VI and I. Letters of King James VI and I. Ed. G.P.V. Akrigg. Berkeley: U of California P, 1984. Print.

-

Rhodes, Neill, Jennifer Richards, and Joseph Marshall, eds. King James VI and I: Selected Writings. By James VI and I. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004.

-

Ben Jonson is mentioned in the following documents:

Ben Jonson authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Chapman, George, Ben Jonson, and John Marston. Eastvvard hoe. London: George Eld for William Aspley, 1605. STC 4973.

-

Chapman, George, Ben Jonson, and John Marston. Eastward Ho! Ed. R.W. Van Fossen. New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Print.

-

Dekker, Thomas, Stephen Harrison, Ben Jonson, and Thomas Middleton. The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment of King James through the City of London, 15 March 1604, with the Arches of Triumph. Ed. R. Malcolm Smuts. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 219–279. Print.

-

Gifford, William, ed. The Works of Ben Jonson. By Ben Jonson. Vol. 1. London: Nichol, 1816. Remediated by Internet Archive.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Alchemist. London: New Mermaids, 1991. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Bartholomew Fair. Ed. E.A. Horsman. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1979. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Bartholomew Fair. Ed. Suzanne Gossett, based on The Revels Plays edition ed. E.A. Horsman. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2000. Revels Student Editions. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Ben: Ionson’s execration against Vulcan. London: J. Okes for John Benson and A. Crooke, 1640. STC 14771.

-

Jonson, Ben. B. Ion: his part of King Iames his royall and magnificent entertainement through his honorable cittie of London, Thurseday the 15. of March. 1603 so much as was presented in the first and last of their triumphall arch’s. London, 1604. STC 14756.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Complete Poetry of Ben Jonson. Ed. William B. Hunter, Jr. New York: New York UP, 1963. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Complete Poetry of Ben Jonson. Ed. William B. Hunter. Stuart Edtions. New York: New YorkUP, 1963.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Devil is an Ass. Ed. Peter Happé. Manchester and New York: Manchester UP, 1996. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Epicene. Ed. Richard Dutton. Revels Plays. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2004. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Every Man Out of His Humour. Ed. Helen Ostovich. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2001. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. The First, of Blacknesse, Personated at the Court, at White-hall, on the Twelfth Night, 1605. The Characters of Two Royall Masques: The One of Blacknesse, the Other of Beautie. Personated by the Most Magnificent of Queenes Anne Queene of Great Britaine, &c. with her Honorable Ladyes, 1605 and 1608 at White-hall. London : For Thomas Thorp, and are to be Sold at the Signe of the Tigers Head in Paules Church-yard, 1608. Sig. A3r-C2r. STC 14761.

-

Jonson, Ben. Oberon, The Faery Prince. The Workes of Benjamin Jonson. Vol. 1. London: Will Stansby, 1616. Sig. 4N2r-2N6r.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Staple of Newes. The Works. Vol. 2. London: Printed by I.B. for Robert Allot, 1631. Sig. 2A1r-2J2v.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Staple of News. Ed. Anthony Parr. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben.

To Penshurst.

The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt, Carol T. Christ, Alfred David, Barbara K. Lewalski, Lawrence Lipking, George M. Logan, Deidre Shauna Lynch, Katharine Eisaman Maus, James Noggle, Jahan Ramazani, Catherine Robson, James Simpson, Jon Stallworthy, Jack Stillinger, and M. H. Abrams. 9th ed. Vol. B. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2012. 1547. -

Jonson, Ben. Underwood. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1905. Remediated by Internet Archive.

-

Jonson, Ben. The vvorkes of Beniamin Ionson. Containing these playes, viz. 1 Bartholomew Fayre. 2 The staple of newes. 3 The Divell is an asse. London, 1641. STC 14754.

-

Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary Queen of Scotland

(b. 1542, d. 1587)Queen of Scotland 1542-1567. Queen of France 1559-1560.Mary, Queen of Scots is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Mary I

Mary This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 1I Queen of England Queen of Ireland

(b. 18 February 1516, d. 17 November 1558)Mary I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Philip Massinger is mentioned in the following documents:

Philip Massinger authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Massinger, Philip.

The City Madam.

The Plays and Poems of Philip Massinger. Ed. Philip Edwards and Colin Gibson. Oxford: Claredon, 1976. Print. -

Massinger, Philip. A New Way to Pay Old Debts. London: Printed by E[lizabeth] P[urslowe] for Henry Seyle, 1633. STC 17639.

-

Thomas Middleton is mentioned in the following documents:

Thomas Middleton authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Bawcutt, N.W., ed.

Introduction.

The Changeling. By Thomas Middleton and William Rowley. London: Methuen, 1958. Print. -

Brissenden, Alan.

Introduction.

A Chaste Maid in Cheapside. By Thomas Middleton. 2nd ed. New Mermaids. London: A&C Black; New York: Norton, 2002. xi–xxxv. Print. -

Daalder, Joost, ed.

Introduction.

The Changeling. By Thomas Middleton and William Rowley. London: A&C Black, 1990. xii-xiii. Print. -

Dekker, Thomas, Stephen Harrison, Ben Jonson, and Thomas Middleton. The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment of King James through the City of London, 15 March 1604, with the Arches of Triumph. Ed. R. Malcolm Smuts. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 219–279. Print.

-

Holdsworth, R.V., ed.

Introduction.

A Fair Quarrel. By Thomas Middleton and William Rowley. London: Ernest Benn, 1974. xi-xxxix. Print. -

Middleton, Thomas, and Thomas Dekker. The Roaring Girl. Ed. Paul A. Mulholland. Revels Plays. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1987. Print.

-

Middleton, Thomas. A Chaste Maid in Cheapside. Ed. Alan Brissenden. 2nd ed. New Mermaids. London: Benn, 2002.

-

Middleton, Thomas. Civitatis Amor. Ed. David Bergeron. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 1202–8.

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Triumphs of Honour and Industry. London: Printed by Nicholas Okes, 1617. STC 17899.

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Triumphs of Integrity. Ed. David Bergeron. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 1766–1771.

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Triumphs of Love and Antiquity. London: Printed by Nicholas Okes, 1619. STC 17902.

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Triumphs of Truth. London, 1613. Ed. David M. Bergeron. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Clarendon, 2007. 968–976.

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Triumphs of Truth. London, 1613. STC 17903. [Differs from STC 17904 in that it does not contain the additional entertainment.]

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Triumphs of Truth. London, 1613. STC 17904. [Differs from STC 17903 in that it contains an additional entertainment celebrating Hugh Middleton’s New River project, known as the Entertainment at Amwell Head.]

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Works of Thomas Middleton, now First Collected with Some Account of the Author and notes by The Reverend Alexander Dyce. Ed. Alexander Dyce. London: E. Lumley, 1840. Print.

-

Taylor, Gary, and John Lavagnino, eds. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. By Thomas Middleton. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. The Oxford Middleton. Print.

-

Philip II

Philip This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 2II King of Spain King of England King of Ireland

(b. 1527, d. 1598)Philip II is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Richard II

Richard This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 2II King of England

(b. 6 January 1367, d. 1400)Richard II is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Stow

(b. between 1524 and 1525, d. 1605)Historian and author of A Survey of London. Husband of Elizabeth Stow.John Stow is mentioned in the following documents:

John Stow authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Blome, Richard.

Aldersgate Ward and St. Martins le Grand Liberty Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. M3r and sig. M4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Aldgate Ward with its Division into Parishes. Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections & Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H3r and sig. H4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Billingsgate Ward and Bridge Ward Within with it’s Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. Y2r and sig. Y3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Bishopsgate-street Ward. Taken from the Last Survey and Corrected.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. N1r and sig. N2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Bread Street Ward and Cardwainter Ward with its Division into Parishes Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. B3r and sig. B4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Broad Street Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections and Additions, & Cornhill Ward with its Divisions into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, &c.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. P2r and sig. P3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Cheape Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig.D1r and sig. D2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Coleman Street Ward and Bashishaw Ward Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. G2r and sig. G3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Cow Cross being St Sepulchers Parish Without and the Charterhouse.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H2v and sig. H3r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Creplegate Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, with Additions, and Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. I3r and sig. I4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Farrington Ward Without, with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections & Amendments.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. 2F3r and sig. 2F4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Lambeth and Christ Church Parish Southwark. Taken from ye last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. Z1r and sig. Z2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Langborne Ward with its Division into Parishes. Corrected from the Last Survey. & Candlewick Ward with its Division into Parishes. Corrected from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. U3r and sig. U4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Map of St. Gilles’s Cripple Gate. Without. With Large Additions and Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H2v and sig. H3r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Map of the Parish of St. Dunstans Stepney, als. Stebunheath Divided into Hamlets.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. F3r and sig. F4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Map of the Parish of St Mary White Chappel and a Map of the Parish of St Katherines by the Tower.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. F2r and sig. F3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of Lime Street Ward. Taken from ye Last Surveys & Corrected.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. M1r and sig. M2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of St. Andrews Holborn Parish as well Within the Liberty as Without.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. 2I1r and sig. 2I2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parishes of St. Clements Danes, St. Mary Savoy; with the Rolls Liberty and Lincolns Inn, Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig.O4v and sig. O1r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St. Anns. Taken from the last Survey, with Correction, and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. L2v and sig. L3r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St. Giles’s in the Fields Taken from the Last Servey, with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. K1v and sig. K2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Margarets Westminster Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig.H3v and sig. H4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Martins in the Fields Taken from ye Last Survey with Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. I1v and sig. I2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Pauls Covent Garden Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. L3v and sig. L4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Saviours Southwark and St Georges taken from ye last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. D1r and sig.D2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

The Parish of St. James Clerkenwell taken from ye last Survey with Corrections.