Fenchurch Street

Location

Fenchurch Street (often called Fennieabout) runs east-west from

the pump on Aldgate High Street to Gracechurch Street in Langbourne Ward, crossing Mark Lane,

Mincing Lane, and Rodd

Lane along the way. Fenchurch traverses

Aldgate Ward and Limestreet Ward. Stow observes that the street

is of Ealdgate warde till ye come to Culuar Alley, on the west side of Ironmongers Hall where sometime was a lane which went out of Fenchurchstreete to the midst of Limestreete(Stow 200).

Name and Etymology

Stow lists many possible origins for the name of

the street, suggesting that

Fenchurch Street took that name of a fenny or moorish ground, so made by means, of this borne which passed through it Gap in transcription. Reason: Editorial omission for reasons of length or relevance. Use only in quotations in born-digital documents.[…] yet others be of the opinion that it took the name of Foenum, that is, hey solde there, just as Grasse Street tooke the name of grass or hearbes there solde(200). The eponymous

churchwas St. Gabriel Fenchurch, located on the north side of the street between Rodd Lane and Mincing Lane. The church burned down in the Great Fire of 1666, but the street’s name endured. The street is ambiguously labelled on the Agas map, with the name Fenchurch appearing on the street directly below the church building so that the label could refer to either the church or the street. Prockter and Taylor, however, label the street Fenchurch Street (13), as does Richard Blome in his 1720 map of Aldgate Ward with its Division into Parishes (British Library) and Jacob Ilive’s 1739 A Plan of the Ward of Aldgate (rpt. in Hyde 34). Eilert Ekwall offers several other common spellings of the name, including Fancherche and Fanchurche (96).

History

Ralph Tresswell’s 1612 survey of

the area provides a detailed view of Fenchurch’s west side at its intersection with Philpot Lane. The property shown, acquired by John Lute in 1541, came into the

possession of the Clothworkers’ Company upon his

death in 1585 (Schofield 70). This acquisition added to the Company’s already

considerable landholdings (see Billiter Lane), and

speaks to the immense wealth and power of this

livery company. The Clothworkers eventually came to own almost half of

Fenchurch Street and profited from renting

properties as dwellings and storefronts. The shops along Fenchurch would have had highly visibile to people entering the city

through Aldgate, one of the primary entry points

into the city. Archaeological excavations have found evidence of rubbish pits

likely associated with the processing of animal carcasses for furs and hides

(LAARC

Site Record FEU008). These findings suggest that Fenchurch was home to a wealth of commercial activities including production, trading, and waste disposal. From 1556 to 1557, the Clothworkers’ Company invested funds in the revitalization of the neighbourhood, hiring a carpenter named Revell to spearhead the construction project. This rebuilding led to an increased demand for houses on Fenchurch Street, raising their rental value. A house near Billiter Lane that cost fifty-eight shillings (almost three pounds) per annum prior to 1558 cost eight pounds after the renovations (Schofield 74).

Significance

Fenchurch Street was home to several famous

landmarks, including the King’s Head Tavern, where

the then-Princess Elizabeth is said to have

partaken in

pork and peasafter her sister, Mary I, released her from the Tower of London in May of 1554 (Weinreb, Hibbert, Keay, and Keay 288). Fenchurch was also the location of the town residence known as Northumberland House, where the earl of Northumberland would stay when visiting London. The gardens lining these houses were later converted to bowling alleys open to the public. Fenchurch street was also the site of Denmark House, the residence of the first Russian ambassador to England. The arrival of the ambassador in 1557 was recorded by Henry Machyn in his diary entry for 27 February of that year:

[a]n ambassador came to London from the emperour of Cattay, Moscouie, and Russe lande: who was honorably met and receyued at Totham by the merchantes venturers of London, rydyng in veluet coates and chayues of gold, and by them conducted to the barres at Smithfield, and there receiued by the lorde maior of London, with the aldermen and sheriffes: and so by the lorde Maior, aldermen and merchant venturers, conueyed thorough the Citie, vnto maister Dimokes place in Fanchurch strete. 1 (Machyn 1557-02-27)Fenchurch Street was on the royal processional route through the city, toured by monarchs on the day before their coronations. These events,

rich in pageantry and cultural significance,allowed commoners to

welcome [their new ruler] with gifts and pageants(Butler). Surviving eyewitness accounts offer evidence of Fenchurch’s residents preparing for a royal visit. Machyn names Fenchurch Street as one of the primary sites where London’s citizens hung decorations to celebrate the upcoming coronation of Mary I:

the citizens began to adorn the city against the Queen’s coronation; to hang the streets, and prepare pageants at Fan Church and Grace Church(1553-09-12).2 Then, when she arrived, Mary travelled from the

Tower through London riding in a chariot looking gorgeously unto Westminster. By the way at Fenchurch a goodly pageant with four giants and with goodly speeches Gap in transcription. Reason: Editorial omission for reasons of length or relevance. Use only in quotations in born-digital documents.[…](1553-09-30)3. That Fenchurch Street was part of the royal processional route is a testament to its importance as a major thoroughfare.

Literary References

Five years after Mary’s entry, Richard Mulcaster describes an identical scene in The Queen’s Majesty’s

Passage, this time with Elizabeth

I riding triumphantly through the streets. Mulcaster served in Elizabeth’s first

parliament as representative of Carlisle. He received forty shillings in payment

for the account of the pageant (Barker). He records the wonder upon seeing her

[pass] from the Towre tyll she came to Fanchurche, the people on eche syde ioyoussye beholding the viewe of so gracious a Ladie their quene, and her grace no lesse gladlye notyng and obseruying the same. Here unto Fanchurch was erected a scaffold richely furnished, wheron stode a noyes of instrumentes, and a child in costly apparel, which was appointed to welcome the quenes maiestie in ye hole cities behalfe. (Mulcaster)

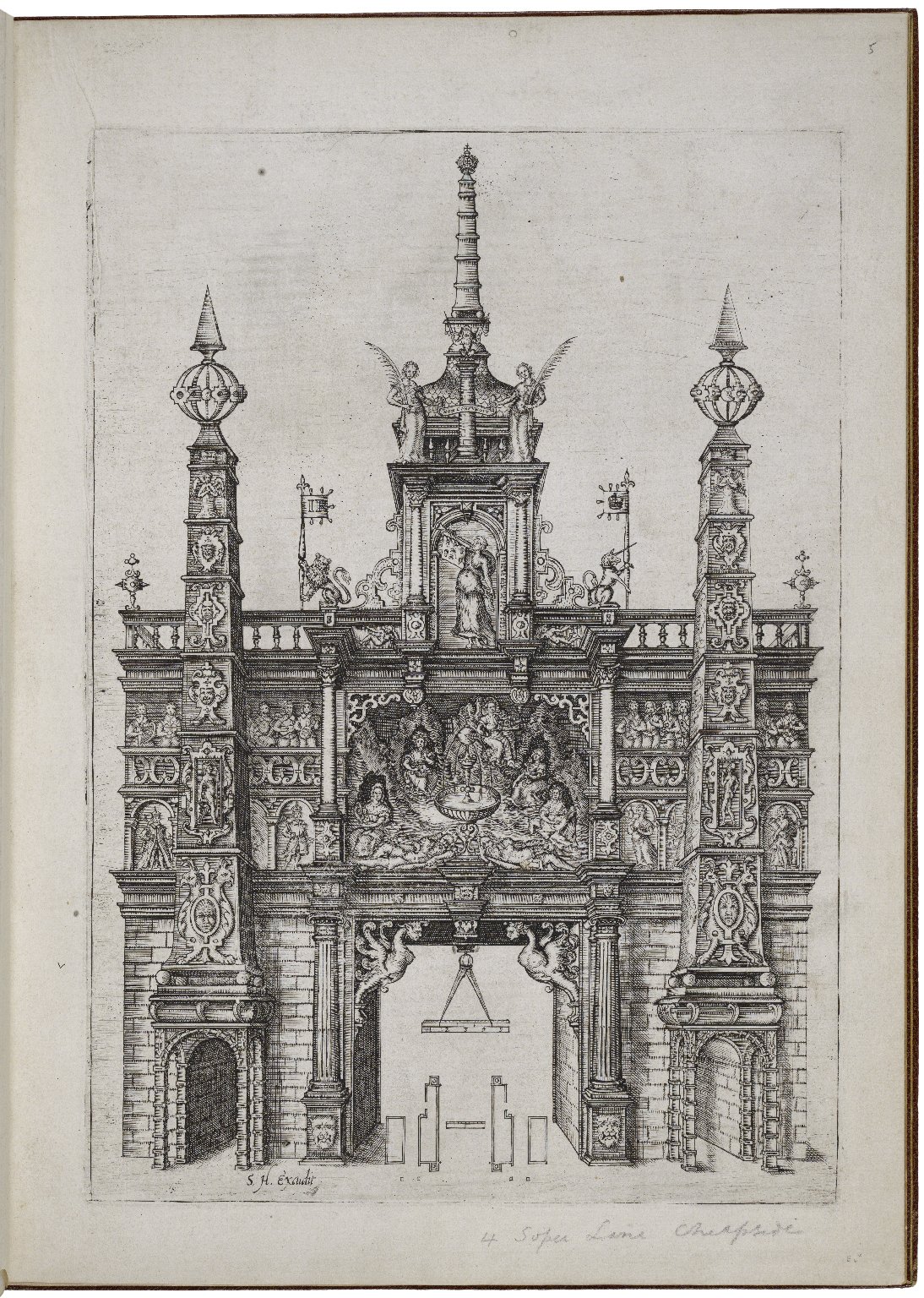

As Thomas Dekker records in The

Magnificent Entertainment, Fenchurch

was the site of the first triumphal arch through which King

James I passed when he visited in 1604:

from thence stept presently into his Citie of London, which for the time might worthily borrow the name of his Court Royall: His passage alongst that Court, offering it selfe for more State through seuen Gates, of which the first was erected at Fanchurch(sig. B4r). This gate refers to one of seven Arches of Triumph conceived and designed by Stephen Harrison in collaboration with Thomas Dekker and Ben Jonson (Bergeron 445; Chalfant 74). Carved atop Fenchurch’s arch was London itself, populated with a series of allegorical figures attesting to the city’s many virtues (see reproduction of Harrison’s Londinium arch in Chalfant 75; see also the page image in Harrison). Harrison underscored the rich opulence in his design with a series of Latin phrases, carved just above the entrance, paying tribute to both the splendour of the Lord and the British king—in that order. The first phrase is a quotation from the first-century poet Martial:

Par domus haec coelo sed minor est domino4 (75), followed by a phrase of reading

Camera Regia5 written in

a lesse and different character(Mardock 32). James Mardock notes in Our Scene is Londonthat while the praise of both

city and king are evident,the order and appearance of the two phrases—as well as their proximity to the

royal reader’s eye—suggests a hierarchy

with the royal domino greater than the civic domus(Mardock 32). Gilbert Dugdale marvels at the workmanship and painstaking detail of this arch in A Time Triumphant, writing

such a show of Gap in transcription. Reason: Editorial omission for reasons of length or relevance. Use only in quotations in born-digital documents.[…] glorie as I neuer saw the like Gap in transcription. Reason: Editorial omission for reasons of length or relevance. Use only in quotations in born-digital documents.[…] The Cittie of London very rarely artificially made, where no church, nor house of note but your eye might easily find out(sig. B2r).

The few dramatic references to Fenchurch Street

occur in city comedies, often providing information about the origins of a

character rather than overtly participating in the action of the

play. For example, the second title of

Thomas Heywood’s

1607 comedy The Fair Maid of the Exchange

is The Pleasant Humours of the Cripple of Fanchurch,

but the play contains no further reference to the street

. The subtitle provides

the central male character with depth by establishing him as a disadvantaged

character living (or growing up) in an affluent

neighbourhood. A

more sustained mapping of Fenchurch Street occurs

in William Haughton’s

1598

Englishmen for my Money. This city comedy calls upon

the audience’s knowledge of the streets and features of the city. As Jean Howard

observes of this play,

[t]he acme of the play’s geographical localism Gap in transcription. Reason: Editorial omission for reasons of length or relevance. Use only in quotations in born-digital documents.[…] occurs in IV.i, a scene whose humor hinges on the gap in knowledge between those who have an intimate familiarity with London’s streets and those who do not(40). Darryll Grantley argues that a

comic and nationalist capitalis created by the confusion of the play’s three foreign suitors—Alvaro, Delion, and Vandalle—when they get lost in London on their way to Crutched Friars (75), leading to an exchange between the foreign suitor Delion and the Englishman Heigham:

The play invites sympathy for, or disapproval of, the characters through the differing degrees to which characters share the London habitation of the playgoers. To the playgoer in 1598, the foreigners’ inability to locate or even pronounce London streets would have functioned as aDelWhat be name dis st., and wish be de way to Croshe-friars? 6HeighMarry, this is Fenchurch St. and the best way to Crutched Friars is to follow your nose.DelVanshe st.! How shance me come to Vanshe st.? 7

(Haughton 4.1.92-96)

hilarious marker of their unsuitability as husbands for London maids(Jenstad 112). Likewise, Alan Stewart suggests that the strangers’ deeply flawed English is an irresolvable barrier to marriage, and that any union between English and other languages is figured as

unhealthy and dangerous(71). The inherent nationalism couched in this exchange arises from the spectators’ satisfaction—at the expense of the intruder—in having a sound grasp of London’s geography and thus being a true Londoner. This geographical confusion

cedes a competitive advantage to the English suitors,who use their intimate knowledge (and as the play would argue, ownership) of the land to win the race and obtain the affection of the female characters (Grantley 75).

Subsequent History

Samuel Pepys describes Fenchurch as one of the streets most severely affected by the

Great Plague of 1665. His diary entry

on 10 June 1665 records his

great trouble, to hear that the Plague is come into the City Gap in transcription. Reason: Editorial omission for reasons of length or relevance. Use only in quotations in born-digital documents.[…] but where should it begin but in my good friend and neighbour’s, Dr. Burnett, in Fenchurch Street; which, in both points, troubles me mightily(1665-06-10). Later, on 6 August, one Mr. Battersby in Fenchurch asked Pepys

[d]o you see Dan Rawlinson’s door all shut up? Gap in transcription. Reason: Editorial omission for reasons of length or relevance. Use only in quotations in born-digital documents.[…] one of his men is now dead from the plague and his wife’s sick(1665-08-06). Rawlinson, of whom Pepys speaks fondly elsewhere in his diary, owned the Mitre Tavern in Fenchurch (Wheatley 35).

In modern London, Fenchurch Street follows the path

of early modern Fenchurch Street from Aldgate to Gracechurch. Fenchurch gives its name

to Fenchurch Street Station, the

first station to be located within the City of London(

History of Fenchurch Street Station).

Notes

- Missing characters in passage supplied by Bailey, Miller, and Moore.↑

- Missing characters supplied by Bailey, Miller, and Moore.↑

- Missing characters supplied by Bailey, Miller, and Moore↑

This house is on a par with the heavens, but less than its master

↑The King’s Chamber,

↑- Delion, a Frenchman, means to say, What be

the name of this street, and which be the way to

Crutched Friars?

↑ - Delion means

Fenchurch Street! How chance me come to Fenchurch Street?

↑

References

-

Citation

Barker, William.Mulcaster, Richard (1531/2–1611): Schoolmaster and Author.

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H.C.G. Matthew, Brian Harrison, Lawrence Goldman, and David Cannadine. Oxford UP. https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/19509.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Bergeron, David M.Harrison, Jonson and Dekker: The Magnificent Entertainment for King James I (1604).

Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 31 (1968): 445–448. doi:10.2307/750656.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Blome, Richard.Aldgate Ward with its Division into Parishes. Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections & Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H3r and sig. H4v. [See more information about this map.]This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Chalfant, Fran C. Ben Jonson’s London: A Jacobean Placename Dictionary. Athens: U of Georgia P, 1978. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Dekker, Thomas. The magnificent entertainment giuen to King James, Queene Anne his wife, and Henry Frederick the Prince, upon the day of his Majesties triumphant passage (from the Tower) through his honourable citie (and chamber) of London, being the 15. of March. 1603. As well by the English as by the strangers: with the speeches and songes, deliuered in the severall pageants. London: Printed by Thomas Creede for Thomas Man the younger, 1604. EEBO. Reprint. Subscr.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Dugdale, Gilbert. The time triumphant declaring in briefe, the arival of our soveraigne liedge Lord, King James into England, his coronation at Westminster: together with his late royal progresse, from the Towre of London throúgh the Cittie, to his Highnes manor of White Hall. Shewing also, the varieties & rarieties of al the sundry trophies or pageants, erected . . . With a rehearsall of the King and Queenes late comming to the Exchaunge in London. London, 1604. EEBO. Reprint. Subscr.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Ekwall, Eilert. Street-Names of the City of London. Oxford: Clarendon, 1965. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Grantley, Darryll. London in Early Modern English Drama: Representing the Built Environment. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Harrison, Stephen. The arch’s of triumph erected in honor of the high and mighty prince. James. the first of that name. King, of England. and the sixt of Scotland at his Majesties entrance and passage through his honorable citty & chamber of London. upon the 15th. day of march 1603. Invented and published by Stephen Harrison ioyner and architect: and graven by William Kip. London, 1613. EEBO. Reprint. Subscr.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Haughton, William. English-men for my Money: or, A pleasant Comedy, called, A Woman will haue her Will. London, 1616. EEBO. Reprint. Subscr. STC 12931.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

History of Fenchurch Street Station.

Network Rail. https://www.networkrail.co.uk/feeds/history-un-earthed-ancient-clay-london-bridge-station-transformed-art/.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Howard, Jean. Theater of a City: The Places of London Comedy, 1598–1642. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 2007. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Hyde, Ralph. Ward Maps of the City of London. London: London Topographical Society, 1999. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Jenstad, Janelle.Using Early Modern Maps in Literary Studies: Views and Caveats from London.

GeoHumanities: Art, History, Text at the Edge of Place. Ed. Michael Dear, James Ketchum, Sarah Luria, and Doug Richardson. London: Routledge, 2011. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

London Archaeological Archive and Research Centre. MoLA. https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/collections/other-collection-databases-and-libraries/museum-london-archaeological-archive.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Machyn, Henry. The Diary of Henry Machyn, Citizen and Merchant-Taylor of London, From A.D. 1550 to A.D. 1563. Ed. John Gough Nichols. London, 1848. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Machyn, Henry. A London Provisioner’s Chronicle, 1550–1563, by Henry Machyn: Manuscript, Transcription, and Modernization. Ed. Richard W. Bailey, Marilyn Miller, and Colette Moore. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2006. Open. [The Map of Early Modern London cites from this edition rather than Nichols’s nineteenth-century edition. We cite by the date of the entry thus: (Machyn 1550–08–04).]This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Mardock, James. Our Scene is London: Jonson’s City and the Space of the Author. New York: Routledge, 2008. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Mulcaster, Richard. The Queen’s Majesty’s Passage. London: Printed by R. Tottill, 1559. SCN 7589.5. Ed. Jennie Butler and Janelle Jenstad. MoEML. Transcribed. Open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Pepys, Samuel. The Diary of Samuel Pepys: A New and Complete Transcription. Ed. Robert Latham and William Matthews. 11 vols. Berkeley : U of California P, 1970–1983.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Prockter, Adrian, and Robert Taylor, comps. The A to Z of Elizabethan London. London: Guildhall Library, 1979. Print. [This volume is our primary source for identifying and naming map locations.]This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Schofield, John, ed. The London Surveys of Ralph Treswell. London: London Topographical Society, 1987. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Stewart, Alan.

Renaissance Drama 35 (2006): 55–81.Euery Soyle to Mee is Naturall

: Figuring Denization in William Haughton’s English-men for My Money.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Stow, John. A Survey of London. Reprinted from the Text of 1603. Ed. Charles Lethbridge Kingsford. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1908. Remediated by British History Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Weinreb, Ben, Christopher Hibbert, Julia Keay, and John Keay. The London Encyclopaedia. 3rd ed. London: Macmillan, 2008. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Wheatley, Henry Benjamin. London, Past and Present: A Dictionary of its History, Associations, and Traditions. 3 vols. London: J. Murray, 1891. Reprinted by Detroit: Singing Tree P, 1968. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

Cite this page

MLA citation

.

Fenchurch Street.The Map of Early Modern London, edited by , U of Victoria, 26 Jun. 2020, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/FENC1.htm.

Chicago citation

.

Fenchurch Street.The Map of Early Modern London. Ed. . Victoria: University of Victoria. Accessed June 26, 2020. https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/FENC1.htm.

APA citation

2020. Fenchurch Street. In (Ed), The Map of Early Modern London. Victoria: University of Victoria. Retrieved from https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/FENC1.htm.

RIS file (for RefMan, EndNote etc.)

Provider: University of Victoria Database: The Map of Early Modern London Content: text/plain; charset="utf-8" TY - ELEC A1 - Kaufman, Noam ED - Jenstad, Janelle T1 - Fenchurch Street T2 - The Map of Early Modern London PY - 2020 DA - 2020/06/26 CY - Victoria PB - University of Victoria LA - English UR - https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/FENC1.htm UR - https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/xml/standalone/FENC1.xml ER -

RefWorks

RT Web Page SR Electronic(1) A1 Kaufman, Noam A6 Jenstad, Janelle T1 Fenchurch Street T2 The Map of Early Modern London WP 2020 FD 2020/06/26 RD 2020/06/26 PP Victoria PB University of Victoria LA English OL English LK https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/FENC1.htm

TEI citation

<bibl type="mla"><author><name ref="#KAUF1"><surname>Kaufman</surname>, <forename>Noam</forename></name></author>.

<title level="a">Fenchurch Street</title>. <title level="m">The Map of Early Modern

London</title>, edited by <editor><name ref="#JENS1"><forename>Janelle</forename>

<surname>Jenstad</surname></name></editor>, <publisher>U of Victoria</publisher>,

<date when="2020-06-26">26 Jun. 2020</date>, <ref target="https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/FENC1.htm">mapoflondon.uvic.ca/FENC1.htm</ref>.</bibl>

Personography

-

Joey Takeda

JT

Programmer, 2018-present. Junior Programmer, 2015-2017. Research Assistant, 2014-2017. Joey Takeda was a graduate student at the University of British Columbia in the Department of English (Science and Technology research stream). He completed his BA honours in English (with a minor in Women’s Studies) at the University of Victoria in 2016. His primary research interests included diasporic and indigenous Canadian and American literature, critical theory, cultural studies, and the digital humanities.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Introduction

-

Author of Stub

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Copy Editor and Revisor

-

Data Manager

-

Date Encoder

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Bibliography)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Agas)

-

Junior Programmer

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Encoder

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Post-conversion processing and markup correction

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Second Author

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Editor

Contributions by this author

Joey Takeda is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Joey Takeda is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Tye Landels-Gruenewald

TLG

Data Manager, 2015-2016. Research Assistant, 2013-2015. Tye completed his undergraduate honours degree in English at the University of Victoria in 2015.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

MoEML Researcher

-

Name Encoder

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

Contributions by this author

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Cameron Butt

CB

Research Assistant, 2012–2013. Cameron Butt completed his undergraduate honours degree in English at the University of Victoria in 2013. He minored in French and has a keen interest in Shakespeare, film, media studies, popular culture, and the geohumanities.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Conceptor

-

Contributing Author

-

Copy Editor

-

Creator

-

Data Manager

-

Encoder

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Transcriber

Contributions by this author

Cameron Butt is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Cameron Butt is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Noam Kaufman

NK

Research Assistant, 2012-2013. Noam Kaufman completed his Honours BA in English Literature at York University’s bilingual Glendon campus, graduating with first class standing in the spring of 2012. He was an MA student specializing in Renaissance drama, and researched early modern London’s historic cast of characters and neighbourhoods, both real and fictional.Roles played in the project

-

Annotator

-

Author

-

Encoder

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Transcriber

Contributions by this author

Noam Kaufman is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Noam Kaufman is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kim McLean-Fiander

KMF

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach, 2015–present. Associate Project Director, 2015–present. Assistant Project Director, 2013-2014. MoEML Research Fellow, 2013. Kim McLean-Fiander comes to The Map of Early Modern London from the Cultures of Knowledge digital humanities project at the University of Oxford, where she was the editor of Early Modern Letters Online, an open-access union catalogue and editorial interface for correspondence from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. She is currently Co-Director of a sister project to EMLO called Women’s Early Modern Letters Online (WEMLO). In the past, she held an internship with the curator of manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library, completed a doctorate at Oxford on paratext and early modern women writers, and worked a number of years for the Bodleian Libraries and as a freelance editor. She has a passion for rare books and manuscripts as social and material artifacts, and is interested in the development of digital resources that will improve access to these materials while ensuring their ongoing preservation and conservation. An avid traveler, Kim has always loved both London and maps, and so is particularly delighted to be able to bring her early modern scholarly expertise to bear on the MoEML project.Roles played in the project

-

Associate Project Director

-

Author

-

Author of MoEML Introduction

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Contributor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Contributor

-

Data Manager

-

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (People)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Managing Editor

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Research Fellow

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Proofreader

-

Second Author

-

Secondary Author

-

Secondary Editor

-

Toponymist

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Kim McLean-Fiander is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Kim McLean-Fiander is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Janelle Jenstad

JJ

Janelle Jenstad is Associate Professor of English at the University of Victoria, Director of The Map of Early Modern London, and PI of Linked Early Modern Drama Online. She has taught at Queen’s University, the Summer Academy at the Stratford Festival, the University of Windsor, and the University of Victoria. With Jennifer Roberts-Smith and Mark Kaethler, she co-edited Shakespeare’s Language in Digital Media (Routledge). She has prepared a documentary edition of John Stow’s A Survey of London (1598 text) for MoEML and is currently editing The Merchant of Venice (with Stephen Wittek) and Heywood’s 2 If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody for DRE. Her articles have appeared in Digital Humanities Quarterly, Renaissance and Reformation,Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Early Modern Literary Studies, Elizabethan Theatre, Shakespeare Bulletin: A Journal of Performance Criticism, and The Silver Society Journal. Her book chapters have appeared (or will appear) in Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society (Brill, 2004), Shakespeare, Language and the Stage, The Fifth Wall: Approaches to Shakespeare from Criticism, Performance and Theatre Studies (Arden/Thomson Learning, 2005), Approaches to Teaching Othello (Modern Language Association, 2005), Performing Maternity in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2007), New Directions in the Geohumanities: Art, Text, and History at the Edge of Place (Routledge, 2011), Early Modern Studies and the Digital Turn (Iter, 2016), Teaching Early Modern English Literature from the Archives (MLA, 2015), Placing Names: Enriching and Integrating Gazetteers (Indiana, 2016), Making Things and Drawing Boundaries (Minnesota, 2017), and Rethinking Shakespeare’s Source Study: Audiences, Authors, and Digital Technologies (Routledge, 2018).Roles played in the project

-

Annotator

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Stub

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

Author of Textual Introduction

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Copyeditor

-

Course Instructor

-

Course Supervisor

-

Course supervisor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Structure and Toponyms)

-

Final Markup Editor

-

GIS Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Modern)

-

Geographical Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Main Transcriber

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Project Director

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Name Encoder

-

Peer Reviewer

-

Primary Author

-

Project Director

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Reviser

-

Revising Author

-

Second Author

-

Second Encoder

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Janelle Jenstad is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Janelle Jenstad is mentioned in the following documents:

Janelle Jenstad authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Jenstad, Janelle.

Building a Gazetteer for Early Modern London, 1550-1650.

Placing Names. Ed. Merrick Lex Berman, Ruth Mostern, and Humphrey Southall. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 2016. 129-145. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

The Burse and the Merchant’s Purse: Coin, Credit, and the Nation in Heywood’s 2 If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody.

The Elizabethan Theatre XV. Ed. C.E. McGee and A.L. Magnusson. Toronto: P.D. Meany, 2002. 181–202. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Early Modern Literary Studies 8.2 (2002): 5.1–26..The City Cannot Hold You

: Social Conversion in the Goldsmith’s Shop. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

The Silver Society Journal 10 (1998): 40–43.The Gouldesmythes Storehowse

: Early Evidence for Specialisation. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Lying-in Like a Countess: The Lisle Letters, the Cecil Family, and A Chaste Maid in Cheapside.

Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 34 (2004): 373–403. doi:10.1215/10829636–34–2–373. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Public Glory, Private Gilt: The Goldsmiths’ Company and the Spectacle of Punishment.

Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society. Ed. Anne Goldgar and Robert Frost. Leiden: Brill, 2004. 191–217. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Smock Secrets: Birth and Women’s Mysteries on the Early Modern Stage.

Performing Maternity in Early Modern England. Ed. Katherine Moncrief and Kathryn McPherson. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007. 87–99. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Using Early Modern Maps in Literary Studies: Views and Caveats from London.

GeoHumanities: Art, History, Text at the Edge of Place. Ed. Michael Dear, James Ketchum, Sarah Luria, and Doug Richardson. London: Routledge, 2011. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Versioning John Stow’s A Survey of London, or, What’s New in 1618 and 1633?.

Janelle Jenstad Blog. https://janellejenstad.com/2013/03/20/versioning-john-stows-a-survey-of-london-or-whats-new-in-1618-and-1633/. -

Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. Ed. Janelle Jenstad. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ & nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. Ed. Janelle Jenstad and the MoEML Team. MoEML. Transcribed. Web.

-

-

James Mardock

Dr. James Mardock teaches Renaissance literature at the University of Nevada. He has published articles on John Taylor, thewater-poet,

on Ben Jonson’s use of transvestism, and on Shakespeare and Dickens. His recent book, Our Scene is London (Routledge 2008), examines Jonson’s representation of urban space as an element in his strategy of self-definition. His chapter in Representing the Plague in Early Modern England (ed. Totaro and Gilman, Routledge 2010) explores King James’s accession and Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure as parallel cultural performances shaped by London’s1603 plague. Mardock is at work on an edition of quarto and folio Henry V for Internet Shakespeare Editions, for which he serves as assistant general editor, and a study of Calvinism and metatheatre in early modern drama. He has also served as the dramaturge for the Lake Tahoe Shakespeare Festival.James Mardock is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

James Mardock is mentioned in the following documents:

James Mardock authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Mardock, James. Our Scene is London: Jonson’s City and the Space of the Author. New York: Routledge, 2008. Print.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry V. Ed. James D. Mardock. Internet Shakespeare Editions. 11 May 2012. Open.

-

Martin D. Holmes

MDH

Programmer at the University of Victoria Humanities Computing and Media Centre (HCMC). Martin ported the MOL project from its original PHP incarnation to a pure eXist database implementation in the fall of 2011. Since then, he has been lead programmer on the project and has also been responsible for maintaining the project schemas. He was a co-applicant on MoEML’s 2012 SSHRC Insight Grant.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Author of abstract

-

Conceptor

-

Encoder

-

Markup editor

-

Name Encoder

-

Post-conversion and Markup Editor

-

Post-conversion processing and markup correction

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

Contributions by this author

Martin D. Holmes is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Martin D. Holmes is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Dr. Alexander Burnett

Doctor Alexander Burnett

(d. 25 August 1665)Doctor who attended Samuel Pepys. Resident of Fenchurch Street.Dr. Alexander Burnett is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Battersby

Master of the Apothecaries’ Company.John Battersby is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thomas Dekker is mentioned in the following documents:

Thomas Dekker authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Bevington, David. Introduction.

The Shoemaker’s Holiday.

By Thomas Dekker. English Renaissance Drama: A Norton Anthology. Ed. David Bevington, Lars Engle, Katharine Eisaman Maus, and Eric Rasmussen. New York: Norton, 2002. 483–487. Print. -

Dekker, Thomas. Britannia’s Honor.

The Dramatic Works of Thomas Dekker.

Vol. 4. Ed. Fredson Bowers. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1961. Print. -

Dekker, Thomas. The Dead Tearme. Or Westminsters Complaint for long Vacations and short Termes. Written in Manner of a Dialogue betweene the two Cityes London and Westminster. 1608. The Non-Dramatic Works of Thomas Dekker. Ed. Rev. Alexander B. Grosart. 5 vols. 1885. Reprint. New York: Russell and Russell, 1963. 4.1–84.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The Gull’s Horn-Book: Or, Fashions to Please All Sorts of Gulls. Thomas Dekker: The Wonderful Year, The Gull’s Horn-Book, Penny-Wise, Pound-Foolish, English Villainies Discovered by Lantern and Candelight, and Selected Writings. Ed. E.D. Pendry. London: Edward Arnold, 1967. 64–109. The Stratford-upon-Avon Library 4.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The Gul’s Horne-booke. London: [Nicholas Okes] for R. S[ergier?], 1609. Rpt. EEBO. Web.

-

Dekker, Thomas. If it be not good, the Diuel is in it A nevv play, as it hath bin lately acted, vvith great applause, by the Queenes Maiesties Seruants: at the Red Bull. London: Printed by Thomas Creede for John Trundle, 1612. STC 6507. EEBO.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Lantern and Candlelight. 1608. Ed. Viviana Comensoli. Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2007. Publications of the Barnabe Riche Society.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Londons Tempe, or The Feild of Happines. London: Nicholas Okes, 1629. STC 6509. DEEP 736. Greg 421a. Copy: British Library; Shelfmark: C.34.g.11.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Londons Tempe, or The Feild of Happines. London: Nicholas Okes, 1629. STC 6509. DEEP 736. Greg 421a. Copy: Huntington Library; Shelfmark: Rare Books 59055.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Londons Tempe, or The Feild of Happines. London: Nicholas Okes, 1629. STC 6509. DEEP 736. Greg 421a. Copy: National Library of Scotland; Shelfmark: Bute.143.

-

Dekker, Thomas. London’s Tempe. The Dramatic Works of Thomas Dekker. Ed. Fredson Bowers. Vol. 4. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1961. Print.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The magnificent entertainment giuen to King James, Queene Anne his wife, and Henry Frederick the Prince, upon the day of his Majesties triumphant passage (from the Tower) through his honourable citie (and chamber) of London, being the 15. of March. 1603. As well by the English as by the strangers: with the speeches and songes, deliuered in the severall pageants. London: Printed by Thomas Creede for Thomas Man the younger, 1604. EEBO. Reprint. Subscr.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The Magnificent Entertainment: Giuen to King James, Queene Anne his wife, and Henry Frederick the Prince, ypon the day of his Majesties Triumphant Passage (from the Tower) through his Honourable Citie (and Chamber) of London being the 15. Of March. 1603. London: T. Man, 1604. Treasures in full: Renaissance Festival Books. British Library. Web. Open.

-

Dekker, Thomas? The Owles almanacke prognosticating many strange accidents which shall happen to this kingdome of Great Britaine this yeere, 1618 : calculated as well for the meridian mirth of London, as any other part of Great Britaine : found in an Iuy-bush written in old characters / and now published in English by the painefull labours of Mr. Iocundary Merry-braines. London, 1618. EEBO. Reprint. Subscr.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Penny-wise pound foolish or, a Bristow diamond, set in two rings, and both crack’d Profitable for married men, pleasant for young men, and a rare example for all good women. London, 1631. EEBO. Reprint. Subscr.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The Second Part of the Honest Whore, with the Humors of the Patient Man, the Impatient Wife: the Honest Whore, perswaded by strong Arguments to turne Curtizan againe: her braue refuting those Arguments. London: Printed by Elizabeth All-de for Nathaniel Butter, 1630. STC 6506. EEBO.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The seuen deadly sinnes of London drawne in seuen seuerall coaches, through the seuen seuerall gates of the citie bringing the plague with them. London, 1606. EEBO. Reprint. Subscr.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The Shoemaker’s Holiday. Ed. R.L. Smallwood and Stanley Wells. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1979. The Revels Plays.

-

Dekker, Thomas. The Shomakers Holiday: or, The Gentle Craft With the Humorous Life of Simon Eyre, Shoomaker, and Lord Maior of London. London, 1600. EEBO. Reprint. Subscr.

-

Dekker, Thomas, Stephen Harrison, Ben Jonson, and Thomas Middleton. The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment of King James through the City of London, 15 March 1604, with the Arches of Triumph. Ed. R. Malcolm Smuts. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 219–79.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Troia-Noua Triumphans. London: Nicholas Okes, 1612. STC 6530. DEEP 578. Greg 302a. Copy: Chapin Library; Shelfmark: 01WIL_ALMA.

-

Dekker, Thomas. Westward Ho! The Dramatic Works of Thomas Dekker. Vol. 2. Ed. Fredson Bowers. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1964.

-

Middleton, Thomas, and Thomas Dekker. The Roaring Girl. Ed. Paul A. Mulholland. Revels Plays. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1987. Print.

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. Ed. Vittorio Gabrieli and Giorgio Melchiori. Revels Plays. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1990. Print.

-

Smith, Peter J.

Glossary.

The Shoemakers’ Holiday. By Thomas Dekker. London: Nick Hern, 2004. 108–110. Print.

-

Gilbert Dugdale

(fl. 1604)Gilbert Dugdale is mentioned in the following documents:

Gilbert Dugdale authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Dugdale, Gilbert. The time triumphant declaring in briefe, the arival of our soveraigne liedge Lord, King James into England, his coronation at Westminster: together with his late royal progresse, from the Towre of London throúgh the Cittie, to his Highnes manor of White Hall. Shewing also, the varieties & rarieties of al the sundry trophies or pageants, erected . . . With a rehearsall of the King and Queenes late comming to the Exchaunge in London. London, 1604. EEBO. Reprint. Subscr.

-

John Dymmocke

Property owner on Fenchurch Street.John Dymmocke is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 1I Queen of England Queen of Ireland Gloriana Good Queen Bess

(b. 7 September 1533, d. 24 March 1603)Queen of England and Ireland 1558-1603.Elizabeth I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Stephen Harrison is mentioned in the following documents:

Stephen Harrison authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Dekker, Thomas, Stephen Harrison, Ben Jonson, and Thomas Middleton. The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment of King James through the City of London, 15 March 1604, with the Arches of Triumph. Ed. R. Malcolm Smuts. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 219–79.

-

Harrison, Stephen. The arch’s of triumph erected in honor of the high and mighty prince. James. the first of that name. King, of England. and the sixt of Scotland at his Majesties entrance and passage through his honorable citty & chamber of London. upon the 15th. day of march 1603. Invented and published by Stephen Harrison ioyner and architect: and graven by William Kip. London, 1613. EEBO. Reprint. Subscr.

-

William Haughton is mentioned in the following documents:

William Haughton authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Haughton, William. English-men for my Money: or, A pleasant Comedy, called, A Woman will haue her Will. London, 1616. EEBO. Reprint. Subscr. STC 12931.

-

Thomas Heywood is mentioned in the following documents:

Thomas Heywood authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Heywood, Thomas. The Captives; or, The Lost Recovered. Ed. Alexander Corbin Judson. New Haven: Yale UP, 1921. Print.

-

Heywood, Thomas. The First and Second Parts of King Edward IV. Ed. Richard Rowland. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2005. The Revels Plays.

-

Heywood, Thomas. The Second Part of, If you know not me, you know no bodie. VVith the building of the Royall Exchange: And the Famous Victorie of Queene Elizabeth, in the Yeare 1588. London, 1606. STC 13336. EEBO. Web. Subscr.

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. Ed. Vittorio Gabrieli and Giorgio Melchiori. Revels Plays. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1990. Print.

-

Thomas Heywood Heywood’s Dramatic Works. 6 vols. Ed. W.J. Alexander. London: John Pearson, 1874. Print.

-

Ivan IV

Ivan This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 4IV the Terrible

(b. 1530, d. 1584)Czar of Russia and Grand Prince of Muscovy.Ivan IV is mentioned in the following documents:

-

James VI and I

James This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 6VI This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 1I King of Scotland King of England King of Ireland

(b. 1566, d. 1625)James VI and I is mentioned in the following documents:

James VI and I authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

James VI and I. Letters of King James VI and I. Ed. G.P.V. Akrigg. Berkeley: U of California P, 1984. Print.

-

Rhodes, Neill, Jennifer Richards, and Joseph Marshall, eds. King James VI and I: Selected Writings. By James VI and I. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004.

-

Ben Jonson is mentioned in the following documents:

Ben Jonson authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Chapman, George, Ben Jonson, and John Marston. Eastward Ho! Ed. R.W. Van Fossen. New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Print.

-

Dekker, Thomas, Stephen Harrison, Ben Jonson, and Thomas Middleton. The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment of King James through the City of London, 15 March 1604, with the Arches of Triumph. Ed. R. Malcolm Smuts. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 219–79.

-

Gifford, William, ed. The Works of Ben Jonson. By Ben Jonson. Vol. 1. London: Nichol, 1816. Remediated by Internet Archive.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Alchemist. London: New Mermaids, 1991. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Bartholomew Fair. Ed. E.A. Horsman. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1979. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Bartholomew Fair. Ed. Suzanne Gossett, based on The Revels Plays edition ed. E.A. Horsman. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2000. Revels Student Editions. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. B. Ion: his part of King Iames his royall and magnificent entertainement through his honorable cittie of London, Thurseday the 15. of March. 1603 so much as was presented in the first and last of their triumphall arch’s. London, 1604. STC 14756. EEBO.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Complete Poetry of Ben Jonson. Ed. William B. Hunter. Stuart Edtions. New York: New YorkUP, 1963.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Devil is an Ass. Ed. Peter Happé. Manchester and New York: Manchester UP, 1996. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Epicene. Ed. Richard Dutton. Revels Plays. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2004. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Every Man Out of His Humour. Ed. Helen Ostovich. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2001. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. The First, of Blacknesse, Personated at the Court, at White-hall, on the Twelfth Night, 1605. The Characters of Two Royall Masques: The One of Blacknesse, the Other of Beautie. Personated by the Most Magnificent of Queenes Anne Queene of Great Britaine, &c. with her Honorable Ladyes, 1605 and 1608 at White-hall. London : For Thomas Thorp, and are to be Sold at the Signe of the Tigers Head in Paules Church-yard, 1608. Sig. A3r-C2r. STC 14761. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Jonson, Ben. Oberon, The Faery Prince. The Workes of Benjamin Jonson. Vol. 1. London: Will Stansby, 1616. Sig. 4N2r-2N6r. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Staple of Newes. The Works. Vol. 2. London: Printed by I.B. for Robert Allot, 1631. Sig. 2A1r-2J2v. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Staple of News. Ed. Anthony Parr. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben.

To Penshurst.

The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt, Carol T. Christ, Alfred David, Barbara K. Lewalski, Lawrence Lipking, George M. Logan, Deidre Shauna Lynch, Katharine Eisaman Maus, James Noggle, Jahan Ramazani, Catherine Robson, James Simpson, Jon Stallworthy, Jack Stillinger, and M. H. Abrams. 9th ed. Vol. B. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2012. 1547. -

Jonson, Ben. The vvorkes of Beniamin Ionson. Containing these playes, viz. 1 Bartholomew Fayre. 2 The staple of newes. 3 The Divell is an asse. London, 1641. EEBO. Reprint. Subscr. STC 14754.

-

John Lute is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Henry Machyn is mentioned in the following documents:

Henry Machyn authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Machyn, Henry. The Diary of Henry Machyn, Citizen and Merchant-Taylor of London, From A.D. 1550 to A.D. 1563. Ed. John Gough Nichols. London, 1848. Print.

-

Machyn, Henry. A London Provisioner’s Chronicle, 1550–1563, by Henry Machyn: Manuscript, Transcription, and Modernization. Ed. Richard W. Bailey, Marilyn Miller, and Colette Moore. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2006. Open. [The Map of Early Modern London cites from this edition rather than Nichols’s nineteenth-century edition. We cite by the date of the entry thus: (Machyn 1550–08–04).]

-

Martial is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary Queen of Scotland

(b. 1542, d. 1587)Queen of Scotland 1542-1567. Queen of France 1559-1560.Mary, Queen of Scots is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Richard Mulcaster is mentioned in the following documents:

Richard Mulcaster authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Mulcaster, Richard. The Queen’s Majesty’s Passage. London: Printed by R. Tottill, 1559. SCN 7589.5. Ed. Jennie Butler and Janelle Jenstad. MoEML. Transcribed. Open.

-

Osip Nepeya is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Sir Thomas Offley is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Samuel Pepys is mentioned in the following documents:

Samuel Pepys authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Pepys, Samuel. The Diary of Samuel Pepys: A New and Complete Transcription. Ed. Robert Latham and William Matthews. 11 vols. Berkeley : U of California P, 1970–1983.

-

Pepys, Samuel. The Diary of Samuel Pepys: Daily Entries from the 17th Century London Diary. Dev. Phil Gyford. http://www.pepysdiary.com/.

-

Daniel Rawlinson is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Revell is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Stow

(b. between 1524 and 1525, d. 1605)Historian and author of A Survey of London. Husband of Elizabeth Stow.John Stow is mentioned in the following documents:

John Stow authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Blome, Richard.

Aldersgate Ward and St. Martins le Grand Liberty Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. M3r and sig. M4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Aldgate Ward with its Division into Parishes. Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections & Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H3r and sig. H4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Billingsgate Ward and Bridge Ward Within with it’s Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. Y2r and sig. Y3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Bishopsgate-street Ward. Taken from the Last Survey and Corrected.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. N1r and sig. N2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Bread Street Ward and Cardwainter Ward with its Division into Parishes Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. B3r and sig. B4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Broad Street Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections and Additions, & Cornhill Ward with its Divisions into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, &c.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. P2r and sig. P3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Cheape Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig.D1r and sig. D2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Coleman Street Ward and Bashishaw Ward Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. G2r and sig. G3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Cow Cross being St Sepulchers Parish Without and the Charterhouse.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H2v and sig. H3r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Creplegate Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, with Additions, and Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. I3r and sig. I4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Farrington Ward Without, with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections & Amendments.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. 2F3r and sig. 2F4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Lambeth and Christ Church Parish Southwark. Taken from ye last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. Z1r and sig. Z2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Langborne Ward with its Division into Parishes. Corrected from the Last Survey. & Candlewick Ward with its Division into Parishes. Corrected from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. U3r and sig. U4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Map of St. Gilles’s Cripple Gate. Without. With Large Additions and Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H2v and sig. H3r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Map of the Parish of St. Dunstans Stepney, als. Stebunheath Divided into Hamlets.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. F3r and sig. F4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Map of the Parish of St Mary White Chappel and a Map of the Parish of St Katherines by the Tower.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. F2r and sig. F3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of Lime Street Ward. Taken from ye Last Surveys & Corrected.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. M1r and sig. M2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of St. Andrews Holborn Parish as well Within the Liberty as Without.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. 2I1r and sig. 2I2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parishes of St. Clements Danes, St. Mary Savoy; with the Rolls Liberty and Lincolns Inn, Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig.O4v and sig. O1r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St. Anns. Taken from the last Survey, with Correction, and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. L2v and sig. L3r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St. Giles’s in the Fields Taken from the Last Servey, with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. K1v and sig. K2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Margarets Westminster Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig.H3v and sig. H4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Martins in the Fields Taken from ye Last Survey with Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. I1v and sig. I2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Pauls Covent Garden Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. L3v and sig. L4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Saviours Southwark and St Georges taken from ye last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. D1r and sig.D2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

The Parish of St. James Clerkenwell taken from ye last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H3v and sig. H4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

The Parish of St. James’s, Westminster Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. K4v and sig. L1r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

The Parish of St Johns Wapping. The Parish of St Paul Shadwell.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. E2r and sig. E3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Portsoken Ward being Part of the Parish of St. Buttolphs Aldgate, taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. B1v and sig. B2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Queen Hith Ward and Vintry Ward with their Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. 2C4r and sig. 2D1v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Shoreditch Norton Folgate, and Crepplegate Without Taken from ye Last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. G1r and sig. G2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Spitt Fields and Plans Adjacent Taken from Last Survey with Locations.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. F4r and sig. G1v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

St. Olave and St. Mary Magdalens Bermondsey Southwark Taken from ye last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. C2r and sig.C3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Tower Street Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. E2r and sig. E3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Walbrook Ward and Dowgate Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Surveys.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. 2B3r and sig. 2B4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

The Wards of Farington Within and Baynards Castle with its Divisions into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. Q2r and sig. Q3v. [See more information about this map.] -

The City of London as in Q. Elizabeth’s Time.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Frontispiece. -

A Map of the Tower Liberty.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H4v and sig. I1r. [See more information about this map.] -

A New Plan of the City of London, Westminster and Southwark.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Frontispiece. -

Pearl, Valerie.

Introduction.

A Survey of London. By John Stow. Ed. H.B. Wheatley. London: Everyman’s Library, 1987. v–xii. Print. -

Pullen, John.

A Map of the Parish of St Mary Rotherhith.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. Z3r and sig. Z4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Stow, John, Anthony Munday, and Henry Holland. THE SVRVAY of LONDON: Containing, The Originall, Antiquitie, Encrease, and more Moderne Estate of the sayd Famous Citie. As also, the Rule and Gouernment thereof (both Ecclesiasticall and Temporall) from time to time. With a briefe Relation of all the memorable Monuments, and other especiall Obseruations, both in and about the same CITIE. Written in the yeere 1598. by Iohn Stow, Citizen of London. Since then, continued, corrected and much enlarged, with many rare and worthy Notes, both of Venerable Antiquity, and later memorie; such, as were neuer published before this present yeere 1618. London: George Purslowe, 1618. STC 23344. Yale University Library copy Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Stow, John, Anthony Munday, and Humphrey Dyson. THE SURVEY OF LONDON: CONTAINING The Original, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of that City, Methodically set down. With a Memorial of those famouser Acts of Charity, which for publick and Pious Vses have been bestowed by many Worshipfull Citizens and Benefactors. As also all the Ancient and Modern Monuments erected in the Churches, not only of those two famous Cities, LONDON and WESTMINSTER, but (now newly added) Four miles compass. Begun first by the pains and industry of John Stow, in the year 1598. Afterwards inlarged by the care and diligence of A.M. in the year 1618. And now compleatly finished by the study &labour of A.M., H.D. and others, this present year 1633. Whereunto, besides many Additions (as appears by the Contents) are annexed divers Alphabetical Tables, especially two, The first, an index of Things. The second, a Concordance of Names. London: Printed for Nicholas Bourne, 1633. STC 23345.5. Harvard University Library copy Reprint. Early English Books Online. Web.

-

Stow, John. The chronicles of England from Brute vnto this present yeare of Christ. 1580. Collected by Iohn Stow citizen of London. London, 1580. Rpt. EEBO. Web.

-

Stow, John. A Summarie of the Chronicles of England. Diligently Collected, Abridged, & Continued vnto this Present Yeere of Christ, 1598. London: Imprinted by Richard Bradocke, 1598. Rpt. EEBO. Web.

-

Stow, John. A suruay of London· Conteyning the originall, antiquity, increase, moderne estate, and description of that city, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow citizen of London. Since by the same author increased, with diuers rare notes of antiquity, and published in the yeare, 1603. Also an apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that citie, the greatnesse thereof. VVith an appendix, contayning in Latine Libellum de situ & nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. London: John Windet, 1603. STC 23343. U of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign Campus) copy Reprint. Early English Books Online. Web.

-

Stow, John, The survey of London contayning the originall, increase, moderne estate, and government of that city, methodically set downe. With a memoriall of those famouser acts of charity, which for publicke and pious vses have beene bestowed by many worshipfull citizens and benefactors. As also all the ancient and moderne monuments erected in the churches, not onely of those two famous cities, London and Westminster, but (now newly added) foure miles compasse. Begunne first by the paines and industry of Iohn Stovv, in the yeere 1598. Afterwards inlarged by the care and diligence of A.M. in the yeere 1618. And now completely finished by the study and labour of A.M. H.D. and others, this present yeere 1633. Whereunto, besides many additions (as appeares by the contents) are annexed divers alphabeticall tables; especially two: the first, an index of things. The second, a concordance of names. London: Printed by Elizabeth Purslovv for Nicholas Bourne, 1633. STC 23345. U of Victoria copy.

-