The Cockpit or Phoenix Playhouse

¶Location

The Cockpit, also known as the Phoenix, was an indoor commercial playhouse planned and built by the theatre entrepreneur

and actor Christopher Beeston. The title pages of plays performed at the Cockpit usually refer to its location

in Drury Lane,but G. E. Bentley offers a more precise description:

Beeston’s property lay between Drury Lane and Great Wild Street, north-west of Princes’ Street in the parish of St Giles in the Fields(Bentley vi 49). Herbert Berry adds that the playhouse was

three-eights of a mile west of the western boundary of the City of London at Temple Bar(Berry 624), and Frances Teague notes that it was

on the east side of Drury Laneand that

[t]he site was long preserved by the name of Cockpit Alley, afterwards Pitt Court(Teague 243). Bentley notes that the playhouse was nearer to Whitehall and St. James’s Palace than any other London playhouse, and was within walking distance of the Inns of Court (vi 49). He also observes that, like the Blackfriars and the Globe, the Cockpit was not far from brothels. Indoor playhouses, which were more expensive than their suburban amphitheatre equivalents, apparently benefited from the patronage of many lawyers, making the location suitable for the Cockpit. However, the Inns of Court initially provided an obstacle for Beeston when, in October 1616, the benchers of Lincoln’s Inn raised objections over the planned proximity of the theatre to their property (Berry 627). Ultimately, Beeston succeeded in opening his theatre and members of the Inns of Court are likely to have made up a sizeable part of the audience.

¶Construction

In 1616, Beeston, at the time a player with Queen Anne’s Men at the Red Bull, took a sublease on a property owned by John Best, a Grocer. That property consisted of several buildings, one of which was used for cock-fighting.

Beeston converted the cockpit into a playhouse, a process that was repeated in the next decade

when a cockpit at Whitehall was converted into a playhouse for use at court (known as the Cockpit-in-Court). Although the construction of new structures within the city was prohibited at this

time, renovation was permissible. Nonetheless, Beeston came into some difficulties: in September 1616, his bricklayer, John Shepherd, was jailed for working on a new foundation, and later that month Beeston was found to have

made a tenement Gap in transcription. Reason: Editorial omission for reasons of length or relevance. Use only in quotations in born-digital documents.[…] distant from his howserather than making

an addition to his owne dwelling howse(Bentley ii 365-6). Despite this, and despite the aforementioned objections of Lincoln’s Inn benchers, the Cockpit was opened in late winter 1616.

¶Appearance

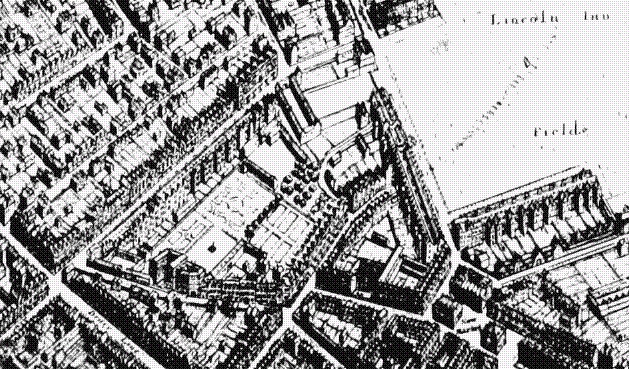

There are few facts available to reveal what the playhouse may have looked like at

any stage of its development, but there are a number of illustrations that some scholars

have conjectured are representations of the Cockpit. One such illustration is taken from the Great Map (c.1658) by Wenceslas Hollar (Plate 3, p. 3). Berry observes that

[t]he building is in the right place, and the buildings and grounds around it match those mentioned in a series of deeds and in a lawsuit of 1647 partly about the playhouse(624). If Berry is correct that the map depicts the Phoenix, then it seems that the theatre was a square building with three pitched roofs. Other illustrations have come under sustained scrutiny. John Orrell suggested that drawings now housed at Worcester College, Oxford, represent plans for Beeston’s theatre, attributing the designs to Inigo Jones and dating them to 1616 (Orrell 39-77). However, this idea is largely discounted by scholars. Teague concludes:

the drawings, splendid as they are, probably tell us nothing about the appearance of the Phoenix(244).

¶Companies

Initially, the Queen Anne’s Men played at the Cockpit, moving from the Red Bull Playhouse. The company lost its royal patronage in 1619 when the Queen died, so Beeston replaced them with Prince Charles’s Men who performed there until 1622, whereupon they returned to the Curtain. They were succeeded by the Lady Elizabeth’s Men, a company that ostensibly differed from an older troupe of the same name, famous

for provincial touring. This company was prosperous but its success was apparently

curtailed by the plague of 1625, which forced the theatres to close. When they reopened, after eight months, much

had changed: Charles had succeeded James, and the theatrical world looked very different. Beeston sought to reorganize his business by bringing in a newly formed company under the

patronage of the new Queen. The Queen Henrietta’s Men stayed at the Cockpit until 1637, far longer than any other company. Eventually, they disbanded and re-formed at a

rival theatre, Salisbury Court, but Beeston quickly formed a new troupe to take their place. This company is usually known as

Beeston’s Boys and was comprised mostly of youths supplemented by adult actors. The company continued

after Beeston’s death in 1638, until 1642, when Parliament closed all of the theatres.

¶Theatre History

¶1616 Shrove Tuesday Riots

The Cockpit suffered a considerable setback shortly after opening. On Shrove Tuesday, 4 March 1616,1 apprentices rioted and did extensive damage to the theatre (Berry 628-29). The rioting is often understood to have been motivated by theatrical concerns.

Beeston had taken his company, the Queen Anne’s Men, from the Red Bull Playhouse to the newly built Cockpit. It has been argued that the Red Bull patrons were angered by the company (and its repertory of plays) moving away from

their neighbourhood to a more expensive and exclusive venue. Mark Bayer has suggested

that the Clerkenwell community were loyal to the Red Bull and felt out of place in other social contexts (Theatre, Community 178). Furthermore, Beeston, who was suspected of unscrupulous financial and legal dealings regarding the Red Bull lease, began to fall out of favour with the local community and was even personally

attacked (Theatre, Community 205). Eleanor Collins, however, has questioned the idea that the riots were related to

the repertory. She observes that Shrove Tuesday was accumulating a general reputation

for riots, that rioting seems unlikely to have been limited to apprentices (as theatre

historians have assumed), that other buildings were also damaged, and that disturbances

were not limited to Drury Lane (132-40). Whether directly related to the theatre or not, the riots did not ultimately prevent

the playhouse from becoming successful. When it reopened three months later, it acquired

the additional name of the Phoenix, since it had risen from the ashes of the old theatre.2

¶Questions of Theatrical Taste

The transfer of the Red Bull repertory to the more expensive Cockpit playhouse raises important questions about theatrical tastes. The Red Bull had a reputation for drama that attended to citizen concerns and made extensive use

of elaborate special effects. Sometimes these plays and the playhouse audience were

denigrated as unsophisticated. The Cockpit proprietors, by contrast, were keen to establish their playhouse as urbane and elite.

Collins suggests that the transfer of bombastic plays such as Thomas Heywood’s The Rape of Lucrece from the Red Bull should alert us to continuities between ostensibly disparate playing spaces and audiences

(143). Perhaps distinctions between indoor and outdoor playhouses were less extreme than

is usually imagined. Bayer takes the argument in a different direction: he acknowledges

that the same plays were performed, apparently successfully, at both venues, but suggests

that they appealed to stratified audiences in different ways. For example, he argues

that Thomas Dekker’s Match Me in London, first performed at the Red Bull, may have appeared to its original audience as an ultimately uplifting tale of working-class

heroism, whereas a Cockpit audience may have been more inclined to have been amused at the sentimentality of

the ending (

The Curious Case67). On the other hand, Bayer claims that Philip Massinger’s A New Way to Pay Old Debts was successful at both venues because it encouraged disparate audiences to unite in condemnation of the usurer Sir Giles Overreach (Theatre, Community 195). Some evidence does support the notions that the Cockpit audience may have mocked the Red Bull and that sharp distinctions between audience responses at the two theatres existed. John Webster’s The White Devil, which was first performed at the Red Bull evidently to no great applause, was printed in 1612 with a preface that described the auditors as

ignorant asses(sig. A2r). The play was later revived at the Phoenix to a seemingly more appreciative and sophisticated audience. Similarly, Francis Beaumont’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle, a play that pokes fun at the citizen values of typical Red Bull fare, was a theatrical failure at the Blackfriars, where it was first performed by the Children of the Queen’s Revels. When it was printed, the audience was said to have failed to understand the play’s

priuy marke of Ironie(Beaumont sig. A2r). In the 1630s, however, it was revived, apparently successfully, at the Phoenix, which is perhaps an indication of this playhouse’s attempt to configure itself as sophisticated and elite, while distancing itself from the Red Bull.

It would be a mistake, however, to push this argument too far. Although the Red Bull and the Cockpit were rival venues and did not operate in partnership like the Blackfriars and Globe playhouses after 1609 when the King’s Men occupied the former, the crossover between the two theatres is striking (Collins 144). Perhaps the Phoenix audience enjoyed Beaumont’s jokes about the Red Bull, but, unlike the Blackfriars’s regulars, they also frequently watched Red Bull staples. In addition to the plays already listed, for example, A Fair Quarrel by Thomas Middleton and William Rowley was initially played at the Red Bull and revived at the Phoenix. Also, Thomas Heywood, the playwright most commonly associated with the Red Bull, had several of his plays performed at the Cockpit, including his two-part history, If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody (Gurr, Shakespearean Stage 292). Indeed, the Phoenix also housed plays generally associated with the Fortune, another outdoor theatre that, like the Red Bull, had a reputation as a plebeian playhouse. Christopher Marlowe’s Elizabethan classic, The Jew of Malta, first performed at the Rose, but also popular at the Fortune, was revived at the Cockpit in the early 1630s. Henry Chettle’s bloody revenge play The Tragedy of Hoffman, a hit in late-Elizabethan London at the Fortune, was revived in the Caroline period at the Phoenix. The Honest Whore plays, the first written by Middleton and Dekker, and the second by Dekker alone, were initially played at the Fortune in the early Jacobean period, but later revived at the Cockpit around 1635 (Gurr, Shakespearean Stage 292).

¶Elizabethan Nostalgia

These performances were part of a wider project of Elizabethan revival. Martin Butler

observes that the Phoenix

kept a high proportion of old plays in its repertoire in the 1630s(183). Indeed, the drama of Caroline England was broadly nostalgic in nature, often alluding to, or drawing upon, the established classics of the earlier theatre. John Ford, one of the most successful playwrights of the period, wrote a number of plays for the Cockpit that reimagined earlier plays in exciting new ways. ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore (1631), now firmly recognized as one of the richest jewels of Renaissance drama, reworked Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet by placing incestuous love at its centre. Perkin Warbeck (1633) gestured back towards the Elizabethan history play, but imparted its own brilliant spin on the genre. On the one hand, then, the playhouse seemed unusually prepared to revisit and celebrate older, seemingly outdated plays, including the Elizabethan Robin Hood play, George a Greene. On the other, it appeared at the forefront of dramatic invention by employing bright new talent. Ultimately, the Cockpit developed a prestigious reputation and became the principal rival of the Blackfriars, the major playhouse of the time. Although nostalgic revival was part of its appeal, the Phoenix also successfully marketed itself as an exclusive, courtly, avant-garde theatre. Ford was only one of a number of highly regarded playwrights who helped forge this reputation. Middleton and Rowley’s masterpiece, The Changeling (1622) premiered at the Phoenix. Massinger, who later went on to become the lead dramatist with the King’s Men, wrote several plays for the Cockpit, including The Renegado (1623) and The Bondman (>1623). Finally, Ben Jonson, at one time a Blackfriars regular, wrote his last fully completed play, A Tale of a Tub (1633), for the Phoenix.

¶Royal Connections

The Phoenix enjoyed particular success when Queen Henrietta’s Men became the resident company in the mid-1620s. Queen Henrietta Maria was an avid theatre lover and a regular performer in court masques, so it is perhaps

little surprise that her company received so many court performances. As Gurr notes,

by 1629 and 1630, they were playing at court almost as regularly as the King’s Men (Gurr, Shakespearian 418). During this time, they continued to perform Elizabethan hits, but they also produced

a series of plays on courtly themes. The Queen had a strong interest in Arcadianism, as demonstrated by Walter Montague’s masque The Shepherd’s Paradise, which was performed as part of the Christmas revels at Somerset House in 1633. This led the commercial company she patronized to commission similarly themed

plays for performance at the Phoenix and at court. Thomas Heywood’s Love’s Mistress (1634), which was subtitled The Queen’s Masque, was performed at the Cockpit, and also three times before the King and Queen at court. Joseph Rutter’s The Shepherd’s Holiday (1633) was likewise played at Whitehall as well as at the Phoenix. In staging these plays, the Cockpit was competing with the Blackfriars, where The King’s Men revived John Fletcher’s The Faithful Shepherdess for a Somerset House performance in 1634. Both theatres were offering their audiences a taste of a supposedly

exclusive court culture. These court connections could in turn prove lucrative to

a playwright wishing for social and professional advancement. Although several of

Heywood’s Red Bull plays were performed at the Cockpit and he also wrote The Captives (1623), The English Traveller (1624), and A Maidenhead Well Lost (1633) for the playhouse, Love’s Mistress represented his attempt at a more upmarket form of drama. Heywood would not have had this opportunity had he not been working for Queen Henrietta’s Men at the Cockpit. The case of James Shirley, effectively employed as the company’s resident writer, is also illustrative of the

Phoenix’s reputation. Shirley was commissioned to write The Triumph of Peace, a masque that was performed at the Inns of Court before the King and Queen, and he was later admitted membership of Gray’s Inn as a Valet of the Chamber of Queen Henrietta Maria in January 1634. Ultimately, he did not go on to become poet laureate, as he had hoped, but his writing

for the Cockpit unquestionably afforded him a prominent position within Caroline literary culture.

¶Reputation

The Phoenix, then, developed a prestigious reputation and became the principal rival of the Blackfriars. Indeed, in the 1630s, the Phoenix appeared on title pages even more frequently than the Blackfriars did. The growing status of the Phoenix apparently motivated its rivals to express criticism. The fact that the playhouse

shared plays, players, and playwrights with the Red Bull gave ammunition to its critics. Thus, the Cockpit was regularly denigrated as an unsophisticated theatre with a plebeian clientele.

In the early 1630s, William Davenant, a frequent contributor to the Blackfriars repertory, became involved in the promulgation of anti-Cockpit sentiment. His play, The Just Italian, which was printed in 1630, contained a dedicatory poem written by Thomas Carew that criticised the

adulterate stage(sig. A4v) of the Cockpit and the Red Bull. Davenant was responding to the fact that his own play had been poorly received at the Blackfriars, while Shirley’s The Grateful Servant was popular at the Cockpit. Similar propaganda configured the Phoenix audience as a rabble, and the Blackfriars playwrights as guardians of literary taste, wit, and judgement. Massinger, by now the principal dramatist of the King’s Men, evidently retained affection for the Cockpit (where some of his plays were still performed), and responded to the attacks by mocking the proclivities of the critics. Shirley, as the main focus of criticism, also replied aggressively. The war of words did not seem to deter theatre goers. The rivalry might even have enhanced interest in the theatre, as the 1630s were profitable years.

¶Beeston’s Boys

Queen Henrietta’s Men eventually disbanded and reformed at another rival playhouse, Salisbury Court, but Beeston quickly assembled a new company to fill their place. Beeston’s Boys, as the company became known, reprised the tradition of boy players that had emerged

in Elizabethan and Jacobean London. Their repertory is unusually well documented because

of an order issued by the Lord Chamberlain on 10 August 1639 that listed 45 plays in Beeston’s possession (Gurr, Shakespearian 424-25; see EMLoT Record 1573). The edict reveals that some plays, like Beaumont and Fletcher’s Cupid’s Revenge and Beaumont’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle, that had been written for the boy companies decades earlier, were performed by Beeston’s Boys. Cockpit classics like The Changeling and ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore also remained in the repertory, along with Shirley staples like The Traitor, The Coronation, and The Example. Other established hits performed by the boys included The Renegado, which had previously been performed at the Phoenix by both the Lady Elizabeth’s Men and Queen Henrietta’s Men. Plays like A New Way to Pay Old Debts and The Rape of Lucrece, that were associated with both the Cockpit and the Red Bull, were also performed. Among the texts listed by the Lord Chamberlain, the one known

only as The World is perhaps the most interesting. This may be a lost play (indeed, it is listed as

such on the Lost Plays Database) but it could refer to The World Tossed at Tennis, a masque, written by Middleton and Rowley and performed at an outdoor theatre, the Swan, in 1620. The masque, which alluded to contemporary political events, is highly unusual in

being performed outside of a court setting. It is fascinating to think that it may

have been revived, again, outside of the court, almost twenty years after it was written.

¶The Later Years

Christopher Beeston died in 1638 and, though this ended a distinguished career in the London theatre industry, his company continued to perform at the Phoenix. Initially, it was led by his son, William, who inherited the business, but he soon ran into difficulties. William was imprisoned in 1640 when Beeston’s Boys staged a Richard Brome play (perhaps The Court Beggar, which satirized Davenant and other courtier poets) without a license from Henry Herbert, the Master of the Revels. Ironically, Davenant, once a vocal critic of the playhouse, took on the management of Beeston’s Boys once William was imprisoned. Davenant, who had been appointed poet laureate (at Shirley’s expense) was a high profile literary figure and would, in time, become a successful

theatre proprietor, but his first stint as company manager did not last long. In 1641, he too was imprisoned, having become involved in the Army Plot (Gurr, Shakespearian 157). William Beeston, now out of Marshalsea prison, regained control of the company, and they continued to perform at the Cockpit until 1642 when all the theatres were officially closed.

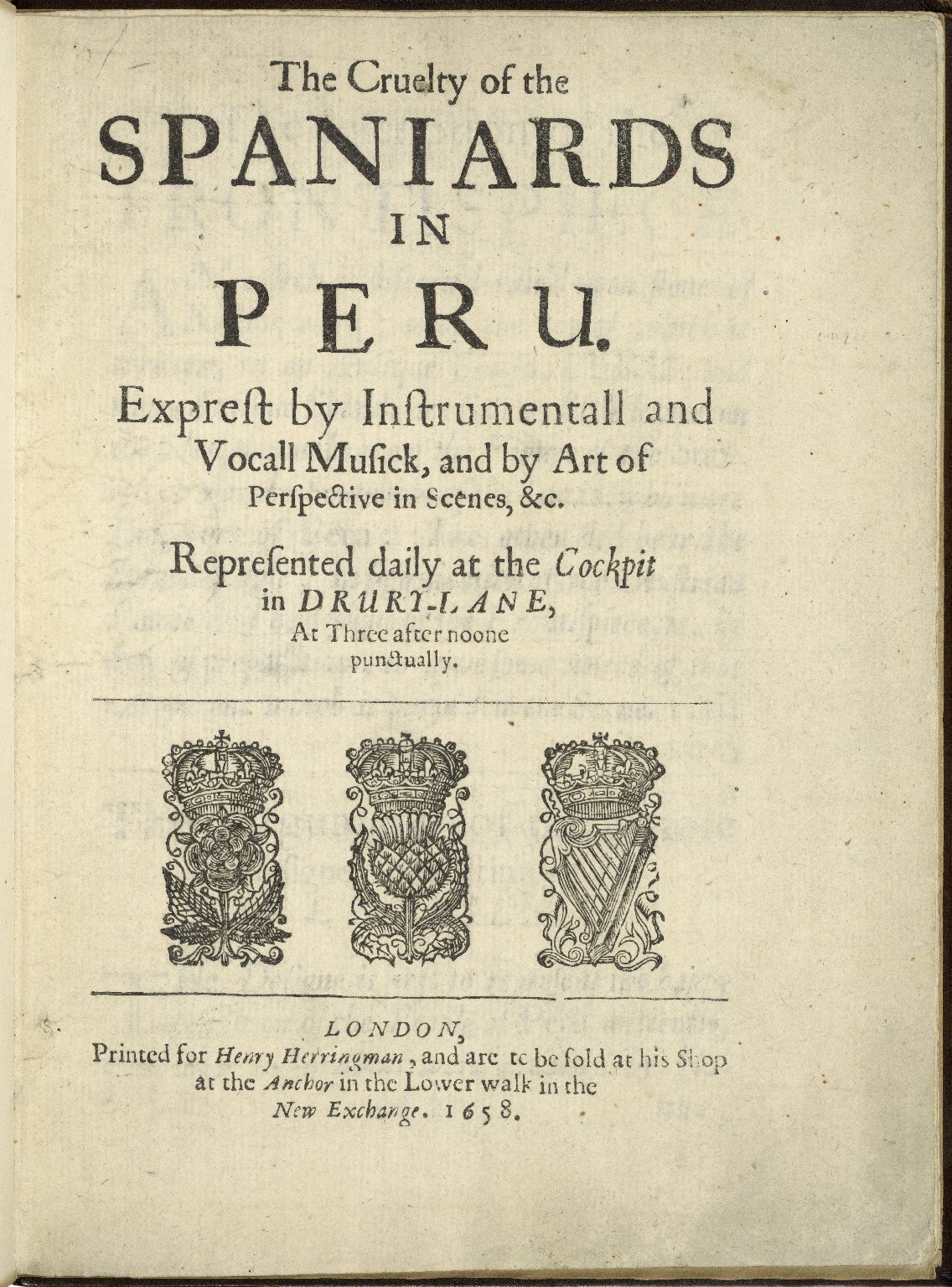

Even during the years of theatre closure, the Phoenix was, illicitly, in use. Indeed, the playhouse was raided and damaged by the authorities

on more than one occasion in an attempt to stop illegal performances (Gurr and Orrell 146). In a text printed in 1699, James Wright recalls how, after the Civil Wars, but before the theatres were reopened, some actors

banded together surreptitiously to perform Fletcher, Massinger, and Field’s Rollo, Duke of Normandy, or The Bloody Brother at the Cockpit (Wright sig. B4v-C1r). Operas, however, were apparently legal: in 1658 Davenant staged a revival of his The Siege of Rhodes (1656) at the theatre, and this was followed by The Cruelty of the Spaniards in Peru (1658) and Sir Francis Drake (1658-9). In 1660, the Phoenix officially reopened to stage plays. In October of that year, Samuel Pepys saw revivals of Shakespeare’s Othello (

The Moore of Venice), John Fletcher’s Wit Without Money and The Tamer Tamed (Teague 259; see The Diary of Samuel Pepys 11 October 1660, 16 October 1660, and 30 October 1660). However, the Phoenix, the first theatre built in London’s West End, was ultimately unable to compete with the newer, nearby Drury Lane Theatre that opened in 1663, and it soon closed.

¶Repertory

| Performance Dates3 | Title | Author | Production Date4 | Source |

| 1623, 1639 | The Bondman (The Noble Bondman) | Philip Massinger | 1624 | DEEP 718 |

| 1626, 1639 | The Wedding | James Shirley | 1629 | DEEP 742 |

| 1629, 1639 | The Grateful Servant (The Faithful Servant) | James Shirley | 1630 | DEEP 750 |

| 1624, 1630, and 1639 | The Renegado, or The Gentleman of Venice | Philip Massinger | 1630 | DEEP 752 |

| 1612, 1630 | The White Devil (Vittoria Corombona) | John Webster | 1631 | DEEP 584 |

| 1630 | Hoffman, or A Revenge for a Father | Henry Chettle | 1631 | DEEP 761 |

| 16215 | Match Me in London | Thomas Dekker | 1631 | DEEP 764 |

| 1625, 1631, and 1639 | The School of Compliment (Love Tricks) | James Shirley | 1631 | DEEP 765 |

| 1632, 1639 | The Maid of Honor | Philip Massinger | 1632 | DEEP 805 |

| 1639 | All’s Lost by Lust | William Rowley | 1633 | DEEP 807 |

| 1625, 1633, and 1639 | A New Way to Pay Old Debts | Philip Massinger | 1633 | DEEP 811 |

| 1632 | The Jew of Malta | Christopher Marlowe | 1633 | DEEP 812 |

| 1628 | The Witty Fair One | James Shirley | 1633 | DEEP 814 |

| 1631, 1639 | Love’s Sacrifice | John Ford | 1633 | DEEP 815 |

| 1633 | The Bird in a Cage (The Beauties) | James Shirley | 1633 | DEEP 816 |

| 1627 | The English Traveller | Thomas Heywood | 1633 | DEEP 821 |

| 1630, 1639 | ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore | John Ford | 1633 | DEEP 823 |

| 1632 | Perkin Warbeck | John Ford | 1634 | DEEP 833 |

| 1625-1634 | A Maidenhead Well Lost | Thomas Heywood | 1634 | DEEP 836 |

| 16356 | The Knight of the Burning Pestle | Francis Beaumont | 1635 | DEEP 605 |

| 1634 | Love’s Mistress, or The Queen’s Masque (Cupid and Psyche, or Cupid’s Mistress) | Thomas Heywood | 1636 | DEEP 849 |

| 1627, 1639 | The Great Duke of Florence | Philip Massinger | 1636 | DEEP 853 |

| 1635 | Hannibal and Scipio | Thomas Nabbes | 1637 | DEEP 863 |

| 1632 | Hyde Park | James Shirley | 1637 | DEEP 870 |

| 1635, 1639 | The Lady of Pleasure | James Shirley | 1637 | DEEP 871 |

| 1633, 1639 | The Young Admiral | James Shirley | 1637 | DEEP 872 |

| 1634, 1639 | The Example | James Shirley | 1637 | DEEP 874 |

| 1633 | The Gamester | James Shirley | 1637 | DEEP 876 |

| 1637 | 1 The Cid (The Valiant Cid) | Joseph Rutter | 1637 | DEEP 878 |

| 1623, 1639 | The Bondman (The Noble Bondman) | Philip Massinger | 1638 | DEEP 719 |

| 16357 | The Fancies Chaste and Noble | John Ford | 1638 | DEEP 883 |

| 1627-1635 | The Martyred Soldier | Henry Shirley | 1638 | DEEP 884 |

| 1636 | The Duke’s Mistress | James Shirley | 1638 | DEEP 890 |

| 16358 | The Seven Champions of Christendom | John Kirke | 1638 | DEEP 909 |

| 1632 | The Ball | James Shirley | 1639 | DEEP 911 |

| 1635 | Chabot, Admiral of France | George Chapman, James Shirley | 1639 | DEEP 912 |

| 1638 | The Lady’s Trial | John Ford | 1639 | DEEP 918 |

| 1637-1638 | Argalus and Parthenia | Henry Glapthorne | 1639 | DEEP 920 |

| 1626, 1639 | The Maid’s Revenge | James Shirley | 1639 | DEEP 930 |

| 1614 | Wit without Money | John Fletcher | 1639 | DEEP 932 |

| 1635 | The Coronation | James Shirley | 1640 | DEEP 945 |

| 1631, 1639 | Love’s Cruelty | James Shirley | 1640 | DEEP 946 |

| 16339 | The Night Walker, or The Little Thief | James Shirley, John Fletcher | 1640 | DEEP 947 |

| 1634 | The Opportunity | James Shirley | 1640 | DEEP 948 |

| 1638 | The Bride | Thomas Nabbes | 1640 | DEEP 951 |

| 1631 | The Humorous Courtier (The Duke) | James Shirley | 1640 | DEEP 952 |

| 164010 | The Arcadia | James Shirley | 1640 | DEEP 966 |

| 1637-1640 | The Ladies’ Privilege (The Lady’s Privilege) | Henry Glapthorne | 1640 | DEEP 976 |

| 163611 | Wit in a Constable | Henry Glapthorne | 1640 | DEEP 977 |

| 1636 | The Hollander | Henry Glapthorne | 1640 | DEEP 980 |

| 1632-1635 | The Prisoners | Thomas Killigrew | 1640 | DEEP 5108.01 |

| 1634-1636 | The Antiquary | Shackerley Marmion | 1641 | DEEP 987 |

| 1635-1636 | Claracilla (Claricilla) | Thomas Killigrew | 1641 | DEEP 5108.02 |

| 1641 | A Jovial Crew, or The Merry Beggars | Richard Brome | 1652 | DEEP 1062 |

| 1622, 1639 | The Changeling | Thomas Middleton, William Rowley | 1653 | DEEP 1068 |

| 1623, 1639 | The Spanish Gypsy | Thomas Dekker, John Ford, Thomas Middleton, William Rowley | 1653 | DEEP 1077 |

| 1639-1640 | The Court Beggar | Richard Brome | 1653 | DEEP 5153.03 |

| 1638 | The Cunning Lovers | Alexander Brome12 | 1654 | DEEP 1098 |

| 1615-161713 | The Poor Man’s Comfort | Robert Daborne | 1655 | DEEP 1104 |

| 1628-163414 | King John and Matilda | Robert Davenport | 1655 | DEEP 1113 |

| 1638-163915 | The Sun’s Darling | Thomas Dekker, John Ford | 1656 | DEEP 1125 |

| 1621 | The Witch of Edmonton | Thomas Dekker, William Rowley, John Ford | 1658 | DEEP 1151 |

| 165816 | The Cruelty of the Spaniards in Peru | William Davenant | 1658 | DEEP 1154 |

| 165617 | 1 The Siege of Rhodes | William Davenant | 1659 | DEEP 1121 |

| 1658-165918 | 1 Sir Francis Drake | William Davenant | 1659 | DEEP 1170 |

¶Additional Notes by MoEML Team

See also the description of the Cockpit/Phoenix and interactive walking map at Shakespearean London Theatres (ShaLT). See the Venue Record at Early Modern London Theatres (EMLoT), which includes a list of variant names as they appear in the sources and links

to primary and secondary records in their database.

Notes

- We see different dates for this event in secondary sources, depending on how the source treats historical dates. MoEML retains the Julian calendar in use in early modern England, which means that we locate this event in late 1616; see our rationale for doing so in our project. Other sources will correct the date to 1617, as it would have been had the New Year begun on 1 January. (JJ)↑

- EMLoT lists all the primary sources documenting this event. See in particular their record of Privy Council’s letter of 5 March 1616 to Lord Mayor George Bolles. (JJ)↑

- Unless specified, performance dates are taken from Gurr. According to Gurr,

the dates given for many plays are conjectural.

(JT)↑ - Production dates taken from DEEP. (JT)↑

- This date of performance comes from DEEP. Gurr gives the performance date as

1621?

and the performance location as the Red Bull. According to the title page of the 1631 printing, the playhath beene often Presented; First, at the Bull in St. IOHNS-street; And lately, at the Priuate-House in DRVRY-Lane, called the PHŒNIX

; DEEP claims that the play wasre-licensed for stage, Aug 21, 1623.

(JT)↑ - This date of performance comes from conjectural information from DEEP. For more information about Beaumont’s play, see the section on Questions of Theatrical Taste. (JT)↑

- Performance date from DEEP; it is not listed in Gurr. (JT)↑

- Performance date from DEEP; it is not listed in Gurr. (JT)↑

- Performance date from DEEP; it is not listed in Gurr. (JT)↑

- Performance date from DEEP; it is not listed in Gurr. (JT)↑

[R]evised 1639

(Gurr 298). (JT)↑- DEEP lists the author with a

(?).

(JT)↑ - Performance date from DEEP. (JT)↑

- Perhaps also performed in 1640, according to Gurr. (JT)↑

- Performance date from DEEP; it is not listed in Gurr. (JT)↑

- Performance date from DEEP; it is not listed in Gurr. (JT)↑

- Performance date from DEEP; it is not listed in Gurr. (JT)↑

- Performance date from DEEP; it is not listed in Gurr. (JT)↑

References

-

Citation

Bayer, Mark. Theatre, Community, and Civic Engagement in Jacobean London. Iowa City: U of Iowa P, 2011. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Bayer, Mark.The Curious Case of the Two Audiences: Thomas Dekker’s Match Me in London.

Imagining the Audience in Early Modern Drama, 1558–1642. Ed. Jennifer A. Low and Nova Myhill. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. 55–70. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Bentley, G.E. The Jacobean and Caroline Stage. Vol 2. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1941. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Berry, Herbert.The Phoenix.

English Professional Theatre, 1530–1660. Ed. Glynne Wickham, Herbert Berry, and William Ingram. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2000. 623–637. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Butler, Martin. Theatre and Crisis 1632–1642. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1984. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Collins, Eleanor.Repertory and Riot.

Early Theatre 13.2 (2010): 132–149. doi:10.12745/et.13.2.844.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

DEEP: Database of Early English Playbooks. Ed. Alan B. Farmer and Zachary Lesser. http://deep.sas.upenn.edu.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Egan, Gabriel, ed. Shakespearean London Theatres. De Montfort U and Victoria & Albert Museum. http://shalt.dmu.ac.uk/.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Gurr, Andrew and John Orrell. Rebuilding Shakespeare’s Globe. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1989. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Gurr, Andrew. The Shakespearian Playing Companies. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1996. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Gurr, Andrew. The Shakespearean Stage 1574–1642. 4th ed. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2009.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Hollar, Wenceslaus.Plate 3: Extract from map by Hollar, c.1658.

St. Giles-in-the-Fields, pt 1: Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Ed. W. Edward Riley and Sir Laurence Gomme. Survey of London. Vol. 3, London: London County Council, 1912. 3. Remediated by British History Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

MacLean, Sally-Beth, ed. Early Modern London Theatres. U of Toronto, King’s College of London, and U of Southampton. http://www.emlot.kcl.ac.uk/.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Orrell, John. The Theatres of Inigo Jones and John Webb. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1985. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Pepys, Samuel. The Diary of Samuel Pepys: Daily Entries from the 17th Century London Diary. Dev. Phil Gyford. https://www.pepysdiary.com/.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Teague, Frances.The Phoenix and the Cockpit-in-Court Playhouses.

The Oxford Handbook of Early Modern Theatre. Ed. Richard Dutton. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2009. 240–259. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

This item is cited in the following documents:

Cite this page

MLA citation

.

The Cockpit.The Map of Early Modern London, Edition 7.0, edited by , U of Victoria, 05 May 2022, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/COCK5.htm.

Chicago citation

.

The Cockpit.The Map of Early Modern London, Edition 7.0. Ed. . Victoria: University of Victoria. Accessed May 05, 2022. mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/COCK5.htm.

APA citation

2022. The Cockpit. In (Ed), The Map of Early Modern London (Edition 7.0). Victoria: University of Victoria. Retrieved from https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/editions/7.0/COCK5.htm.

RIS file (for RefMan, RefWorks, EndNote etc.)

Provider: University of Victoria Database: The Map of Early Modern London Content: text/plain; charset="utf-8" TY - ELEC A1 - Price, Eoin ED - Jenstad, Janelle T1 - The Cockpit T2 - The Map of Early Modern London ET - 7.0 PY - 2022 DA - 2022/05/05 CY - Victoria PB - University of Victoria LA - English UR - https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/COCK5.htm UR - https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/xml/standalone/COCK5.xml ER -

TEI citation

<bibl type="mla"><author><name ref="#PRIC1"><surname>Price</surname>, <forename>Eoin</forename></name></author>.

<title level="a">The Cockpit</title>. <title level="m">The Map of Early Modern London</title>,

Edition <edition>7.0</edition>, edited by <editor><name ref="#JENS1"><forename>Janelle</forename>

<surname>Jenstad</surname></name></editor>, <publisher>U of Victoria</publisher>,

<date when="2022-05-05">05 May 2022</date>, <ref target="https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/COCK5.htm">mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/COCK5.htm</ref>.</bibl>

Personography

-

Joey Takeda

JT

Programmer, 2018-present. Junior Programmer, 2015-2017. Research Assistant, 2014-2017. Joey Takeda was a graduate student at the University of British Columbia in the Department of English (Science and Technology research stream). He completed his BA honours in English (with a minor in Women’s Studies) at the University of Victoria in 2016. His primary research interests included diasporic and indigenous Canadian and American literature, critical theory, cultural studies, and the digital humanities.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Junior Programmer

-

Markup Editor

-

Post-Conversion Editor

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Joey Takeda is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Joey Takeda is mentioned in the following documents:

Joey Takeda authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Jenstad, Janelle and Joseph Takeda.

Making the RA Matter: Pedagogy, Interface, and Practices.

Making Things and Drawing Boundaries: Experiments in the Digital Humanities. Ed. Jentery Sayers. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2018. Print.

-

-

Tye Landels-Gruenewald

TLG

Data Manager, 2015-2016. Research Assistant, 2013-2015. Tye completed his undergraduate honours degree in English at the University of Victoria in 2015.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Sarah Milligan

SM

Research Assistant, 2012-2014. MoEML Research Affiliate. Sarah Milligan completed her MA at the University of Victoria in 2012 on the invalid persona in Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnets from the Portuguese. She has also worked with the Internet Shakespeare Editions and with Dr. Alison Chapman on the Victorian Poetry Network, compiling an index of Victorian periodical poetry.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Compiler

-

Copy Editor

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Markup Editor

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

Contributions by this author

Sarah Milligan is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Sarah Milligan is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kim McLean-Fiander

KMF

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach, 2015–2020. Associate Project Director, 2015. Assistant Project Director, 2013-2014. MoEML Research Fellow, 2013. Kim McLean-Fiander comes to The Map of Early Modern London from the Cultures of Knowledge digital humanities project at the University of Oxford, where she was the editor of Early Modern Letters Online, an open-access union catalogue and editorial interface for correspondence from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. She is currently Co-Director of a sister project to EMLO called Women’s Early Modern Letters Online (WEMLO). In the past, she held an internship with the curator of manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library, completed a doctorate at Oxford on paratext and early modern women writers, and worked a number of years for the Bodleian Libraries and as a freelance editor. She has a passion for rare books and manuscripts as social and material artifacts, and is interested in the development of digital resources that will improve access to these materials while ensuring their ongoing preservation and conservation. An avid traveler, Kim has always loved both London and maps, and so is particularly delighted to be able to bring her early modern scholarly expertise to bear on the MoEML project.Roles played in the project

-

Associate Project Director

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Managing Editor

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Research Fellow

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Kim McLean-Fiander is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Kim McLean-Fiander is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Janelle Jenstad

JJ

Janelle Jenstad is Associate Professor of English at the University of Victoria, Director of The Map of Early Modern London, and PI of Linked Early Modern Drama Online. She has taught at Queen’s University, the Summer Academy at the Stratford Festival, the University of Windsor, and the University of Victoria. With Jennifer Roberts-Smith and Mark Kaethler, she co-edited Shakespeare’s Language in Digital Media (Routledge). She has prepared a documentary edition of John Stow’s A Survey of London (1598 text) for MoEML and is currently editing The Merchant of Venice (with Stephen Wittek) and Heywood’s 2 If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody for DRE. Her articles have appeared in Digital Humanities Quarterly, Renaissance and Reformation,Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Early Modern Literary Studies, Elizabethan Theatre, Shakespeare Bulletin: A Journal of Performance Criticism, and The Silver Society Journal. Her book chapters have appeared (or will appear) in Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society (Brill, 2004), Shakespeare, Language and the Stage, The Fifth Wall: Approaches to Shakespeare from Criticism, Performance and Theatre Studies (Arden/Thomson Learning, 2005), Approaches to Teaching Othello (Modern Language Association, 2005), Performing Maternity in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2007), New Directions in the Geohumanities: Art, Text, and History at the Edge of Place (Routledge, 2011), Early Modern Studies and the Digital Turn (Iter, 2016), Teaching Early Modern English Literature from the Archives (MLA, 2015), Placing Names: Enriching and Integrating Gazetteers (Indiana, 2016), Making Things and Drawing Boundaries (Minnesota, 2017), and Rethinking Shakespeare’s Source Study: Audiences, Authors, and Digital Technologies (Routledge, 2018).Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Author (Preface)

-

Author of Preface

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Course Instructor

-

Course Supervisor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Peer Reviewer

-

Project Director

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Janelle Jenstad is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Janelle Jenstad is mentioned in the following documents:

Janelle Jenstad authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Jenstad, Janelle and Joseph Takeda.

Making the RA Matter: Pedagogy, Interface, and Practices.

Making Things and Drawing Boundaries: Experiments in the Digital Humanities. Ed. Jentery Sayers. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2018. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Building a Gazetteer for Early Modern London, 1550-1650.

Placing Names. Ed. Merrick Lex Berman, Ruth Mostern, and Humphrey Southall. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 2016. 129-145. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

The Burse and the Merchant’s Purse: Coin, Credit, and the Nation in Heywood’s 2 If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody.

The Elizabethan Theatre XV. Ed. C.E. McGee and A.L. Magnusson. Toronto: P.D. Meany, 2002. 181–202. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Early Modern Literary Studies 8.2 (2002): 5.1–26..The City Cannot Hold You

: Social Conversion in the Goldsmith’s Shop. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

The Silver Society Journal 10 (1998): 40–43.The Gouldesmythes Storehowse

: Early Evidence for Specialisation. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Lying-in Like a Countess: The Lisle Letters, the Cecil Family, and A Chaste Maid in Cheapside.

Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 34 (2004): 373–403. doi:10.1215/10829636–34–2–373. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Public Glory, Private Gilt: The Goldsmiths’ Company and the Spectacle of Punishment.

Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society. Ed. Anne Goldgar and Robert Frost. Leiden: Brill, 2004. 191–217. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Smock Secrets: Birth and Women’s Mysteries on the Early Modern Stage.

Performing Maternity in Early Modern England. Ed. Katherine Moncrief and Kathryn McPherson. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007. 87–99. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Using Early Modern Maps in Literary Studies: Views and Caveats from London.

GeoHumanities: Art, History, Text at the Edge of Place. Ed. Michael Dear, James Ketchum, Sarah Luria, and Doug Richardson. London: Routledge, 2011. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Versioning John Stow’s A Survey of London, or, What’s New in 1618 and 1633?.

Janelle Jenstad Blog. https://janellejenstad.com/2013/03/20/versioning-john-stows-a-survey-of-london-or-whats-new-in-1618-and-1633/. -

Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. Ed. Janelle Jenstad. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/MV/.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ & nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. Ed. Janelle Jenstad and the MoEML Team. MoEML. Transcribed.

-

-

Eoin Price

EP

Eoin Price is the tutor in renaissance literature at Swansea University and teaching associate at The Shakespeare Institute, University of Birmingham. His book, The Semantics of the Renaissance Stage: DefiningPublic

andPrivate

Playhouse Performance is forthcoming from Palgrave. He also has work forthcoming in Literature Compass and is a contributor to The Year’s Work in English Studies. He blogs about Renaissance drama and regularly writes for Reviewing Shakespeare.Roles played in the project

-

Author

Contributions by this author

Eoin Price is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Mark Bayer

MB

Mark Bayer is an associate professor and chair of the Department of English at the University of Texas at San Antonio. He is the author of Theatre, Community, and Civic Engagement in Jacobean England (University of Iowa Press, 2011). Mr.Bayer has also written numerous articles and book chapters on early modern literature and culture, as well as the reception of Shakespeare’s plays.Roles played in the project

-

Vetter

-

-

Martin D. Holmes

MDH

Programmer at the University of Victoria Humanities Computing and Media Centre (HCMC). Martin ported the MOL project from its original PHP incarnation to a pure eXist database implementation in the fall of 2011. Since then, he has been lead programmer on the project and has also been responsible for maintaining the project schemas. He was a co-applicant on MoEML’s 2012 SSHRC Insight Grant.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Conceptor

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Post-Conversion Editor

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

Contributions by this author

Martin D. Holmes is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Martin D. Holmes is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Francis Beaumont is mentioned in the following documents:

Francis Beaumont authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Beaumont, Frances.

Letter from Beaumont to Ben Jonson.

The Dramatic Works of Beaumont and Fletcher. London: John Stockdale, 1811. Remediated by Hathi Trust. -

Beaumont, Francis. The Knight of the Burning Pestle. Ed. Sheldon P. Zitner. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2004. Print.

-

Sir George Bolles

Sir George Bolles Sheriff Mayor

(d. 1 September 1621)Sheriff of London 1608-1609. Mayor 1617-1618. Member of the Grocers’ Company. Knighted on 31 May 1618.Sir George Bolles is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Richard Brome is mentioned in the following documents:

Richard Brome authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Brome, Richard. The Demoiselle, or the New Ordinary. London: T[homas] R[oycroft] for Richard Marriot, and Thomas Dring, 1653. Remediated by Richard Brome Online.

-

Brome, Richard. A Mad Couple Well-Match’d. Five New Playes. London: Humphrey Moseley, Richard Marriot, and Thomas Dring, 1653. Sig. A5v-H2r. Remediated by Richard Brome Online.

-

George Chapman is mentioned in the following documents:

George Chapman authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Chapman, George, Ben Jonson, and John Marston. Eastvvard hoe. London: George Eld for William Aspley, 1605. STC 4973.

-

Chapman, George, Ben Jonson, and John Marston. Eastward Ho! Ed. R.W. Van Fossen. New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Print.

-

Henry Chettle is mentioned in the following documents:

Henry Chettle authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Day, John [and Henry Chettle]. The Blind-beggar of Bednal Green. London: R. Pollard and Tho. Dring, 1659.

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. 1998. Remediated by Project Gutenberg.

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. Ed. Vittorio Gabrieli and Giorgio Melchiori. Revels Plays. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1990. Print.

-

Thomas Dekker is mentioned in the following documents:

Thomas Dekker authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Bevington, David. Introduction.

The Shoemaker’s Holiday.

By Thomas Dekker. English Renaissance Drama: A Norton Anthology. Ed. David Bevington, Lars Engle, Katharine Eisaman Maus, and Eric Rasmussen. New York: Norton, 2002. 483–487. Print. -

Dekker, Thomas, and John Webster. Vvest-vvard hoe As it hath been diuers times acted by the Children of Paules. London: [William Jaggard] for Iohn Hodgets, 1607. STC 6540.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Britannia’s Honor.

The Dramatic Works of Thomas Dekker.

Vol. 4. Ed. Fredson Bowers. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1961. Print. -

Dekker, Thomas. The Dead Tearme. Or Westminsters Complaint for long Vacations and short Termes. Written in Manner of a Dialogue betweene the two Cityes London and Westminster. 1608. The Non-Dramatic Works of Thomas Dekker. Ed. Rev. Alexander B. Grosart. 5 vols. 1885. Reprinted by New York: Russell and Russell, 1963. 1–84. Print.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The Gull’s Horn-Book: Or, Fashions to Please All Sorts of Gulls. Thomas Dekker: The Wonderful Year, The Gull’s Horn-Book, Penny-Wise, Pound-Foolish, English Villainies Discovered by Lantern and Candelight, and Selected Writings. Ed. E.D. Pendry. London: Edward Arnold, 1967. 64–109. The Stratford-upon-Avon Library 4.

-

Dekker, Thomas. If it be not good, the Diuel is in it A nevv play, as it hath bin lately acted, vvith great applause, by the Queenes Maiesties Seruants: at the Red Bull. London: Printed by Thomas Creede for John Trundle, 1612. STC 6507.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Lantern and Candlelight. 1608. Ed. Viviana Comensoli. Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2007. Publications of the Barnabe Riche Society.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Londons Tempe, or The Feild of Happines. London: Nicholas Okes, 1629. STC 6509. DEEP 736. Greg 421a. Copy: British Library; Shelfmark: C.34.g.11.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Londons Tempe, or The Feild of Happines. London: Nicholas Okes, 1629. STC 6509. DEEP 736. Greg 421a. Copy: Huntington Library; Shelfmark: Rare Books 59055.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Londons Tempe, or The Feild of Happines. London: Nicholas Okes, 1629. STC 6509. DEEP 736. Greg 421a. Copy: National Library of Scotland; Shelfmark: Bute.143.

-

Dekker, Thomas. London’s Tempe. The Dramatic Works of Thomas Dekker. Ed. Fredson Bowers. Vol. 4. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1961. Print.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The magnificent entertainment giuen to King Iames, Queene Anne his wife, and Henry Frederick the Prince, vpon the day of his Maiesties tryumphant passage (from the Tower) through his honourable citie (and chamber) of London, being the 15. of March. 1603. As well by the English as by the strangers: vvith the speeches and songes, deliuered in the seuerall pageants. London: T[homas] C[reede, Humphrey Lownes, Edward Allde and others] for Tho. Man the yonger, 1604. STC 6510

-

Dekker, Thomas. The Magnificent Entertainment: Giuen to King James, Queene Anne his wife, and Henry Frederick the Prince, ypon the day of his Majesties Triumphant Passage (from the Tower) through his Honourable Citie (and Chamber) of London being the 15. Of March. 1603. London: T. Man, 1604. Treasures in full: Renaissance Festival Books. British Library.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The owles almanacke Prognosticating many strange accidents which shall happen to this kingdome of Great Britaine this yeare, 1618. Calculated as well for the meridian mirth of London as any other part of Great Britaine. Found in an iuy-bush written in old characters, and now published in English by the painefull labours of Mr. Iocundary Merrie-braines. London: E[dward] G[riffin] for Laurence Lisle, 1618. STC 6515.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Penny-vvis[e] pound foolish or, a Bristovv diamond, set in t[wo] rings, and both crack’d Profitable for married men, pleasant for young men, a[nd a] rare example for all good women. London: A[ugustine] M[athewes] for Edward Blackmore, 1631. STC 6516.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The Second Part of the Honest Whore, with the Humors of the Patient Man, the Impatient Wife: the Honest Whore, perswaded by strong Arguments to turne Curtizan againe: her braue refuting those Arguments. London: Printed by Elizabeth All-de for Nathaniel Butter, 1630. STC 6506.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The seuen deadly sinnes of London drawne in seuen seuerall coaches, through the seuen seuerall gates of the citie bringing the plague with them. Opus septem dierum. London: E[dward] A[llde and S. Stafford] for Nathaniel Butter, 1606. STC 6522.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The Shoemaker’s Holiday. Ed. R.L. Smallwood and Stanley Wells. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1979. The Revels Plays.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The shomakers holiday. Or The gentle craft VVith the humorous life of Simon Eyre, shoomaker, and Lord Maior of London. As it was acted before the Queenes most excellent Maiestie on New-yeares day at night last, by the right honourable the Earle of Notingham, Lord high Admirall of England, his seruants. London: Valentine Sims, 1600. STC 6523.

-

Dekker, Thomas, Stephen Harrison, Ben Jonson, and Thomas Middleton. The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment of King James through the City of London, 15 March 1604, with the Arches of Triumph. Ed. R. Malcolm Smuts. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 219–279. Print.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Troia-Noua Triumphans. London: Nicholas Okes, 1612. STC 6530. DEEP 578. Greg 302a. Copy: Chapin Library; Shelfmark: 01WIL_ALMA.

-

Dekker, Thomas. TThe shoomakers holy-day. Or The gentle craft VVith the humorous life of Simon Eyre, shoomaker, and Lord Mayor of London. As it was acted before the Queenes most excellent Maiestie on New-yeares day at night last, by the right honourable the Earle of Notingham, Lord high Admirall of England, his seruants. London: G. Eld for I. Wright, 1610. STC 6524.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Westward Ho! The Dramatic Works of Thomas Dekker. Vol. 2. Ed. Fredson Bowers. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1964. Print.

-

Middleton, Thomas, and Thomas Dekker. The Roaring Girl. Ed. Paul A. Mulholland. Revels Plays. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1987. Print.

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. 1998. Remediated by Project Gutenberg.

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. Ed. Vittorio Gabrieli and Giorgio Melchiori. Revels Plays. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1990. Print.

-

Smith, Peter J.

Glossary.

The Shoemakers’ Holiday. By Thomas Dekker. London: Nick Hern, 2004. 108–110. Print.

-

Henrietta Maria

Henrietta Maria Queen consort of England Queen consort of Scotland Queen consort of Ireland

(b. 1609, d. 1669)Henrietta Maria is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Sir Henry Herbert is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thomas Heywood is mentioned in the following documents:

Thomas Heywood authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Heywood, Thomas. The Captives; or, The Lost Recovered. Ed. Alexander Corbin Judson. New Haven: Yale UP, 1921. Print.

-

Heywood, Thomas. The First and Second Parts of King Edward IV. Ed. Richard Rowland. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2005. The Revels Plays.

-

Heywood, Thomas. The foure prentises of London VVith the conquest of Ierusalem. As it hath bene diuerse times acted, at the Red Bull, by the Queenes Maiesties Seruants. London: [Nicholas Okes] for I. W[right], 1615. STC 13321.

-

Heywood, Thomas. The Second Part of, If you know not me, you know no bodie. VVith the building of the Royall Exchange: And the Famous Victorie of Queene Elizabeth, in the Yeare 1588. London: [Thomas Purfoot] for Nathaniell Butter, 1606. STC 13336.

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. 1998. Remediated by Project Gutenberg.

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. Ed. Vittorio Gabrieli and Giorgio Melchiori. Revels Plays. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1990. Print.

-

Thomas Heywood. Heywood’s Dramatic Works. 6 vols. Ed. W.J. Alexander. London: John Pearson, 1874. Print.

-

Wenceslaus Hollar

(b. 1607, d. 1677)Bohemian etcher. Moved to London in 1637 and etched a number of buildings and plans of the city.Wenceslaus Hollar is mentioned in the following documents:

Wenceslaus Hollar authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus. Bird’s-eye Plan of the West Central District of London. 1660. [See more information about this map.]

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus. A Generall Map of the Whole Citty of London with Westminster & All the Suburbs, by Which May Bee Computed the Proportion of That Which Is Burnt, with the Other Parts Standing. London: John Overton, 1666. [See more information about this map.]

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus. London. Antwerp: Cornelius Danckers, 1647. [See more information about this map.]

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus.

London.

Londinopolis; An Historicall Discourse or Perlustration of the City of London, the Imperial Chamber, and Chief Emporium of Great Britain: Whereunto is added another of the City of Westminster. By James Howell. London:J. Streater for Henry Twiford, George Sawbridge, Th and John Place, 1657, 1657. Insert between sig. A4v and sig. B1r. -

Hollar, Wenceslaus. A Map of Both Cities London and Westminster, Before the Fire. London, 1667. [See more information about this map.]

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus. A Map or Groundplot of the Citty of London and the Suburbes Thereof, That Is to Say, All Which Is within the Iurisdiction of the Lord Mayor or Properlie Calld’t London by Which Is Exactly Demonstrated the Present Condition Thereof, since the Last Sad Accident of Fire. The Blanke Space Signifeing the Burnt Part & Where the Houses Are Exprest, Those Places Yet Standing. London: John Overton, 1666. [See more information about this map.]

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus. A Map or Groundplott of the Citty of London, with the Suburbes Thereof so farr as the Lord Mayors Jurisdiction doeth Extend, by which is Exactly Demonstrated the Present Condition of it, since the Last Sad Accident of Fire, the Blanke Space Signifyng the Burnt Part, & where the House be those Places yet Standing. London: John Overton, 1666. [See more information about this map.]

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus. A New Map of the Citties of London Westminster & ye Borough of Southwarke with their Suburbs, Shewing ye Strets, Lanes, Allies, Courts etc. with Other Remarks, as they are now, Truly & Carefully Delineated. London: Robert Green and Robert Modern, 1675. [See more information about this map.]

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus. A New Mapp of the Cittyes of London and Westminster with the Borough of Southwark & all the Suburbs, Shewing the severall Streets, Lanes, Alleys and most of the Throwgh-faires Being a ready guide for all Strangers to find any place therein. London, 1685. [See more information about this map.]

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus. Plan of the City and Liberties of London; Shewing the Extent of the Dreadful Conflagration in the Year 1666. 1666. [See more information about this map.]

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus.

Plate 3: Extract from map by Hollar, c.1658.

St. Giles-in-the-Fields, pt 1: Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Ed. W. Edward Riley and Sir Laurence Gomme. Survey of London. Vol. 3, London: London County Council, 1912. 3. Remediated by British History Online. -

Hollar, Wenceslaus. The Prospect of London and Westminster taken from Lambeth. 1647. [See more information about this map.]

-

Hollar, Wenceslaus. A True and Exact Prospect of the Famous City of London from St. Marie Overs Steeple in Southwarke in Its Flourishing Condition before the Fire. Remediated by Folger Shakespeare Library.

-

James VI and I

James This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 6VI This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 1I King of Scotland King of England King of Ireland

(b. 1566, d. 1625)James VI and I is mentioned in the following documents:

James VI and I authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

James VI and I. Letters of King James VI and I. Ed. G.P.V. Akrigg. Berkeley: U of California P, 1984. Print.

-

Rhodes, Neill, Jennifer Richards, and Joseph Marshall, eds. King James VI and I: Selected Writings. By James VI and I. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004.

-

Inigo Jones is mentioned in the following documents:

Inigo Jones authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Jones, Inigo.

Design for the new

1610s. RIBA 12957.Italyan

gate, Arundel House, Strand, London.

-

Ben Jonson is mentioned in the following documents:

Ben Jonson authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Chapman, George, Ben Jonson, and John Marston. Eastvvard hoe. London: George Eld for William Aspley, 1605. STC 4973.

-

Chapman, George, Ben Jonson, and John Marston. Eastward Ho! Ed. R.W. Van Fossen. New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Print.

-

Dekker, Thomas, Stephen Harrison, Ben Jonson, and Thomas Middleton. The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment of King James through the City of London, 15 March 1604, with the Arches of Triumph. Ed. R. Malcolm Smuts. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 219–279. Print.

-

Gifford, William, ed. The Works of Ben Jonson. By Ben Jonson. Vol. 1. London: Nichol, 1816. Remediated by Internet Archive.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Alchemist. London: New Mermaids, 1991. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Bartholomew Fair. Ed. E.A. Horsman. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1979. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Bartholomew Fair. Ed. Suzanne Gossett, based on The Revels Plays edition ed. E.A. Horsman. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2000. Revels Student Editions. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Ben: Ionson’s execration against Vulcan. London: J. Okes for John Benson and A. Crooke, 1640. STC 14771.

-

Jonson, Ben. B. Ion: his part of King Iames his royall and magnificent entertainement through his honorable cittie of London, Thurseday the 15. of March. 1603 so much as was presented in the first and last of their triumphall arch’s. London, 1604. STC 14756.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Complete Poetry of Ben Jonson. Ed. William B. Hunter, Jr. New York: New York UP, 1963. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Complete Poetry of Ben Jonson. Ed. William B. Hunter. Stuart Edtions. New York: New YorkUP, 1963.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Devil is an Ass. Ed. Peter Happé. Manchester and New York: Manchester UP, 1996. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Epicene. Ed. Richard Dutton. Revels Plays. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2004. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Every Man Out of His Humour. Ed. Helen Ostovich. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2001. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. The First, of Blacknesse, Personated at the Court, at White-hall, on the Twelfth Night, 1605. The Characters of Two Royall Masques: The One of Blacknesse, the Other of Beautie. Personated by the Most Magnificent of Queenes Anne Queene of Great Britaine, &c. with her Honorable Ladyes, 1605 and 1608 at White-hall. London : For Thomas Thorp, and are to be Sold at the Signe of the Tigers Head in Paules Church-yard, 1608. Sig. A3r-C2r. STC 14761.

-

Jonson, Ben. Oberon, The Faery Prince. The Workes of Benjamin Jonson. Vol. 1. London: Will Stansby, 1616. Sig. 4N2r-2N6r.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Staple of Newes. The Works. Vol. 2. London: Printed by I.B. for Robert Allot, 1631. Sig. 2A1r-2J2v.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Staple of News. Ed. Anthony Parr. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben.

To Penshurst.

The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt, Carol T. Christ, Alfred David, Barbara K. Lewalski, Lawrence Lipking, George M. Logan, Deidre Shauna Lynch, Katharine Eisaman Maus, James Noggle, Jahan Ramazani, Catherine Robson, James Simpson, Jon Stallworthy, Jack Stillinger, and M. H. Abrams. 9th ed. Vol. B. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2012. 1547. -

Jonson, Ben. Underwood. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1905. Remediated by Internet Archive.

-

Jonson, Ben. The vvorkes of Beniamin Ionson. Containing these playes, viz. 1 Bartholomew Fayre. 2 The staple of newes. 3 The Divell is an asse. London, 1641. STC 14754.

-

Christopher Marlowe is mentioned in the following documents:

Christopher Marlowe authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Marlowe, Christopher. The Troublesome Raigne and Lamentable Death of Edward the Second, King of England. London: William Jones, dwelling neere Holbourne conduit, at the signe of the Gunne, 1594.

-

Philip Massinger is mentioned in the following documents:

Philip Massinger authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Massinger, Philip.

The City Madam.

The Plays and Poems of Philip Massinger. Ed. Philip Edwards and Colin Gibson. Oxford: Claredon, 1976. Print. -

Massinger, Philip. A New Way to Pay Old Debts. London: Printed by E[lizabeth] P[urslowe] for Henry Seyle, 1633. STC 17639.

-

Thomas Middleton is mentioned in the following documents:

Thomas Middleton authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Bawcutt, N.W., ed.

Introduction.

The Changeling. By Thomas Middleton and William Rowley. London: Methuen, 1958. Print. -

Brissenden, Alan.

Introduction.

A Chaste Maid in Cheapside. By Thomas Middleton. 2nd ed. New Mermaids. London: A&C Black; New York: Norton, 2002. xi–xxxv. Print. -

Daalder, Joost, ed.

Introduction.

The Changeling. By Thomas Middleton and William Rowley. London: A&C Black, 1990. xii-xiii. Print. -

Dekker, Thomas, Stephen Harrison, Ben Jonson, and Thomas Middleton. The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment of King James through the City of London, 15 March 1604, with the Arches of Triumph. Ed. R. Malcolm Smuts. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 219–279. Print.

-

Holdsworth, R.V., ed.

Introduction.

A Fair Quarrel. By Thomas Middleton and William Rowley. London: Ernest Benn, 1974. xi-xxxix. Print. -

Middleton, Thomas, and Thomas Dekker. The Roaring Girl. Ed. Paul A. Mulholland. Revels Plays. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1987. Print.

-

Middleton, Thomas. A Chaste Maid in Cheapside. Ed. Alan Brissenden. 2nd ed. New Mermaids. London: Benn, 2002.

-

Middleton, Thomas. Civitatis Amor. Ed. David Bergeron. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 1202–8.

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Triumphs of Honour and Industry. London: Printed by Nicholas Okes, 1617. STC 17899.

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Triumphs of Integrity. Ed. David Bergeron. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 1766–1771.

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Triumphs of Love and Antiquity. London: Printed by Nicholas Okes, 1619. STC 17902.

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Triumphs of Truth. London, 1613. Ed. David M. Bergeron. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Clarendon, 2007. 968–976.

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Triumphs of Truth. London, 1613. STC 17903. [Differs from STC 17904 in that it does not contain the additional entertainment.]

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Triumphs of Truth. London, 1613. STC 17904. [Differs from STC 17903 in that it contains an additional entertainment celebrating Hugh Middleton’s New River project, known as the Entertainment at Amwell Head.]

-

Middleton, Thomas. The Works of Thomas Middleton, now First Collected with Some Account of the Author and notes by The Reverend Alexander Dyce. Ed. Alexander Dyce. London: E. Lumley, 1840. Print.

-

Taylor, Gary, and John Lavagnino, eds. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. By Thomas Middleton. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. The Oxford Middleton. Print.

-

Walter Montague

Walter Montague David Cutler

(b. 1604, d. 1677)Courtier, secret agent, and Abbot of St. Martin’s. Author of The Shepherd’s Paradise.Walter Montague is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Samuel Pepys is mentioned in the following documents:

Samuel Pepys authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Pepys, Samuel. The Diary of Samuel Pepys: A New and Complete Transcription. Ed. Robert Latham and William Matthews. 11 vols. Berkeley : U of California P, 1970–1983.

-

Pepys, Samuel. The Diary of Samuel Pepys: Daily Entries from the 17th Century London Diary. Dev. Phil Gyford. https://www.pepysdiary.com/.

-

Pepys, Samuel. Diary of Samuel Pepys. Remediated by Project Gutenberg.

-

Joseph Rutter is mentioned in the following documents:

-

William Shakespeare is mentioned in the following documents:

William Shakespeare authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. 1998. Remediated by Project Gutenberg.

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. Ed. Vittorio Gabrieli and Giorgio Melchiori. Revels Plays. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1990. Print.

-

Shakespeare, William. All’s Well That Ends Well. Ed. Helen Ostovich. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/AWW/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Antony and Cleopatra. Ed. Randall Martin. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Ant/.

-

Shakespeare, William. As You Like It. Ed. David Bevington. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/AYL/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Comedy of Errors. Ed. Matthew Steggle. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Err/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Coriolanus. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Cor/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Cymbeline. Ed. Jennifer Forsyth. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Cym/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Edward III. Ed. Jennifer Massai. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Edw/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The first part of the contention betwixt the two famous houses of Yorke and Lancaster with the death of the good Duke Humphrey: and the banishment and death of the Duke of Suffolke, and the tragicall end of the proud Cardinall of VVinchester, vvith the notable rebellion of Iacke Cade: and the Duke of Yorkes first claime vnto the crowne. London, 1594. STC 26099.

-

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. Ed. David Bevington. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Ham/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry IV, Part 1. Ed. Rosemary Gaby. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/1H4/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry IV, Part 2. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/2H4/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry V. Ed. James D. Mardock. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/H5/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry VIII. Ed. Diane Jakacki. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/H8/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry VI, Part 1. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/1H6/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry VI, Part 2. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/2H6/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry VI, Part 3. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/3H6/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Julius Caesar. Ed. John D. Cox. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/JC/.

-

Shakespeare, William. King John. Ed. Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Jn/.

-

Shakespeare, William. King Lear. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 1201–54.

-

Shakespeare, William. King Lear. Ed. Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Lr/.

-

Shakespeare, William. King Richard III. Ed. James R. Siemon. London: Methuen, 2009. The Arden Shakespeare.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Life of King Henry the Eighth. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 919–64.

-

Shakespeare, William. A Lover’s Complaint. Ed. Hardy M. Cook. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/lC/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Love’s Labor’s Lost. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/LLL/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Macbeth. Ed. Anthony Dawson. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Mac/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Measure for Measure. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 414–454.

-

Shakespeare, William. Measure for Measure. Ed. Herbert Weil. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/MM/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. Ed. Janelle Jenstad. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/MV/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Merry Wives of Windsor. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Wiv/.

-

Shakespeare, William. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Ed. Suzanne Westfall. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/MND/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Mr. VVilliam Shakespeares comedies, histories, & tragedies Published according to the true originall copies. London, 1623. STC 22273.

-

Shakespeare, William. Much Ado About Nothing. Ed. Grechen Minton. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Ado/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Othello. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Oth/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Passionate Pilgrim. Ed. Hardy M. Cook. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/PP/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Pericles. Ed. Tom Bishop. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Per/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Phoenix and the Turtle. Ed. Hardy M. Cook. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/PhT/.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Rape of Lucrece. Ed. Hardy M. Cook. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Luc/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Richard II. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 740–83.

-

Shakespeare, William. Richard II. Ed. Catherine Lisak. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/R2/.

-

Shakespeare, William. Richard the Third (Modern). Ed. Adrian Kiernander. Internet Shakespeare Editions. U of Victoria. http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/R3/.

-