The Globe

¶Location

The Globe was built in the district of Bankside, in the Borough of Southwark. The Globe was located in London, south of Maiden Lane, on what is now Park Street in London (McCudden 143). Archaeological findings place the Globe due southeast of the Rose and about 115 metres south of the Thames River. It originally stood in an area just south of Maiden Lane. It lay west of modern-day Porter Street.

¶History

The Globe was originally built in Bankside, Southwark in 1599. The Lord Chamberlain’s Men, led by Richard Burbage and by his father, James Burbage, before him, had been performing at the Theatre, which had been built by the Burbage family on land leased from Giles Allen. In 1597, Allen refused to renew the lease, and although James Burbage had purchased the Blackfriars in 1596, with the plan of using it as an indoor theatre, the wealthy residents of the Blackfriars neighborhood had prevented that from happening. James Burbage died in 1597, leaving the Theatre and the Blackfriars to his sons, Cuthbert and Richard. With Allen’s refusal to renew their lease, however, the Chamberlain’s Men were left without a useable theatre, and they were forced to rent the Curtain. But while Allen owned the land on which the Theatre was built, the terms of the lease actually gave the Burbages the right to dismantle

and move what they had built on it. Therefore, in December of 1598, while Giles Allen was out of town, they dismantled the Theatre and transported the lumber across the river. Their builder, Peter Streete, stored the lumber for them until the Chamberlain’s Men leased land in Bankside, near their competitor, the Rose theatre, and used the timbers from the Theatre to build the Globe.

Because the Chamberlain’s Men were in difficult financial straits, the first Globe was built using cheaper materials. The roof, for instance, was thatched with reeds

rather than being covered in tile. This would prove to be the demise of the first

Globe. In 1613, during a performance of Shakespeare’s Henry VIII, a prop cannon was fired. Although the cannon did not actually contain a cannon ball,

it did contain gunpowder, packed down with wadding. A piece of this wadding landed

on the roof and the thatch caught fire. Within an hour, the Globe had burnt to the ground. Poet and playwright Ben Jonson commented on this event in his poem,

An Execration upon Vulcan:

But oh these Reeds, thy meere disdaine of them,Made thee beget that cruell stratagem:(Which some are pleas’d to stile but thy mad prank)Against the Globe, the glory of the banke,VVhich though it were the Fort of the whol parish,Fenc’d with a Ditch and forkt out of a Marish:I saw with two poore Chambers taken in,And rais’d ere thought could urge: this might have bin.See the worlds ruines, nothing but the piles.Left, and wit since to covet it with tiles(Jonson sig. B3v)

The King’s Men, as the company was then called, rebuilt the Globe, and since their finances were now much better, they did have the

wit Gap in transcription. Reason: ()[…] to cover it with tiles.The second Globe had a tile roof and was more extravagantly decorated. The Globe continued to be a successful venue, albeit mostly a summer venue, until 1642, when all the London theatres were closed (Egan; Gurr).

The Fire at the Globe, 1613by Cyril Walter Hodges. Image courtesy of the Folger Digital Image Collection.

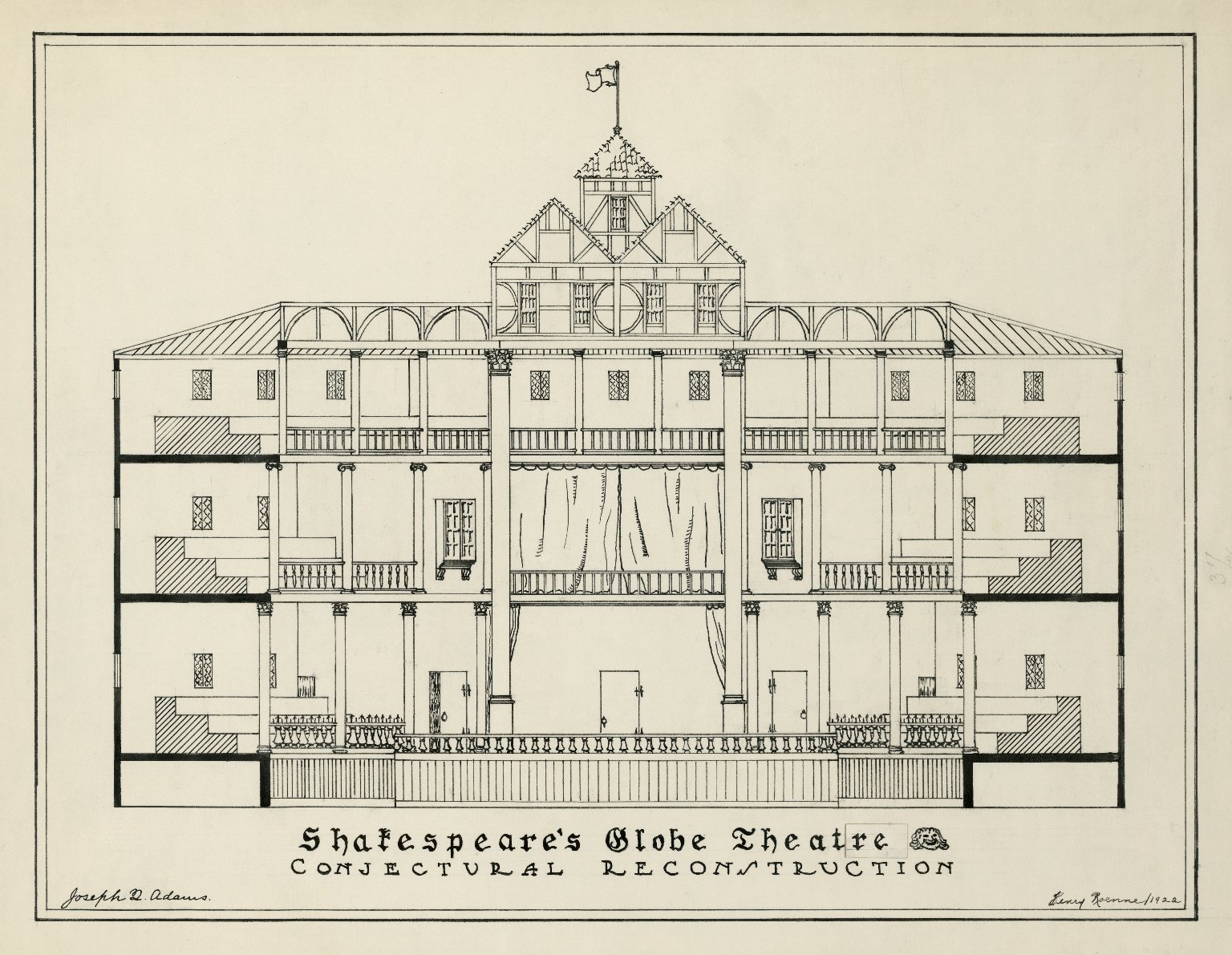

¶Architecture and Archeology

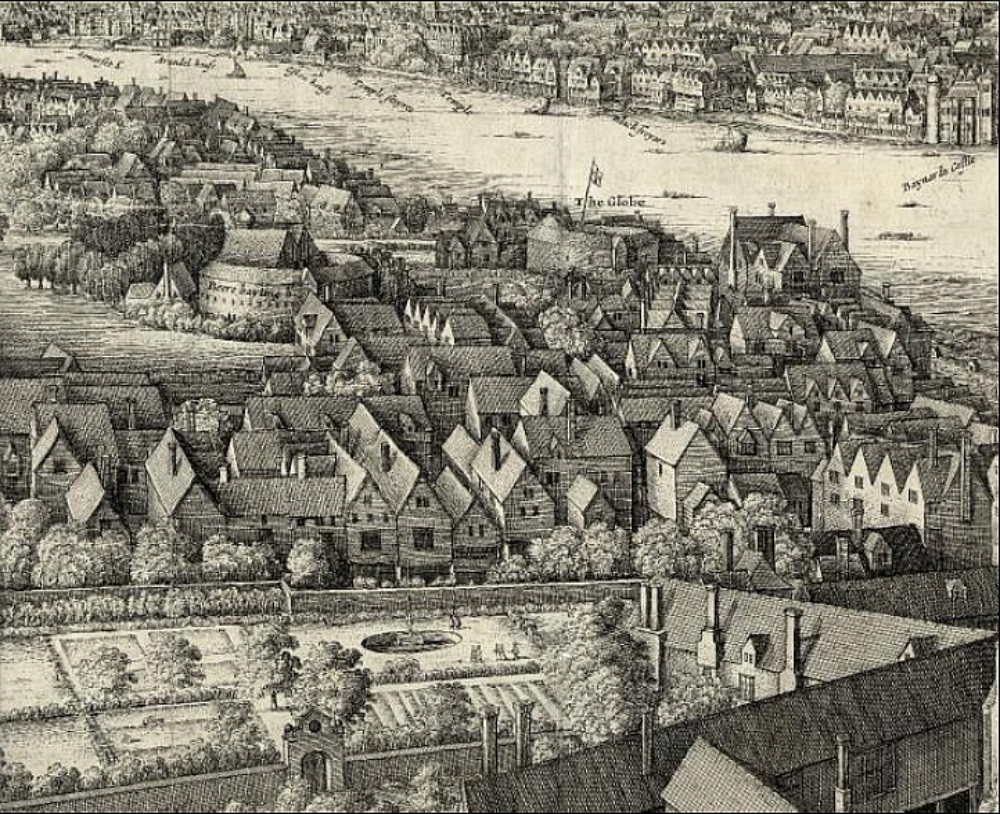

There is much uncertainly surrounding the specific architectural details of the Globe. For instance, scholars debate the actual size and shape of the famous theatre. Initially

scholars attempted to extrapolate the dimensions and shape of the playhouse from etchings,

more specifically, etchings from the Bohemian artist Wencelaus Hollar. In the western section of the

Long View of London from Bankside(1647), an etching created by Hollar that surveys the London landscape,the Globe is prominently featured along the river bank (Hollar; Hodges 11). Although Hollar confuses the Globe Theatre with the nearby bearbaiting enclosure and mislabels both, scholars still speculated about the size and shape of the playhouse by comparing Hollar’s depiction of the theatre with the dimensions of other well known buildings in the landscape at the time. Based on this pictorial evidence, Cyril Walter Hodges, experienced illustrator and Shakespearean scholar, argued that the playhouse had sixteen sides, though he admitted that it might have had twelve (Hodges 45). He also determined that the playhouse was about 31 feet high and 92 feet in diameter (Hodges 49).

London from Banksideby Wenceslaus Hollar. The labels on the Globe and the bear-baiting ring have been switched. Image courtesy of the Folger Digital Image Collection.

Architectural scholarship on the Globe Theatre was shaken by the discovery of a fraction of the playhouse’s original foundation

in 1989 (McCudden 143). During 1988–1991 a significant archaeological dig was performed at what was purported

through historical documentation to be the original sites of the Rose and Globe theatres. The dig uncovered what has proved to be definitive evidence of the existence

of both theatres. Although most of the remains of the Rose were uncovered, the Globe’s unearthed remains only showed a few yards of the outer walls of the theater (Bowsher and Miller xiv). The Globe site could not be fully excavated due to existing architectural and civic concerns

(Gurr 400-401). Archeologists excavated the north-east portion of the theatre, a space

approximately 12m X 9m 140ft X 30ftof the Globe (McCudden 143). The excavation of a portion of the Globe revealed that the structure was supported by three parallel walled foundations. The two outer walls were created using interlaced brick, while the inner wall was formed from timber and a chalk motar (McCudden 143).

Even after this archeological discovery, scholars remain uncertain about the exact

shape and dimensions of the theatre. Archaeologist Simon McCudden and prominent Shakespeare

scholar Andrew Gurr have both suggested that the Globe had twenty sides, but others have argued that it had either sixteen or eighteen sides

(McCudden 144; Gurr 97; Bowsher and Miller 126-129).

While there is not universal agreement on the size and shape of the Globe, the archaeological dig did reveal much about the materials used in the playhouse.

It is assumed that peg tiles were used on the 1614 roof from what little demolition remains were recovered (Bowsher and Miller 116-117). Mortar/plaster substances and peg tiles from the inner area of the uncovered wall

remains led experts to theorize that the 1614 structure used these materials in wall constructions (Bowsher and Miller 113). The foundations of the 1599 Globe appear to have consisted chiefly of chalk rubble mixtures, while the 1614 structure had a brick foundation with supportive peg tiles inlaid between the bricks

(Bowsher and Miller 113).

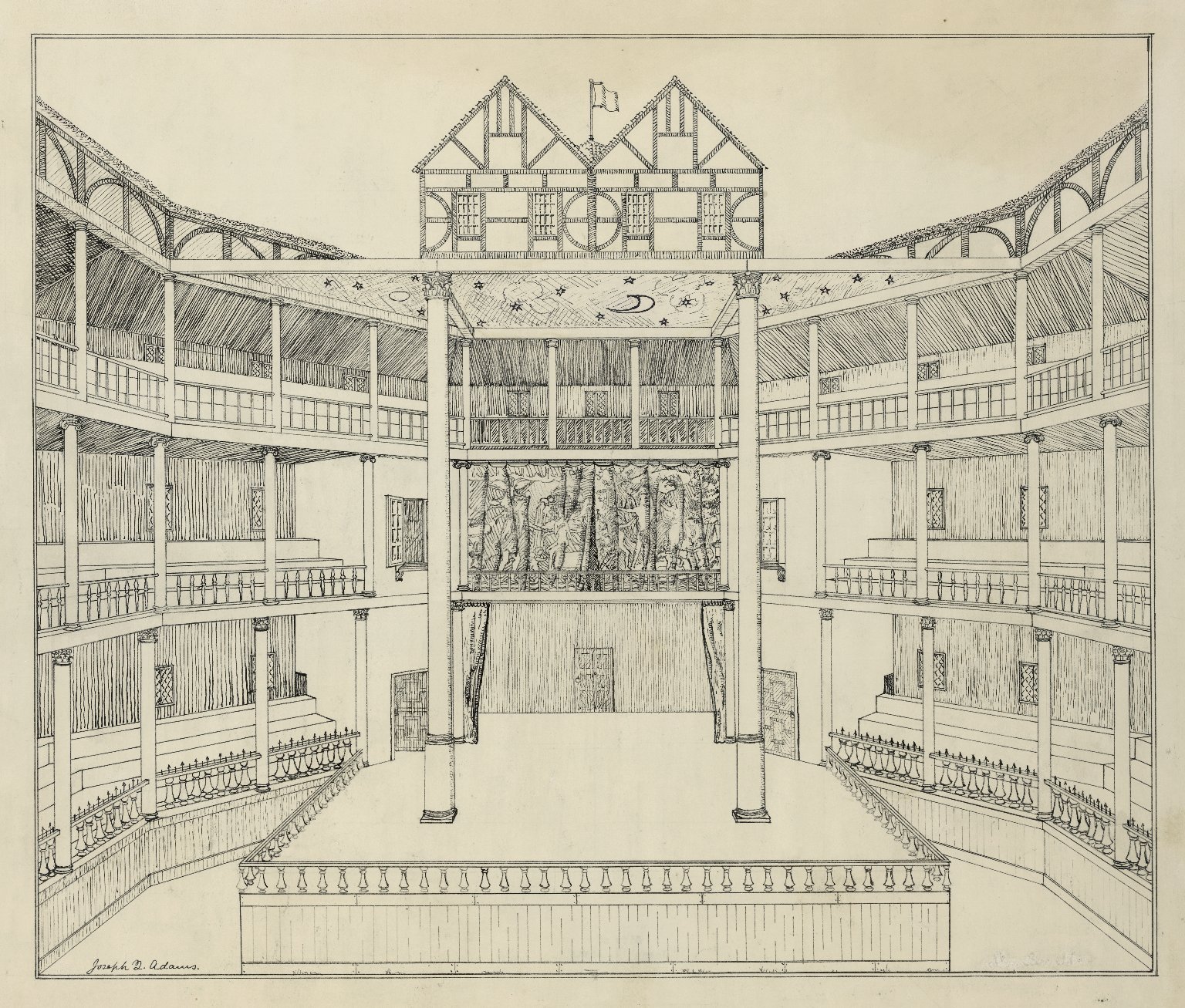

Although scholars do not agree on the exact shape and size of the Globe Theatre, we know that the playhouse was an open air amphitheater surrounded by a three-story

gallery overhang, which could hold around three-thousand people. In the centre was

a thrust stage, and an area called the

pitor

yardwhere audience members could stand and watch the drama. A roof over the stage was supported by columns or stage trees (Hodges 49; Egan).

Unlike other theatres of the time, the Globe used two stair turrets to provide access

to the galleries. Archeologists excavated one of the stair turrets in an archaeological

dig in 1989. The foundation for the turret was built with chalk mortar, or

clunchwhich formed the base of the outer walls, and attached to surrounding brick work (Gurr 97).

The discovery of these stair turrets presented theatre historians with a new admission

system than they had seen employed in playhouses previously. Other theatres, such

as the Rose, used a system of gates where one payment would be made at the entrance gate, another

payment would allow audience members to enter the scaffolds, and a third was for

quiet standing(Gurr 99). This design required the theatre to create three or four lobbies or gatherers in order for patrons to access various areas of the theatre. The Globe’s use of the stair turrets allowed the theatre company to employ only two main lobbies from which patrons could access the either the yard or the galleries. This system allowed the company to economize on the space within the theatre and gain higher profits (Gurr 99). Furthermore, the stairwell ensured that only the patrons who had paid more accessed the galleries. Those who had paid only to stand in the yard went in one direction, while the audience members who had paid for a seat in the galleries went in the other direction, and up the stairs (Gurr 99).

These conclusions have been drawn from the section of the Globe that archeologists were able to excavate. Archeologists believe the remains of the

theatre continue underneath various present-day structures such as the Barclay-Perkins

Brewery (Orser 253). Although there are parts of the foundation that continue to the east, the majority

of the remains continue westward (Orser 254).

¶Playing Companies

Because the 1572

Acte for the punishment of Vagabondesand a similar but more restrictive 1598 statute declared that actors or players who did not work for a patron, or

Personage of higher degree,could be declared beggars or vagabonds and placed in a workhouse, actors in late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries had to be part of a group of players sponsored by a member of the nobility (Gurr 27). The company that performed at the Globe, and which Shakespeare was a part of, was the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, patronized by Henry Carey, the Lord Chamberlain. In 1603 they became the King’s Men, with King James serving as their patron (Best; Gurr 28). They were one of the leading companies of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries (Best; Dutton 73; Gurr 41-49).

The playing companies were usually made up of sharers, or members who shared in both

the profits and expenses of the company, and hirelings, who were paid on a weekly

basis. However, when the Burbages found themselves in need of a new theatre for the

Chamberlain’s Men and with limited financial resources, they created a new type of shareholder. The

Burbages paid fifty per cent of the cost of building the Globe, and their five sharers, Shakespeare, Heminges, Kempe, Phillps, and Pope each paid 10 per cent. This innovation made the players not only sharers in the profits

and expenses of the playhouse but also housekeepers or landlords, who earned a share

of the half of the gallery takings that were usually the right of the owners. Kempe later left the partnership, giving each of the remaining sharers an increased share

(Gurr 44-46).

Players and companies of players contended with many difficulties. If they were not

sponsored by a member of the nobility, actors could be declared vagabonds. If an epidemic

of the plague broke out in London, the London theatres would be closed and the companies would have to travel, which was generally

less profitable (Gurr 28-29). Additionally, companies had to receive a license from the Master of the Revels

in order to perform or print any play. While this license sometimes gave the companies

a certain protection from local authorities, it also meant that performing plays that

contained offensive materials such as satirical religious or political contents could

result in the punishment of the transgressing companies and their actors (Best; Gurr 73-77). The Chamberlain’s Men and the King’s Men were censored and punished on more than one occasion. For instance, in 1601, the performance of Shakespeare’s Richard II by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men at the Globe the night before the Essex rebellion resulted in paying a fine of 40 shillings (McCrea 175). Another example of the censorship and punishment resulted from the performance

of Thomas Middleton’s A Game at Chess in 1624 by the King’s Men at the Globe. This play contained offensive political contents; it portrayed a Christian king

on the stage, which was illegal at that time. As a result of this offensive performance,

the Globe was closed and Thomas Middleton, the playwright, and other actors were scolded and fined (Howard-Hill 104).

¶Players

The players of the Globe, like most actors of the time, had an unusual role in society—though most were deemed

rogues and scoundrels in everyday life, they somehow flourished professionally. Some

of the players achieved high respect among the gentry and nobility. For example, tragedian

Richard Burbage was a friend of the Earl of Pembroke, a powerful and wealthy nobleman (Gurr 86).

The First Folio of Shakespeare records the name of twenty six

of the principal actors in all these plays: William Shakespeare; Richard Burbage; John Heminges; Augustine Phillips; William Kempe; Thomas Pope; George Bryan; Henry Condell; William Sly; Richard Cowley; John Lowin; Samuel Crosse; Alexander Cooke; Samuel Gilburne; Robert Armin; William Ostler; Nathan Field; John Underwood; Nicholas Tooley; William Ecclestone; Joseph Taylor; Robert Benfield; Robert Gouge; Richard Robinson; John Schanke; and John Rice (Shakespeare). Many of these actors would have performed at the Globe. Of these, a few deserve special note.

Richard Burbage (1567-1619) was arguably the most notable of the tragedians in the Chamberlain’s Men. He was instrumental in the 1598 disassembly of the Theatre and subsequent building of the Globe. He and his brother, Cuthbert, held a 50% share in the Globe. Burbage’s roles included those of Hamlet, King Lear, Richard III, Jeronimo, and Othello, and he is listed as a player for every play in the King’s Men’s repertoire from 1599 to 1618 for which lists of players survive (Gurr 91).

Robert Armin was perhaps the best known of the Globe’s comic actors. Though his predecessor in the Chamberlain’s Men, Will Kempe, was equally skilled in a very different type of comedy, he left the company in 1599, and it is unlikely that he ever performed at the Globe (Gurr 44; Pignataro 78). Armin was not a handsome man. His appearance made him unsuitable for a tragic lead role,

but because his intellectual and witty style of fooling, Shakespeare wrote characters such as Feste in Twelfth Night and King Lear’s Fool for Armin (Gurr 89; Pignataro 78-79).

¶Plays Performed

The majority of Shakespeare’s plays are recorded as having been performed at the Globe. In fact, many scholars believe that the first play to open in the Globe was Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar (Pignataro 78). Not directly associated with the Globe are Shakespeare’s early histories and comedies. These include all three parts of Henry VI, The Merchant of Venice, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Much Ado About Nothing, and Richard III (Gurr 236-241). The Tempest is also not directly associated with the Globe (Gurr 241), but perhaps because by the time of this late play, the Globe was primarily a summer venue. The lack of documentation, however, does not necessarily

mean that these plays were not performed at the Globe (Gurr 232).

While the Globe is now famously associated with Shakespeare, his plays were not the only ones performed there. Another play performed in the

Globe’s opening season was the now lost Cloth Breeches and Velvet Hose (Knutson 63), a dramatization of an allegorical story by Robert Greene that warns against the dangers of luxury (Knutson 61). A second allegorical play, A Larum for London, depicting a sinful village under siege by an army symbolic of the scourge of God,

is cited by both Knutson and Gurr as having been performed at the Globe (Knutson 63-72; Gurr 238).

The Globe did not favor one play or playwright for long. Shakespeare’s plays were performed quite often, but the popularity and reception of a play was

important. If a play was popular and brought in an audience, then the Globe would bring in money. To bring in audiences, plays were seldom performed consecutively.

Instead there might be six plays, by different playwrights, performed in a week (Watkins and Lemmon 22). If the Globe changed the play every night, then it was likely they would draw in an audience every

night.

The list of playwrights whose plays were performed at the Globe is extensive, and includes the names of some of the great playwrights of the time.

Some of the playwrights whose plays are known to have been played at the Globe include Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher, John Ford, Philip Massinger, Richard Brome, and John Webster. It is clear that although Shakespeare is the playwright most associated with the Globe many other playwrights have made the Globe the theater in which their works have come to life.

While we have no record of all the plays performed at the Globe, the Database of Early English Playbooks (DEEP) records that the plays in the following chart were published with a title page attribution

declaring that the play had been performed at the Globe. The

yearin the first column refers to the year of the publication including this title page attribution.

| Year | Author | Title | First Publication | First Production | DEEP Number |

| 1608 | William Shakespeare | Richard the Second | 1597 | 1595 | DEEP 222 |

| 1608 | Anonymous | The Merry Devil of Edmonton | 1608 | 1602 | DEEP 509 |

| 1608 | William Shakespeare | King Lear | 1608 | 1605 | DEEP 515 |

| 1608 | Thomas Middleton (?) | A Yorkshire Tragedy | 1608 | 1605 | DEEP 521 |

| 1609 | William Shakespeare | Romeo and Juliet | 1597 | 1595 | DEEP 236 |

| 1609 | William Shakespeare | Troilus and Cressida | 1609 | 1602 | DEEP 536 |

| 1609 | William Shakespeare, George Wilkins | Pericles, Prince of Tyre | 1609 | 1602 | DEEP 544 |

| 1609 | William Shakespeare, George Wilkins | Pericles, Prince of Tyre | 1609 | 1608 | DEEP 545 |

| 1610 | Anonymous | Mucedorus (and Amadine) | 1598 | 1590 | DEEP 261 |

| 1611 | Anonymous | Mucedorus (and Amadine) | 1598 | 1590 | DEEP 262 |

| 1611 | William Shakespeare, George Wilkins | Pericles, Prince of Tyre | 1609 | 1608 | DEEP 546 |

| 1612 | Anonymous | The Merry Devil of Edmonton | 1608 | 1602 | DEEP 510 |

| 1613 | Anonymous | Mucedorus (and Amadine) | 1598 | 1590 | DEEP 263 |

| 1615 | William Shakespeare | Richard the Second | 1597 | 1595 | DEEP 223 |

| 1615 | Anonymous | Mucedorus (and Amadine) | 1615 | 1590 | DEEP 264 |

| 1617 | Anonymous | The Merry Devil of Edmonton | 1608 | 1602 | DEEP 511 |

| 1618 | Anonymous | Mucedorus (and Amadine) | 1598 | 1590 | DEEP 265 |

| 1619 | Anonymous | Mucedorus (and Amadine) | 1598 | 1590 | DEEP 266 |

| 1619 | William Shakespeare | King Lear | 1608 | 1605 | DEEP 516 |

| 1619 | Francis Beaumont, John Fletcher | A King and No King | 1619 | 1611 | DEEP 668 |

| 1620 | Francis Beaumont, John Fletcher | Philaster, or Love Lies a-Bleeding | 1620 | 1609 | DEEP 675 |

| 1621 | Anonymous | Mucedorus (and Amadine) | 1598 | 1590 | DEEP 267 |

| 1622 | Francis Beaumont, John Fletcher | Philaster, or Love Lies a-Bleeding | 1620 | 1609 | DEEP 677 |

| 1622 | William Shakespeare | Othello, the Moor of Venice | 1622 | 1604 | DEEP 692 |

| [1623] | William Shakespeare | Romeo and Juliet | 1597 | 1595 | DEEP 237 |

| 1623 | John Webster | The Duchess of Malfi | 1623 | 1614 | DEEP 711 |

| [1625] | Thomas Middleton | A Game at Chess | [1625] | 1624 | DEEP 722 |

| [1625?] | Thomas Middleton | A Game at Chess | [1625] | 1624 | DEEP 723 |

| [1625] | Thomas Middleton | A Game at Chess | [1625] | 1624 | DEEP 725 |

| 1626 | Anonymous | Mucedorus (and Amadine) | 1598 | 1590 | DEEP 268 |

| 1626 | Anonymous | The Merry Devil of Edmonton | 1608 | 1602 | DEEP 512 |

| 1628 | Francis Beaumont, John Fletcher | Philaster, or Love Lies a-Bleeding | 1620 | 1609 | DEEP 678 |

| 1629 | John Ford | The Lover’s Melancholy | 1629 | 1628 | DEEP 731 |

| 1630 | William Shakespeare | Othello, the Moor of Venice | 1622 | 1604 | DEEP 693 |

| 1630 | Philip Massinger | The Picture | 1630 | 1629 | DEEP 753 |

| 1631 | William Shakespeare | The Taming of the Shrew | 1594 | 1591 | DEEP 185 |

| 1631 | William Shakespeare | Love’s Labor’s Lost | 1598 | 1595 | DEEP 258 |

| 1631 | Anonymous | Mucedorus (and Amadine) | 1598 | 1590 | DEEP 270 |

| 1631 | Anonymous | The Merry Devil of Edmonton | 1608 | 1602 | DEEP 513 |

| 1632 | Philip Massinger | The Emperor of the East | 1632 | 1631 | DEEP 783 |

| 1632 | Richard Brome | The Northern Lass | 1632 | 1629 | DEEP 787 |

| 1634 | William Shakespeare | Richard the Second | 1597 | 1595 | DEEP 224 |

| 1634 | Anonymous | Mucedorus (and Amadine) | 1598 | 1590 | DEEP 271 |

| 1634 | Francis Beaumont, John Fletcher | Philaster, or Love Lies a-Bleeding | 1620 | 1609 | DEEP 679 |

| 1634 | Thomas Heywood, Richard Brome | The Late Lancashire Witches | 1634 | 1634 | DEEP 829 |

| 1636 | Thomas Heywood | A Challenge for Beauty | 1636 | 1635 | DEEP 849 |

| 1637 | William Shakespeare | Romeo and Juliet | 1597 | 1595 | DEEP 239 |

| 1639 | Anonymous | Mucedorus (and Amadine) | 1598 | 1590 | DEEP 272 |

| 1639 | Francis Beaumont, John Fletcher | Philaster, or Love Lies a-Bleeding | 1620 | 1609 | DEEP 680 |

| 1639 | Philip Massinger | The Unnatural Combat | 1639 | 1624 | DEEP 911 |

| 1639 | Henry Glapthorne | Albertus Wallenstein | 1639 | 1639 | DEEP 921 |

| 1652 | Francis Beaumont, John Fletcher | Philaster, or Love Lies a-Bleeding | 1620 | 1609 | DEEP 682 |

| 1655 | Anonymous | The Merry Devil of Edmonton | 1608 | 1602 | DEEP 514 |

| 1655 | William Shakespeare | King Lear | 1608 | 1605 | DEEP 517 |

| 1655 | William Shakespeare | Othello, the Moor of Venice | 1622 | 1604 | DEEP 694 |

| [1656?] | Anonymous | Mucedorus (and Amadine) | 1598 | 1590 | DEEP 273 |

| 1652 [1661 (?)] | Francis Beaumont, John Fletcher | Philaster, or Love Lies a-Bleeding | 1620 | 1609 | DEEP 683 |

¶Audience

Since the playhouse was in the

libertiesof London, the audience was outside of the control of potentially hostile city officials. It also meant that the audience was near other theatres, bear baiting arenas, brothels, and leper colonies. It was far from an elite neighborhood, but it was a location that gave them freedom and allowed them to attract a diverse audience. Poorer Londoners could pay a penny to stand in the yard, and wealthier theatre goers could venture across the river and pay more to sit in the galleries.

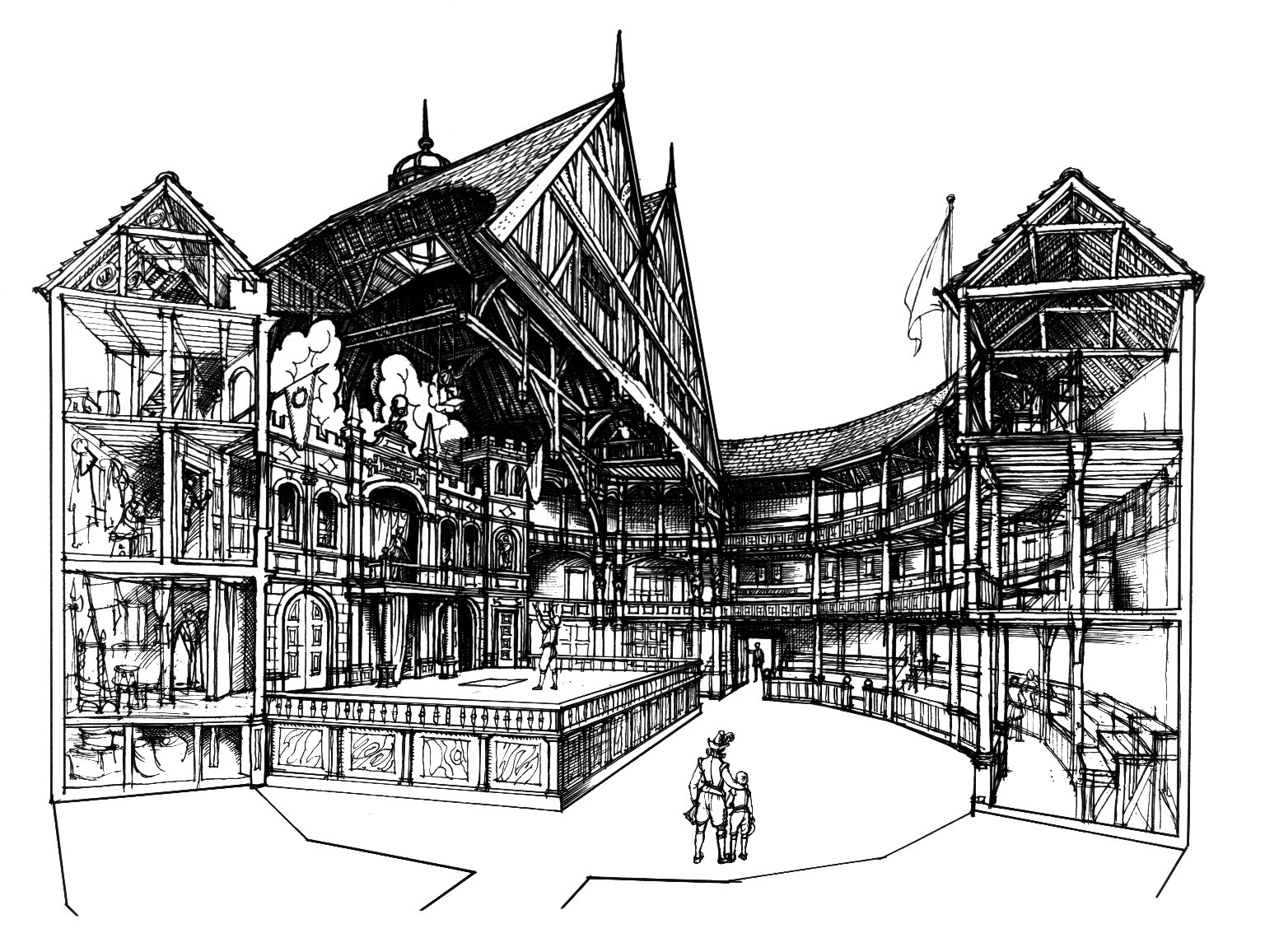

¶Modern Reconstructions

Because of its association with Shakespeare, the Globe has fascinated modern audiences, scholars, and theatre professionals. Several theatres

have been built that imitate either the exterior of the Globe, the interior of an Elizabethan playhouse, or both. Modern globe theatres exist in

Japan, Italy, Germany, England, Australia, and the United States of America (Gurr 27). Perhaps the best known of these, and possibly the most historically accurate, is

Shakespeare’s Globe, in London, England, located just a short distance from the site of the first two Globe theatres.

This modern reconstruction of the Globe was the idea of Sam Wanamaker, an American actor, director, and producer, whose first

job in the theatre was acting in a Shakespeare play in a reconstruction of the Globe at the Great Lakes World Fair in Ohio in 1936 (Shakespeare’s Globe Trust). In 1970, Wanamaker founded what would become the Shakespeare Globe Trust, which

was dedicated to the reconstruction of Shakespeare’s Globe. Sam Wanamaker died in 1993, after twenty-three years of fundraising and planning

the reconstruction alongside Theo Crosby, the Shakespeare Globe Trust architect (Gurr 32-47; Shakespeare’s Globe Trust). Unfortunately, both Wanamaker and Crosby died before the completion of the theatre;

however, the third Bankside theatre was completed in 1997 and is now a venue for performances of both Shakespearean

plays and new plays (Mulryne and Shewring 11; Shakespeare’s Globe Trust).

While the size and shape of the original Globe is uncertain, the architect, builders, and the Shakespeare Globe Trust attempted

to make the theatre as historically accurate as possible. When possible they used

the same type of materials as were used for the first Globe. They used green oak, and joined the timbers together using wooden pegs. Because

of modern safety concerns, they had to use modern scaffolding and cranes, and the

thatched roof had to be lined with fire-retardant material. The modern Globe also

had to have more exits than the original, and the theatre has to employ stewards to

look after the audience in the event of a fire or other emergency (Greenfield 81-96; Shakespeare’s Globe Trust). The modern Globe also seats fewer patrons, since modern audiences prefer to purchase

a ticket for a numbered seat rather than crowding in on the benches. Audience members

still stand in an open air yard around the stage of the new Globe (Shakespeare’s Globe Trust).

Although great effort was expended in making the new Globe as historically accurate

as possible, there is still doubt about how similar it is to the first two Globe theatres. Performance studies expert Tim Fitzpatrick argues that Wanamaker’s Globe

is larger than the original Globe. The original globe might have been 86 feet wide, while Wanamaker’s Globe measures

100 feet in diameter. Fitzpatrick has also suggested that the stage posts may have

been closer together and further upstage. The new Globe is as close an approximation

of the original Globe as was possible after years of research, debate, and speculation, but we cannot know

if it is entirely accurate. Despite any possible inaccuracies, Wanamaker’s Globe offers

visitors an insight into what it may have been like to perform or view performances

in Shakespeare’s Globe (Fitzpatrick 432-451; Shakespeare’s Globe Trust; Gurr 27-47).

¶Locating the Globe Today

Modern-day Southwark Bridge Road runs along and partially overlaps the western side

of the original theatre site. If contemporary tourists wish to walk in the area of

the original Globe, they need only to find the intersection of Park and Southwark Bridge Roads, then

a stroll east down Park Street would take them along the northern part of the original

Globe, while alternately, heading south from the intersection would have them passing over

the western parts of the theater (Bowsher and Miller 2, 4-5, 86).

References

-

Citation

Bowsher, Julian, and Pat Miller. The Rose and the Globe—Playhouses of Shakespeare’s Bankside, Southwark: Excavations 1988–1991. London: MoLA, 2009. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Censorship.

Ed. Best, Michael. The Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/SLT/literature/publishing/censorship.html.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

DEEP: Database of Early English Playbooks. Ed. Alan B. Farmer and Zachary Lesser. http://deep.sas.upenn.edu.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Dutton, Richard, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Early Modern Theatre. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2011. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Egan, Gabriel, ed. Shakespearean London Theatres. De Montfort U and Victoria & Albert Museum. http://shalt.dmu.ac.uk/.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Fitzpatrick, Tim.From Archaeological Remains to Onion Dome: At the Upper Limits of Speculation.

Shakespeare 7.4 (2011): 432-451.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Greenfield, Jon.Design as Reconstruction/ Reconstruction as Design.

Shakespeare’s Globe Rebuilt. Ed. J.R. Mulryne and Margaret Shewring. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997. 81-96. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Gurr, Andrew.A First Doorway into the Globe.

Shakespeare Quarterly 41.1 (1990): 97-100.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Gurr, Andrew. The Shakespearean Stage 1574–1642. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1992. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Gurr, Andrew.Shakespeare’s Globe: A History of Reconstruction and Some Reasons for Trying.

Shakespeare’s Globe Rebuilt. Ed. J.R. Mulryne and Margaret Shewring. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997. 27-47. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Gurr, Andrew.The Playhouses: Archaeology And After.

Shakespeare (1745-1918) 7.4 (2011): 400-412.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Hodges, Cyril Walter. Shakespeare’s Second Globe: the Missing Monument. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1973. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Hollar, Wenceslaus. London. Antwerp: Cornelius Danckers, 1647. [See more information about this map.]This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Howard-Hill, Trevor H. Middleton’sVulgar Pasquin

: Essays on A Game at Chess. Newark: U of Delaware P, 1995. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Jonson, Ben. Ben: Ionson’s execration against Vulcan. London: J. Okes for John Benson and A. Crooke, 1640. STC 14771.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Knutson, Roslyn.Filling Fare: the Appetite for Current Issues and Traditional Forms in the Repertory of the Chamberlain’s Men.

Medieval & Renaissance Drama in England 15 (2002): 57-76.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

McCrea, Scott. The Case for Shakespeare: The End of the Authorship Question. Westport: Praeger, 2005. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

McCudden, Simon. Report on the Evaluation at Anchor Terrace Car Park, Park Street, SEI. London: Museum of London, 1989. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Mulryne, J.R. and Margaret Shewring, eds. Shakespeare’s Globe Rebuilt. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Orser, C.E., ed. Encyclopaedia of Historical Archaeology. London: Routledge, 2002. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Pignataro, Margie.Unearthing Hamlet’s Fool: A Metatheatrical Excavation Of Yorick.

Journal Of The Wooden O Symposium 6 (2006): 74-89.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Shakespeare, William. Mr. VVilliam Shakespeares comedies, histories, & tragedies Published according to the true originall copies. London, 1623. STC 22273.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Shakespeare Globe Trust.The Third Globe.

https://www.shakespearesglobe.com/discover/shakespeares-world/the-third-globe/.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Shakespeare Globe Trust.Rebuilding the Globe.

https://www.shakespearesglobe.com/discover/about-us/globe-theatre.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

The Lord Chamberlain’s Men.

Ed. Best, Michael. The Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/SLT/stage/acting/chamberlainsmen.html.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Watkins, Ronald and Jeremy Lemmon. The Poets Method. Totowa: Rowman and Littlefield, 1974. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

Cite this page

MLA citation

.

The Globe.The Map of Early Modern London, Edition 7.0, edited by , U of Victoria, 05 May 2022, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/GLOB1.htm.

Chicago citation

.

The Globe.The Map of Early Modern London, Edition 7.0. Ed. . Victoria: University of Victoria. Accessed May 05, 2022. mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/GLOB1.htm.

APA citation

. 2022. The Globe. In (Ed), The Map of Early Modern London (Edition 7.0). Victoria: University of Victoria. Retrieved from https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/editions/7.0/GLOB1.htm.

RIS file (for RefMan, RefWorks, EndNote etc.)

Provider: University of Victoria Database: The Map of Early Modern London Content: text/plain; charset="utf-8" TY - ELEC A1 - New Mexico Highlands University English 422/522 Fall 2014 Students ED - Jenstad, Janelle T1 - The Globe T2 - The Map of Early Modern London ET - 7.0 PY - 2022 DA - 2022/05/05 CY - Victoria PB - University of Victoria LA - English UR - https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/GLOB1.htm UR - https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/xml/standalone/GLOB1.xml ER -

TEI citation

<bibl type="mla"><author><name ref="#NMHU1" type="org">New Mexico Highlands University

English 422/522 Fall 2014 Students</name></author>. <title level="a">The Globe</title>.

<title level="m">The Map of Early Modern London</title>, Edition <edition>7.0</edition>,

edited by <editor><name ref="#JENS1"><forename>Janelle</forename> <surname>Jenstad</surname></name></editor>,

<publisher>U of Victoria</publisher>, <date when="2022-05-05">05 May 2022</date>,

<ref target="https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/GLOB1.htm">mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/GLOB1.htm</ref>.</bibl>

Personography

-

Amogha Lakshmi Halepuram Sridhar

ALHS

Research Assistant, 2020-present. Amogha Lakshmi Halepuram Sridhar is a fourth year student at University of Victoria, studying English and History. Her research interests include Early Modern Theatre and adaptations, decolonialist writing, and Modernist poetry.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Amogha Lakshmi Halepuram Sridhar is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Amogha Lakshmi Halepuram Sridhar is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kate LeBere

KL

Project Manager, 2020-2021. Assistant Project Manager, 2019-2020. Research Assistant, 2018-2020. Kate LeBere completed her BA (Hons.) in History and English at the University of Victoria in 2020. She published papers in The Corvette (2018), The Albatross (2019), and PLVS VLTRA (2020) and presented at the English Undergraduate Conference (2019), Qualicum History Conference (2020), and the Digital Humanities Summer Institute’s Project Management in the Humanities Conference (2021). While her primary research focus was sixteenth and seventeenth century England, she completed her honours thesis on Soviet ballet during the Russian Cultural Revolution. During her time at MoEML, Kate made significant contributions to the 1598 and 1633 editions of Stow’s Survey of London, old-spelling anthology of mayoral shows, and old-spelling library texts. She authored the MoEML’s first Project Management Manual andquickstart

guidelines for new employees and helped standardize the Personography and Bibliography. She is currently a student at the University of British Columbia’s iSchool, working on her masters in library and information science.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Kate LeBere is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Kate LeBere is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Joey Takeda

JT

Programmer, 2018-present. Junior Programmer, 2015-2017. Research Assistant, 2014-2017. Joey Takeda was a graduate student at the University of British Columbia in the Department of English (Science and Technology research stream). He completed his BA honours in English (with a minor in Women’s Studies) at the University of Victoria in 2016. His primary research interests included diasporic and indigenous Canadian and American literature, critical theory, cultural studies, and the digital humanities.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Junior Programmer

-

Markup Editor

-

Post-Conversion Editor

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Joey Takeda is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Joey Takeda is mentioned in the following documents:

Joey Takeda authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Jenstad, Janelle and Joseph Takeda.

Making the RA Matter: Pedagogy, Interface, and Practices.

Making Things and Drawing Boundaries: Experiments in the Digital Humanities. Ed. Jentery Sayers. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2018. Print.

-

-

Tye Landels-Gruenewald

TLG

Data Manager, 2015-2016. Research Assistant, 2013-2015. Tye completed his undergraduate honours degree in English at the University of Victoria in 2015.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kim McLean-Fiander

KMF

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach, 2015–2020. Associate Project Director, 2015. Assistant Project Director, 2013-2014. MoEML Research Fellow, 2013. Kim McLean-Fiander comes to The Map of Early Modern London from the Cultures of Knowledge digital humanities project at the University of Oxford, where she was the editor of Early Modern Letters Online, an open-access union catalogue and editorial interface for correspondence from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. She is currently Co-Director of a sister project to EMLO called Women’s Early Modern Letters Online (WEMLO). In the past, she held an internship with the curator of manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library, completed a doctorate at Oxford on paratext and early modern women writers, and worked a number of years for the Bodleian Libraries and as a freelance editor. She has a passion for rare books and manuscripts as social and material artifacts, and is interested in the development of digital resources that will improve access to these materials while ensuring their ongoing preservation and conservation. An avid traveler, Kim has always loved both London and maps, and so is particularly delighted to be able to bring her early modern scholarly expertise to bear on the MoEML project.Roles played in the project

-

Associate Project Director

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Managing Editor

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Research Fellow

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Kim McLean-Fiander is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Kim McLean-Fiander is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Janelle Jenstad

JJ

Janelle Jenstad is Associate Professor of English at the University of Victoria, Director of The Map of Early Modern London, and PI of Linked Early Modern Drama Online. She has taught at Queen’s University, the Summer Academy at the Stratford Festival, the University of Windsor, and the University of Victoria. With Jennifer Roberts-Smith and Mark Kaethler, she co-edited Shakespeare’s Language in Digital Media (Routledge). She has prepared a documentary edition of John Stow’s A Survey of London (1598 text) for MoEML and is currently editing The Merchant of Venice (with Stephen Wittek) and Heywood’s 2 If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody for DRE. Her articles have appeared in Digital Humanities Quarterly, Renaissance and Reformation,Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Early Modern Literary Studies, Elizabethan Theatre, Shakespeare Bulletin: A Journal of Performance Criticism, and The Silver Society Journal. Her book chapters have appeared (or will appear) in Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society (Brill, 2004), Shakespeare, Language and the Stage, The Fifth Wall: Approaches to Shakespeare from Criticism, Performance and Theatre Studies (Arden/Thomson Learning, 2005), Approaches to Teaching Othello (Modern Language Association, 2005), Performing Maternity in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2007), New Directions in the Geohumanities: Art, Text, and History at the Edge of Place (Routledge, 2011), Early Modern Studies and the Digital Turn (Iter, 2016), Teaching Early Modern English Literature from the Archives (MLA, 2015), Placing Names: Enriching and Integrating Gazetteers (Indiana, 2016), Making Things and Drawing Boundaries (Minnesota, 2017), and Rethinking Shakespeare’s Source Study: Audiences, Authors, and Digital Technologies (Routledge, 2018).Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Author (Preface)

-

Author of Preface

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Course Instructor

-

Course Supervisor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Peer Reviewer

-

Project Director

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Janelle Jenstad is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Janelle Jenstad is mentioned in the following documents:

Janelle Jenstad authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Jenstad, Janelle and Joseph Takeda.

Making the RA Matter: Pedagogy, Interface, and Practices.

Making Things and Drawing Boundaries: Experiments in the Digital Humanities. Ed. Jentery Sayers. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2018. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Building a Gazetteer for Early Modern London, 1550-1650.

Placing Names. Ed. Merrick Lex Berman, Ruth Mostern, and Humphrey Southall. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 2016. 129-145. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

The Burse and the Merchant’s Purse: Coin, Credit, and the Nation in Heywood’s 2 If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody.

The Elizabethan Theatre XV. Ed. C.E. McGee and A.L. Magnusson. Toronto: P.D. Meany, 2002. 181–202. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Early Modern Literary Studies 8.2 (2002): 5.1–26..The City Cannot Hold You

: Social Conversion in the Goldsmith’s Shop. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

The Silver Society Journal 10 (1998): 40–43.The Gouldesmythes Storehowse

: Early Evidence for Specialisation. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Lying-in Like a Countess: The Lisle Letters, the Cecil Family, and A Chaste Maid in Cheapside.

Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 34 (2004): 373–403. doi:10.1215/10829636–34–2–373. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Public Glory, Private Gilt: The Goldsmiths’ Company and the Spectacle of Punishment.

Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society. Ed. Anne Goldgar and Robert Frost. Leiden: Brill, 2004. 191–217. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Smock Secrets: Birth and Women’s Mysteries on the Early Modern Stage.

Performing Maternity in Early Modern England. Ed. Katherine Moncrief and Kathryn McPherson. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007. 87–99. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Using Early Modern Maps in Literary Studies: Views and Caveats from London.

GeoHumanities: Art, History, Text at the Edge of Place. Ed. Michael Dear, James Ketchum, Sarah Luria, and Doug Richardson. London: Routledge, 2011. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Versioning John Stow’s A Survey of London, or, What’s New in 1618 and 1633?.

Janelle Jenstad Blog. https://janellejenstad.com/2013/03/20/versioning-john-stows-a-survey-of-london-or-whats-new-in-1618-and-1633/. -

Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. Ed. Janelle Jenstad. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/MV/.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ & nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. Ed. Janelle Jenstad and the MoEML Team. MoEML. Transcribed.

-

-

Edgar Mao

EM

Edgar Yuanbo Mao received his B.A in English Language and Literature from Peking University, China, and his M.Phil in English (Literary Studies) from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is currently a D.Phil candidate in English literature (1500-1800) in the Faculty of English, University of Oxford. His doctoral research focuses on the literary and historical contexts of the Rose playhouse on the Bankside, London (1587- c.1606). His wider research interests include cultural and literary theory, early modern English drama, theatre history, and the multiple facets of the intellectual history as well as the rich material culture of the early modern period.Roles played in the project

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher (Agas Map)

-

-

Martin D. Holmes

MDH

Programmer at the University of Victoria Humanities Computing and Media Centre (HCMC). Martin ported the MOL project from its original PHP incarnation to a pure eXist database implementation in the fall of 2011. Since then, he has been lead programmer on the project and has also been responsible for maintaining the project schemas. He was a co-applicant on MoEML’s 2012 SSHRC Insight Grant.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Conceptor

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Post-Conversion Editor

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

Contributions by this author

Martin D. Holmes is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Martin D. Holmes is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Donna Woodford-Gormley

Donna Woodford-Gormley is a MoEML Pedagogical Partner. She is Professor of English at New Mexico Highlands University. She is the author of Understanding King Lear: A Student Casebook to Issues, Sources, and Historical Documents. She has also published several articles on Shakespeare and Early Modern Literature in scholarly books and journals. Currently, she is writing a book on Cuban adaptations of Shakespeare. In Fall 2014, she is teaching ENGL 422/522,Shakespeare: From the Globe to the Global,

and her students will produce an article on The Globe playhouse for MoEML.Roles played in the project

-

Guest Editor

Donna Woodford-Gormley is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Robert Armin is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Francis Beaumont is mentioned in the following documents:

Francis Beaumont authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Beaumont, Frances.

Letter from Beaumont to Ben Jonson.

The Dramatic Works of Beaumont and Fletcher. London: John Stockdale, 1811. Remediated by Hathi Trust. -

Beaumont, Francis. The Knight of the Burning Pestle. Ed. Sheldon P. Zitner. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2004. Print.

-

Richard Burbage is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Richard Brome is mentioned in the following documents:

Richard Brome authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Brome, Richard. The Demoiselle, or the New Ordinary. London: T[homas] R[oycroft] for Richard Marriot, and Thomas Dring, 1653. Remediated by Richard Brome Online.

-

Brome, Richard. A Mad Couple Well-Match’d. Five New Playes. London: Humphrey Moseley, Richard Marriot, and Thomas Dring, 1653. Sig. A5v-H2r. Remediated by Richard Brome Online.

-

Cuthbert Burbage

(b. between 1564 and 1565, d. 1636)Actor. Son of James Burbage. Brother of Richard Burbage.Cuthbert Burbage is mentioned in the following documents:

-

James Burbage is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Henry Carey

(b. 4 March 1526, d. 23 July 1596)First Baron Hunsdon. Lord Chamberlain of Elizabeth I’s household. Patron of the King’s Men. Husband of Anne Morgan. Son of William Carey. Brother of Lady Catherine Knollys.Henry Carey is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Henry Condell is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Richard Cowley is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Robert Greene is mentioned in the following documents:

Robert Greene authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Greene, Robert. The Second Part of Cony-Catching. The Elizabethan Underworld. Ed. A.V. Judges. 1930. Reprinted by New York: Octagon, 1965. 149–178. Print.

-

John Heminges

(b. in or before 1566, d. November 1630)Actor with the King’s Men. First editor of William Shakespeare’s First Folio. Artificer of mayoral shows.John Heminges is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thomas Heywood is mentioned in the following documents:

Thomas Heywood authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Heywood, Thomas. The Captives; or, The Lost Recovered. Ed. Alexander Corbin Judson. New Haven: Yale UP, 1921. Print.

-

Heywood, Thomas. The First and Second Parts of King Edward IV. Ed. Richard Rowland. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2005. The Revels Plays.

-

Heywood, Thomas. The foure prentises of London VVith the conquest of Ierusalem. As it hath bene diuerse times acted, at the Red Bull, by the Queenes Maiesties Seruants. London: [Nicholas Okes] for I. W[right], 1615. STC 13321.

-

Heywood, Thomas. The Second Part of, If you know not me, you know no bodie. VVith the building of the Royall Exchange: And the Famous Victorie of Queene Elizabeth, in the Yeare 1588. London: [Thomas Purfoot] for Nathaniell Butter, 1606. STC 13336.

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. 1998. Remediated by Project Gutenberg.

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. Ed. Vittorio Gabrieli and Giorgio Melchiori. Revels Plays. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1990. Print.

-

Thomas Heywood. Heywood’s Dramatic Works. 6 vols. Ed. W.J. Alexander. London: John Pearson, 1874. Print.

-

Wenceslaus Hollar

(b. 1607, d. 1677)Bohemian etcher. Moved to London in 1637 and etched a number of buildings and plans of the city.Wenceslaus Hollar is mentioned in the following documents:

Wenceslaus Hollar authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus. Bird’s-eye Plan of the West Central District of London. 1660. [See more information about this map.]

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus. A Generall Map of the Whole Citty of London with Westminster & All the Suburbs, by Which May Bee Computed the Proportion of That Which Is Burnt, with the Other Parts Standing. London: John Overton, 1666. [See more information about this map.]

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus. London. Antwerp: Cornelius Danckers, 1647. [See more information about this map.]

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus.

London.

Londinopolis; An Historicall Discourse or Perlustration of the City of London, the Imperial Chamber, and Chief Emporium of Great Britain: Whereunto is added another of the City of Westminster. By James Howell. London:J. Streater for Henry Twiford, George Sawbridge, Th and John Place, 1657, 1657. Insert between sig. A4v and sig. B1r. -

Hollar, Wenceslaus. A Map of Both Cities London and Westminster, Before the Fire. London, 1667. [See more information about this map.]

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus. A Map or Groundplot of the Citty of London and the Suburbes Thereof, That Is to Say, All Which Is within the Iurisdiction of the Lord Mayor or Properlie Calld’t London by Which Is Exactly Demonstrated the Present Condition Thereof, since the Last Sad Accident of Fire. The Blanke Space Signifeing the Burnt Part & Where the Houses Are Exprest, Those Places Yet Standing. London: John Overton, 1666. [See more information about this map.]

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus. A Map or Groundplott of the Citty of London, with the Suburbes Thereof so farr as the Lord Mayors Jurisdiction doeth Extend, by which is Exactly Demonstrated the Present Condition of it, since the Last Sad Accident of Fire, the Blanke Space Signifyng the Burnt Part, & where the House be those Places yet Standing. London: John Overton, 1666. [See more information about this map.]

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus. A New Map of the Citties of London Westminster & ye Borough of Southwarke with their Suburbs, Shewing ye Strets, Lanes, Allies, Courts etc. with Other Remarks, as they are now, Truly & Carefully Delineated. London: Robert Green and Robert Modern, 1675. [See more information about this map.]

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus. A New Mapp of the Cittyes of London and Westminster with the Borough of Southwark & all the Suburbs, Shewing the severall Streets, Lanes, Alleys and most of the Throwgh-faires Being a ready guide for all Strangers to find any place therein. London, 1685. [See more information about this map.]

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus. Plan of the City and Liberties of London; Shewing the Extent of the Dreadful Conflagration in the Year 1666. 1666. [See more information about this map.]

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus.

Plate 3: Extract from map by Hollar, c.1658.

St. Giles-in-the-Fields, pt 1: Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Ed. W. Edward Riley and Sir Laurence Gomme. Survey of London. Vol. 3, London: London County Council, 1912. 3. Remediated by British History Online. -

Hollar, Wenceslaus. The Prospect of London and Westminster taken from Lambeth. 1647. [See more information about this map.]

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus. A True and Exact Prospect of the Famous City of London from St. Marie Overs Steeple in Southwarke in Its Flourishing Condition before the Fire. Remediated by Folger Shakespeare Library.

-

James VI and I

James This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 6VI This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 1I King of Scotland King of England King of Ireland

(b. 1566, d. 1625)James VI and I is mentioned in the following documents:

James VI and I authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

James VI and I. Letters of King James VI and I. Ed. G.P.V. Akrigg. Berkeley: U of California P, 1984. Print.

-

Rhodes, Neill, Jennifer Richards, and Joseph Marshall, eds. King James VI and I: Selected Writings. By James VI and I. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004.

-

Ben Jonson is mentioned in the following documents:

Ben Jonson authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Chapman, George, Ben Jonson, and John Marston. Eastvvard hoe. London: George Eld for William Aspley, 1605. STC 4973.

-

Chapman, George, Ben Jonson, and John Marston. Eastward Ho! Ed. R.W. Van Fossen. New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Print.

-

Dekker, Thomas, Stephen Harrison, Ben Jonson, and Thomas Middleton. The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment of King James through the City of London, 15 March 1604, with the Arches of Triumph. Ed. R. Malcolm Smuts. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 219–279. Print.

-

Gifford, William, ed. The Works of Ben Jonson. By Ben Jonson. Vol. 1. London: Nichol, 1816. Remediated by Internet Archive.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Alchemist. London: New Mermaids, 1991. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Bartholomew Fair. Ed. E.A. Horsman. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1979. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Bartholomew Fair. Ed. Suzanne Gossett, based on The Revels Plays edition ed. E.A. Horsman. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2000. Revels Student Editions. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Ben: Ionson’s execration against Vulcan. London: J. Okes for John Benson and A. Crooke, 1640. STC 14771.

-

Jonson, Ben. B. Ion: his part of King Iames his royall and magnificent entertainement through his honorable cittie of London, Thurseday the 15. of March. 1603 so much as was presented in the first and last of their triumphall arch’s. London, 1604. STC 14756.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Complete Poetry of Ben Jonson. Ed. William B. Hunter, Jr. New York: New York UP, 1963. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Complete Poetry of Ben Jonson. Ed. William B. Hunter. Stuart Edtions. New York: New YorkUP, 1963.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Devil is an Ass. Ed. Peter Happé. Manchester and New York: Manchester UP, 1996. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Epicene. Ed. Richard Dutton. Revels Plays. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2004. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Every Man Out of His Humour. Ed. Helen Ostovich. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2001. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. The First, of Blacknesse, Personated at the Court, at White-hall, on the Twelfth Night, 1605. The Characters of Two Royall Masques: The One of Blacknesse, the Other of Beautie. Personated by the Most Magnificent of Queenes Anne Queene of Great Britaine, &c. with her Honorable Ladyes, 1605 and 1608 at White-hall. London : For Thomas Thorp, and are to be Sold at the Signe of the Tigers Head in Paules Church-yard, 1608. Sig. A3r-C2r. STC 14761.

-

Jonson, Ben. Oberon, The Faery Prince. The Workes of Benjamin Jonson. Vol. 1. London: Will Stansby, 1616. Sig. 4N2r-2N6r.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Staple of Newes. The Works. Vol. 2. London: Printed by I.B. for Robert Allot, 1631. Sig. 2A1r-2J2v.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Staple of News. Ed. Anthony Parr. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben.

To Penshurst.

The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt, Carol T. Christ, Alfred David, Barbara K. Lewalski, Lawrence Lipking, George M. Logan, Deidre Shauna Lynch, Katharine Eisaman Maus, James Noggle, Jahan Ramazani, Catherine Robson, James Simpson, Jon Stallworthy, Jack Stillinger, and M. H. Abrams. 9th ed. Vol. B. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2012. 1547. -

Jonson, Ben. Underwood. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1905. Remediated by Internet Archive.

-

Jonson, Ben. The vvorkes of Beniamin Ionson. Containing these playes, viz. 1 Bartholomew Fayre. 2 The staple of newes. 3 The Divell is an asse. London, 1641. STC 14754.

-

William Kempe is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Philip Massinger is mentioned in the following documents:

Philip Massinger authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Massinger, Philip.

The City Madam.

The Plays and Poems of Philip Massinger. Ed. Philip Edwards and Colin Gibson. Oxford: Claredon, 1976. Print. -

Massinger, Philip. A New Way to Pay Old Debts. London: Printed by E[lizabeth] P[urslowe] for Henry Seyle, 1633. STC 17639.

-

Thomas Middleton is mentioned in the following documents:

Thomas Middleton authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Bawcutt, N.W., ed.

Introduction.

The Changeling. By Thomas Middleton and William Rowley. London: Methuen, 1958. Print. -

Brissenden, Alan.

Introduction.

A Chaste Maid in Cheapside. By Thomas Middleton. 2nd ed. New Mermaids. London: A&C Black; New York: Norton, 2002. xi–xxxv. Print. -

Daalder, Joost, ed.

Introduction.

The Changeling. By Thomas Middleton and William Rowley. London: A&C Black, 1990. xii-xiii. Print. -

Dekker, Thomas, Stephen Harrison, Ben Jonson, and Thomas Middleton. The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment of King James through the City of London, 15 March 1604, with the Arches of Triumph. Ed. R. Malcolm Smuts. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 219–279. Print.

-

Holdsworth, R.V., ed.

Introduction.

A Fair Quarrel. By Thomas Middleton and William Rowley. London: Ernest Benn, 1974. xi-xxxix. Print. -

Middleton, Thomas, and Thomas Dekker. The Roaring Girl. Ed. Paul A. Mulholland. Revels Plays. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1987. Print.

-

Middleton, Thomas. A Chaste Maid in Cheapside. Ed. Alan Brissenden. 2nd ed. New Mermaids. London: Benn, 2002.

-

Middleton, Thomas. Civitatis Amor. Ed. David Bergeron. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 1202–8.

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Triumphs of Honour and Industry. London: Printed by Nicholas Okes, 1617. STC 17899.

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Triumphs of Integrity. Ed. David Bergeron. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 1766–1771.

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Triumphs of Love and Antiquity. London: Printed by Nicholas Okes, 1619. STC 17902.

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Triumphs of Truth. London, 1613. Ed. David M. Bergeron. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Clarendon, 2007. 968–976.

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Triumphs of Truth. London, 1613. STC 17903. [Differs from STC 17904 in that it does not contain the additional entertainment.]

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Triumphs of Truth. London, 1613. STC 17904. [Differs from STC 17903 in that it contains an additional entertainment celebrating Hugh Middleton’s New River project, known as the Entertainment at Amwell Head.]

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Works of Thomas Middleton, now First Collected with Some Account of the Author and notes by The Reverend Alexander Dyce. Ed. Alexander Dyce. London: E. Lumley, 1840. Print.

-

Taylor, Gary, and John Lavagnino, eds. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. By Thomas Middleton. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. The Oxford Middleton. Print.

-

Thomas Pope is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Richard III

Richard This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 3III King of England

(b. 1452, d. 1485)King of England and Lord of Ireland 1483-1485.Richard III is mentioned in the following documents:

-

William Shakespeare is mentioned in the following documents:

William Shakespeare authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. 1998. Remediated by Project Gutenberg.

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. Ed. Vittorio Gabrieli and Giorgio Melchiori. Revels Plays. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1990. Print.

-

Shakespeare, William. All’s Well That Ends Well. Ed. Helen Ostovich. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/AWW/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Antony and Cleopatra. Ed. Randall Martin. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Ant/.

-

Shakespeare, William. As You Like It. Ed. David Bevington. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/AYL/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Comedy of Errors. Ed. Matthew Steggle. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Err/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Coriolanus. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Cor/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Cymbeline. Ed. Jennifer Forsyth. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Cym/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Edward III. Ed. Jennifer Massai. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Edw/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The first part of the contention betwixt the two famous houses of Yorke and Lancaster with the death of the good Duke Humphrey: and the banishment and death of the Duke of Suffolke, and the tragicall end of the proud Cardinall of VVinchester, vvith the notable rebellion of Iacke Cade: and the Duke of Yorkes first claime vnto the crowne. London, 1594. STC 26099.

-

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. Ed. David Bevington. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Ham/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry IV, Part 1. Ed. Rosemary Gaby. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/1H4/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry IV, Part 2. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/2H4/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry V. Ed. James D. Mardock. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/H5/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry VIII. Ed. Diane Jakacki. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/H8/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry VI, Part 1. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/1H6/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry VI, Part 2. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/2H6/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry VI, Part 3. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/3H6/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Julius Caesar. Ed. John D. Cox. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/JC/.

-

Shakespeare, William. King John. Ed. Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Jn/.

-

Shakespeare, William. King Lear. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 1201–54.

-

Shakespeare, William. King Lear. Ed. Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Lr/.

-

Shakespeare, William. King Richard III. Ed. James R. Siemon. London: Methuen, 2009. The Arden Shakespeare.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Life of King Henry the Eighth. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 919–64.

-

Shakespeare, William. A Lover’s Complaint. Ed. Hardy M. Cook. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/lC/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Love’s Labor’s Lost. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/LLL/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Macbeth. Ed. Anthony Dawson. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Mac/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Measure for Measure. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 414–454.

-

Shakespeare, William. Measure for Measure. Ed. Herbert Weil. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/MM/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. Ed. Janelle Jenstad. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/MV/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Merry Wives of Windsor. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Wiv/.

-

Shakespeare, William. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Ed. Suzanne Westfall. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/MND/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Mr. VVilliam Shakespeares comedies, histories, & tragedies Published according to the true originall copies. London, 1623. STC 22273.

-

Shakespeare, William. Much Ado About Nothing. Ed. Grechen Minton. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Ado/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Othello. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Oth/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Passionate Pilgrim. Ed. Hardy M. Cook. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/PP/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Pericles. Ed. Tom Bishop. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Per/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Phoenix and the Turtle. Ed. Hardy M. Cook. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/PhT/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Rape of Lucrece. Ed. Hardy M. Cook. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Luc/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Richard II. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 740–83.

-

Shakespeare, William. Richard II. Ed. Catherine Lisak. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/R2/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Richard the Third (Modern). Ed. Adrian Kiernander. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/R3/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Romeo and Juliet. Ed. Erin Sadlack. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Rom/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Second Part of King Henry the Sixth. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 552–984.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Sonnets. Ed. Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Son/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Taming of the Shrew. Ed. Erin Kelly. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Shr/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Tempest. Ed. Brent Whitted and Paul Yachnin. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Tmp/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Timon of Athens. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Tim/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Titus Andronicus. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 966–1004.

-

Shakespeare, William. Titus Andronicus. Ed. Trey Jansen. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Tit/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Troilus and Cressida. Ed. W. L. Godshalk. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Tro/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Twelfth Night. Ed. David Carnegie and Mark Houlahan. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/TN/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Two Gentlemen of Verona. Ed. Melissa Walter. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/TGV/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Two Noble Kinsmen. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/TNK/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Venus and Adonis. Ed. Hardy M. Cook. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Ven/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Winter’s Tale. Ed. Hardin Aasand. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/WT/.

-

John Underwood is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Webster is mentioned in the following documents:

John Webster authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Dekker, Thomas, and John Webster. Vvest-vvard hoe As it hath been diuers times acted by the Children of Paules. London: [William Jaggard] for Iohn Hodgets, 1607. STC 6540.

-

Webster, John. The dramatic works of John Webster. Vol. 3. Ed. William Hazlitt. London: John Russell Smith, 1897. Print.

-

Webster, John. The Works of John Webster: An Old-Spelling Critical Edition. 3 vols. Ed. David Gunby, David Carnegie, and Macdonald P. Jackson. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2007. Print.

-

Webster, John. The Works of John Webster. Ed. Alexander Dyce. Rev. ed. London: Edward Moxon, 1857. Print.

-

George Wilkins is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Fletcher is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Ford is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Augustine Phillips is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Henry Glapthorne is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Nathan Field

Actor with the King’s Men. Playwright.Nathan Field is mentioned in the following documents:

-

William Ostler is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Nicholas Tooley is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Joseph Taylor is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Robert Benfield is mentioned in the following documents:

-

William Ecclestone is mentioned in the following documents:

-

William Sly is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Peter Streete

Carpenter.Peter Streete is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Giles Allen

Landlord of the Theatre’s plot of land.Giles Allen is mentioned in the following documents:

-

George Bryan is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Lowin is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Samuel Gilburne is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Alexander Cooke is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Richard Robinson is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Samuel Crosse

Actor with the King’s Men.Samuel Crosse is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Rice

Actor with the King’s Men.John Rice is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Schanke

Actor with the King’s Men.John Schanke is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Robert Gouge

Actor with the King’s Men.Robert Gouge is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Hamlet

Dramatic character in William Shakespeare’s Hamlet.Hamlet is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Lear

Dramatic character in William Shakespeare’s King Lear.Lear is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Othello

Dramatic character in William Shakespeare’s Othello.Othello is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Feste

Dramatic character in William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night.Feste is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Jeronimo

Dramatic character in Thomas Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy.Jeronimo is mentioned in the following documents:

Locations

-

Bankside

Described by Weinreb asredolent of squalor and vice

(Weinreb 39), London’s Bankside district in Southwark was known for its taverns, brothels and playhouses in the early modern period. However, in approximately 50 BCE its strategic location on the south bank of the Thames enticed the Roman army to use it as a military base for its conquering of Britain. From Bankside, the Romans built a bridge to the north side of the river and established the ancient town of Londinium. The Bankside district is mentioned in a variety of early modern texts, mostly in reference to the bawdy reputation of its citizens. Today, London’s Bankside is known as an arts district and is considered essential to the culture of the city.Bankside is mentioned in the following documents:

-