Hampton Court

¶Location

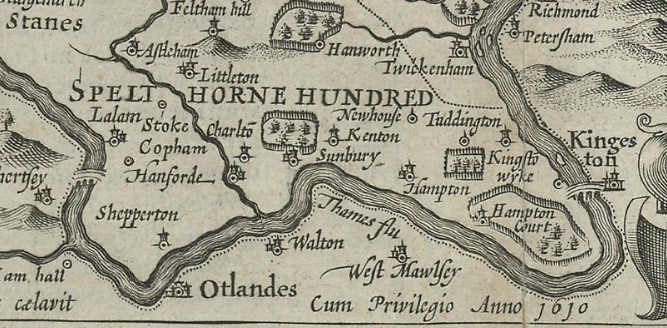

Hampton Court (c. 1236-present) was located on the north bank of the Thames, which forms its southern and western boundaries, in the parish of Hampton.

The palace was

pleasantly situatedabout 13 miles upstream of central London, according to Ernest Law’s calculation,

reckoning in a westerly direction from Charing Cross(Law 4). Hampton Court thus belonged to the hundred of Spelthorne, a subdivision of what was then known as Middlesex county, but which is currently part of Richmond upon Thames, Greater London (Law 4). In terms of its distance to the nearest towns, the palace stood

one mile southwest from the villages of Hampton and Hampton Wick,and

about one and a half miles from the town of Kingston-on-Thames(Law 4).

The Thames was commonly used as a more direct, serene highway of sorts between Hampton Court and London (

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton Court Palace, History) than the road most probably taken by the king’s coach during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, which

branche[d] from the Kingston road opposite the(Lion Gates,, to the north of the palace

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton, Introduction).

Hampton Court appears on several maps of Middlesex County including John Norden’s map of Middlesex in Speculum Britanniae, where an insert between sig. E1v and sig. E2r marks the palace roughly with a symbol

identified in the key, although the palace itself and its parks are not specifically

locatable.

John Speed’s 1611

Midle-Sex described with the Most Famous Cities of London and Westminsterindicates through a series of interlocking maps of London and Westminster their proximity to Hampton Court.

Midle-Sex described with the Most Famous Cities of London and Westminsterindicates a bridge over the Thames leading directly toward Hampton Court, perhaps suggesting more frequent visitors to the site. Image courtesy of the British Library.

Maps like Pieter Van den Keere’s 1627 engraving of Middlesex in England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland described and abridged appear, like Speed’s above, to depict the enclosure of Hampton Court’s parks from the commons. Joan Blaeu’s 1662 map of

Middle-sexiafollows suit.

John Cary’s 1790 map depicting the passage from

Hampton Court to Stainesprovides the names of prominent inns near the palace, perhaps indicating the increased need for accommodations for visitors who were not invited to stay inside. Cary also published in 1790 a map of the journey from

London to Hampton Court,similarly depicting important inns around the palace.

The Southampton Ordnance Survey map of 1868-1883 provides an aerial view of the village of Hampton, with some detail of the palace’s architectural layout.

¶Etymology and Name

Hampton Court is first referred to as

the manor of Hamntonein the Domesday Book compiled in 1086 (Law 443). In 1230 a

contentionwas recorded between Henry of St. Albans and the prior of the Hospital of St. John concerning

the house of Hampton(Close Rolls of the Reign of Henry III 451). Edward VI often referred to his birthplace as

Ampton Court(Nichols 360), but the palace is otherwise referred to as

Hampton Court,

Hampton,or the

manor of Hamptonthroughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (Law 15).

¶History

Hampton was granted to Walter of St. Valery by William the Conqueror in 1086 and remained in the possession of the St. Valery family for

considerably over a century(

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton, Manor). It passed in a relatively unbroken line of inheritance until it was taken into the hands of Henry III in 1217-1218 when, it is believed, Thomas de St. Valery forfeited his lands by joining the rebel barons in the reign of King John, continuing to rebel against Henry III’s accession even after John I’s death. Thus, c. 1218, Henry III permitted Henry of St. Albans, a merchant, citizen, and sometime sheriff of London, to retain the manor of Hampton (

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton, Manor). Henry of St. Albans remained lord of the manor until he sold it in 1236 to Terricus de Nussa, Lord Prior of the Order of the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem in England (London and Middlesex Fines: Henry III).1 Legal documents attest to the presence, however, of sisters who belonged to the order of St. John of Jerusalem as early as 1180 (Law 9). In 1292, the granddaughter of Henry of St. Albans would unsuccessfully sue the then prior of the Hospitaller order: possession by the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem was nevertheless ultimately

confirmed(Law 10;

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton, Manor).

In 1505, the manor was leased to Giles Daubeny, Chamberlain to Henry VII; he willed the lease to his wife, who survived him (Law 16). This lease is not mentioned in the formal lease executed on January 11, 1514 between Sir Thomas Docwra, Grand Prior of the Knights Hospitallers and Thomas Wolsey for the term of ninety-nine years (Law 340-343). Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon paid the first of many regular visits to Hampton Court during Wolsey’s tenure in March 1513 (

Venice: March 1514) just before he took possession of the property on Midsummer’s Day in 1514 despite the lease’s later execution in January 1514 (Law 340-343).

Wolsey chose Hampton Court for its proximity to London via the more direct route to London provided by the Thames as well as the

extraordinary salubrityof the site (Law 18). In fact, when the

Hampton Court was known for its immunity and became a site of refuge (sweating sicknessand the plague raged in London,

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton Court Palace, History).

The terms of the lease stipulated that Wolsey could build, rebuild, or alter as he chose (Law 340-343). Wolsey capitalized on this freedom, planning a palace that would allow him to appropriately

entertain his king while also claiming for himself the virtue of magnificence as the

primary characteristic of any renaissance political or religious official. When Robert Barnes confronted him for his vanity, arguing that the gold on Wolsey’s crosses could help the poor if sold off, Wolsey apparently asked Barnes:

Whether do you thinke it more necessary that I should haue al this royaltie, because I represent the kings maiesties person in all the hie courtes of this realme, to the terrour & keeping downe of all rebellions, treasons, traytors, all the wicked and corrupt members of this common wealth,or to be as simple as you would haue vs, to sell al these foresayd thinges, and to geue it to the poore, whiche shortly will pisse it agaynst the walles, and to pull awaye this maiestie of a princely dignitie, which is a terrour to all the wicked, and to follow your counsell in this behalfe. (Foxe 1217)

In his desire to build a great house to reflect his magnificence and rising station

in Henry VIII’s court, Wolsey stopped short only of the king in the opulence and scale of his building; he was

exceptionally well-positioned to do this because of his influence in the King’s Works,

a department of the royal household that

recruited the best abilities in all the trades and applied them to the architectural opportunities afforded by Crown expenditure,(Summerson 28) which extended to both Wolsey’s building projects and Henry’s (Jack).

After some time it appears that Henry, according to popular legend, became jealous of Cardinal Wolsey’s palace, and asked him why

he had built so magnificent a house for himself at Hampton Court?to which Wolsey supposedly responded astutely:

To show how noble a palace a subject may offer to his sovereign(Jerrold 11). Whether this actually happened or not, Wolsey offered Hampton Court to Henry VIII c. 1525 as a gift. Stow’s Annals note that sometime around 1525,

the saide Cardinall gave to the king the lease of the mannor of Hampton court, which he had of the lease of the lord of S. Iohns, and on which he had done great cost in building: In recompence whereof, the king licensed him to lie in his mannor of Richmond at his pleasure, and so he lay there at certain times(Stow 885).

Despite the exchange of properties between Wolsey and Henry VIII, Wolseyremained deeply involved in the affairs of Hampton Court. Documentary evidence suggests, overall, that during these years Wolsey continued to live at Hampton Court despite his gift to Henry, and may have remained responsible for overseeing expenses related to its maintenance

and Henry’s continued building (

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton, Manor). Wolsey’s fall, beginning around 1528, anticipated the legal transfer of Hampton Court to the Crown. In May 1531, the King and Sir William Weston, Prior of St. John of Jerusalem in England, concluded an agreement granting Hampton Court to Henry VIII in exchange for various monastic lands (

Henry VIII: May 1531, 16-31). In 1538, Henry created the Honour of Hampton Court by Act of Parliament (Anno tricesimo primo Henrici octavi sig. 5r).

Hampton Court has remained the property of the Crown or the State until present day, aside from

a short interval during the Commonwealth in which portions were sold to John Phelps, Edmund Blackwell, and Colonel Richard Norton (

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton, Manor). Following the battle of Naseby in 1645, Hampton Court became the property of the state. As such, the doors of the state apartments were adorned with seals of state apartments, and religious iconography in the chapel removed, including the altar rails and stained glass windows.(

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton Court Palace, History).

¶Architectural Details

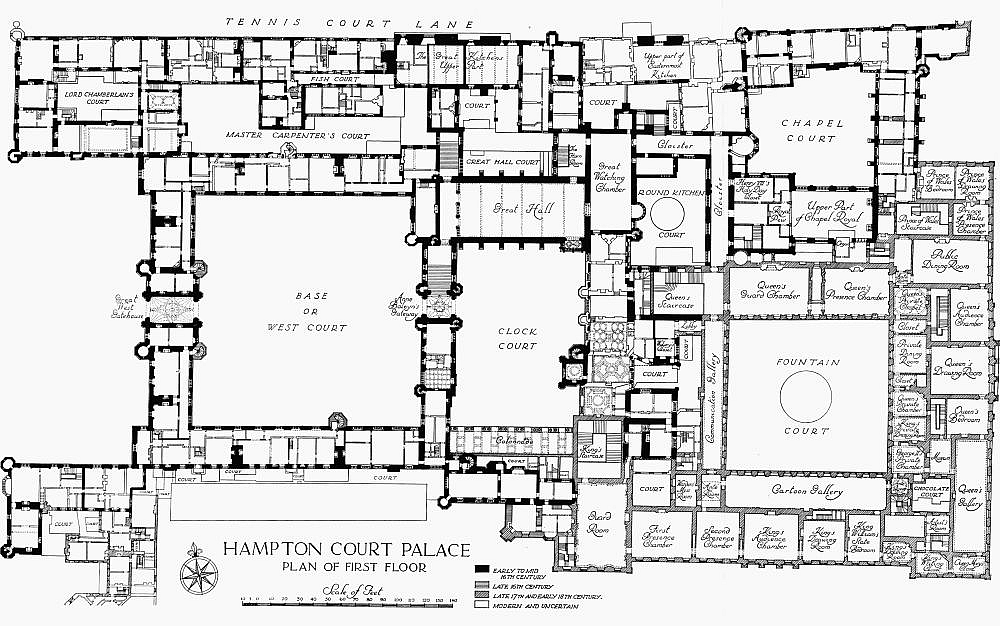

Hampton Court, in its final realization, is composed of three large quadrangles, with some detached

buildings: these are referred to as the Base Court, the Clock Court, and the Fountain

Court.

Wolsey began by converting the land into two parks partially enclosed by a brick wall and

building a moat around the house and gardens despite it being by then out of fashion.

(Law 21) Brick was also Wolsey’s primary selection for building material, followed by stone for trimmings like doorways,

windows, parapets and turrets as well as

ornamental detailsthat included

pinnacles, gargoyles, and heraldic beasts(Law 26).

Wolsey built Base Court, a good part of the Clock Court, the Chapel, the Great Hall, as

well as the gallery, and various lodgings so that by 1516 he could entertain the king at Hampton Court (Thurley 1-3). Particularly impressive are Wolsey’s

delicately moulded Gap in transcription. Reason: (LM)[…] chimney shafts, which rise in variously grouped clusters, like slender turrets, above the battlements and gables. They are all of red brick, constructed on many varieties of plan, and wrought and rubbed, with the greatest nicety, into different decorative patterns(Law 28). The layout of Base Court is characterized by its uniformity, with two stories that feature parapets and windows placed at regular intervals. The east side of Base Court is three stories tall, disrupting the elevation with turrets and rising to meet the Clock Tower, which boasts a height of eighty feet (Law 46). The gateways feature the royal arms overhead and are ornamented by terracotta roundels with portraits of Roman emperors made for Wolsey in 1521 (

Henry VIII: June 1521, 16-30).

Through the archway of the Base Court, on which Wolsey’s arms can be found, one accesses the Clock Court — named for the dial of the clock

gracing its gateway, which an inscription dated to 1540 (Law 217) — which formed the center of Wolsey’s palace. Behind the Ionic colonnade built by architect Christopher Wren in the late seventeenth-century on the south side of Clock Court stands the suite

of rooms originally occupied by Wolsey (

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton Court Palace, Architectural Description). These rooms were magnificently appointed with gold and silver tapestries, fireplaces, stained glass, a

deep-bayed oriel window,and ornate ceilings, laid out in an intricately regressive design so that visitors had to walk through eight rooms to reach Wolsey’s audience chamber (Law 55). Running along both the Base and Clock Courts stood various smaller courts, kitchens and other offices, and bedrooms for the numerous members of Wolsey’s household. The cloisters and courts to the northeast of Clock Court were likely also Wolsey’s work (

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton Court Palace, Architectural Description).

On the east side of Clock Court, Henry VIII built Anne’s Boleyn’s Gateway, characterized by a

graceful fan-groin design Gap in transcription. Reason: (LM)[…] [along with] Anne Boleyn’s own badge—the falcon—and her initial, A, entwined with an H in a true-lover’s knot(Law 164). Henry’s Great Hall was designed in a Gothic style revised Wolsey’s original design. Henry’s Great Hall stood over a range of cellars, and comprised seven bays, a dais, and a floor-to-ceiling bay window with forty-eight lights that illumined the King’s table. The Great Hall’s most remarkable feature, however, was a vaulted stone ceiling decorated with Italianate pendants nearly 5 feet in length carved for Henry (Thurley 10-11). Behind a screen at the lower end of the Great Hall are the main entrances into the hall, through which guests could enter from the courts and household staff could enter from the kitchens and offices.

The Minstrel Galleryabove this screen was built for minstrels to play

during banquets, interludes, masquerades, balls, and other festivities(Law 170).

On the east side of the Clock Court were five sequential rooms that comprised the

King’s Presence Chamber and Henry’s private rooms. Henry added to the existing chapel built during Wolsey’s time an organ chamber and a vaulted wooden roof. The roof is ornamented with three

rows of gilded pendants, each encircled by four angels playing pipes, singing from

scrolls, or holding sceptres. The arms and initials of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour appear on the west door of the chapel and are supported by angels, perhaps covering

both Anne Boleyn’s and Wolsey’s arms (Law 178-186).

Fountain Court is largely the work of Sir Christopher Wren in the late seventeenth century (Downes). However, Henry constructed the queen’s lodgings, originally built for Anne Boleyn but never occupied by her, and located on the east side of what is now Fountain Court.

The current Fountain Court is three stories, and contains a cloister and private apartments

on the ground floor; primary apartments on the first floor accompanied by a mezzanine

for added height; and suites of rooms on the third floor. The King’s Great Staircase

was added during the reign of William III and leads directly to the King’s Guard Chamber overlooking the privy garden. The

staircase opens up into a series of rooms: the Presence Chamber, the second Presence

Chamber, the Audience Chamber, the King’s Drawing-room, and his State Bedroom. The

Queen’s Guard Chamber and Presence Chamber occupy the north side of Fountain Court,

and can be entered through the Queen’s Great Staircase. These rooms open toward the

Public Dining-room which grants access to the Queen’s Apartments: Audience Chamber,

Drawing-room, and Bedroom. Behind these public rooms stand the private apartments

of William III and Mary, interlocked as well. (

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton Court Palace, Architectural Description).

¶Artistic and Cultural Significance

During the 16th and 17th centuries, Hampton Court was both the site and the subject of various artistic projects ranging from literary

and dramatic endeavors to material objects d’art and musical performances. For example,

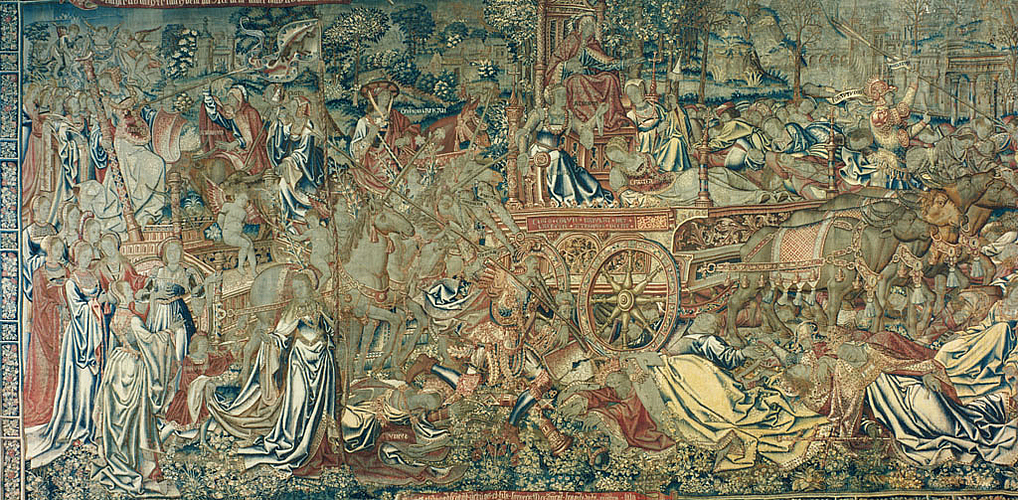

Wolsey’s design of the palace featured a series of six tapestries, in the Flemish style,

which allegorically illustrated Petrarch’s Triumphs.

Each tapestry figured two distinct aspects of the allegorized triumph pictured; over

each tapestry were written on a scroll

quaint old French verses or legends, in black letter, indicating the moral of the allegory beneath. In each piece a female, emblematic of the influence whose triumph is celebrated, is shown enthroned on a gorgeously magnificent car drawn by elephants, or unicorns, or bulls, richly caparisoned and decorated; while around them throng a host of attendants and historical personages, typical of the triumph portrayed (Law 64-65)

Wolsey used the opulence of his palace as a backdrop for performances of all sorts, including

masquerades. He once entertained Henry VIII with a masquerade at Hampton Court in which thirty-six disguised masquers were clothed in green satin, gold cloth and

laces, and hoods; the maskers one by one removed their vizors while they danced, revealing

themselves to the king before moving onto a banquet of

countless dishes of confections and other delicaciesand entertainment in the form of dice and dancing (

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton Court Palace, History). Wolsey’s masques were sometimes private entertainments for the king and select courtiers, but often included Henry’s entire court and even served to entertain ambassadors and envoys from other nations. While Henry immensely enjoyed such performances, his joy eventually gave way to jealousy.

John Skelton’s poem

Why come ye not to court?written and circulated around 1522 or 1523, is thought to have set the stage for Henry’s supposed jealousy of Wolsey’s palace. Skelton satirizes Wolsey’s far-reaching ambition, suggesting that perhaps Wolsey sought to outstrip Henry in political grandeur and preeminence:

Punning on the word court, Skelton’s speaker intentionally appears to confuse the king’s court with Wolsey’s at Hampton Court, suggesting that this confusion is the fantasy Wolsey might wish to make a reality. Skelton’s poetic speaker invites readers to ponder theWhy come ye not to court?—To which court?To the king’s court,Or to Hampton Court?Nay, to the king’s court:The king’s courtShould have the excellence;But Hampton CourtHath the preeminence,And York’s Place,With my lord’s grace,To whose magnificenceIs all the confluence,Suits and supplications,Embassades of all nations(Skelton 396-412)

magnificencethat draws to Wolsey’s court, rather than to the King’s, a

confluence, / Suits and supplications,and the

Embassades of all nations,demonstrating the threat Wolsey’s possession of Hampton Court posed to Henry VIII’s political authority.

Anne Boleyn and Henry VIII, like Wolsey, presided at many masques, banquets, and Christmas celebrations. She and Henry made Hampton Court a popular location for gambling and sports (including tennis and bowling), Anne Boleyn even learning to shoot a target (Law 131). Henry built a large Tilt Yard with five towers for spectators which were rediscovered in

2015 on the north side of the palace, where Henry excelled in numerous jousts (Historic Royal Palaces). The couple also shared a love of music, employing various court musicians and minstrels

at Hampton Court. Anne Boleyn also promoted needlework among her ladies at Hampton Court, and some of her work remained there long after her death (Harris 230).

As evidence of his interest in portraiture the painting called

The Family of Henry VIII,painted around 1545, sits in the Haunted Gallery of Hampton Court, depicting King Henry seated beneath a canopy of state surrounded by Jane Seymour, Edward VI, Princess Mary (later Mary I), Catherine of Aragon, and Princess Elizabeth (later Elizabeth I). Known to have been housed at Hampton Court by 1598 are portraits of other notable persons such as Edward VI, Mary Queen of Scots, and Henry VIII alongside important events like the Battle of Pavia (Law 335).

While Elizabeth did not use Hampton Court often as a residence or hold court there, the palace was well known for its festivities,

especially those held during Christmas. During her tenure, visitors to Hampton Court enjoyed gorgeous pageantry, banquets, balls, masquerades, masques, revels, plays,

sports, and pastimes (Streitberger 260). Christmas of 1572 saw Elizabeth at Hampton Court celebrating with, for example, nightly masques and plays in the Great Hall; banquets

perhaps in the Great Watching Chamber; masquerades, games, or minstrels and dancing

later on in the evening; hunting, tilting, and tennis during the day (Streitberger 101-102). Elizabeth again spent Christmas with great cheer at Hampton Court in 1576; six plays were presented at Hampton Court that year, including The historie of Error showen at Hampton Court on New Year’s Day at night, which conjecture has it may have been a source for Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors (Cunningham 102).

During the Christmas celebrations of 1593, Thomas Churchyard presented to Elizabeth at Hampton Court a poem titled

A Pleasant Conceite, penned in verse, collourably sette out, and humbly presented, on New-Yeere’s Day to the Queene’s Majestie at Hampton Courte; anno Domini 1593-4(Nichols 720).

The

water poetJohn Taylor’s

The Praise of the Needle,published in his book called The Needles Excellency in 1631 mentions some of Mary I’s needlework housed at Hampton Court:

In Windsor Castle and in Hampton Court,In that most pompous room called Paraddise,Whoever pleases thither to resort,May see some works of her’s of wondrous price.Her greatness held it no disreputationTo hold the needle in her royal hand;Which was a good example to our nation,To banish idleness throughout the land(Law 336)

James I and Anne of Denmark were well-known for putting on all manner of plays, masques, and frivolities. In

January of 1603/4, the Great Hall of Hampton Court staged Samuel Daniel’s The Vision of the Twelve Goddesses, a masque composed as part of the Christmas festivities organized by James I and his wife (Wiggins 53-64). Hampton Court was also the locale of theological discussions and debates: the Hampton Court Conference in 1603/1604, and the 1606 sermons given by English divines invited by James I to preach before several ministers from the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.2

In 1636, William Cartwright composed and put on The Royal Slave for Charles I and Henrietta Maria. Other plays performed at Hampton Court during the plague that occurred between November 1636 and January 1636/7 included: The Coxcombe, The Loyal Subject, Love’s Pilgrimage, Love and Honor, The Elder Brother, Fletcher’s A Kinge and No Kinge, and the two most notable, Shakespeare’s Hamlet and The Moore of Venice; performances that year also included Beaumont and Fletcher’s The Maid’s Tragedy. (Cunningham xxiv-xxv).

Hampton Court is the setting for yet another satire on contemporary society. Alexander Pope’s mock-heroic narrative poem,

The Rape of the Lock,takes as its setting Hampton Court in Canto III.

Hampton Court, still majestic and proud by the beginning of the eighteenth century, provides the ideal backdrop for satirizing the trivial family feuds and tragedies of high society in epic form.Close by those meads forever crown’d with flowersWhere Thames with pride surveys his rising towersThere stands a structure of majestic frame,Which from the neighb’ring Hampton takes its name(Pope 3.1-4)

¶Political Significance

It has been adeptly noted that

the history of Hampton Court Palace may almost be said to be the history of England(

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton Court Palace, History). In particular, this comment refers to the palace’s

intimate connexion with the private lives of kings and statesmendue to the fact that

there were few questions of political importance that were not discussed by the Privy Council, which met frequently within its walls, and innumerable letters and documents which have made history are dated from it(

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton Court Palace, History).

During Wolsey’s tenure, Hampton Court was a center of political thought, discussion, and correspondence especially with

regard to foreign affairs. Hampton Court was the seat from which Wolsey (even after he had gifted the palace to Henry VIII received and responded to letters of international political import, entertained

ambassadors—for example, envoys from the Netherlands, the French ambassador Du Bellay, and representatives of the Holy Roman Emperor—and held meetings of the Privy Council integral to positioning England as a leading power in the wake of the English Reformation in particular (Law 113-114).3 Hampton Court was the site of negotiations for a peace treaty with France in August 1527, followed by a further alliance accompanied by Henry VIII’s promise of his daughter Mary I to Francis I the following March (

Henry VIII: May 1527, 6-10,No. 3105).4

After the rebellions of 1549, fuelled by religious and economic discontent, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset faced a massive threat to his ill-gotten and almost monarchical

reign as Edward VI’s Lord Protector. Members of the Privy Council left for London in order

to demand his removal as lord protector, and in this they eventually procured the support of the mayor and aldermen of London(Beer,

Seymour, Edward, duke of Somerset). The Privy Council had lost faith in Somerset’s ability to govern, questioning his enclosures commission and condemning his reluctance to use force and assume military responsibility during the rebellion. In fear for his demise, Somerset commanded all subjects to arm themselves and defend the king at Hampton Court on October 5-6, 1549. When this did not go exactly as planned, Somerset hurried Edward off to Windsor on the pretext that Edward’s life was in danger. Somerset was eventually arrested on October 11th; he was formally charged on October 13th and later lost his Protectorship and other titles (Literary Remains of Edward VI 233-245). Later, in early October 1551, charges were made secretly against Somerset by Thomas Palmer. On October 11, 1551 Somerset attended ceremonies at Hampton Court celebrating promotions in the peerage for the Earl of Warwick,5 who was created Duke of Northumberland, and the Marquis of Dorset,6 who became Duke of Suffolk. Two days later, Edward was informed of the secret charges and left Hampton Court. Somerset was accused of treason and felony, for which he was executed in January 1552. (Literary Remains of Edward VI 350-51, 390).

On October 30 1568, an important council was held at Hampton Court to determine England’s course of action in the wake of Mary, Queen of Scots’ indictment for her husband’s murder by the Scottish lords. In December, Elizabeth called the earls of Northumberland, Westmorland, Shrewsbury, Worcester, Huntington

and Warwick to be her council at Hampton Court and help determine Mary’s fate.(Goodall 179-180;254-255).

In January 1604, James I held in the Privy Chamber what is now known as the Hampton Court Conference, a response

to the Millenary Petition presented the previous April by Puritan ministers who objected to certain ceremonial practices in the church.

The conference was attended by leaders of the established church and Presbyterians,

and was aimed at addressing questions of religious conformity. However, debates between

James and Puritan representatives became tense, and it was at this meeting that James is believed to have said,

No bishop, No King,thus rejecting many of the Puritan objections to his intended theological policies (Wormald). Nevertheless, the Hampton Court Conference was a political landmark because it led to realizing his 1601 proposal of a new translation of the Bible, which he had himself begun by translating the Psalms. The Hampton Court Conference would eventually be responsible for the publication, in 1611 of the Authorized Version, a testament to the

shared interestbetween the king and the Puritans (Wormald).

Like the monarchs before him, Charles I used Hampton Court to conduct international politics, and hosted ambassadors from Denmark, France, and

Transylvania in the year 1625 alone (Lyson 7-8). Charles was at Hampton Court in December 1641, when Parliament presented to him the Grand Remonstrance. A few months later, Charles fled once again to Hampton Court, effectively surrendering London after attempting to arrest key members of Parliament (Heath 27-36). Charles returned to Hampton Court as prisoner for several months in 1647/8 (Evelyn 242). He was treated with appropriate dignity and stateliness, dining in the Presence

Chamber, retaining his servants and chaplains, receiving visits from his two younger

children and even enjoying relatively friendly conferences with Cromwell; he was, however, kept under a guard of Parliamentary soldiers whom he managed to

escape in November 1647 (

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton Court Palace, History).

¶Important Royal Events and Ceremonies

In July 1533, Anne Boleyn was honoured with a series of celebrations following her coronation that previous

June (

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton Court Palace, History).

In September 1537 Jane Seymour retired to Hampton Court in anticipation of the birth of Edward VI. The king was present when Edward was born on Friday October 12, the vigil of St. Edward’s Day, 1537, at two o’clock in the morning (

12 Oct 1537: Seymour, Jane, Queen consort of Henry VIII to Privy Council to Henry VIII, King of England). Edward’s christening, held in the chapel at Hampton Court on October 15, was preceded by a lavish procession and included an elaborate ceremony. Jane Seymour died of post-childbirth complications at Hampton Court on October 24, 1537.7 She was the subject of intense mourning and extravagant ritual in her presence chamber, and was then interred in the chapel at Hampton until her funeral at Windsor Castle (Beer,

Jane [Jane Seymour]). Edward remained at Hampton Court and was appointed a regular household at Hampton in March 1538, though it did not remain his primary residence.

Anne of Cleves spent several days alone at Hampton Court awaiting the decree of divorce from Henry in July 1540 (Law 216). On August 8, 1540, Catherine Howard appeared openly as queen at Hampton Court, and sat next to the king in the royal closet in the chapel (Wriothesley 121-122).8 She afterwards dined in public at one of Henry’s characteristic Hampton Court banquets, and the Princess Elizabeth appeared with her, apparently for the first time together (

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton Court Palace, History). While hearing mass at his chapel in Hampton Court, Henry VIII was informed by Archbishop Cranmer of the allegations against Catherine’s chastity that would eventually lead to her execution; after Henry’s hasty departure from Hampton Court, Catherine Howard was informed of the charges against her and signed a confession (Proceedings of the Privy Council, Vol VII 352-355; Law 226).

On July 12 1543 Henry VIII married his last wife, Catherine Parr

in the queen’s closet at Hampton Court with eighteen people in attendance(James). On the Sunday before Christmas Eve of the same year the queen’s brother, Lord Parr,9 was created Earl of Essex, and Sir William Parr, her uncle, Lord Parr of Horton (Hall 859).

In July 1551, Edward VI was initiated into the Order of St. Michael by the French envoys Marshal St. Andre and Monsieur de Gie in a ceremony in the chapel at Hampton Court (Literary Remains of Edward VI 331-332).

Marie de Guise visited Hampton Court in the autumn of 1551, where she was entertained with a banquet, music, and dancing in the Great Hall (Law 258).

In April 1555 Mary I came to Hampton Court to await the birth of her child, met with sumptuous and thorough preparations for

what would turn out to be a false pregnancy (Lemon 67). During this time, Mary summoned Elizabeth I, who had been imprisoned at Woodstock for her suspected role in the Wyatt rebellion, to Hampton Court; after Elizabeth had been kept there as a prisoner for about three weeks, Mary called her to a private meeting in which she freed her and treated her thereafter

as her heir. Elizabeth remained at Hampton as part of Mary’s court, attending mass in the chapel often, and was eventually granted permission

to retire from court in August, when Mary left Hampton Court (Law 278-279).

In 1619, Anne of Denmark became seriously ill with consumption and moved to Hampton Court, where she died on March 2 (

21 Jan 1620: Herbert, Gerard to Ward, Samuel).

Mary Cromwell, daughter of Oliver Cromwell, was married to Lord Falconbridge10 in the chapel at Hampton Court on November 17, 1657. Another Cromwell daughter, Elizabeth Claypole, died at Hampton Court after a short illness in 1658 (

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton Court Palace, History).

¶Recent Discoveries

In recent years, several important archaeological discoveries have been made at Hampton Court that provide insight into the social, cultural, and political significance of the

palace.

In 2015, apartments believed to have belonged to Anne Boleyn and Jane Seymour were discovered beneath the floorboards of the Gregorian apartments used by the Royal

School of Needlework (Kennedy). Because of these findings, it is now possible to further understand the building

process during Henry VIII’s tenure at Hampton Court.

As part of a project to investigate and recreate one of Henry VIII’s famous Tudor courtyards, a team lead by Oxford Archaeology fortuitously discovered

two sets of buildings built during the mid-fourteenth and late-fifteenth centuries,

respectively. Documentary evidence suggests that these might be buildings dating to

the time of the Knights Hospitallers. This is corroborated by an account of Edward III’s visit to the manor during which a fire destroyed part of the building and Edward oversaw its reconstruction (BAJR).

Notes

- This exchange is alternatively glossed in A Topographical Dictionary of England:

The manor subsequently became the property of Sir Robert de Grey, whose widow, in 1211, left it to the Knights Hospitallers, and they at one period had an establishment here for the sisters of that order

(Lewis 307). According to William Page,Tanner and Dugdale have both made the mistake of supposing that Lady Joan de Grey was herself the donor of the manor of Hampton to the Knights Hospitallers. What really happened seems to have been that Joan de Grey inherited the manor of Shobington in Buckinghamshire from her father Thomas de Valognes, it having been part of the dowry of her mother Joan de Valognes. This manor in 1298-1299 Joan de Grey granted in mortmain to the Knights Hospitallers, but with their permission retained her life interest in it, and at the same time had granted to her by them a life interest in the manors of Hampton in Middlesex and of Raynham in Essex, possibly in return for or in acknowledgement of the actual gift which she had made to them of Shobington

(Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton, Manor

). However, most accounts have dismissed this account in favor of the one provided above. (LM)↑ - See, for example, A Sermon Preached Before the Kings Maiestie at Hampton Court, Concerning the Right and Power of Calling Assemblies on Sunday the 28 of September 1606, by the Bishop of Chichester and A Sermon Preached at Hampton Court Before the Kings Maiestie on Tuesday the 23 of September 1606. (LM)↑

- For a description of the Wolsey’s 1527 reception of the French ambassador, see Jerrold 12-13. (LM)↑

- After marriage negotiations had been concluded, the French ambassadors were

admitted to the queen’s

The ambassadors later moved to the Cardinal’s quarters to discuss the treaty, which was ratified and signed at a later date by Henry at Greenwich but still known as thechamber

, and talked with the king on indifferent matters, discussing Luther and his heresy, and the book that Henry had lately written; the king showing himself, as Dodieu says,very learned.

Treaty of Hampton Court

in honour of the place in which the negotiations were held (Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton Court Palace, History

). (LM)↑ - I.e., Sir John Dudley. (MR)↑

- I.e., Sir Henry Grey. (MR)↑

- Stow’s Annals dates Seymour’s death to October 14, 1537. However, this has largely been disproven, as evidenced by Henry’s letter to Francis I announcing Seymour’s death. See letter 972 in

Henry VIII: October 1537, 21-25.

(LM)↑ - While contemporary accounts suggest that Henry married Catherine Howard in a private ceremony on July 28 1540 at Oatlands Palace in Surrey, Wriothesley contends that they were married at Hampton Court on August 8th 1540. See Warnicke. (LM)↑

- I.e., Sir William Parr. (MR)↑

- I.e., Thomas Belasyse. (MR)↑

References

-

Citation

Anno tricesimo primo Henrici octavi Henry the VIII. by the grace of God kyngeof England and of France, defender of the fayth, Lorde of Irelande, and in earth supremehed immediatly vnder Christ of the churche of Englande, to the honour of almyghty God, conseruation of the true doctrine of Christes religion, and for the concorde quiet and vvelth of this his realme and subiectes of the same helde his moste hyghe court of Parliament begonne at VVestm[inster] the. xxviii. daye of Aprill, and there continued tyll the. xxviii. daye of Iune, the. xxxi. yere of his most noble and victorious reigne, vvherin in vvereestablysshed these actes folovvinge. London: Thomas Berthelet, 1539. STC 9397.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Beer, Barret L.Seymour, Edward, duke of Somerset (c.1500–1552).

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H.C.G. Matthew, Brian Harrison, Lawrence Goldman, and David Cannadine. Oxford UP. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/25159.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Beer, Barret L.Jane [Jane Seymour] (1508/9–1537).

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H.C.G. Matthew, Brian Harrison, Lawrence Goldman, and David Cannadine. Oxford UP. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/14647.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Cunningham, Peter. Extracts from the Accounts of the Revels at Court, in the Reigns of Queen Elizabeth and King James I, from the Original Office Books of the Masters and Yeomen.London: The Shakespeare Society, 1842. Remediated by Internet Archive.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Downes, Kerry.Wren, Sir Christopher (1632–1723).

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H.C.G. Matthew, Brian Harrison, Lawrence Goldman, and David Cannadine. Oxford UP. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/30019.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Evelyn, John. The Diary of John Evelyn. Vol. 1. Ed. William Bray. London: Walter Dunne, 1901. Remediated by Internet Archive.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Foxe, John. The Unabridged Acts and Monuments Online. Book 8. 1578 edition. The Digital Humanities Institute. Sheffield, 2011. https://www.dhi.ac.uk/foxe/index.php.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Goodall, Walter.No. LXVIII: Proceedings in council at Hampton-court, 30 Octobris 1568

in An Examination of the Letters, Said to be Written by Mary Queen of Scots, to James Earl of Bothwell: Also, An Inquiry into the Murder of King Henry. Vol II. Edingburgh: T. and W. Ruddimans, 1754 Remediated by Google Books.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Hall, Edward. Hall’s Chronicle; Containing the History of England, During the Reign of Henry the Fourth, and the Succeeding Monarchs, to the End of the Reign of Henry the Eighth, in which are Particularly Described the Manners and Customs of Those Periods. Ed. Ellis, Henry. London: Printed for J. Johnson et al., 1809. Remediated by Internet ArchiveThis item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Harris, Barbara J. English Aristocratic Women 1450-1550: Marriage and Family, Property and Careers. (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2002).This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Heath, James. A Chronicle of the Late Intestine War in the Three Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland. London: Printed by J.C. for Thomas Basset, 1676. Remediated by Google Books.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Henry VIII: June 1521, 16-30

in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 3, 1519-1523. Ed. JS Brewer. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1867. 541-553. Remediated by British History Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Henry VIII: May 1527, 6-10

in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 4, 1519-1523. Ed. JS Brewer. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1875. 541-553. Remediated by British History Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Henry VIII: May 1531, 16-31

in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 5, 1531-1532. Ed. James Gairdner. Vol. 10. London, 1880. 111-130. Remediated by British History Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Henry VIII: October 1537, 21-25

in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 12 Part 2, June-December 1537. Ed. James Gairdner. London, 1891. 3335-345. Remediated by British History Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Herbert, Gerrard.21 Jan 1620: Herbert, Gerard to Ward, Samuel.

Oxford: Bodleian Library, 1620. Remediated by Early Modern Letters Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Jack, Sybil M.Wolsey, Thomas (1470/71–1530), royal minister, archbishop of York, and cardinal.

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H.C.G. Matthew, Brian Harrison, Lawrence Goldman, and David Cannadine. Oxford UP. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29854.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

James, Susan E.Katherine [Katherine Parr] (1512–1548).

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H.C.G. Matthew, Brian Harrison, Lawrence Goldman, and David Cannadine. Oxford UP. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/4893.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Jerrold, Walter. Hampton Court.London: Little, Blackie and Son limited, 1912. Remediated by Internet Archive.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Kennedy, Maev.Hampton Court’s Lost Apartment Foundations Uncovered.

The Guardian. Guardian News & Media, 12 February 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2015/feb/12/hampton-courts-lost-apartment-foundations-uncovered.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Law, Ernest. The History of Hampton Court Palace. Vol 1, 2nd ed. London: G. Bell and Sons, 1903. Remediated by Internet Archive.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Lemon, Robert, eds. Queen Mary - Volume 5: January 1555.Calendar of State Papers Domestic: Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth, 1547-80.

London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1856. Remediated by British History Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Lewis, Samuel, ed.Hampstead - Hampton-Wick.

A Topographical Dictionary of England. Vol 2. London: S. Lewis and Co., 1831. Remediated by Google Books.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

London and Middlesex Fines: Henry III.

A Calendar To the Feet of Fines For London and Middlesex: Volume 1, Richard I - Richard III. Eds. William John Hardy and William Page. London: 1892. 12-49. Remediated by British History Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Lysons, Daniel. Account of Hampton Court Palace (From Lyson’s Middlesex parishes). London: printed by A. Strahan, 1800. Remediated by Eighteenth Century Collections Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

BAJR (British Archaeology and Jobs Resource).New Evidence of Hampton Court’s Medieval Past.

British Archaeology News Resource. December 14, 2015. http://www.bajrfed.co.uk/bajrpress/new-evidence-of-hampton-court-palaces-medieval-past/.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Nicholas, Harris, ed. Proceedings and Ordinances of the Privy Council of England. Vol. 3. London: G. Eyre and A. Spottiswoode, 1837. Remediated by Hathi Trust.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Nichols, John. The Progresses and Public Processions of Queen Elizabeth I: A New Edition of the Early Modern Sources. Ed. Elizabeth Goldring, Faith Eales, Elizabeth Clarke, Jayne Elizabeth Archer, Gabriel Heaton, and Sarah Knight. Vol. 3. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2014. Remediated by Google Books.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Nichols, John Gough, ed.Journal.

Literary Remains of King Edward the Sixth. Vol. 2. London: J.B. Nichols & Son, 1857. Remediated by Internet Archive.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Norden, John, John Speed, and Jodocus Honidus.Middle-sex Described with the Most Famous Cities of London and Westminster.

The Theatre of the Empire of Greant Britaine. By John Speed. London: George Humble, 1611. Insert after sig. H2r. [See more information about this map.]This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Pope, Alexander.The Rape of the Lock.

Ed. Jack Lynch.http://jacklynch.net/Texts/rapelock.html.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Seymour, Jane.12 Oct 1537: Seymour, Jane, Queen consort of Henry VIII, 1508-1537 (Hampton Court Palace, Richmond upon Thames, London, England) to Privy Council to Henry VIII, King of England, 1509-1547.

Oxford: Bodleian Library, 1537. Remediated by Early Modern Letters Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Skelton, John.Here after Foloweth a Litle Boke Whyche Hathe to Name, Whye Come Ye Not to Courte. Compyled by Mayster Skelton Poete Laureate.

London: J. Day for Abraham Veale, 1558. STC 22617a.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton, History.

A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 2, General; Ashford, East Bedfont With Hatton, Feltham, Hampton With Hampton Wick, Hanworth, Laleham, Littleton. Ed. William Page. London: Victoria County History, 1911. 327-371. Remediated by British History Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton, Introduction.

A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 2, General; Ashford, East Bedfont With Hatton, Feltham, Hampton With Hampton Wick, Hanworth, Laleham, Littleton. Ed. William Page. London: Victoria County History, 1911. 319-324. Remediated by British History Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton, Manor.

A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 2, General; Ashford, East Bedfont With Hatton, Feltham, Hampton With Hampton Wick, Hanworth, Laleham, Littleton. Ed. William Page. London: Victoria County History, 1911. 324-327. Remediated by British History Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Spelthorne Hundred: Hampton Court Palace, Architectural Description.

A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 2, General; Ashford, East Bedfont With Hatton, Feltham, Hampton With Hampton Wick, Hanworth, Laleham, Littleton. Ed. William Page. London: Victoria County History, 1911. 371-379. Remediated by British History Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Stow, John. The annales of England Faithfully collected out of the most autenticall authors, records, and other monuments of antiquitie, lately collected, since encreased, and continued, from the first habitation vntill this present yeare 1605. London: Peter Short, Felix Kingston, and George Eld, 1605. STC 23337.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Streitberger, W.R. The Masters of the Revels and Elizabeth I’s Court Theatre. (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2016). Remediated by Google Books.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Summerson, John. Architecture in Britain, 1530-1830. New Haven: Yale UP, 1993. Remediated by Google Books.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

The Close Rolls of the Reign of Henry III. Preserved in the Public Record Office. A.D. 1227-1231: Printed Under the Superintendence of the Deputy Keeper of the Records. Vol. 1. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1902. Remediated by Internet Archive.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

The Lost Tiltyard Tower.

Historic Royal Palaces. December 2015. https://blog.hrp.org.uk/the-lost-tiltyard-tower/.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Thurley, Simon.Henry VIII and the Building of Hampton Court: A Reconstruction of the Tudor Palace.

Architectural History 31 (1988): 1-57. doi:10.2307/1568535.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Venice: March 1514.

Calendar of State Relating to English Affairs in the Archives of Venice, Volume 2, 1509-1519. Ed.Rawdon Brown. London: H.M. Stationery Office, 1867. Remediated by British History Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Warnicke, Retha M.Katherine [Katherine Howard] (1518x24–1542).

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H.C.G. Matthew, Brian Harrison, Lawrence Goldman, and David Cannadine. Oxford UP. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/4892.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Wiggins, Martin. Drama and the Transfer of Power in Renaissance England. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2012. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Wormald, Jenny.James VI and I (1566–1625).

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H.C.G. Matthew, Brian Harrison, Lawrence Goldman, and David Cannadine. Oxford UP. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/14592.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Wriothesley, Charles. A Chronicle of England During the Reigns of the Tudors, A.D. 1485 to 1559. Vol. 1. Ed. Hamilton, William Douglas. Westminster: J.B. Nichols and Sons, 1838. Redmediated by Internet Archive.This item is cited in the following documents:

Cite this page

MLA citation

.

Hampton Court.The Map of Early Modern London, Edition 7.0, edited by , U of Victoria, 05 May 2022, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/HAMP1.htm.

Chicago citation

.

Hampton Court.The Map of Early Modern London, Edition 7.0. Ed. . Victoria: University of Victoria. Accessed May 05, 2022. mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/HAMP1.htm.

APA citation

2022. Hampton Court. In (Ed), The Map of Early Modern London (Edition 7.0). Victoria: University of Victoria. Retrieved from https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/editions/7.0/HAMP1.htm.

RIS file (for RefMan, RefWorks, EndNote etc.)

Provider: University of Victoria Database: The Map of Early Modern London Content: text/plain; charset="utf-8" TY - ELEC A1 - Mamolite, Lauren ED - Jenstad, Janelle T1 - Hampton Court T2 - The Map of Early Modern London ET - 7.0 PY - 2022 DA - 2022/05/05 CY - Victoria PB - University of Victoria LA - English UR - https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/HAMP1.htm UR - https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/xml/standalone/HAMP1.xml ER -

TEI citation

<bibl type="mla"><author><name ref="#MAMO1"><surname>Mamolite</surname>, <forename>Lauren</forename></name></author>.

<title level="a">Hampton Court</title>. <title level="m">The Map of Early Modern London</title>,

Edition <edition>7.0</edition>, edited by <editor><name ref="#JENS1"><forename>Janelle</forename>

<surname>Jenstad</surname></name></editor>, <publisher>U of Victoria</publisher>,

<date when="2022-05-05">05 May 2022</date>, <ref target="https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/HAMP1.htm">mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/HAMP1.htm</ref>.</bibl>

Personography

-

Molly Rothwell

MR

Project Manager, 2022-present. Research Assistant, 2020-2022. Molly Rothwell was an undergraduate student at the University of Victoria, with a double major in English and History. During her time at MoEML, Molly primarily worked on encoding and transcribing the 1598 and 1633 editions of Stow’s Survey, adding toponyms to MoEML’s Gazetteer, researching England’s early-modern court system, and standardizing MoEML’s Mapography.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Molly Rothwell is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Molly Rothwell is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kate LeBere

KL

Project Manager, 2020-2021. Assistant Project Manager, 2019-2020. Research Assistant, 2018-2020. Kate LeBere completed her BA (Hons.) in History and English at the University of Victoria in 2020. She published papers in The Corvette (2018), The Albatross (2019), and PLVS VLTRA (2020) and presented at the English Undergraduate Conference (2019), Qualicum History Conference (2020), and the Digital Humanities Summer Institute’s Project Management in the Humanities Conference (2021). While her primary research focus was sixteenth and seventeenth century England, she completed her honours thesis on Soviet ballet during the Russian Cultural Revolution. During her time at MoEML, Kate made significant contributions to the 1598 and 1633 editions of Stow’s Survey of London, old-spelling anthology of mayoral shows, and old-spelling library texts. She authored the MoEML’s first Project Management Manual andquickstart

guidelines for new employees and helped standardize the Personography and Bibliography. She is currently a student at the University of British Columbia’s iSchool, working on her masters in library and information science.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Kate LeBere is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Kate LeBere is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Joey Takeda

JT

Programmer, 2018-present. Junior Programmer, 2015-2017. Research Assistant, 2014-2017. Joey Takeda was a graduate student at the University of British Columbia in the Department of English (Science and Technology research stream). He completed his BA honours in English (with a minor in Women’s Studies) at the University of Victoria in 2016. His primary research interests included diasporic and indigenous Canadian and American literature, critical theory, cultural studies, and the digital humanities.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Junior Programmer

-

Markup Editor

-

Post-Conversion Editor

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Joey Takeda is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Joey Takeda is mentioned in the following documents:

Joey Takeda authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Jenstad, Janelle and Joseph Takeda.

Making the RA Matter: Pedagogy, Interface, and Practices.

Making Things and Drawing Boundaries: Experiments in the Digital Humanities. Ed. Jentery Sayers. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2018. Print.

-

-

Cameron Butt

CB

Research Assistant, 2012–2013. Cameron Butt completed his undergraduate honours degree in English at the University of Victoria in 2013. He minored in French and has a keen interest in Shakespeare, film, media studies, popular culture, and the geohumanities.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Encoder

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Cameron Butt is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Cameron Butt is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Janelle Jenstad

JJ

Janelle Jenstad is Associate Professor of English at the University of Victoria, Director of The Map of Early Modern London, and PI of Linked Early Modern Drama Online. She has taught at Queen’s University, the Summer Academy at the Stratford Festival, the University of Windsor, and the University of Victoria. With Jennifer Roberts-Smith and Mark Kaethler, she co-edited Shakespeare’s Language in Digital Media (Routledge). She has prepared a documentary edition of John Stow’s A Survey of London (1598 text) for MoEML and is currently editing The Merchant of Venice (with Stephen Wittek) and Heywood’s 2 If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody for DRE. Her articles have appeared in Digital Humanities Quarterly, Renaissance and Reformation,Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Early Modern Literary Studies, Elizabethan Theatre, Shakespeare Bulletin: A Journal of Performance Criticism, and The Silver Society Journal. Her book chapters have appeared (or will appear) in Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society (Brill, 2004), Shakespeare, Language and the Stage, The Fifth Wall: Approaches to Shakespeare from Criticism, Performance and Theatre Studies (Arden/Thomson Learning, 2005), Approaches to Teaching Othello (Modern Language Association, 2005), Performing Maternity in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2007), New Directions in the Geohumanities: Art, Text, and History at the Edge of Place (Routledge, 2011), Early Modern Studies and the Digital Turn (Iter, 2016), Teaching Early Modern English Literature from the Archives (MLA, 2015), Placing Names: Enriching and Integrating Gazetteers (Indiana, 2016), Making Things and Drawing Boundaries (Minnesota, 2017), and Rethinking Shakespeare’s Source Study: Audiences, Authors, and Digital Technologies (Routledge, 2018).Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Author (Preface)

-

Author of Preface

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Course Instructor

-

Course Supervisor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Peer Reviewer

-

Project Director

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Janelle Jenstad is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Janelle Jenstad is mentioned in the following documents:

Janelle Jenstad authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Jenstad, Janelle and Joseph Takeda.

Making the RA Matter: Pedagogy, Interface, and Practices.

Making Things and Drawing Boundaries: Experiments in the Digital Humanities. Ed. Jentery Sayers. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2018. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Building a Gazetteer for Early Modern London, 1550-1650.

Placing Names. Ed. Merrick Lex Berman, Ruth Mostern, and Humphrey Southall. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 2016. 129-145. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

The Burse and the Merchant’s Purse: Coin, Credit, and the Nation in Heywood’s 2 If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody.

The Elizabethan Theatre XV. Ed. C.E. McGee and A.L. Magnusson. Toronto: P.D. Meany, 2002. 181–202. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Early Modern Literary Studies 8.2 (2002): 5.1–26..The City Cannot Hold You

: Social Conversion in the Goldsmith’s Shop. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

The Silver Society Journal 10 (1998): 40–43.The Gouldesmythes Storehowse

: Early Evidence for Specialisation. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Lying-in Like a Countess: The Lisle Letters, the Cecil Family, and A Chaste Maid in Cheapside.

Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 34 (2004): 373–403. doi:10.1215/10829636–34–2–373. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Public Glory, Private Gilt: The Goldsmiths’ Company and the Spectacle of Punishment.

Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society. Ed. Anne Goldgar and Robert Frost. Leiden: Brill, 2004. 191–217. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Smock Secrets: Birth and Women’s Mysteries on the Early Modern Stage.

Performing Maternity in Early Modern England. Ed. Katherine Moncrief and Kathryn McPherson. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007. 87–99. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Using Early Modern Maps in Literary Studies: Views and Caveats from London.

GeoHumanities: Art, History, Text at the Edge of Place. Ed. Michael Dear, James Ketchum, Sarah Luria, and Doug Richardson. London: Routledge, 2011. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Versioning John Stow’s A Survey of London, or, What’s New in 1618 and 1633?.

Janelle Jenstad Blog. https://janellejenstad.com/2013/03/20/versioning-john-stows-a-survey-of-london-or-whats-new-in-1618-and-1633/. -

Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. Ed. Janelle Jenstad. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/MV/.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ & nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. Ed. Janelle Jenstad and the MoEML Team. MoEML. Transcribed.

-

-

Roles played in the project

-

Author

Contributions by this author

Lauren Mamolite is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Martin D. Holmes

MDH

Programmer at the University of Victoria Humanities Computing and Media Centre (HCMC). Martin ported the MOL project from its original PHP incarnation to a pure eXist database implementation in the fall of 2011. Since then, he has been lead programmer on the project and has also been responsible for maintaining the project schemas. He was a co-applicant on MoEML’s 2012 SSHRC Insight Grant.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Conceptor

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Post-Conversion Editor

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

Contributions by this author

Martin D. Holmes is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Martin D. Holmes is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Anne Boleyn is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Catherine of Aragon is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Francis Beaumont is mentioned in the following documents:

Francis Beaumont authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Beaumont, Frances.

Letter from Beaumont to Ben Jonson.

The Dramatic Works of Beaumont and Fletcher. London: John Stockdale, 1811. Remediated by Hathi Trust. -

Beaumont, Francis. The Knight of the Burning Pestle. Ed. Sheldon P. Zitner. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2004. Print.

-

Anne of Cleves is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Samuel Daniel is mentioned in the following documents:

Samuel Daniel authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Daniel, Samuel. The order and solemnitie of the creation of the High and mightie Prince Henrie, eldest sonne to our sacred soueraigne, Prince of VVales, Duke of Cornewall, Earle of Chester, &c. as it was celebrated in the Parliament House, on Munday the fourth of Iunne last past. Together with the ceremonies of the Knights of the Bath, and other matters of speciall regard, incident to the same. Whereunto is annexed the royall maske, presented by the Queene and her ladies, on Wednesday at night following. London: William Stansby for John Budge, 1610. STC 13161.

-

Daniel, Samuel. The Vision of the 12 Goddesses, Presented in a Maske the 8 of January, at Hampton Court by the Queenes Most Excellent Majestie, and her Ladies. London: T. C. for Simon Waterson, 1604. STC 6265.

-

Edward III

Edward This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 3III King of England

(b. 12 November 1312, d. 21 June 1377)Edward III is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Edward VI

Edward This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 6VI King of England King of Ireland

(b. 12 October 1537, d. 6 July 1553)Edward VI is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 1I Queen of England Queen of Ireland Gloriana Good Queen Bess

(b. 7 September 1533, d. 24 March 1603)Queen of England and Ireland 1558-1603.Elizabeth I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell Lord Protector

(b. 25 April 1599, d. 3 September 1658)Soldier, statesman, and Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Led the parliamentary forces in the English Civil Wars.Oliver Cromwell is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Jane Seymour

Jane Seymour Queen consort of England

(b. 1508, d. 24 October 1537)Queen consort of England 1536-1537. Third wife of Henry VIII. Mother of King Edward VI. Not to be confused with Jane Seymour.Jane Seymour is mentioned in the following documents:

Jane Seymour authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Seymour, Jane.

12 Oct 1537: Seymour, Jane, Queen consort of Henry VIII, 1508-1537 (Hampton Court Palace, Richmond upon Thames, London, England) to Privy Council to Henry VIII, King of England, 1509-1547.

Oxford: Bodleian Library, 1537. Remediated by Early Modern Letters Online.

-

Giles Daubeney

(b. 1 June 1451, d. 21 May 1508)First Baron Daubeney. Soldier, diplomat, and privy councilor to Henry VII. Buried at Westminster Abbey.Giles Daubeney is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Henrietta Maria

Henrietta Maria Queen consort of England Queen consort of Scotland Queen consort of Ireland

(b. 1609, d. 1669)Henrietta Maria is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Henry VIII

Henry This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 8VIII King of England King of Ireland

(b. 28 June 1491, d. 28 January 1547)King of England and Ireland 1509-1547.Henry VIII is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Henry VII

Henry This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 7VII King of England

(b. 1457, d. 1509)Henry VII is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Henry III

Henry This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 3III King of England

(b. 1 October 1207, d. 16 November 1272)Henry III is mentioned in the following documents:

-

James VI and I

James This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 6VI This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 1I King of Scotland King of England King of Ireland

(b. 1566, d. 1625)James VI and I is mentioned in the following documents:

James VI and I authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

James VI and I. Letters of King James VI and I. Ed. G.P.V. Akrigg. Berkeley: U of California P, 1984. Print.

-

Rhodes, Neill, Jennifer Richards, and Joseph Marshall, eds. King James VI and I: Selected Writings. By James VI and I. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004.

-

Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary Queen of Scotland

(b. 1542, d. 1587)Queen of Scotland 1542-1567. Queen of France 1559-1560.Mary, Queen of Scots is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Mary I

Mary This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 1I Queen of England Queen of Ireland

(b. 18 February 1516, d. 17 November 1558)Mary I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Mary of Guise is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Norden is mentioned in the following documents:

John Norden authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Norden, John, John Speed, and Jodocus Honidus.

Middle-sex Described with the Most Famous Cities of London and Westminster.

The Theatre of the Empire of Greant Britaine. By John Speed. London: George Humble, 1611. Insert after sig. H2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Norden, John.

London

[map.] London, 1593. Reprinted in 1653 with an index entitledA Guide for Cuntrey men In the famous Cittey of London by the help of which plot they shall be able to know how farr it is to any street. As allso to go unto the same without forder troble.

London: P. Stent, 1653. British Library. -

Norden, John.

London.

Speculum Britanniae. The first parte an historicall, & chorographicall discription of Middlesex. Wherin are also alphabeticallie sett downe, the names of the cyties, townes,parishes hamletes, howses of name &c. W.th direction spedelie to finde anie place desiredin the mappe & the distance betwene place and place without compasses. By Norden, John. London: Eliot’s CourtP, 1593. Insert between sig. E1v and sig. E2r. [See more information about this map.]

-

Alexander Pope is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Edward Seymour is mentioned in the following documents:

-

William Shakespeare is mentioned in the following documents:

William Shakespeare authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. 1998. Remediated by Project Gutenberg.

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. Ed. Vittorio Gabrieli and Giorgio Melchiori. Revels Plays. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1990. Print.

-

Shakespeare, William. All’s Well That Ends Well. Ed. Helen Ostovich. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/AWW/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Antony and Cleopatra. Ed. Randall Martin. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Ant/.

-

Shakespeare, William. As You Like It. Ed. David Bevington. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/AYL/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Comedy of Errors. Ed. Matthew Steggle. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Err/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Coriolanus. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Cor/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Cymbeline. Ed. Jennifer Forsyth. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Cym/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Edward III. Ed. Jennifer Massai. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Edw/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The first part of the contention betwixt the two famous houses of Yorke and Lancaster with the death of the good Duke Humphrey: and the banishment and death of the Duke of Suffolke, and the tragicall end of the proud Cardinall of VVinchester, vvith the notable rebellion of Iacke Cade: and the Duke of Yorkes first claime vnto the crowne. London, 1594. STC 26099.

-

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. Ed. David Bevington. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Ham/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry IV, Part 1. Ed. Rosemary Gaby. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/1H4/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry IV, Part 2. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/2H4/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry V. Ed. James D. Mardock. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/H5/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry VIII. Ed. Diane Jakacki. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/H8/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry VI, Part 1. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/1H6/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry VI, Part 2. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/2H6/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry VI, Part 3. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/3H6/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Julius Caesar. Ed. John D. Cox. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/JC/.

-

Shakespeare, William. King John. Ed. Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Jn/.

-

Shakespeare, William. King Lear. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 1201–54.

-

Shakespeare, William. King Lear. Ed. Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Lr/.

-

Shakespeare, William. King Richard III. Ed. James R. Siemon. London: Methuen, 2009. The Arden Shakespeare.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Life of King Henry the Eighth. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 919–64.

-

Shakespeare, William. A Lover’s Complaint. Ed. Hardy M. Cook. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/lC/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Love’s Labor’s Lost. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/LLL/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Macbeth. Ed. Anthony Dawson. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Mac/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Measure for Measure. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 414–454.

-

Shakespeare, William. Measure for Measure. Ed. Herbert Weil. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/MM/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. Ed. Janelle Jenstad. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/MV/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Merry Wives of Windsor. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Wiv/.

-

Shakespeare, William. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Ed. Suzanne Westfall. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/MND/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Mr. VVilliam Shakespeares comedies, histories, & tragedies Published according to the true originall copies. London, 1623. STC 22273.

-

Shakespeare, William. Much Ado About Nothing. Ed. Grechen Minton. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Ado/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Othello. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Oth/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Passionate Pilgrim. Ed. Hardy M. Cook. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/PP/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Pericles. Ed. Tom Bishop. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Per/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Phoenix and the Turtle. Ed. Hardy M. Cook. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/PhT/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Rape of Lucrece. Ed. Hardy M. Cook. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Luc/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Richard II. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 740–83.

-

Shakespeare, William. Richard II. Ed. Catherine Lisak. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/R2/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Richard the Third (Modern). Ed. Adrian Kiernander. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/R3/.

-