Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (or Anna, as she referred to herself and signed her correspondence) was the wife of King James VI and I. She was also, and significantly so with respect to assessing the depth of her political

networks, the sister of a king (Christian IV), the daughter of a king (Frederick II), the sister of women who all married high-ranking rulers and administrators within

the Holy Roman Empire, and the mother of a king and of a queen (Charles I and Elizabeth of Bohemia, respectively). Anne’s prominent familial connections were significant, and her brothers later visited

her in England (Ulric, Bishop of Schwerin and Schleswig, in 1604-1605, and Christian IV, King of Denmark, in 1606 and again in 1612).1 Anne was an important cultural patron at both the Scottish and English courts, employing

talents like Ben Jonson and Inigo Jones to stage court masques and other entertainments as well as serving as a patron of

the arts and establishing a circle of like-minded individuals around her. As queen

consort she was also active in politics. Many earlier studies of her life, biographies

of her husband, and political histories of the period tend to perpetuate an image

of Anne as frivolous and peripheral to Jacobean politics. As Leeds Barroll puts it, there

has been

a strongly-entrenched scholarly tradition of Anne as shallow, vain, and addicted to ludicrously frivolous activities(Barroll,

Theatre as Text178-79). This view has been importantly re-evaluated in recent years and Anne’s political contributions have come to be better assessed.2

Anne was born 12 December 1574 at Skanderborg Castle. She was the second daughter (of six children) of King Frederick II of Denmark and his wife Sophia. Her younger brother later reigned as Christian IV and her sisters all married other Northern European rulers. Anne spent her formative years with her grandparents and was taught to write in an elegant

italic hand in both Danish and German. Later she learned French, Scots, and English

(and also employed an Italian tutor). As a child, Anne was exposed to the pageantry of the powerful and sophisticated early modern Danish

court, the beginning of a life-long appreciation of the arts. Many members of her

immediate family earned reputations for cultural sophistication. When Anne is viewed alongside them, Mara Wade argues, her artistic leanings take on a new significance

(Wade 49-80).

In the 1580s, negotiations for a Danish-Scots marriage began. Anne and James were married by proxy in 1589. When Anne’s journey to Scotland was delayed after severe storms forced her to land in Norway,

James travelled to collect his bride and the pair arrived in Scotland on 1 May 1590. During their sojourn in Denmark (from 1589 to 1590), the pair engaged in various intellectual and politically significant activities,

including visiting Tycho Brahe’s observatory and celebrating the marriage of Anne’s sister Elizabeth to Heinrich Julius, Duke of Branuscweig-Wolfenbüttel and a prominent servant of Emperor Rudolf II. The marriage of Anne and James was not the failure that some have alleged. Some scholars have regarded James, with his penchant for male favourites, as driven by homoerotic desires.3 This perspective has led some of those scholars, such as Lewalski, to postulate that

James’s sexual preferences resulted in Anne’s marginalization in both public and private as her husband lavished favour and accorded

influence to a series of male favourites (Lewalski 4). J.W. Williamson alleged that Anne was little more than

the indignant and frequently hysterical victim of the King’s anti-female policy(Williamson 15). James certainly preferred the company of his male friends and may well have engaged in sexual liaisons with some of them (although this did not prevent him from fathering children with Anne and being rumoured to have kept Lady Anne Murray as a mistress between 1593-1595) (Rhodes, Richards, and Marshall 129-31). However, the relationship between Anne and James was certainly successful in terms of the production of heirs and was not necessarily an emotionally unsatisfying one either. Their correspondence suggests a certain intimacy and companionate bond; James also involved Anne in his relationships with his male companions by asking for her approval before any of them were elevated to positions of influence within his service (Cuddy 195).4

Anne was involved in the factional politics of the Scottish court, engaging in several

attempts to undermine several political rivals. It was also at the Scottish court

that she first displayed the enthusiasm for state theatre and court ritual that would

come to be seen as the defining feature of her career as a queen consort. While in

Scotland, Anne bore several children: Henry (b. 1594, d. 1612), Elizabeth (b. 1596, d. 1662), Margaret (b, 1598, d. 1600), Charles (b. 1600, d. 1649), and Robert (b. 1602, d. 1602). Later, in England, she bore two more: Mary (b. 1605, d. 1607) and Sophia (born and died in 1606). Only Henry, Elizabeth, and Charles survived infancy (Henry died in 1612, to Anne’s great devastation, while Charles succeeded his father, and Elizabeth married Frederick V, Elector Palatinate).5 While in Scotland, Anne likely converted to Catholicism and it is probable that James knew of it and allowed her to quietly practice her faith.

On 24 March 1603, the unmarried Elizabeth I died. In the absence of a direct heir, James was proclaimed king by virtue of his blood ties to the Tudor dynasty through his

mother Mary Queen of Scots and his father Henry Darnley. Anne and James were crowned together on 25 July 1603 at Westminster Abbey. The ceremony had been postponed due to an outbreak of plague raging in London. When it did occur, the coronation lacked the customary brilliance because of the

ravages of the plague.6 Perhaps the most noteworthy aspect of the crowning of the new King and Queen was

Anne’s refusal during the service to accept the Anglican communion offered to her by the

Archbishop of Canterbury.7 The somewhat lacklustre spectacle of James and Anne’s joint coronation was countered the following year with the City of London’s staging of the official opening of Parliament accompanied by a grand civic pageant.8

Once in England, Anne continued her pursuit of cultural display. She developed an extensive art collection,

patronized Inigo Jones, and had him design the Queen’s House at Greenwich and refurbish Oatlands Palace for her use. She befriended other prominent cultural

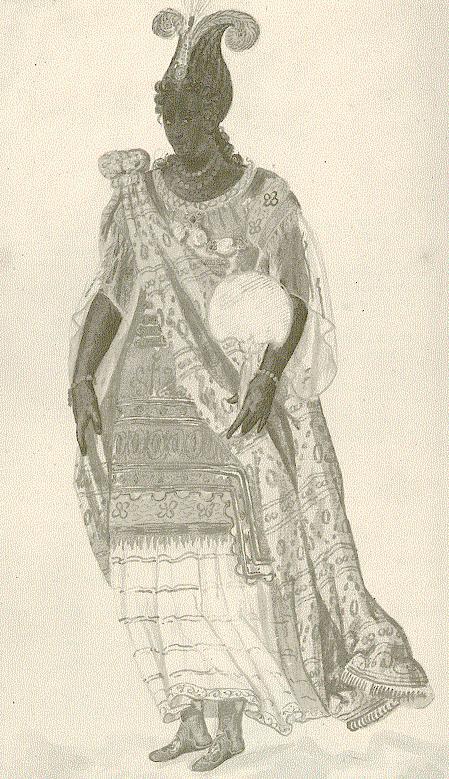

patrons such as Lucy Russell, Countess of Bedford. She established herself at London’s Somerset House, which she renamed Denmark House, and immersed herself in a cosmopolitan lifestyle. Anne set the tone for court fashion, insisting, for example, that the wheel-shaped farthingale

be worn at court long after it had gone out of fashion elsewhere (Reynolds 42).9 In Scotland she had appointed the Edinburgh jeweller George Heriot as her goldsmith for life. He followed her to England in 1603, establishing himself in a town house on the Strand. She was a great patron of artists, and it is estimated that

there are more oil paintings of Anne of Denmark than of any previous English queen consort. Queen Anne was the first great royal patroness of art in England(Pugh 173). She was, likewise, a notable book collector.

Anne firmly established herself as a key source of cultural patronage through her high-profile

involvement with court masques. Masquing was an underdeveloped theatrical form in

England in 1603. Masques (

disguisings) had been popular at the English court during the early years of the reign of Henry VIII, but had not evolved to the same degree as in other European courts. Influenced by Italian tastes, they were a complex artistic form, danced rather than acted, featuring lavish costumes and set designs, and incorporating mythological themes. Anne elevated the English masque to an equal footing with the glittering performances enacted on the Continent. Some masques, such as the Masque of Blackness and Vision of the Twelve Goddesses, drew criticism for their risqué costuming and stage direction. Dudley Carleton, for example, described the costuming used in the Masque of Blackness as

too light and courtesan like(Carleton 55). Yet many of the productions won Anne great acclaim. Zorzi Guistinian, a Venetian ambassador at James’s court, described in a dispatch

the splendour of the spectacle, which was worthy of her Majesty’s greatness. So well composed and ordered was it all that it is evident the mind of her Majesty, the authoress of the whole, is gifted no less highly than her person. She reaped universal applause(Giustinian 86). While some historians have looked at Anne’s masquing derisively as extravagant and vacuous, many contemporaries saw masques as an important facet of court display that showcased the sophistication of the English court to foreign observers and domestic notables.10 Masques also resulted in unique artistic pfroducts that harnessed the talents of individuals such as Jonson and Jones.

While many of the masques staged by Anne offered political commentaries, she was also directly involved with politics (although

many earlier scholars mistakenly regarded her political influence as negligible).

She intervened with her husband on behalf of many people including Sir Walter Raleigh and Lady Anne Clifford and was seen as a valuable ally.11 Anne likewise served on the Council of Regency established by James in 1617 to govern England while he visited Scotland. While James was away, courtiers flocked to Anne and

the political centre of England shifted to Anne’s palace at Greenwich(Roper 51). She also expressed her political preferences in less overt ways, such as snubbing ambassadors and negotiating marriages for her children that reflected her allegiances. Anne was involved in factional politics. James was powerfully influenced by favourites and early in his English reign he became attached to Robert Carr, whom he made Earl of Somerset and entrusted with political responsibilities (including the post of Secretary in 1612) to which he was quite unsuited. Carr’s influence over James inspired a good deal of animosity, as favourites typically did in the period. Carr’s alignment with the Howard faction through a marriage to Frances Howard caused a scandal because she was married to the Earl of Essex12 when she began her liaison with Carr and dubiously accused her husband of impotency in order to secure an annulment, which James commanded the clerics to grant. When Carr began delegating his responsibilities to his more competent friend, Thomas Overbury, Anne was mobilized into action and became a vocal opponent. She felt that Carr and Overbury were overly proud, and she opposed the political aims of the Howard faction. She allied herself with other enemies of Carr and eventually replaced him with George Villiers and convinced James to commit Overbury to the Tower of London for his perceived insolence. As a later commentator noted (and the assertion is supported in other, more contemporary sources), Carr was

not very acceptable to the Queen,and

she became the head of a great Faction against him(Wilson sig. L4r).

Anne died on 2 March 1619 and was buried in Westminster Abbey. As a woman, Anne was denied access to the official channels of political power. However, like other

queens consort, she wielded influence on an informal level. Using mechanisms such

as the language of cultural display (an until recently undervalued aspect of her career

as queen consort) and patronage, alongside more direct political involvement, she

pursued her agenda and played an important role in the factional politics that were

so prominent a part of the early modern court. She likewise played a key role in the

artistic and cultural development of fashionable London society.

Notes

- While visiting their sister, both Ulric and Christian engaged their sister and her spouse with respect to political matters. For example, Ulric staged a masque with political undertones and also urged renewal of the war with Spain (see Lemon and Green). (CET)↑

- See Barroll, Anne of Denmark, Queen of England. (CET)↑

- See, for example, Bergeron, King James and Letters of Homoerotic Desire, Goldberg,

James I and the Theatre of Conscience,

Goldberg, James I and the Politics of Literature, Lewalski, and Stone, esp. 89. The manner in which James’s alleged sexual preferences intersect with the political history of the period and notions of masculinity, effeminacy, and deviance have been addressed by Young and Shephard. (CET)↑ - For examples of the couple’s letters, see edited collections by Akrigg and Walker and MacDonald. (CET)↑

- On the elaborate celebrations of this union, see Nichols, vol. 3 536-53 (CET)↑

- For a full account of the English coronation, see Nichols, vol. 1 228-34. See also Williams 84-85. (CET)↑

- John Whitgift, archbishop of Canterbury, 1583-1604. (TLG)↑

- See Bergeron,

King James’s Civic Pageant and Parliamentary Speech in March 1604.

(CET)↑ - See also Fields. (CET)↑

- See Parry,

The Politics of the Jacobean Masque

and Parry, The Golden Age Restor’d: The Culture of the Stuart Court, 1603-1642. (CET)↑ - Examples of this can be found in the diaries of Anne Clifford (Clifford) as well as in letters from Raleigh to Anne (Lemon and Green). (CET)↑

- Robert Devereux, third earl of Essex. (TLG)↑

References

-

Citation

Barroll, Leeds.Theatre as Text: The Case of Queen Anna and the Jacobean Court Masque.

The Elizabethan Theatre 14 (1991): 175–193.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Barroll, Leeds. Anna of Denmark, Queen of England: A Cultural Biography. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 2001. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Bergeron, David M. King James and Letters of Homoerotic Desire. Iowa City: U of Iowa P, 1999. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Bergeron, David M.King James’s Civic Pageant and Parliamentary Speech in March 1604.

Albion 34.2 (2002): 213–231. doi:10.2307/4053700.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Carleton, Dudley.Letter to John Chamberlain, 7 January 1605.

Dudley Carleton to John Chamberlain, 1603–1624: Jacobean Letters. Ed. Maurice Lee Jr. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers UP, 1972. 55.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Clifford, Anne. The Diaries of Lady Anne Clifford. Ed. D.J.H. Clifford. London: Alan Sutton, 1990.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Cuddy, Neil.The Revival of the Entourage: The Bedchamber of James I, 1603–1625.

The English Court: From the Wars of the Roses to the Civil War. Ed. David Starkey. London: Longman, 1987. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Daniel, Samuel. The Vision of the 12 Goddesses, Presented in a Maske the 8 of January, at Hampton Court by the Queenes Most Excellent Majestie, and her Ladies. London: Printed by T. C. for Simon Waterson, and are to be Sold at his SThis text has been supplied. Reason: Misprint or typesetting error. Evidence: The text has been supplied based on an external source. ()hop in Pauls Church-yard, at the Signe of the Crowne, 1604. STC 6265. Reprint. EEBO. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Fields, Jemma.The Wardrobe Goods of Anna of Denmark, Queen Consort of Scotland and England (1574–1619).

Costume 51.1 (2017): 3–27. doi:10.3366/cost.2017.0003.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Giustinian, Zorzi.Letter to the Doge and Senate, 24 January 1608.

Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts Relating to English Affairs, Existing in the Archives and Collections of Venice, and in Other Libraries of Northern Italy. Ed. Rawdon Brown, G. Cavendish Bentinck, H.F. Brown, and A.B. Hinds. Vol. 11. London: Longman, 1947. 86.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Goldberg, Jonathan.James I and the Theatre of Conscience.

ELH 46.3 (1979): 379–398. doi:10.2307/2872686.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Goldberg, Jonathan. James I and the Politics of Literature: Jonson, Shakespeare, Donne, and Their Contemporaries. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1983. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

James VI and I. Letters of King James VI and I. Ed. G.P.V. Akrigg. Berkeley: U of California P, 1984. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Jonson, Ben. The First, of Blacknesse, Personated at the Court, at White-hall, on the Twelfth Night, 1605. The Characters of Two Royall Masques: The One of Blacknesse, the Other of Beautie. Personated by the Most Magnificent of Queenes Anne Queene of Great Britaine, &c. with her Honorable Ladyes, 1605 and 1608 at White-hall. London : For Thomas Thorp, and are to be Sold at the Signe of the Tigers Head in Paules Church-yard, 1608. Sig. A3r-C2r. STC 14761. Reprint. EEBO. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Lemon, Robert and Mary Anne Everett Green, eds. Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, of the Reigns of Edward VI, Mary, Elizabeth, and James I, 1547–1625. Vol. 8. London: Longman, 1872.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Lewalski, Barbara Kiefer. Writing Women in Jacobean England. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1993. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Nichols, John Gough. The Progresses, Processions, and Magnificent Festivities of King James the First, His Royal Consort, Family, and Court. 4 vols. New York: Burt Franklin, 1967. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Parry, Graham. The Golden Age Restor’d: The Culture of the Stuart Court, 1603–1642. New York: St. Martin’s, 1981. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Parry, Graham.The Politics of the Jacobean Masque.

Theatre and Government under the Early Stuarts. Ed. J.R. Mulryne and Margaret Shewring. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1993. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Pugh, T.B.A Portrait of Queen Anne of Denmark at Parham Park, Sussex.

The Seventeenth Century 8 (1993): 167–180.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Reynolds, Anna. In Fine Style: The Art of Tudor and Stuart Fashion. London: Royal Collection Trust, 2013. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Rhodes, Neill, Jennifer Richards, and Joseph Marshall, eds. King James VI and I: Selected Writings. By James VI and I. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Roper, Louis H.Unmasquing the Connections Between Jacobean Politics and Policy: The Circle of Anna of Denmark and the Beginning of the English Empire, 1614–18.

High and Mighty Queens of Early Modern England: Realities and Representations. Ed. Carole Levin, Jo Eldridge Carney, and Debra Barret. New York: Palgrave, 2003. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Shephard, Robert.Sexual Rumours in English Politics: The Cases of Elizabeth I and James I.

Desire and Discipline: Sex in Premodern Europe. Ed. Jacqueline Murray and Konrad Eisenbichler. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1996. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Stone, Lawrence. The Causes of the English Revolution, 1525–1642. New York: Harper and Row, 1972. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Wade, Mara R.The Queen’s Courts: Anna of Denmark and Her Royal Sisters: Cultural Agency at Four Northern European Courts in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries.

Women and Culture at the Courts of the Stuart Queens. Ed. Clare McManus. New York: Palgrave, 2003. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Walker, P., and A. MacDonald, eds. Letters to King James the Sixth from the Queen, Prince Henry, Prince Charles, the Princess Elizabeth and Her Husband Frederick King of Bohemia, and Their Son Prince Frederick Henry. Edinburgh: The Maitland Club, 1835.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Williams, Ethel Carleton. Anne of Denmark: Wife of James VI of Scotland, James I of England. London: Longman, 1970. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Williamson, J.W. The Myth of the Conqueror, Prince Henry Stuart: A Study in Seventeenth-Century Personation. New York: AMSP, 1978. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Wilson, Arthur. The History of Great Britain, Being the Life and Reign of King James I, Relating to What Passed From His First Access to the Crown, to His Death. London: Printed for Richard Lownds, and are to be sold at the Sign of the White Lion near Saint Paul’s little North-door, 1653. Wing. 2888. Reprint. EEBO. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Young, Michael B. King James I and the History of Homosexuality. New York: New York UP, 2000. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

Cite this page

MLA citation

.

Anne of Denmark.The Map of Early Modern London, edited by , U of Victoria, 15 Sep. 2020, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/ANNE5.htm.

Chicago citation

.

Anne of Denmark.The Map of Early Modern London. Ed. . Victoria: University of Victoria. Accessed September 15, 2020. https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/ANNE5.htm.

APA citation

2020. Anne of Denmark. In (Ed), The Map of Early Modern London. Victoria: University of Victoria. Retrieved from https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/ANNE5.htm.

RIS file (for RefMan, EndNote etc.)

Provider: University of Victoria Database: The Map of Early Modern London Content: text/plain; charset="utf-8" TY - ELEC A1 - Thomas, Courtney ED - Jenstad, Janelle T1 - Anne of Denmark T2 - The Map of Early Modern London PY - 2020 DA - 2020/09/15 CY - Victoria PB - University of Victoria LA - English UR - https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/ANNE5.htm UR - https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/xml/standalone/ANNE5.xml ER -

RefWorks

RT Web Page SR Electronic(1) A1 Thomas, Courtney A6 Jenstad, Janelle T1 Anne of Denmark T2 The Map of Early Modern London WP 2020 FD 2020/09/15 RD 2020/09/15 PP Victoria PB University of Victoria LA English OL English LK https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/ANNE5.htm

TEI citation

<bibl type="mla"><author><name ref="#THOM10"><surname>Thomas</surname>, <forename>Courtney</forename>

<forename type="middle">Erin</forename></name></author>. <title level="a">Anne of

Denmark</title>. <title level="m">The Map of Early Modern London</title>, edited by

<editor><name ref="#JENS1"><forename>Janelle</forename> <surname>Jenstad</surname></name></editor>,

<publisher>U of Victoria</publisher>, <date when="2020-09-15">15 Sep. 2020</date>,

<ref target="https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/ANNE5.htm">mapoflondon.uvic.ca/ANNE5.htm</ref>.</bibl>

Personography

-

Joey Takeda

JT

Programmer, 2018-present. Junior Programmer, 2015-2017. Research Assistant, 2014-2017. Joey Takeda was a graduate student at the University of British Columbia in the Department of English (Science and Technology research stream). He completed his BA honours in English (with a minor in Women’s Studies) at the University of Victoria in 2016. His primary research interests included diasporic and indigenous Canadian and American literature, critical theory, cultural studies, and the digital humanities.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Introduction

-

Author of Stub

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Copy Editor and Revisor

-

Data Manager

-

Date Encoder

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Bibliography)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Agas)

-

Junior Programmer

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Encoder

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Post-conversion processing and markup correction

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Second Author

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Editor

Contributions by this author

Joey Takeda is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Joey Takeda is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Katie Tanigawa

KT

Project Manager, 2015-2019. Katie Tanigawa was a doctoral candidate at the University of Victoria. Her dissertation focused on representations of poverty in Irish modernist literature. Her additional research interests included geospatial analyses of modernist texts and digital humanities approaches to teaching and analyzing literature.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Conceptor

-

Encoder

-

GIS Specialist

-

Managing Editor

-

Markup Editor

-

Name Encoder

-

Project Manager

-

Proofreader

-

Second Author

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Katie Tanigawa is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Katie Tanigawa is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Tye Landels-Gruenewald

TLG

Data Manager, 2015-2016. Research Assistant, 2013-2015. Tye completed his undergraduate honours degree in English at the University of Victoria in 2015.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

MoEML Researcher

-

Name Encoder

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

Contributions by this author

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kim McLean-Fiander

KMF

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach, 2015–present. Associate Project Director, 2015–present. Assistant Project Director, 2013-2014. MoEML Research Fellow, 2013. Kim McLean-Fiander comes to The Map of Early Modern London from the Cultures of Knowledge digital humanities project at the University of Oxford, where she was the editor of Early Modern Letters Online, an open-access union catalogue and editorial interface for correspondence from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. She is currently Co-Director of a sister project to EMLO called Women’s Early Modern Letters Online (WEMLO). In the past, she held an internship with the curator of manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library, completed a doctorate at Oxford on paratext and early modern women writers, and worked a number of years for the Bodleian Libraries and as a freelance editor. She has a passion for rare books and manuscripts as social and material artifacts, and is interested in the development of digital resources that will improve access to these materials while ensuring their ongoing preservation and conservation. An avid traveler, Kim has always loved both London and maps, and so is particularly delighted to be able to bring her early modern scholarly expertise to bear on the MoEML project.Roles played in the project

-

Associate Project Director

-

Author

-

Author of MoEML Introduction

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Contributor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Contributor

-

Data Manager

-

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (People)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Managing Editor

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Research Fellow

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Proofreader

-

Second Author

-

Secondary Author

-

Secondary Editor

-

Toponymist

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Kim McLean-Fiander is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Kim McLean-Fiander is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Janelle Jenstad

JJ

Janelle Jenstad is Associate Professor of English at the University of Victoria, Director of The Map of Early Modern London, and PI of Linked Early Modern Drama Online. She has taught at Queen’s University, the Summer Academy at the Stratford Festival, the University of Windsor, and the University of Victoria. With Jennifer Roberts-Smith and Mark Kaethler, she co-edited Shakespeare’s Language in Digital Media (Routledge). She has prepared a documentary edition of John Stow’s A Survey of London (1598 text) for MoEML and is currently editing The Merchant of Venice (with Stephen Wittek) and Heywood’s 2 If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody for DRE. Her articles have appeared in Digital Humanities Quarterly, Renaissance and Reformation,Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Early Modern Literary Studies, Elizabethan Theatre, Shakespeare Bulletin: A Journal of Performance Criticism, and The Silver Society Journal. Her book chapters have appeared (or will appear) in Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society (Brill, 2004), Shakespeare, Language and the Stage, The Fifth Wall: Approaches to Shakespeare from Criticism, Performance and Theatre Studies (Arden/Thomson Learning, 2005), Approaches to Teaching Othello (Modern Language Association, 2005), Performing Maternity in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2007), New Directions in the Geohumanities: Art, Text, and History at the Edge of Place (Routledge, 2011), Early Modern Studies and the Digital Turn (Iter, 2016), Teaching Early Modern English Literature from the Archives (MLA, 2015), Placing Names: Enriching and Integrating Gazetteers (Indiana, 2016), Making Things and Drawing Boundaries (Minnesota, 2017), and Rethinking Shakespeare’s Source Study: Audiences, Authors, and Digital Technologies (Routledge, 2018).Roles played in the project

-

Annotator

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Stub

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

Author of Textual Introduction

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Copyeditor

-

Course Instructor

-

Course Supervisor

-

Course supervisor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Structure and Toponyms)

-

Final Markup Editor

-

GIS Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Modern)

-

Geographical Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Main Transcriber

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Project Director

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Name Encoder

-

Peer Reviewer

-

Primary Author

-

Project Director

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Reviewer

-

Reviser

-

Revising Author

-

Second Author

-

Second Encoder

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Janelle Jenstad is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Janelle Jenstad is mentioned in the following documents:

Janelle Jenstad authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Jenstad, Janelle.

Building a Gazetteer for Early Modern London, 1550-1650.

Placing Names. Ed. Merrick Lex Berman, Ruth Mostern, and Humphrey Southall. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 2016. 129-145. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

The Burse and the Merchant’s Purse: Coin, Credit, and the Nation in Heywood’s 2 If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody.

The Elizabethan Theatre XV. Ed. C.E. McGee and A.L. Magnusson. Toronto: P.D. Meany, 2002. 181–202. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Early Modern Literary Studies 8.2 (2002): 5.1–26..The City Cannot Hold You

: Social Conversion in the Goldsmith’s Shop. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

The Silver Society Journal 10 (1998): 40–43.The Gouldesmythes Storehowse

: Early Evidence for Specialisation. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Lying-in Like a Countess: The Lisle Letters, the Cecil Family, and A Chaste Maid in Cheapside.

Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 34 (2004): 373–403. doi:10.1215/10829636–34–2–373. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Public Glory, Private Gilt: The Goldsmiths’ Company and the Spectacle of Punishment.

Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society. Ed. Anne Goldgar and Robert Frost. Leiden: Brill, 2004. 191–217. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Smock Secrets: Birth and Women’s Mysteries on the Early Modern Stage.

Performing Maternity in Early Modern England. Ed. Katherine Moncrief and Kathryn McPherson. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007. 87–99. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Using Early Modern Maps in Literary Studies: Views and Caveats from London.

GeoHumanities: Art, History, Text at the Edge of Place. Ed. Michael Dear, James Ketchum, Sarah Luria, and Doug Richardson. London: Routledge, 2011. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Versioning John Stow’s A Survey of London, or, What’s New in 1618 and 1633?.

Janelle Jenstad Blog. https://janellejenstad.com/2013/03/20/versioning-john-stows-a-survey-of-london-or-whats-new-in-1618-and-1633/. -

Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. Ed. Janelle Jenstad. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ & nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. Ed. Janelle Jenstad and the MoEML Team. MoEML. Transcribed. Web.

-

-

Mara Wade

MW

Roles played in the project

-

Peer Reviewer

-

-

Courtney Thomas

Courtney Erin Thomas CET

Courtney Erin Thomas is an Edmonton-based historian of early modern Britain and Europe. She received her PhD in history and renaissance studies from Yale University (2012) and has previously taught at Yale and MacEwan University. Her work has appeared in several scholarly journals and on the websites Aeon and Executed Today, and her monographIf I Lose Mine Honour I Lose Myself

: Honour Among the Early Modern English Elite was published by the University of Toronto Press in 2017.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Toponymist

Contributions by this author

Courtney Thomas is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Martin D. Holmes

MDH

Programmer at the University of Victoria Humanities Computing and Media Centre (HCMC). Martin ported the MOL project from its original PHP incarnation to a pure eXist database implementation in the fall of 2011. Since then, he has been lead programmer on the project and has also been responsible for maintaining the project schemas. He was a co-applicant on MoEML’s 2012 SSHRC Insight Grant.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Author of abstract

-

Conceptor

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Markup editor

-

Name Encoder

-

Post-conversion and Markup Editor

-

Post-conversion processing and markup correction

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

Contributions by this author

Martin D. Holmes is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Martin D. Holmes is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Dudley Carleton

(b. 10 March 1574, d. 15 February 1632)First Viscount Dorchester. Secretary of State.Dudley Carleton is mentioned in the following documents:

Dudley Carleton authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Carleton, Dudley.

Letter to John Chamberlain, 7 January 1605.

Dudley Carleton to John Chamberlain, 1603–1624: Jacobean Letters. Ed. Maurice Lee Jr. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers UP, 1972. 55.

-

Robert Carr

(b. between 1585? and 1586?, d. 1645)First Earl of Somerset. Favourite of James VI and I.Robert Carr is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Lady Anne Clifford

(b. 30 January 1590, d. 22 March 1676)Countess of Pembroke, Dorset, and Montgomery.Lady Anne Clifford is mentioned in the following documents:

Lady Anne Clifford authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Clifford, Anne. The Diaries of Lady Anne Clifford. Ed. D.J.H. Clifford. London: Alan Sutton, 1990.

-

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 1I Queen of England Queen of Ireland Gloriana Good Queen Bess

(b. 7 September 1533, d. 24 March 1603)Queen of England and Ireland 1558-1603.Elizabeth I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Elizabeth Stuart of Bohemia

Elizabeth Stuart Queen of Bohemia

(b. 1596, d. 1662)Queen of Bohemia 1619-1620. Daughter of James VI and I and Anne of Denmark. Sister of Charles I and Henry Frederick.Elizabeth Stuart of Bohemia is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Zorzi Guistinian

Venetian ambassador in the court of James VI and I.Zorzi Guistinian is mentioned in the following documents:

Zorzi Guistinian authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Giustinian, Zorzi.

Letter to the Doge and Senate, 24 January 1608.

Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts Relating to English Affairs, Existing in the Archives and Collections of Venice, and in Other Libraries of Northern Italy. Ed. Rawdon Brown, G. Cavendish Bentinck, H.F. Brown, and A.B. Hinds. Vol. 11. London: Longman, 1947. 86.

-

Henry VIII

Henry This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 8VIII King of England King of Ireland

(b. 28 June 1491, d. 28 January 1547)King of England and Ireland 1509-1547.Henry VIII is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Henry Frederick

(b. 19 February 1594, d. 6 November 1612)Prince of Wales. Son of James VI and I and Anne of Denmark. Brother of Charles I and Elizabeth Stuart of Bohemia. Died of typhoid fever at the age of eighteen.Henry Frederick is mentioned in the following documents:

-

George Heriot

(b. 15 June 1563, d. 12 February 1624)Jeweller and philanthropist. Husband of Alison Heriot.George Heriot is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Frances Carr (née Howard) is mentioned in the following documents:

-

James VI and I

James This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 6VI This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 1I King of Scotland King of England King of Ireland

(b. 1566, d. 1625)James VI and I is mentioned in the following documents:

James VI and I authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

James VI and I. Letters of King James VI and I. Ed. G.P.V. Akrigg. Berkeley: U of California P, 1984. Print.

-

Rhodes, Neill, Jennifer Richards, and Joseph Marshall, eds. King James VI and I: Selected Writings. By James VI and I. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004.

-

Inigo Jones is mentioned in the following documents:

Inigo Jones authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Jones, Inigo.

Design for the new

1610s. RIBA 12957. Open.Italyan

gate, Arundel House, Strand, London.

-

Ben Jonson is mentioned in the following documents:

Ben Jonson authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Chapman, George, Ben Jonson, and John Marston. Eastward Ho! Ed. R.W. Van Fossen. New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Print.

-

Dekker, Thomas, Stephen Harrison, Ben Jonson, and Thomas Middleton. The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment of King James through the City of London, 15 March 1604, with the Arches of Triumph. Ed. R. Malcolm Smuts. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 219–79.

-

Gifford, William, ed. The Works of Ben Jonson. By Ben Jonson. Vol. 1. London: Nichol, 1816. Remediated by Internet Archive.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Alchemist. London: New Mermaids, 1991. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Bartholomew Fair. Ed. E.A. Horsman. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1979. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Bartholomew Fair. Ed. Suzanne Gossett, based on The Revels Plays edition ed. E.A. Horsman. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2000. Revels Student Editions. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. B. Ion: his part of King Iames his royall and magnificent entertainement through his honorable cittie of London, Thurseday the 15. of March. 1603 so much as was presented in the first and last of their triumphall arch’s. London, 1604. STC 14756. EEBO.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Complete Poetry of Ben Jonson. Ed. William B. Hunter. Stuart Edtions. New York: New YorkUP, 1963.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Devil is an Ass. Ed. Peter Happé. Manchester and New York: Manchester UP, 1996. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Epicene. Ed. Richard Dutton. Revels Plays. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2004. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Every Man Out of His Humour. Ed. Helen Ostovich. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2001. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. The First, of Blacknesse, Personated at the Court, at White-hall, on the Twelfth Night, 1605. The Characters of Two Royall Masques: The One of Blacknesse, the Other of Beautie. Personated by the Most Magnificent of Queenes Anne Queene of Great Britaine, &c. with her Honorable Ladyes, 1605 and 1608 at White-hall. London : For Thomas Thorp, and are to be Sold at the Signe of the Tigers Head in Paules Church-yard, 1608. Sig. A3r-C2r. STC 14761. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Jonson, Ben. Oberon, The Faery Prince. The Workes of Benjamin Jonson. Vol. 1. London: Will Stansby, 1616. Sig. 4N2r-2N6r. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Staple of Newes. The Works. Vol. 2. London: Printed by I.B. for Robert Allot, 1631. Sig. 2A1r-2J2v. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Staple of News. Ed. Anthony Parr. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben.

To Penshurst.

The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt, Carol T. Christ, Alfred David, Barbara K. Lewalski, Lawrence Lipking, George M. Logan, Deidre Shauna Lynch, Katharine Eisaman Maus, James Noggle, Jahan Ramazani, Catherine Robson, James Simpson, Jon Stallworthy, Jack Stillinger, and M. H. Abrams. 9th ed. Vol. B. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2012. 1547. -

Jonson, Ben. The vvorkes of Beniamin Ionson. Containing these playes, viz. 1 Bartholomew Fayre. 2 The staple of newes. 3 The Divell is an asse. London, 1641. EEBO. Reprint. Subscr. STC 14754.

-

Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary Queen of Scotland

(b. 1542, d. 1587)Queen of Scotland 1542-1567. Queen of France 1559-1560.Mary, Queen of Scots is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Sir Thomas Overbury is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Sir Walter Raleigh is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Lucy Russell (née Harington)

Lucy Russell Harington

(bap. 25 January 1581, d. 26 May 1627)Countess of Bedford. Courtier and patron of the arts.Lucy Russell (née Harington) is mentioned in the following documents:

-

George Villers

(b. 28 August 1592, d. 23 August 1628)First Duke of Buckingham. Favourite of James VI and I and Charles I.George Villers is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Robert Devereux

(b. 11 January 1591, d. 9 October 1646)Third Earl of Essex. Son of Robert Devereux.Robert Devereux is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Whitgift

John Whitgift Archbishop of Canterbury

(b. between 1530? and 1531?, d. 29 February 1604)Archbishop of Canterbury 1583-1604.John Whitgift is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Tycho Brahe is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Rudolf II of Habsburg

Rudolf This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 2II King of Bohemia King of Germany Holy Roman Emperor

(b. 18 July 1552, d. 20 January 1612)King of Bohemia 1576–1611. King of Germany 1575–1612. Holy Roman Emperor 1576-1612.Rudolf II of Habsburg is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Frederick II of Denmark

Frederick This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 2II King of Denmark King of Norway

(b. 1 July 1534, d. 4 April 1588)King of Denmark and Norway 1559-1588. Husband of Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow. Father of Anne of Denmark, Christian IV of Denmark, and Elizabeth of Denmark.Frederick II of Denmark is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow

Sophie Queen consort of Denmark Queen consort of Norway

(b. 4 September 1557, d. 14 October 1631)Queen of Denmark and Norway 1572–1588. Wife of Frederick II of Denmark. Mother of Anne of Denmark, Christian IV of Denmark, and Elizabeth of Denmark.Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Anne of Denmark

Anne Queen consort of Scotland Queen consort of England Queen consort of Ireland

(b. 12 December 1574, d. 2 March 1619)Queen consort of Scotland 1589–1619. Queen consort of England and Ireland 1603–1619. Wife of James VI and I. Daughter of Frederick II of Denmark and Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow. Sister of Christian IV of Denmark, Elizabeth of Denmark, and Ulric of Denmark.Anne of Denmark is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Christian IV of Denmark

Christian This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 4IV King of Denmark King of Norway

(b. 12 April 1577, d. 28 February 1648)King of Denmark and Norway 1588-1648. Son of Frederick II of Denmark and Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow. Brother of Anne of Denmark, Elizabeth of Denmark, and Ulric of Denmark.Christian IV of Denmark is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Elizabeth of Denmark

Elizabeth

(b. 25 August 1573, d. 19 July 1625)Duchess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. Wife of Heinrich Julius. Daughter of Frederick II of Denmark and Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow. Sister of Anne of Denmark, Christian IV of Denmark, and Ulric of Denmark.Elizabeth of Denmark is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Heinrich Julius

(b. 15 October 1564, d. 30 July 1613)Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and Prince of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. Husband of Elizabeth of Denmark.Heinrich Julius is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Ulric of Denmark

Ulric Bishop of Schleswig

(b. 30 December 1578, d. 27 March 1624)Bishop of Schleswig 1602–1624. Son of Frederick II of Denmark and Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow. Brother of Anne of Denmark, Christian IV of Denmark, and Elizabeth of Denmark.Ulric of Denmark is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Lady Margaret Stuart

(b. 24 December 1598, d. August 1600)Daughter of James VI and I and Anne of Denmark. Died in infancy.Lady Margaret Stuart is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Mary Stuart is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Sophia Stuart is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Robert Stuart

(b. 18 January 1602, d. 27 May 1602)Duke of Kintyre. Son of James VI and I and Anne of Denmark. Died in infancy.Robert Stuart is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Frederick V of the Palatinate

Frederick This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 5V

(b. 26 August 1596, d. 29 November 1632)Elector Palatinate of the Rhine. Husband of Elizabeth Stuart of Bohemia.Frederick V of the Palatinate is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Henry Stuart

Henry Stuart King of Scotland

(b. 7 December 1545, d. between 9 February 1567 and 10 February 1567)Lord Darnley. King of Scotland 1565–1567. Husband of Mary, Queen of Scots. Father of James VI and I.Henry Stuart is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Anne Lyon (née Murray)

Anne Lyon Murray

(b. 1579, d. 27 February 1618)Countess of Kinghorne. Alleged mistress of James VI and I.Anne Lyon (née Murray) is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Paul van Somer

(b. 1577, d. between 1621 and 5 January 1622)Flemish painter. Active in the court of James VI and I.Paul van Somer is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Simon van de Passe is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger

(b. between 1561 and 1562, d. 19 January 1636)Flemish painter. Active in the courts of Elizabeth I and James VI and I.Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger is mentioned in the following documents:

Locations

-

Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey was a historically significant church, located on the bottom-left corner of the Agas map. Colloquially known asPoets’ Corner,

it is the final resting place of Geoffrey Chaucer, Ben Jonson, Francis Beaumont, and many other notable authors; in 1740, a monument for William Shakespeare was erected in Westminster Abbey (ShaLT).Westminster Abbey is mentioned in the following documents:

-

London is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Queen’s House is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Greenwich is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Somerset House

Somerset House (labelled asSomerſet Palace

on the Agas map) was a significant site for royalty in early modern London. Erected in 1550 on The Strand between Ivy Bridge Lane and Strand Lane, it was built for Lord Protector Somerset and was was England’s first Renaissance palace.Somerset House is mentioned in the following documents:

-

The Strand

Named for its location on the bank of the Thames, the Strand leads outside the City of London from Temple Bar through what was formerly the Duchy of Lancaster to Charing Cross in what was once the city of Westminster. There were three main phases in the evolution of the Strand in early modern times: occupation by the bishops, occupation by the nobility, and commercial development.The Strand is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Tower of London is mentioned in the following documents:

Organizations

-

Corporation of London

The Corporation of London was the municipal government of London, made up of the Mayor of London, the Court of Aldermen, and the Court of Common Council. It exists today in largely the same form.Roles played in the project

-

Author

Contributions by this author

This organization is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Council of the Regency

The Council of the Regency was established by King James VI and I in 1617 to govern England while he visited Scotland.This organization is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was a legislative branch of the Kingdom of England, founded by William the Conquerer in 1066.This organization is mentioned in the following documents: