Ram Alley

¶Location

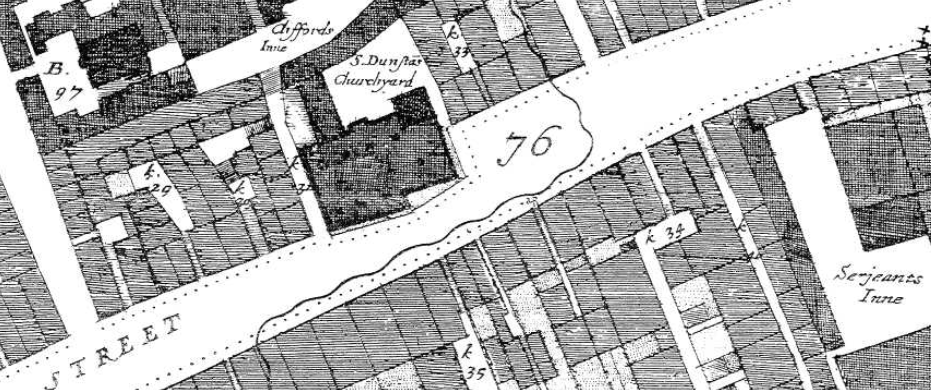

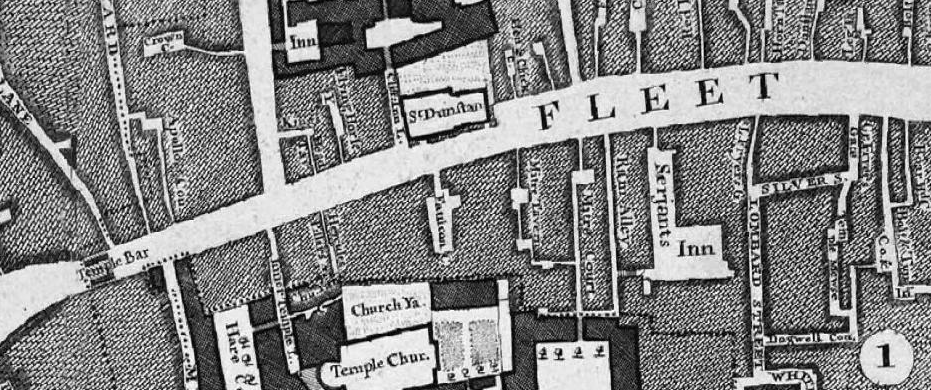

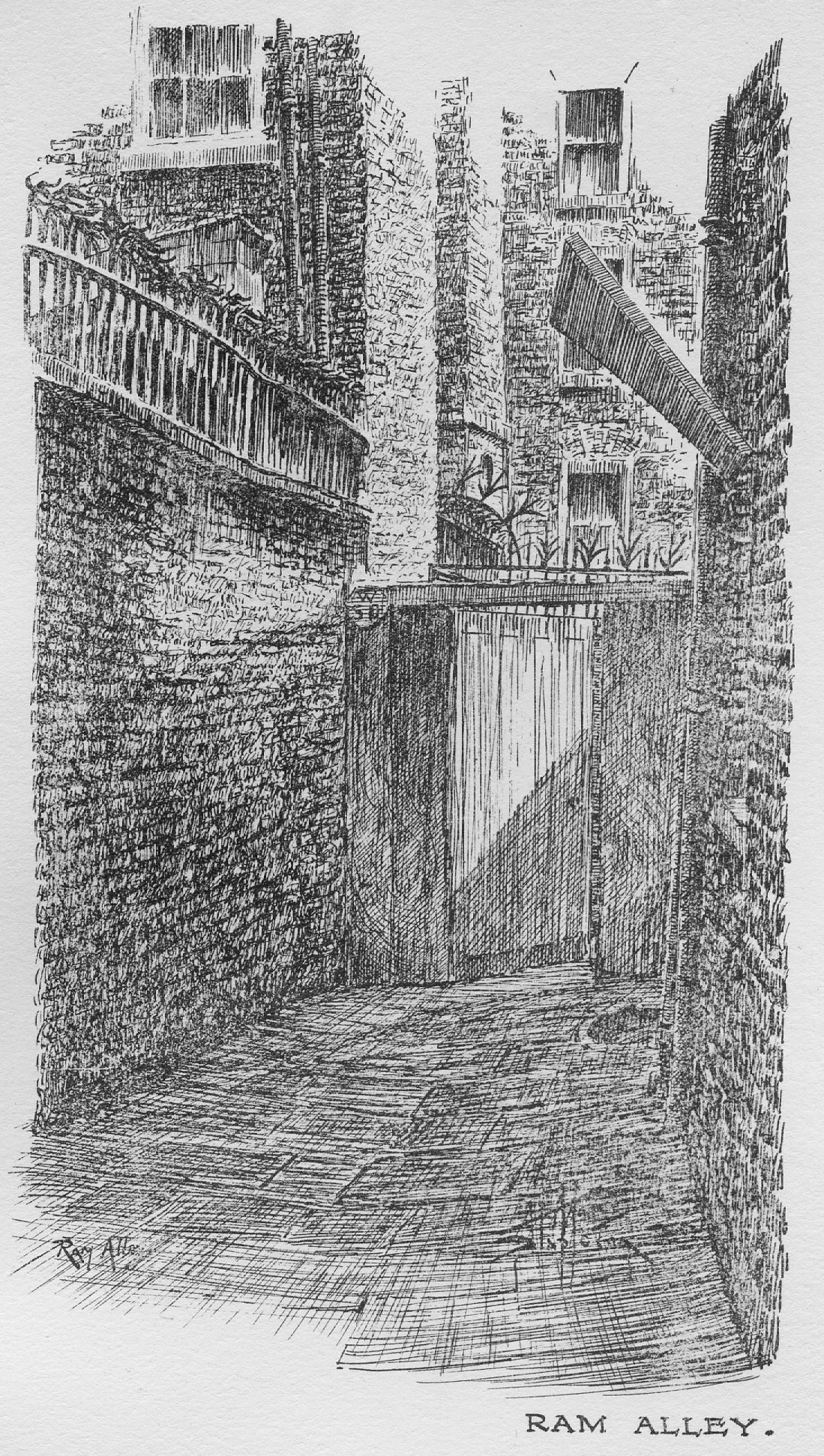

Ram Alley, a mere seven feet wide, ran southwards from Fleet Street, opposite Fetter Lane. Its end point was a footway between two legal institutions: the Inner Temple and Serjeants Inn. Edward H. Sugden also mentions that the street was well known as the rear exit from another inn, the

Mitre, which fronted onto Fleet Street.

¶Etymology

The alley was named after an inn, marked by the sign of the Star and Ram, which had originally belonged to the Knights Hospitallers but was confiscated by Henry VIII. It was taken in fee from the monarch for £54 by Robert Harrys, or Harris, and became the site of his brewery, which had a frontage on Fleet Street (Bell 247). The alley is now known as Hare Place, named after Hare House (Paige letter #154).

¶Map Views

An unlabelled alley in the correct location as Ram Alley appears on the Agas map. The alley is marked on both the Ogilby and Morgan map of 1676 and the Rocque map of 1746.

¶Significance

Ram Alley was a place of sanctuary for criminals. Those seeking to evade capture would run

into Ram Alley, which, like the Whitefriars nearby, still claimed right of sanctuary: that is, the immunity from arrest. A 1603 source cited by William Kent comments that

there is a door leading out of Ram Alley to the tenement called the in Fleet-streete, by which means thereof such persons as do frequent the house upon search made after them are conveyed out that way(Kent 494). The freedom was requested under common law by several of the London liberties, many of which were formerly monastic land.1 In an area known from the seventeenth century as Alsatia,2 Ram Alley was particularly renowned as a place of refuge for those in debt, and was

the resort of sharpers and necessitous persons of very ill fame, and of both sexes(Nares 719). Even in 1640, a debtor taking refuge in Ram Alley was considered by his creditor beyond pursuit (Calendar of State Papers Domestic: Charles I, 1639-40 February 20). Sugden notes,

[i]t was a place of evil reputation, inhabited chiefly by cooks, bawds, tobacco-sellers, and ale-house keepersand adds that

[t]he worst of its dens was the Maidenhead, near the Temple end of it(Sugden 426). Walter George Bell calls it

Ram Alley of evil association, perhaps the most pestilent court in London(Bell 252). Perhaps this unsavoury reputation is why it is not mentioned by John Stow in A Survey of London.

Parish records show a fear that the alley should become a refuge of the poor, with

residents taking in unwelcome lodgers—particularly foreigners—into their midst. One

such incident is noted in the wardmote inquests of St. Dunstan from 1598:

Item, we present Margaret Lylly, who came to dwell in Ram Alley within three months last past and lodgeth one Symon Dominico, a frenchman borne and his wife in her house, who Gap in transcription. Reason: Editorial omission for reasons of length or relevance. Use only in quotations in born-digital documents.[…] are like to be a charge to the p’ishe and the cittie(St. Dunstan’s parish reigsters, 1598 qtd. in Bell 244).

¶Literary References

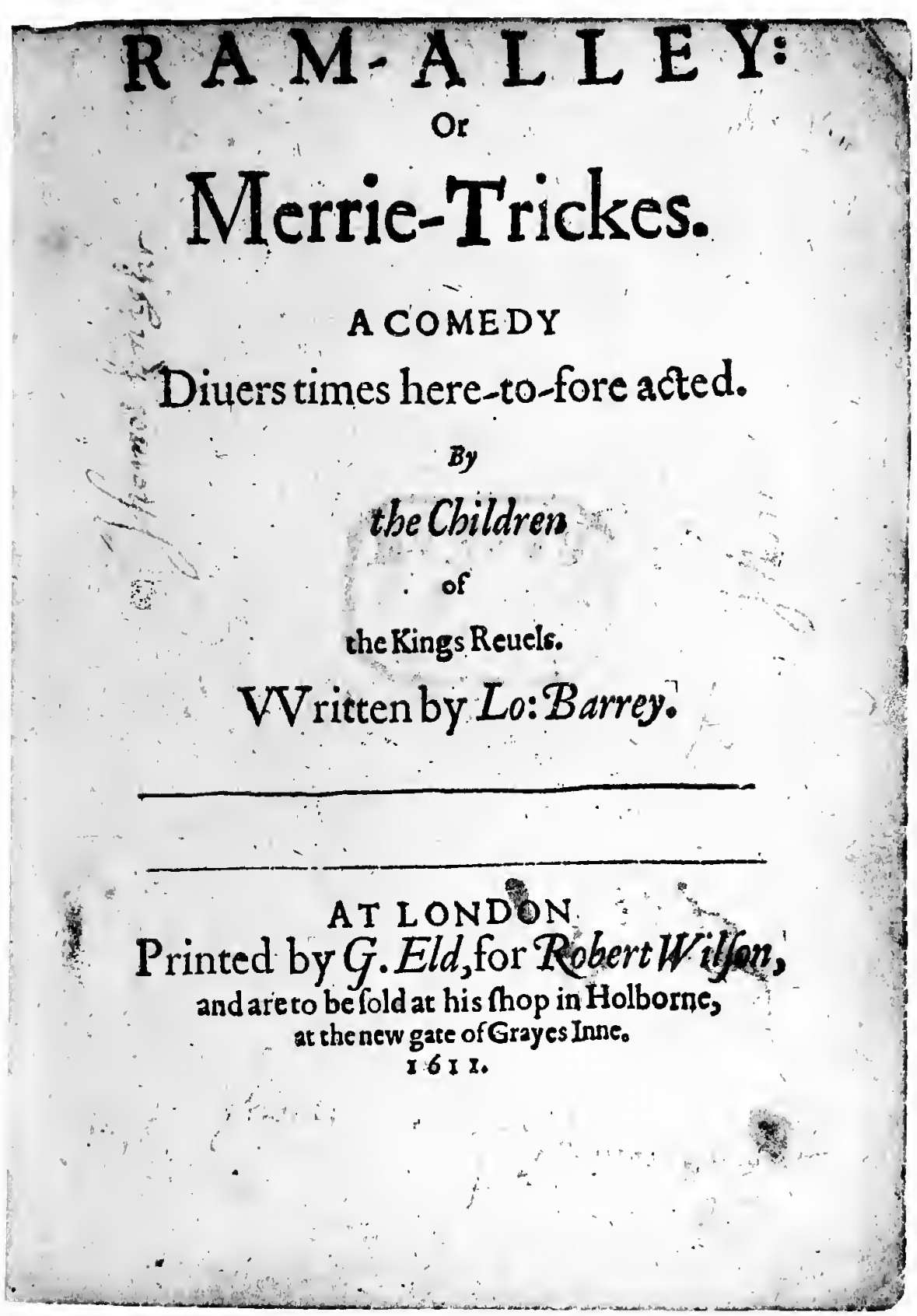

The eponymous setting of a comic play, Ram Alley’s famous inns were invoked by Lording Barry, who juxtaposes them with its lawyers and prostitutes. Written in 1607-8, the play was performed by the short-lived Children of the King’s Revels company, based in the theatre at Whitefriars and funded by a group of investors including Barry.3 In the play, Throat, a dubious man of law who perhaps has his qualification from an Inn of Chancery, comments on the conjunction of food, drink and legal work:

And though Ramme ſtinks with Cookes and ale, / Yet ſay thers many a worthy lawyers chamber, / Buts vpon Rame-alley(Barry sig. C1v). Later, he makes reference to the predatory sexuality for which the area was also known, demanding,

Elizabeth Hanson comments on the play’sWill you be gon directly, are you mad?Come you to ſeeke a Virgin in Ram-alleySoe neere an Inne of Court, and amongſt Cookes,Ale-men, and Landreſſes, why are you fooles?

(Barry sig. E4v)

geographical and social specificity(Hanson 233), but, in his essay on the relationship between the audience and actors in the play, Jeremy Lopez nuances this point, arguing that the play

seems to be about being in Ram Alley, but it’s really about its spectators knowing that they’re not(Lopez 202). He suggests that the play portrays the area and uses its stereotypical attributes to appeal to those playgoers who lived in the city but outside the area of the Whitefriars itself.

The alley is referred to by several other contemporary writers, who also focus on

its key associations. The alley’s reputation as a place to flee the forces of the

law is again shown in Richard Brome’s A Mad Couple Well-Match’d, where the spendthrift nephew, Careless, takes sanctuary from his uncle and other creditors in Ram Alley. Having got hold of money, he announces,

I need no more inſconſing now in Ram-alley, nor the Sanctuary of White-fryers, the Forts of Fullers-rents, and Milford-lane, whoſe walls are dayly batter’d wth the curſes of bawling creditors(Brome, A Mad Couple Well-Match’d sig. C8r), giving a list of places where men could evade pursuit. In The Damoiselle, Brome continues the association of Ram Alley with sanctuary, as Bumpsey, looking for his son-in-law, enters the alley to seek information:

Ille but ſtep up / Into Ram-Alley-Sanctuary, to Debtor, / That praies and watches there for a Protection(Brome, The Damoiselle E4r).

The Rabelaisian account of the area in The Floating Island (1673) by writer and bookseller Richard Head also focuses on the alley’s reputation as a refuge from pursuit. The supposed writer

of the work explains its origins in a period of forced inertia in Ramallia, or Villa

Franca,

a Sanctuary to all perſons whatſoever(Head sig. A2v).

It was,he tells his reader in a prefatory epistle, an account of an imaginary journey

pen’d laſt long Vacation, when all I had to do, was to hide my ſelf from the Inquiſition of my cruel Creditors; for which purpoſe I lodg’d in Ram-alley(Head sig. A2r).

Writing the satirical The Second Return from Parnassus seventy years before Richard Head’s, the students of St John’s College, Cambridge, associate the alley with the belligerence

and linguistic directness of playwright John Marston, who lived as a legal student in the Middle Temple nearby:

[Marston] Cutts, thruſts, and foines at whomeſoeuer he meets,And ſtrowes about Ram-ally meditations.Tut, what cares he for modeſt cloſe coucht termes,Cleanly to gird our looſer libertines?

(The Second Part of The Return from Parnassus sig. B2v)

The association of the alley with food and drink is demonstrated by Ben Jonson’s Lickfinger, the thieving cook in The Staple of News, who is labelled

mine old hoſt of Ram-Alley(Jonson 2D2v). In Philip Massinger’s A New Way to Pay Old Debts, this connection with food is again linked to the quotidian practices of nearby lawyers when Amble says of Marrall, the attorney:

[t]he knaue thinkes ſtill hee’s at the cookes ſhop in Ramme-alley, / Where the Clarkes diuide and the Elder is to chooſe(Massinger sig. E2v). Thomas Nashe, in his Prognostication, shows that the association with food could be combined with the alley’s reputation for roguery:

but let the fiſh-wiues take heede, for if moſt of them proue not ſcoldes Gap in transcription. Reason: Editorial omission for reasons of length or relevance. Use only in quotations in born-digital documents.[…] they ſhall weare out more ſhooes in Lent then in anie two months beſide through the whole yeere, and get their liuing by walking and crying, becauſe they ſlaundered Ram alley with ſuch a tragical infamie(Nash sig. B4v). Sugden suggests the fishwives may have harangued the cooks of Ram Alley because they illicitly sold flesh on Fridays or in Lent.

The provision of food is connected with the area’s predatory sexuality, which had

been referred to so casually in Barry’s play, in a salacious pamphlet of 1681 called Whipping Tom. In the account made of Tom’s sexual attacks upon London women, there features one on

the Woman that cries hot Gray Peaſe about the Streets, coming up Ram Alley in Fleete-ſtreet(Whipping Tom sig. A1v). Having laid on her his

cold hand,she

loſt all power of Reſiſtance,and along with it her peas, which she had afterwards to

ſcrape up her Ware as well as ſhe could, for the uſe of ſuch longing Ladies as are affected with ſuch Diet(Whipping Tom sig. A1v).

As well as food and drink, the area was also known for another popular vice in the

early modern capital, the smoking of tobacco—the supplying or indulgence of which

habit was often found unacceptable by the members of the legal profession whose property

abutted the alley. The St. Dunstan’s wardmote register of 1630 records one such offence:

Item, we present Timothy Howe (of Ram Alley, Fleet Street) and Humfry Fenne for annoying the Judges at Serjeants Inn with the stench and smell of their tobacco(St. Dunstan’s parish reigsters, 1630 qtd. in Bell 274). Bell continues to quote the wardmote from 1618 which combined complaints about drink with those against tobacco. The register

laid complaint against Timothy Louse and John Barker, of Ram Alley,(St. Dunstan’s parish reigsters, 1618 qtd. in Bell 274).for keeping their tobacco shoppes open all night and fyers in the same without any chimney and suffering hot waters [spirits] and selling also without licence, to the great disquietness and annoyance of that neighbourhood

Finally, in The Blind Beggar of Bethnal Green, John Day and his collaborator, Henry Chettle, make use of the alley’s fame as a place of popular recreation. Disguised as a

Maſter of the Motionor puppet-master, Canby promises his customers, Tom Strowd and Swash,

you ſhall likewiſe ſee the amorous conceits and Love ſongs betwixt Captain Pod of Py-corner, and Mrs. Rump of Ram-alley(Day sig. G1v-G2r). Sugden notes that Captain Pod was a well-known exhibitor of puppet shows, and that it may be presumed Mrs. Rump was equally historical.

The modern day Hare Place remains an alleyway cutting through to the Inner Temple from Fleet Street, and appropriately emerging next to a wine merchant.

Notes

- Mary Bly discusses right of sanctuary granted to the monastic liberties by Henry VIII. (JW)↑

- See

Chapter XIII

of Bell’s Fleet Street in Seven Centuries, which examines the area’s history as a place of sanctuary and the use of this cant name. In 1688, Thomas Shadwell wrote a popular play set in the area called The Squire of Alsatia. See also John Levin’s Alsatia: The Debtor Sanctuaries of London blog. (JW)↑ - For more information about the Children of the King’s Revels, and the typicality of Ram Alley in that company’s repertoire, see Bly (2000). (JW)↑

References

-

Citation

Barry, Lording. Ram-Alley: Or Merrie-Trickes. London: Printed by G. Eld. for Robert Wilson, 1611. Reprint. EEBO. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Bell, Walter George. Fleet Street in Seven Centuries: Being a History of the Growth of London Beyond the Walls into the Western Liberty, and of Fleet Street to Our Time. London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons, 1912. Remediated by Internet Archive.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Beresford, Edwin. The Annals of Fleet Street. London: Chapman & Hall Limited, 1912. Remediated by Internet Archive. -

Citation

Bly, Mary. Queer Virgins and Virgin Queans on the Early Modern Stage. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2000. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Bly, Mary.Playing the Tourist in Early Modern London: Selling the Liberties Onstage.

PMLA 122.1 (2007): 61–71. doi:10.1632/pmla.2007.122.1.61.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Brome, Richard. A Mad Couple Well-Match’d. Five New Playes. London: Humphrey Moseley, Richard Marriot, and Thomas Dring, 1653. Sig. A5v-H2r. Remediated by Richard Brome Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Brome, Richard. The Demoiselle, or the New Ordinary. London: T[homas] R[oycroft] for Richard Marriot, and Thomas Dring, 1653. Remediated by Richard Brome Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Calendar of State Papers Domestic: Charles I, 1639–40. Ed. Wiliam Douglas Hamilton. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1877.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Day, John [and Henry Chettle]. The Blind-beggar of Bednal Green. London: R. Pollard and Tho. Dring, 1659. Reprint. EEBO. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Hanson, Elizabeth.

ELH 72.1 (2005): 209–238.There’s Meat and Money Too

: Rich Widows and Allegories of Wealth in Jacobean City Comedy.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Head, Richard. The Floating Island, or a New Discovery. London: Published by Franck Careless [i.e., Richard Head], 1673. Reprint. EEBO. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Jonson, Ben. The Staple of Newes. The Works. Vol. 2. London: Printed by I.B. for Robert Allot, 1631. Sig. 2A1r-2J2v. Reprint. EEBO. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Kent, William. An Encyclopedia of London. Ed. Godfrey Thompson. Rev. ed. London: J.M. Dent, 1970. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Levin, John. Alsatia: The Debtor Sanctuaries of London. http://alsatia.org.uk/site/about/.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Lopez, Jeremy.Success the Whitefriars Way: Ram Alley and the Negative Force of Acting.

Renaissance Drama 38 (2010): 199–224. doi:10.1353/rnd.2010.0003.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Massinger, Philip. A New Way to Pay Old Debts. London: Printed by E[lizabeth] P[urslowe] for Henry Seyle, 1633. Reprint. EEBO. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Nares, Robert. A Glossary; Or, Collection of Words, Phrases, Names, and Allusions to Customs, Proverbs, etc., which have been Thought to Require Illustration in the Words of English Authors, Particularly Shakespeare and His Contemporaries. New ed. Ed. James O. Halliwell and Thomas Wright. Vol. 2. London: John Russell Smith, 1867. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Nashe, Thomas. A Wonderfull Strange and Miraculous Astrologicall Prognostication for this Yeere 1591. London: Thomas Scarlet, 1591. Reprint. EEBO. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Ogilby, John, and William Morgan. A Large and Accurate Map of the City of London Ichnographically Describing All the Streets, Lanes, Alleys, Courts, Yards, Churches, Halls and Houses, &c. Actually Surveyed and Delineated by John Ogilby, esq., His Majesties Cosmographer. London, 1676. Reprint. The A to Z of Restoration London. Introduced by Ralph Hyde. Indexed by John Fisher and Roger Cline. London: London Topographical Society, 1992. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Paige, John. The Letters of John Paige, London Merchant, 1648–58. Ed. G.F. Steckley. London Record Society 21. London: London Record Society, 1984. British History Online. London: London Record Society, 1984. Open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Rocque, John. A Plan of the Cities of London and Westminster, and Borough of Southwark with Contiguous Buildings. London: Printed by John Rocque, 1746. Reprint. The A to Z of Georgian London. Introduced by Ralph Hyde. London: London Topographical Society, 1982. [We cite by index label thus: Rocque 15Db.]This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Shadwell, Thomas. The Squire of Alsatia. London: Printed for James Knapton, at the Queen’s Head in St. Paul’s Churchyard, 1688. Reprint. EEBO. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Stapleton, Alan. London Alleys, Byways, and Courts. London: Bodley Head Ltd., 1924. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Stow, John. A suruay of London· Conteyning the originall, antiquity, increase, moderne estate, and description of that city, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow citizen of London. Since by the same author increased, with diuers rare notes of antiquity, and published in the yeare, 1603. Also an apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that citie, the greatnesse thereof. VVith an appendix, contayning in Latine Libellum de situ & nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. London: John Windet, 1603. STC 23343. U of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign Campus) copy Reprint. Early English Books Online. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Sugden, Edward. A Topographical Dictionary to the Works of Shakespeare and His Fellow Dramatists. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1925. Remediated by Internet Archive.This item is cited in the following documents:

Cite this page

MLA citation

, and .

Ram Alley.The Map of Early Modern London, edited by , U of Victoria, 26 Jun. 2020, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/RAMA1.htm.

Chicago citation

, and .

Ram Alley.The Map of Early Modern London. Ed. . Victoria: University of Victoria. Accessed June 26, 2020. https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/RAMA1.htm.

APA citation

, & 2020. Ram Alley. In (Ed), The Map of Early Modern London. Victoria: University of Victoria. Retrieved from https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/RAMA1.htm.

RIS file (for RefMan, EndNote etc.)

Provider: University of Victoria Database: The Map of Early Modern London Content: text/plain; charset="utf-8" TY - ELEC A1 - Watson, Jacqueline A1 - Takeda, Joey ED - Jenstad, Janelle T1 - Ram Alley T2 - The Map of Early Modern London PY - 2020 DA - 2020/06/26 CY - Victoria PB - University of Victoria LA - English UR - https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/RAMA1.htm UR - https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/xml/standalone/RAMA1.xml ER -

RefWorks

RT Web Page SR Electronic(1) A1 Watson, Jacqueline A1 Takeda, Joey A6 Jenstad, Janelle T1 Ram Alley T2 The Map of Early Modern London WP 2020 FD 2020/06/26 RD 2020/06/26 PP Victoria PB University of Victoria LA English OL English LK https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/RAMA1.htm

TEI citation

<bibl type="mla"><author><name ref="#WATS2"><surname>Watson</surname>, <forename>Jacqueline</forename></name></author>,

and <author><name ref="#TAKE1"><forename>Joey</forename> <surname>Takeda</surname></name></author>.

<title level="a">Ram Alley</title>. <title level="m">The Map of Early Modern London</title>,

edited by <editor><name ref="#JENS1"><forename>Janelle</forename> <surname>Jenstad</surname></name></editor>,

<publisher>U of Victoria</publisher>, <date when="2020-06-26">26 Jun. 2020</date>,

<ref target="https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/RAMA1.htm">mapoflondon.uvic.ca/RAMA1.htm</ref>.</bibl>

Personography

-

Joey Takeda

JT

Programmer, 2018-present. Junior Programmer, 2015-2017. Research Assistant, 2014-2017. Joey Takeda was a graduate student at the University of British Columbia in the Department of English (Science and Technology research stream). He completed his BA honours in English (with a minor in Women’s Studies) at the University of Victoria in 2016. His primary research interests included diasporic and indigenous Canadian and American literature, critical theory, cultural studies, and the digital humanities.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Introduction

-

Author of Stub

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Copy Editor and Revisor

-

Data Manager

-

Date Encoder

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Bibliography)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Agas)

-

Junior Programmer

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Encoder

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Post-conversion processing and markup correction

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Second Author

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Editor

Contributions by this author

Joey Takeda is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Joey Takeda is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Tye Landels-Gruenewald

TLG

Data Manager, 2015-2016. Research Assistant, 2013-2015. Tye completed his undergraduate honours degree in English at the University of Victoria in 2015.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

MoEML Researcher

-

Name Encoder

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

Contributions by this author

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kim McLean-Fiander

KMF

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach, 2015–present. Associate Project Director, 2015–present. Assistant Project Director, 2013-2014. MoEML Research Fellow, 2013. Kim McLean-Fiander comes to The Map of Early Modern London from the Cultures of Knowledge digital humanities project at the University of Oxford, where she was the editor of Early Modern Letters Online, an open-access union catalogue and editorial interface for correspondence from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. She is currently Co-Director of a sister project to EMLO called Women’s Early Modern Letters Online (WEMLO). In the past, she held an internship with the curator of manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library, completed a doctorate at Oxford on paratext and early modern women writers, and worked a number of years for the Bodleian Libraries and as a freelance editor. She has a passion for rare books and manuscripts as social and material artifacts, and is interested in the development of digital resources that will improve access to these materials while ensuring their ongoing preservation and conservation. An avid traveler, Kim has always loved both London and maps, and so is particularly delighted to be able to bring her early modern scholarly expertise to bear on the MoEML project.Roles played in the project

-

Associate Project Director

-

Author

-

Author of MoEML Introduction

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Contributor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Contributor

-

Data Manager

-

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (People)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Managing Editor

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Research Fellow

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Proofreader

-

Second Author

-

Secondary Author

-

Secondary Editor

-

Toponymist

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Kim McLean-Fiander is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Kim McLean-Fiander is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Janelle Jenstad

JJ

Janelle Jenstad is Associate Professor of English at the University of Victoria, Director of The Map of Early Modern London, and PI of Linked Early Modern Drama Online. She has taught at Queen’s University, the Summer Academy at the Stratford Festival, the University of Windsor, and the University of Victoria. With Jennifer Roberts-Smith and Mark Kaethler, she co-edited Shakespeare’s Language in Digital Media (Routledge). She has prepared a documentary edition of John Stow’s A Survey of London (1598 text) for MoEML and is currently editing The Merchant of Venice (with Stephen Wittek) and Heywood’s 2 If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody for DRE. Her articles have appeared in Digital Humanities Quarterly, Renaissance and Reformation,Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Early Modern Literary Studies, Elizabethan Theatre, Shakespeare Bulletin: A Journal of Performance Criticism, and The Silver Society Journal. Her book chapters have appeared (or will appear) in Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society (Brill, 2004), Shakespeare, Language and the Stage, The Fifth Wall: Approaches to Shakespeare from Criticism, Performance and Theatre Studies (Arden/Thomson Learning, 2005), Approaches to Teaching Othello (Modern Language Association, 2005), Performing Maternity in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2007), New Directions in the Geohumanities: Art, Text, and History at the Edge of Place (Routledge, 2011), Early Modern Studies and the Digital Turn (Iter, 2016), Teaching Early Modern English Literature from the Archives (MLA, 2015), Placing Names: Enriching and Integrating Gazetteers (Indiana, 2016), Making Things and Drawing Boundaries (Minnesota, 2017), and Rethinking Shakespeare’s Source Study: Audiences, Authors, and Digital Technologies (Routledge, 2018).Roles played in the project

-

Annotator

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Stub

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

Author of Textual Introduction

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Copyeditor

-

Course Instructor

-

Course Supervisor

-

Course supervisor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Structure and Toponyms)

-

Final Markup Editor

-

GIS Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Modern)

-

Geographical Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Main Transcriber

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Project Director

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Name Encoder

-

Peer Reviewer

-

Primary Author

-

Project Director

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Reviser

-

Revising Author

-

Second Author

-

Second Encoder

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Janelle Jenstad is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Janelle Jenstad is mentioned in the following documents:

Janelle Jenstad authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Jenstad, Janelle.

Building a Gazetteer for Early Modern London, 1550-1650.

Placing Names. Ed. Merrick Lex Berman, Ruth Mostern, and Humphrey Southall. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 2016. 129-145. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

The Burse and the Merchant’s Purse: Coin, Credit, and the Nation in Heywood’s 2 If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody.

The Elizabethan Theatre XV. Ed. C.E. McGee and A.L. Magnusson. Toronto: P.D. Meany, 2002. 181–202. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Early Modern Literary Studies 8.2 (2002): 5.1–26..The City Cannot Hold You

: Social Conversion in the Goldsmith’s Shop. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

The Silver Society Journal 10 (1998): 40–43.The Gouldesmythes Storehowse

: Early Evidence for Specialisation. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Lying-in Like a Countess: The Lisle Letters, the Cecil Family, and A Chaste Maid in Cheapside.

Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 34 (2004): 373–403. doi:10.1215/10829636–34–2–373. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Public Glory, Private Gilt: The Goldsmiths’ Company and the Spectacle of Punishment.

Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society. Ed. Anne Goldgar and Robert Frost. Leiden: Brill, 2004. 191–217. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Smock Secrets: Birth and Women’s Mysteries on the Early Modern Stage.

Performing Maternity in Early Modern England. Ed. Katherine Moncrief and Kathryn McPherson. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007. 87–99. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Using Early Modern Maps in Literary Studies: Views and Caveats from London.

GeoHumanities: Art, History, Text at the Edge of Place. Ed. Michael Dear, James Ketchum, Sarah Luria, and Doug Richardson. London: Routledge, 2011. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Versioning John Stow’s A Survey of London, or, What’s New in 1618 and 1633?.

Janelle Jenstad Blog. https://janellejenstad.com/2013/03/20/versioning-john-stows-a-survey-of-london-or-whats-new-in-1618-and-1633/. -

Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. Ed. Janelle Jenstad. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ & nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. Ed. Janelle Jenstad and the MoEML Team. MoEML. Transcribed. Web.

-

-

Jacqueline Watson

JW

Jackie Watson completed her PhD at Birkbeck College, London, in 2015, with a thesis looking at the life of the Jacobean courtier, Sir Thomas Overbury, and examining the representations of courtiership on stage between 1599 and 1613. She is co-editor of The Senses in Early Modern England, 1558–1660 (Manchester UP, 2015), to which she contributed a chapter on the deceptive nature of sight. Recent published articles have looked at the early modern Inns of Court and at Innsmen as segments of playhouse audiences. She is currently working on a monograph with a focus on Overbury’s letters, courtiership and the Jacobean playhouse.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Conceptor

Contributions by this author

Jacqueline Watson is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Martin D. Holmes

MDH

Programmer at the University of Victoria Humanities Computing and Media Centre (HCMC). Martin ported the MOL project from its original PHP incarnation to a pure eXist database implementation in the fall of 2011. Since then, he has been lead programmer on the project and has also been responsible for maintaining the project schemas. He was a co-applicant on MoEML’s 2012 SSHRC Insight Grant.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Author of abstract

-

Conceptor

-

Encoder

-

Markup editor

-

Name Encoder

-

Post-conversion and Markup Editor

-

Post-conversion processing and markup correction

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

Contributions by this author

Martin D. Holmes is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Martin D. Holmes is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Amble

Dramatic character in Philip Massinger’s A New Way to Pay Old Debts.Amble is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Lording Barry is mentioned in the following documents:

Lording Barry authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Barry, Lording. Ram-Alley: Or Merrie-Trickes. London: Printed by G. Eld. for Robert Wilson, 1611. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Richard Brome is mentioned in the following documents:

Richard Brome authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Brome, Richard. The Demoiselle, or the New Ordinary. London: T[homas] R[oycroft] for Richard Marriot, and Thomas Dring, 1653. Remediated by Richard Brome Online.

-

Brome, Richard. A Mad Couple Well-Match’d. Five New Playes. London: Humphrey Moseley, Richard Marriot, and Thomas Dring, 1653. Sig. A5v-H2r. Remediated by Richard Brome Online.

-

Henry Chettle is mentioned in the following documents:

Henry Chettle authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Day, John [and Henry Chettle]. The Blind-beggar of Bednal Green. London: R. Pollard and Tho. Dring, 1659. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. Ed. Vittorio Gabrieli and Giorgio Melchiori. Revels Plays. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1990. Print.

-

John Day is mentioned in the following documents:

John Day authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Day, John [and Henry Chettle]. The Blind-beggar of Bednal Green. London: R. Pollard and Tho. Dring, 1659. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Henry VIII

Henry This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 8VIII King of England King of Ireland

(b. 28 June 1491, d. 28 January 1547)King of England and Ireland 1509-1547.Henry VIII is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Ben Jonson is mentioned in the following documents:

Ben Jonson authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Chapman, George, Ben Jonson, and John Marston. Eastward Ho! Ed. R.W. Van Fossen. New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Print.

-

Dekker, Thomas, Stephen Harrison, Ben Jonson, and Thomas Middleton. The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment of King James through the City of London, 15 March 1604, with the Arches of Triumph. Ed. R. Malcolm Smuts. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 219–79.

-

Gifford, William, ed. The Works of Ben Jonson. By Ben Jonson. Vol. 1. London: Nichol, 1816. Remediated by Internet Archive.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Alchemist. London: New Mermaids, 1991. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Bartholomew Fair. Ed. E.A. Horsman. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1979. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Bartholomew Fair. Ed. Suzanne Gossett, based on The Revels Plays edition ed. E.A. Horsman. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2000. Revels Student Editions. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. B. Ion: his part of King Iames his royall and magnificent entertainement through his honorable cittie of London, Thurseday the 15. of March. 1603 so much as was presented in the first and last of their triumphall arch’s. London, 1604. STC 14756. EEBO.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Complete Poetry of Ben Jonson. Ed. William B. Hunter. Stuart Edtions. New York: New YorkUP, 1963.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Devil is an Ass. Ed. Peter Happé. Manchester and New York: Manchester UP, 1996. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Epicene. Ed. Richard Dutton. Revels Plays. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2004. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Every Man Out of His Humour. Ed. Helen Ostovich. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2001. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. The First, of Blacknesse, Personated at the Court, at White-hall, on the Twelfth Night, 1605. The Characters of Two Royall Masques: The One of Blacknesse, the Other of Beautie. Personated by the Most Magnificent of Queenes Anne Queene of Great Britaine, &c. with her Honorable Ladyes, 1605 and 1608 at White-hall. London : For Thomas Thorp, and are to be Sold at the Signe of the Tigers Head in Paules Church-yard, 1608. Sig. A3r-C2r. STC 14761. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Jonson, Ben. Oberon, The Faery Prince. The Workes of Benjamin Jonson. Vol. 1. London: Will Stansby, 1616. Sig. 4N2r-2N6r. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Staple of Newes. The Works. Vol. 2. London: Printed by I.B. for Robert Allot, 1631. Sig. 2A1r-2J2v. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Staple of News. Ed. Anthony Parr. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben.

To Penshurst.

The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt, Carol T. Christ, Alfred David, Barbara K. Lewalski, Lawrence Lipking, George M. Logan, Deidre Shauna Lynch, Katharine Eisaman Maus, James Noggle, Jahan Ramazani, Catherine Robson, James Simpson, Jon Stallworthy, Jack Stillinger, and M. H. Abrams. 9th ed. Vol. B. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2012. 1547. -

Jonson, Ben. The vvorkes of Beniamin Ionson. Containing these playes, viz. 1 Bartholomew Fayre. 2 The staple of newes. 3 The Divell is an asse. London, 1641. EEBO. Reprint. Subscr. STC 14754.

-

Lickfinger

Dramatic haracter in Ben Jonson’s The Staple of News.Lickfinger is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Marrall

Dramatic character in Philip Massinger’s A New Way to Pay Old Debts.Marrall is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Marston is mentioned in the following documents:

John Marston authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Chapman, George, Ben Jonson, and John Marston. Eastward Ho! Ed. R.W. Van Fossen. New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Print.

-

Philip Massinger is mentioned in the following documents:

Philip Massinger authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Massinger, Philip.

The City Madam.

The Plays and Poems of Philip Massinger. Ed. Philip Edwards and Colin Gibson. Oxford: Claredon, 1976. Print. -

Massinger, Philip. A New Way to Pay Old Debts. London: Printed by E[lizabeth] P[urslowe] for Henry Seyle, 1633. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Thomas Nashe is mentioned in the following documents:

Thomas Nashe authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Nashe, Thomas. Pierce Penileſſe His Svpplication to the Diuell. London, 1592. STC 18373. Reprint. EEBO. Web. Subscr. EEBO.

-

Nashe, Thomas. The returne of the renowned Caualiero Pasquill of England from the other side the seas, and his meeting with Marforius at London vpon the Royall Exchange where they encounter with a little houshold talke of Martin and Martinisme, discouering the scabbe that is bredde in England, and conferring together about the speedie dispersing of the golden legende of the liues of saints. London, 1589. STC 19457.3. Reprint. Early English Books Online. Web.

-

Nashe, Thomas. A Wonderfull Strange and Miraculous Astrologicall Prognostication for this Yeere 1591. London: Thomas Scarlet, 1591. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

John Stow

(b. between 1524 and 1525, d. 1605)Historian and author of A Survey of London. Husband of Elizabeth Stow.John Stow is mentioned in the following documents:

John Stow authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Blome, Richard.

Aldersgate Ward and St. Martins le Grand Liberty Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. M3r and sig. M4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Aldgate Ward with its Division into Parishes. Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections & Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H3r and sig. H4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Billingsgate Ward and Bridge Ward Within with it’s Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. Y2r and sig. Y3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Bishopsgate-street Ward. Taken from the Last Survey and Corrected.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. N1r and sig. N2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Bread Street Ward and Cardwainter Ward with its Division into Parishes Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. B3r and sig. B4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Broad Street Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections and Additions, & Cornhill Ward with its Divisions into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, &c.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. P2r and sig. P3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Cheape Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig.D1r and sig. D2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Coleman Street Ward and Bashishaw Ward Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. G2r and sig. G3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Cow Cross being St Sepulchers Parish Without and the Charterhouse.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H2v and sig. H3r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Creplegate Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, with Additions, and Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. I3r and sig. I4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Farrington Ward Without, with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections & Amendments.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. 2F3r and sig. 2F4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Lambeth and Christ Church Parish Southwark. Taken from ye last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. Z1r and sig. Z2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Langborne Ward with its Division into Parishes. Corrected from the Last Survey. & Candlewick Ward with its Division into Parishes. Corrected from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. U3r and sig. U4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Map of St. Gilles’s Cripple Gate. Without. With Large Additions and Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H2v and sig. H3r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Map of the Parish of St. Dunstans Stepney, als. Stebunheath Divided into Hamlets.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. F3r and sig. F4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Map of the Parish of St Mary White Chappel and a Map of the Parish of St Katherines by the Tower.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. F2r and sig. F3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of Lime Street Ward. Taken from ye Last Surveys & Corrected.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. M1r and sig. M2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of St. Andrews Holborn Parish as well Within the Liberty as Without.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. 2I1r and sig. 2I2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parishes of St. Clements Danes, St. Mary Savoy; with the Rolls Liberty and Lincolns Inn, Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig.O4v and sig. O1r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St. Anns. Taken from the last Survey, with Correction, and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. L2v and sig. L3r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St. Giles’s in the Fields Taken from the Last Servey, with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. K1v and sig. K2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Margarets Westminster Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig.H3v and sig. H4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Martins in the Fields Taken from ye Last Survey with Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. I1v and sig. I2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Pauls Covent Garden Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. L3v and sig. L4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Saviours Southwark and St Georges taken from ye last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. D1r and sig.D2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

The Parish of St. James Clerkenwell taken from ye last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H3v and sig. H4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

The Parish of St. James’s, Westminster Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. K4v and sig. L1r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

The Parish of St Johns Wapping. The Parish of St Paul Shadwell.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. E2r and sig. E3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Portsoken Ward being Part of the Parish of St. Buttolphs Aldgate, taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. B1v and sig. B2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Queen Hith Ward and Vintry Ward with their Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. 2C4r and sig. 2D1v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Shoreditch Norton Folgate, and Crepplegate Without Taken from ye Last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. G1r and sig. G2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Spitt Fields and Plans Adjacent Taken from Last Survey with Locations.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. F4r and sig. G1v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

St. Olave and St. Mary Magdalens Bermondsey Southwark Taken from ye last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. C2r and sig.C3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Tower Street Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. E2r and sig. E3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Walbrook Ward and Dowgate Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Surveys.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. 2B3r and sig. 2B4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

The Wards of Farington Within and Baynards Castle with its Divisions into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. Q2r and sig. Q3v. [See more information about this map.] -

The City of London as in Q. Elizabeth’s Time.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Frontispiece. -

A Map of the Tower Liberty.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H4v and sig. I1r. [See more information about this map.] -

A New Plan of the City of London, Westminster and Southwark.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Frontispiece. -

Pearl, Valerie.

Introduction.

A Survey of London. By John Stow. Ed. H.B. Wheatley. London: Everyman’s Library, 1987. v–xii. Print. -

Pullen, John.

A Map of the Parish of St Mary Rotherhith.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. Z3r and sig. Z4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Stow, John, Anthony Munday, and Henry Holland. THE SVRVAY of LONDON: Containing, The Originall, Antiquitie, Encrease, and more Moderne Estate of the sayd Famous Citie. As also, the Rule and Gouernment thereof (both Ecclesiasticall and Temporall) from time to time. With a briefe Relation of all the memorable Monuments, and other especiall Obseruations, both in and about the same CITIE. Written in the yeere 1598. by Iohn Stow, Citizen of London. Since then, continued, corrected and much enlarged, with many rare and worthy Notes, both of Venerable Antiquity, and later memorie; such, as were neuer published before this present yeere 1618. London: George Purslowe, 1618. STC 23344. Yale University Library copy Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Stow, John, Anthony Munday, and Humphrey Dyson. THE SURVEY OF LONDON: CONTAINING The Original, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of that City, Methodically set down. With a Memorial of those famouser Acts of Charity, which for publick and Pious Vses have been bestowed by many Worshipfull Citizens and Benefactors. As also all the Ancient and Modern Monuments erected in the Churches, not only of those two famous Cities, LONDON and WESTMINSTER, but (now newly added) Four miles compass. Begun first by the pains and industry of John Stow, in the year 1598. Afterwards inlarged by the care and diligence of A.M. in the year 1618. And now compleatly finished by the study &labour of A.M., H.D. and others, this present year 1633. Whereunto, besides many Additions (as appears by the Contents) are annexed divers Alphabetical Tables, especially two, The first, an index of Things. The second, a Concordance of Names. London: Printed for Nicholas Bourne, 1633. STC 23345.5. Harvard University Library copy Reprint. Early English Books Online. Web.

-

Stow, John. The chronicles of England from Brute vnto this present yeare of Christ. 1580. Collected by Iohn Stow citizen of London. London, 1580. Rpt. EEBO. Web.

-

Stow, John. A Summarie of the Chronicles of England. Diligently Collected, Abridged, & Continued vnto this Present Yeere of Christ, 1598. London: Imprinted by Richard Bradocke, 1598. Rpt. EEBO. Web.

-

Stow, John. A suruay of London· Conteyning the originall, antiquity, increase, moderne estate, and description of that city, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow citizen of London. Since by the same author increased, with diuers rare notes of antiquity, and published in the yeare, 1603. Also an apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that citie, the greatnesse thereof. VVith an appendix, contayning in Latine Libellum de situ & nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. London: John Windet, 1603. STC 23343. U of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign Campus) copy Reprint. Early English Books Online. Web.

-

Stow, John, The survey of London contayning the originall, increase, moderne estate, and government of that city, methodically set downe. With a memoriall of those famouser acts of charity, which for publicke and pious vses have beene bestowed by many worshipfull citizens and benefactors. As also all the ancient and moderne monuments erected in the churches, not onely of those two famous cities, London and Westminster, but (now newly added) foure miles compasse. Begunne first by the paines and industry of Iohn Stovv, in the yeere 1598. Afterwards inlarged by the care and diligence of A.M. in the yeere 1618. And now completely finished by the study and labour of A.M. H.D. and others, this present yeere 1633. Whereunto, besides many additions (as appeares by the contents) are annexed divers alphabeticall tables; especially two: the first, an index of things. The second, a concordance of names. London: Printed by Elizabeth Purslovv for Nicholas Bourne, 1633. STC 23345. U of Victoria copy.

-

Stow, John, The survey of London contayning the originall, increase, moderne estate, and government of that city, methodically set downe. With a memoriall of those famouser acts of charity, which for publicke and pious vses have beene bestowed by many worshipfull citizens and benefactors. As also all the ancient and moderne monuments erected in the churches, not onely of those two famous cities, London and Westminster, but (now newly added) foure miles compasse. Begunne first by the paines and industry of Iohn Stovv, in the yeere 1598. Afterwards inlarged by the care and diligence of A.M. in the yeere 1618. And now completely finished by the study and labour of A.M. H.D. and others, this present yeere 1633. Whereunto, besides many additions (as appeares by the contents) are annexed divers alphabeticall tables; especially two: the first, an index of things. The second, a concordance of names. London: Printed by Elizabeth Purslovv [i.e., Purslow] for Nicholas Bourne, 1633. STC 23345. British Library copy Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Stow, John. A Survey of London. Reprinted from the Text of 1603. Ed. Charles Lethbridge Kingsford. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1908. Remediated by British History Online.

-

Stow, John. A Survey of London. Reprinted from the Text of 1603. Ed. Charles Lethbridge Kingsford. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1908. Remediated by British History Online. [Kingsford edition, courtesy of The Centre for Metropolitan History. Articles written 2011 or later cite from this searchable transcription.]

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ &nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. 23341. Transcribed by EEBO-TCP.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ & nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. Ed. Janelle Jenstad and the MoEML Team. MoEML. Transcribed. Web.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ &nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. Folger Shakespeare Library.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ &nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. London: John Windet for John Wolfe, 1598. STC 23341. Huntington Library copy. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Coteyning the Originall, Antiquity, Increaſe, Moderne eſtate, and deſcription of that City, written in the yeare 1598, by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Since by the ſame Author increaſed with diuers rare notes of Antiquity, and publiſhed in the yeare, 1603. Alſo an Apologie (or defence) againſt the opinion of ſome men, concerning that Citie, the greatneſſe thereof. With an Appendix, contayning in Latine Libellum de ſitu & nobilitae Londini: Writen by William Fitzſtephen, in the raigne of Henry the ſecond. London: John Windet, 1603. U of Victoria copy. Print.

-

Strype, John, John Stow, Anthony Munday, and Humphrey Dyson. A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster. Vol. 2. London, 1720. Remediated by The Making of the Modern World.

-

Strype, John, John Stow. A SURVEY OF THE CITIES OF LONDON and WESTMINSTER, And the Borough of SOUTHWARK. CONTAINING The Original, Antiquity, Increase, present State and Government of those CITIES. Written at first in the Year 1698, By John Stow, Citizen and Native of London. Corrected, Improved, and very much Enlarged, in the Year 1720, By JOHN STRYPE, M.A. A NATIVE ALSO OF THE SAID CITY. The Survey and History brought down to the present Time BY CAREFUL HANDS. Illustrated with exact Maps of the City and Suburbs, and of all the Wards; and, likewise, of the Out-Parishes of London and Westminster, and the Country ten Miles round London. Together with many fair Draughts of the most Eminent Buildings. The Life of the Author, written by Mr. Strype, is prefixed; And, at the End is added, an APPENDIX Of certain Tracts, Discourses, and Remarks on the State of the City of London. 6th ed. 2 vols. London: Printed for W. Innys and J. Richardson, J. and P. Knapton, and S. Birt, R. Ware, T. and T. Longman, and seven others, 1754–55. ESTC T150145.

-

Strype, John, John Stow. A survey of the cities of London and Westminster: containing the original, antiquity, increase, modern estate and government of those cities. Written at first in the year MDXCVIII. By John Stow, citizen and native of London. Since reprinted and augmented by A.M. H.D. and other. Now lastly, corrected, improved, and very much enlarged: and the survey and history brought down from the year 1633, (being near fourscore years since it was last printed) to the present time; by John Strype, M.A. a native also of the said city. Illustrated with exact maps of the city and suburbs, and of all the wards; and likewise of the out-parishes of London and Westminster: together with many other fair draughts of the more eminent and publick edifices and monuments. In six books. To which is prefixed, the life of the author, writ by the editor. At the end is added, an appendiz of certain tracts, discourses and remarks, concerning the state of the city of London. Together with a perambulation, or circuit-walk four or five miles round about London, to the parish churches: describing the monuments of the dead there interred: with other antiquities observable in those places. And concluding with a second appendix, as a supply and review: and a large index of the whole work. 2 vols. London : Printed for A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. ESTC T48975.

-

The Tower and St. Catherins Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H4v and sig. I1r. [See more information about this map.] -

Wheatley, Henry Benjamin.

Introduction.

A Survey of London. 1603. By John Stow. London: J.M. Dent and Sons, 1912. Print.

-

Bumpsey

Dramatic caracter in Richard Brome’s The Damoiselle.Bumpsey is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Careless

Dramatic character in Richard Brome’s A Mad Couple Well-Match’d.Careless is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Robert Harris

Brewery owner. Purchased the Star and Ram Inn from King Henry VIII, which later became the site of Ram Alley.Robert Harris is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thomas Shadwell is mentioned in the following documents:

Thomas Shadwell authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Shadwell, Thomas. The Squire of Alsatia. London: Printed for James Knapton, at the Queen’s Head in St. Paul’s Churchyard, 1688. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Margaret Lilly

Resident of Ram Alley charged with harbouring foreigners.Margaret Lilly is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Simon Dominico

French foreigner who resided in the residence of Margaret Lilly in Ram Alley.Simon Dominico is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Throat

Dramatic character in Lording Barry’s Ram Alley.Throat is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Richard Head is mentioned in the following documents:

Richard Head authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Head, Richard. The Floating Island, or a New Discovery. London: Published by Franck Careless [i.e., Richard Head], 1673. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Whipping Tom

Nickname given to an unidentified sexual predator who frequented the alleys around Fleet Street in 1681.Whipping Tom is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Timothy How

Resident of Ram Alley. Described in a 1630 wardmote register as annyoing the judges of Serjeants Inn with the stench of his tobacco.Timothy How is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Humphrey Fenne

Possible resident of Ram Alley. Described in a 1630 wardmote register as annyoing the judges of Serjeants Inn with the stench of his tobacco.Humphrey Fenne is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Barker

Shopkeeper in Ram Alley. Charged with selling tabacco and alcohol throughout the night without a license. Not to be confused with John Barker.John Barker is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Timothy Louse

Shopkeeper in Ram Alley. Charged with selling tabacco and alcohol throughout the night without a license.Timothy Louse is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Canby is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Tom Strowd is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Swash is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Captain Pod

Pod

Well-known exhibitor of puppet shows. Alluded to in John Day and Henry Chettle’s The Blind Beggar of Bethnal Green.Captain Pod is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Ms. Rump

Rump

Resident of Ram Alley. Alluded to in John Day and Henry Chettle’s The Blind Beggar of Bethnal Green.Ms. Rump is mentioned in the following documents:

Locations

-

Fleet Street

Fleet Street runs east-west from Temple Bar to Fleet Hill (Ludgate Hill), and is named for the Fleet River. The road has existed since at least the 12th century (Sugden 195) and known since the 14th century as Fleet Street (Beresford 26). It was the location of numerous taverns including the Mitre and the Star and the Ram.Fleet Street is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Fetter Lane

Fetter Lane ran north-south between Holborn Street and Fleet Street, in the ward of Farringdon Without, past the east side of the church of Saint Dunstan’s in the West. Stow consistently calls this streetFewtars Lane,

Fewter Lane,

orFewters Lane

(2:21, 2:22), and claimed that it wasso called of Fewters (or idle people) lying there

(2:39).Fetter Lane is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Inner Temple

Inner Temple was one of the four Inns of CourtInner Temple is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Serjeants’ Inn (Fleet Street) is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Mitre Tavern is mentioned in the following documents:

-

The Star and the Ram is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Hare House

According to Walter George Bell, Hare House was a property in Ram Alley left by John Bowser and Humphrey Street in 1584upon trust for 1,000 years, that every Sunday thirteen pennyworth of bread should be given to thirteen poor people of the parish after service in St. Dunstan’s church

(Bell 296).Hare House is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Whitefriars

This page points to the district known as Whitefriars. For the theatre, see Whitefriars Theatre.Whitefriars is mentioned in the following documents:

-

London is mentioned in the following documents:

-

The Maidhead (Ram Alley)

Edward H. Sugden describes the Maidenhead tavern in Ram Alley asthe worst of all dens of infamy in that notorious court

(Sugden 328).The Maidhead (Ram Alley) is mentioned in the following documents:

-

St. Dunstan in the West (Parish) is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Whitefriars Theatre

One of the lesser known halls or private playhouses of Renaissance London, the Whitefriars, was home to two different boy playing companies, each of which operated under several different names. Whitefriars produced many famous boy actors, some of whom later went on to greater fame in adult companies. At the Whitefriars playhouse in 1607–1608, the Children of the King’s Revels catered to a homogenous audience with a particular taste for homoerotic puns and situations, which resulted in a small but significant body of plays that are markedly different from those written for the amphitheatres and even for other hall playhouses.Whitefriars Theatre is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Fuller Rents is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Milford Lane is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Middle Temple

Middle Temple was one of the four Inns of CourtMiddle Temple is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Pie Corner is mentioned in the following documents:

Organizations

-

The King’s Revels Children

The King’s Revels Children (also known as the Children of the King’s Revels) was a playing company of boy actors in early modern London. It appears to have emerged in early 1607, and its history is closely linked to the Blackfriars Boys after 1609. See Gurr 361-62, 365.This organization is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Knights Hospitallers

Roman Catholic military order that originated in the Mediterranean region during the eleventh century. Also known as the Order of the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem, Order of the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem. (TL)This organization is mentioned in the following documents:

Glossary

-

inn of court

Institution where law students and junior barristers were housed and educated. (TL)This term is tagged in the following documents:

-

inn of chancery