MoEML Quickstart

This document is currently in draft. When it has been reviewed and proofed, it will

be

published on the site.

Please note that it is not of publishable quality yet.

MoEML Quickstart

¶Part I: Introduction to Markup

Unlike past generations of editors, we are producing texts that must be readable

by machines before they are rendered and made readable by humans. Therefore,

virtually every editorial choice must be tagged in such a way that a computer

can both interpret it and display it (

renderit) in an interface. We call this level of machine-readable information

markup.

Markup has the additional advantage that we can process a marked-up text in many

different ways. We can change how we render it. We can give readers options

(e.g., to turn things on or off, to change the font, to display the long S or

convert them all to short s). We can transform the marked-up text into many

different types of outputs: HTML pages for display on a website, PDFs, ePubs,

etc. We can index it, link to it, generate concordances from it, count things in

it (words, lines, etc.), search it, and store it for long-term digital

archiving.

The effort you put into markup makes your text extraordinarily valuable for many

users because it can be used for many diverse purposes.

¶What is Markup?

Markup is information added to a text in order to say something

about the text. As a skilled reader of texts, you already

have an incipient understanding of textual markup. White space, paragraph

breaks, italicization, punctuation, capitalization, square brackets, and

other features of a printed text are all forms of markup that signal

something to the reader. For example, we sometimes recognize poetry in early

modern texts because it is (often) italicized. The early modern printer set

poetry in italics to say something about the text. Are the italics

part of the text or are they saying something about

the text? That’s where print markup gets murky—computers need

much greater clarity than we need as human readers.

¶Terminology

Tagging, marking up, and encoding are

interchangeable gerunds.

The information added to a text is markup.

When we add markup to a text, we mark up the

text.

You will also see markup spelled mark-up or

mark up.

¶MoEML’s Markup Language

MoEML uses a markup language known as TEI-XML. It is a dialect of XML devised

by the Text Encoding Initiative (thus the acronym TEI), a consortium of

people who came together to devise a markup language specifically for

text-bearing objects (manuscripts, books, documents). XML stands for

eXtensible Markup Language. It is not a single language, but a set of

standards for writing XML languages. The standard was published in 1996 by

the World Wide Web Consortium. It was designed to replace SGML.

¶Elements, Attributes, and Values

What does markup look like? Let’s start with an example using italics.

Italics can indicate many different things:

-

Do you really want to know the truth?

-

Do you know what the word palimpsest means?

-

Stow is the author of the 1598 Survey of London.

-

This streete is also a part of Limestreete warde.

-

In the anno mundi calendar, the year 1 is the year the world was created.

A human reader can read ambiguous markup. When a human sees italics, they can

infer their meaning through contextual clues. A computer, however, can not.

As encoders, we must specify what italics mean in each given scenario:

-

Emphasis: Do you

<emph>really</emph>want to know the truth? -

Words as words: Do you know what the word

<term>palimpsest</term>means? -

Titles: Stow is the author of the 1598

<title>Survey of London</title>. -

Names: This streete is also a part of

<placeName>Limestreete warde</placename>. -

Foreign words: In the

<foreign>anno mundi</foreign>, the year 1 is the year the world was created.

descriptive markup.

An element is the tag that wraps an item in the text:

<title>Survey of London</title>

You can think of an element like a noun because it

describes what something is. Here, Survey of Londonis the text node. The text node is the thing you add markup to. When marking up a text node, it must be wrapped in both an opening tag (

<title>) and a closing tag (</title>).

But what if you want to specify what kind of title you have? You

can add an attribute and value to your element

tag:

<title level="m">Survey of London</title>

In this example, the attribute is @level and

the value is "m". You can think about attributes as

big categories—they are not specific until you add a value. In this example,

@level asks what type of title is Survey of London?and

"m"

answers, it’s a monograph!

To refresh:

-

The element describes what the text node is (i.e.,

<title>). -

The attribute is a category on the element (i.e.,

@level). -

The value specifies the attribute (i.e.,

"m").

As you can see, in Oxygen, elements, attributes, and values are different

colours. Note that attributes and values are only added to the opening

tag—the closing tag does not repeat them. It is also important to note that

elements can have more than one attribute:

<title level="m" when="1603">Survey of London</title>

In some cases, an element can be self closing. A common example is

the element <lb> (line beginning), which is explained in depth below.

While particular elements, attributes, and values can vary depending on the

XML language, the structure of an XML element is always the same.

¶Part II: Tagging John Stow’s Survey of London

At MoEML, we use a specific set of elements, attributes, and values. In our

editions of Survey of London, we tag bibliographical

codes, dates, organizations, toponyms, and people. So far, we have progress

charts of our 1598 and 1633 editions to track who did what and what remains to

be finished:

¶Tagging Bibliographical Codes

As an encoder working on a primary source document, your main job is to

represent the original source document as faithfully as possible. In other

words, you are using markup to describe how the text appears

(alignment, italics, etc.). The overriding concern here, however, is to

tell the truth. We do not mark up texts with the goal of

rendering them in a particular way; we mark up texts truthfully

to capture information about the page and then we render them how we would

like based on the markup. A good way to think about

bibliographical code markup is this: the MoEML website may not exist fifty

years from now, but the underlying XML documents that

make upthe website will. Therefore, when marking up a document, an encoder’s focus should not be on how the document appears on the current MoEML website, but to make sure that all bibliographical codes (paragraphs, italicization, punctuation, capitalization, etc.) are captured in a way that is helpful for future researchers and students.

¶Proofing the Transcription

Our editions of Survey of London began as

EEBO-TCP diplomatic transcriptions, which means that most of the text

was transcribed by non-MoEML encoders. Because of this, MoEML research

assistants need to proof each chapter against the manuscript to fix

errors and to make sure the text conforms with our project-wide

conventions.

Before you start proofing the transcription against the manuscript, read

Conventions for Diplomatic Transcriptions. It is

a short document that outlines which typographical, orthographical, and

compositorial features we retain in our editions of primary source

texts.

The manuscript pages you will need are already linked to each page:

You can also use this link to flip through UVic’s copy of the 1633 Survey of London that was digitized by Special

Collections.

In addition to proofing the actual text, you will need to proof a few

common bibliographical codes: line beginnings, hyphens, line groups,

italics, and marginal notes. Each is explained with examples below.

¶Line Beginnings and Hyphens

Self-closing

<lb> elements are used to indicate line beginnings in

prose:

<p>One being their Chieftain was called Robin Hoode, <lb/>who

required the king and his company, to ſtay & ſee his men

ſhoot <lb/>whereunto the king granting, Robin Hoode whiſtled,

and al the <lb/>200. Archers ſhot of, looſing all at once, and

when he whiſtled a<lb type="hyphenInWord"/>gaine they likewiſe

ſhot againe, their arrowes whiſtled by craft <lb/>of the heade,

ſo that the noiſe was ſtrange and lowde, which great<lb type="hyphenInWord"/>ly delighted the king and Queene and

their Companie.</p>

If you are adding a <lb> to your work, you only need to

use the one self-closing element because you are not qualifying a text

node (notice the / within the element). In the above example, note that

some of the line beginnings occur in the middle of words. For these

cases we use a self closing <lb> element with an attribute of

@type and a value of "hyphenInWord". As you can

see, the hyphen character (-) is not transcribed. Only transcribe the

hyphen character when it is actually part of a word:

<p>(or ſlip) of Gilli-flowers</p>

¶Line Groups

Most of Survey of London is written in prose and

is encoded with

<p> (paragraph) and <lb> (line beginning).

When Stow swtiches to poetry, however, we

use <lg> (line group) instead of <p> (paragraph) and wrap

each line in <l> (line):

<lg>

<l>Mighty Flora, Goddeſſe of freſh flowers,</l>

<l>which clothed hath the ſoile in luſtie greene.</l>

<l>Made buds ſpring, with her ſweete ſhowers,</l>

<l>by influence of the Sun ſhine.</l>

<l>To doe pleaſance of intent full cleane,</l>

<l>vnto the States which now ſit here.</l>

<l>Hath Vere downe ſent her owne daughter deare.</l>

</lg>

<l>Mighty Flora, Goddeſſe of freſh flowers,</l>

<l>which clothed hath the ſoile in luſtie greene.</l>

<l>Made buds ſpring, with her ſweete ſhowers,</l>

<l>by influence of the Sun ſhine.</l>

<l>To doe pleaſance of intent full cleane,</l>

<l>vnto the States which now ſit here.</l>

<l>Hath Vere downe ſent her owne daughter deare.</l>

</lg>

¶Renditions

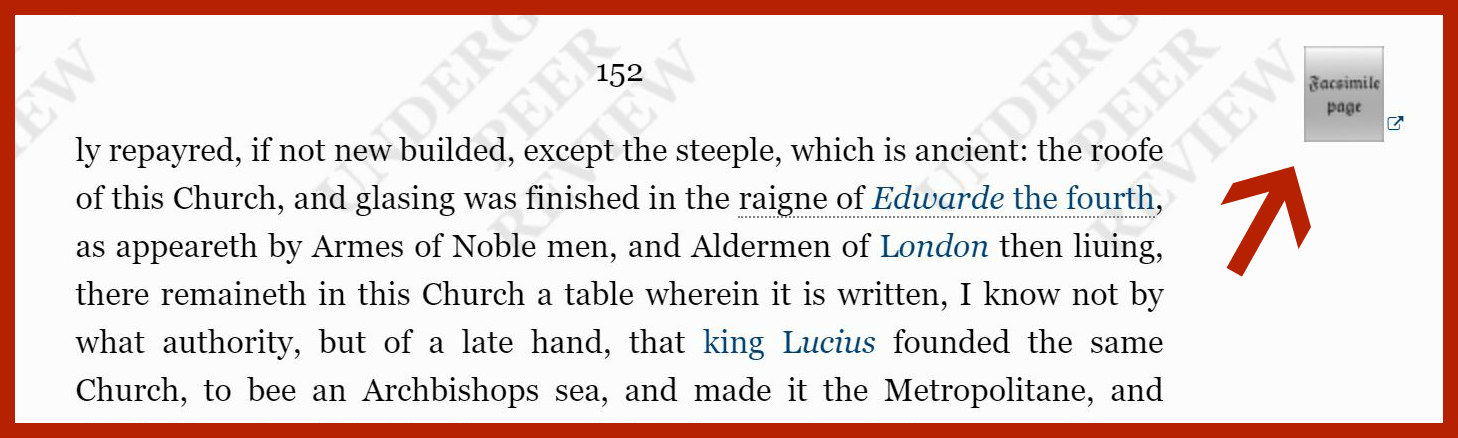

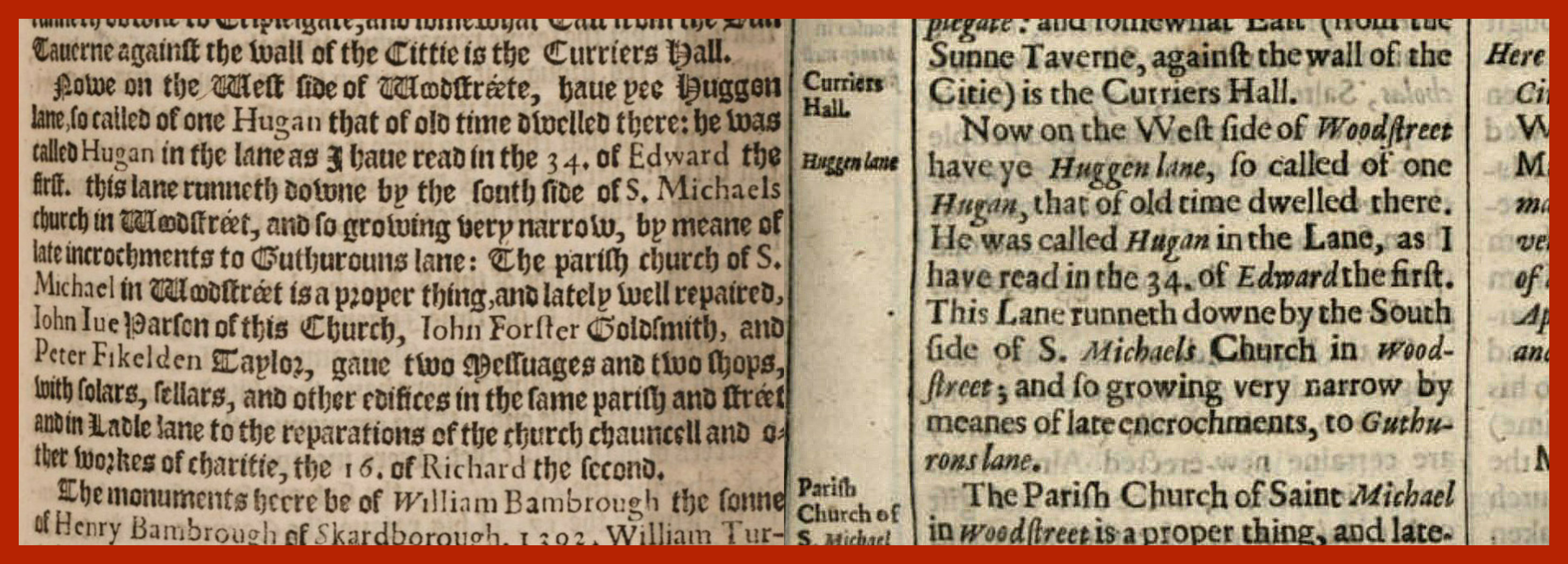

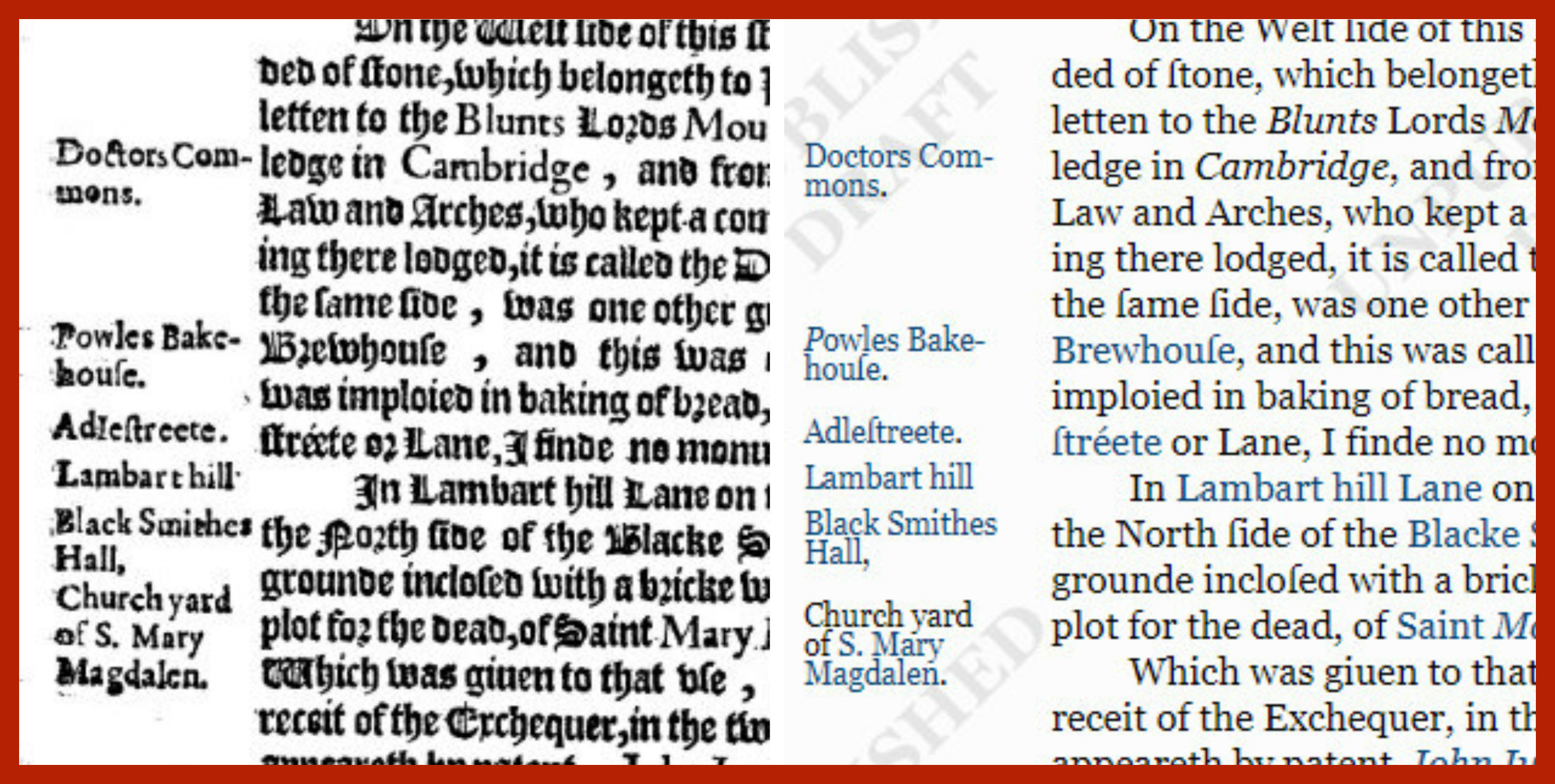

Below are images of the 1598 Survey of London

(left) and the 1633 Survey of London

(right):

Note that in 1598, the text sometimes changes font, and in 1663, the text

is sometimes italicized. These features are called

renditions.

Since certain feautures of the text (i.e., font, italics) tend to appear

the same way throughout our editions, it would be impractical to

individually

styleevery case (for example, imagine having to add the font type, font weight, and font size every time you wanted to italicize something). Instead, we add descriptions called

renditionsto the teiHeader of our primary source documents and refer back to them in our encoding. All renditions are nested under

<tagsDecl>. If you are interested in

learning more about the teiHeader and styling, see Encoding

Primary Sources.

These are the elements, attributes, and values you will use to tag 1598:

-

Element:

<hi> -

Attributes:

@rendition -

Values:

"#stow_1598_xml:id_R"

-

Element:

<hi> -

Attributes:

@rendition -

Values:

"#stow_1633_xml:id_IR"

"#" + xml:id of the chapter (i.e.,

"stow_1598_xml:id") + "_R". To encode the italics

in 1633, use the value "#" + xml:id of the chapter (i.e.,

"stow_1633_xml:id") + "_IR". There are more

renditions than these (find them under <tagsDecl> in your document), but these are the main ones you will need to

know.

Here is how the text node looks when it is marked up. The rendition element

in the header is also shown:

<!-- In the header: -->

<rendition scheme="css" xml:id="stow_1598_FARR1_R">font-family: "Georgia";</rendition>

<!-- In the body text: -->

<p><name rendition="#stow_1598_FARR1_R" ref="mol:FISH10">Iohn Fiſher</name> Mercer gaue <hi rendition="#stow_1598_FARR1_R">600</hi>.</p>

Note that if the text node is already wrapped

in a <name> or <ref> element (both of which are explained

in depth below), you can add the attribute (@rendition) and

value ("#stow_1598_xml:id_R" or

"#stow_1633_xml:id_IR") directly to the present element. If

not, wrap the text node with the <hi> element and then add the correct

attributes and values.

¶Marginal Notes

Like italics, marginal notes tend to appear the same way throughout

Survey of London. Because of this, the same

system with the teiheader and styling is used. For now, all you need to

know is what elements, attributes, and values are needed to wrap the

text node of a marginal note.

These are the elements, attributes, and values you will use to tag

marginal notes in 1598:

-

Element:

<label> -

Attributes:

@place -

Values:

"margin-left","margin-right"

-

Element:

<label> -

Attributes:

@place,@rendition -

Values:

"margin-left","margin-right","#stow_1633_xm:id_lmlabel"

<p>THe ſecond warde within the wall on the eaſt part is called Ealdgate warde, <label place="margin-left">Ealdgate ward</label> as taking name of the ſaide gate, the principall ſtreete of this warde begineth at

Ealdgate.</p>

Marginal note in 1633:

<p>Now in Friday ſtreet, <label rendition="#stow_1633_BREA3_lmlabel" place="margin-left">Friday ſtreet.</label> ſo called of Fiſhmongers dwelling there.</p>

As you can see in the above examples, marginal notes are

located directly within the text. When it comes to rendering, they

render either to the left or right ("margin-left" or

"margin-right") in line with the surrounding text.

This is is a side-by-side comparison of the 1598 Survey

of London manuscript on EEBO and the edition we have created

on the MoEML website. As you can see, our text looks similar to the

manuscript:

¶Tagging Dates, Companies, Toponyms, and People

In addition to tagging bibliographical codes, we also tag dates,

organizations, toponyms, and people. By doing this, we are able to link our

texts to MoEML’s rich encyclopedia which includes an orgography,

placeography, and personography.

Here is a quick summary of what the tags will look like. They will be

explained in more detail below:

| Situation | Example |

| Julian Date |

<date when-custom="1598" datingMethod="mol:julianSic" calendar="mol:julianSic">1598</date>

|

| Reign of Monarch |

<date when-custom="r_HENR6" datingMethod="mol:regnal" calendar="mol:regnal">reigne of <name ref="mol:HENR6">king

Henry the ſecond</name></date>

|

| Specific Year within Reign of Monarch |

<date when-custom="r_HENR6_09" datingMethod="mol:regnal" calendar="mol:regnal">ninth of <name ref="mol:HENR6">king

Henry the ſecond</name></date>

|

| Organizations |

<name ref="mol:META1" type="org">Merchant Taylors’

Company</name>

|

| Places |

<ref target="mol:TOWE5">Tower of London</ref>

|

| People |

<name ref="mol:STOW6">John Stow</name>

|

Before we discuss how to tag Survey of London, try

to identify the elements, attributes,

values, and text nodes in the above

examples—remember they are colour coded!

¶Tagging Dates

In Survey of London, you will need to know how

to tag three types of dates: regular dates in the Julian calendar,

reigns of monarchs, and specific years within reigns of monarchs.

These are the elements, attributes, and values you will use to tag dates:

-

Element:

<date> -

Attributes:

@when-custom,@datingMethod,@calendar -

Values:

"mol:julianSic","mol:regnal","mol:r_xml:id","mol:r_xml:id_#"

The Julian calendar was used in England until 1752. In Survey of London, therefore, we must tell the computer that

the dates being tagged are from the Julian calendar:

He died on the

<date when-custom="1417-09-28" calendar="mol:julianSic" datingMethod="mol:julianSic">28 of September in 1417</date>

-

Note that the attribute

@when-customis used for the Julian calendar (the attribute@whenis used for the Gregorian calendar, which you will not need to tag Survey of London). -

Note that the value of

@when-customis the date mentioned in the text in year-month-day format (YYYY-MM-DD). -

Note that the value of

@calendarand@datingMethodis"mol:julianSic". There is also"mol:julianMar"(when the source considers March 25 the start of the new year) and"mol:julianJan"(when the source considers January 1 the start of the new year). We use"mol:julianSic"in Survey of London because it is unclear which calendar Stow used.

In 2019, the MoEML team created a new way to tag the reigns of monarchs

and specific years within reigns. This means that in the 1598 Survey of London, regnal dates have been tagged

slightly differently. Use the method below to tag 1633:

In the <date when-custom="r_MARY2" datingMethod="mol:regnal" calendar="mol:regnal">reigne of <name ref="mol:MARY2">Queene

Mary</name></date>

-

Note that the word

the

is not included in the text node. -

Note that the value of

@when-customis"r_xml:id". Insert the xml:id of the monarch in question (in this case,"MARY2"). -

Note that the value of

@calendarand@dathingMethodis"mol:regnal".

To tag a specific year of a reign, add the year after the xml:id:

In the <date when-custom="r_EDWA1_08" datingMethod="mol:regnal" calendar="mol:regnal">eighth of <name ref="mol:EDWA1">Edward the

first</name></date>

-

The value of

@when-customis"r_xml:id_#". Insert the xml:id of the monarch in question and the year of their reign (in this case,"r_EDWA1_08").

For a thorough explanation of how to encode all different types of dates,

see Encode a

Date in Praxis.

¶Tagging Organizations

Tagging organizations is relatively straightforward. The most complicated

part is determining what should/should not be tagged and what

should/should not be part of the text node.

These are the elements, attributes, and values you will use to tag

organizations:

-

Element:

<name> -

Attributes:

@ref,@type -

Values:

"mol:xml:id","org"

Roles/occupations are not tagged:

<name ref="mol:LEOF1">Leafſtanus</name> the Goldſmith

Companies as a whole are tagged:

He was free of

the <name ref="mol:VINT3" type="org">Vintners</name>.

Of Londonis not part of the tag and should be tagged as a location:

The <name ref="mol:META1" type="org">Marchant Taylors</name> of <ref target="mol:LOND5">London</ref>

Most of the organizations Stow mentions in

Survey of London are the Twelve Great

Livery Companies (Mercers, Grocers, Drapers, Fishmongers, Goldsmiths, Skinners, Merchant

Taylors, Haberdashers, Salters,

Ironmongers, Vintners, and Clothworkers). There are also

lesser livery companies. To see the full list, visit the Orgography. Note that organizations can

also be groups (e.g., Black

Friars) or other companies (e.g., East India Company).

¶Tagging Toponyms

Tagging toponyms is one of the most important parts of marking up Survey of London. While the tag itself is not

complicated, it can be difficult to determine certain toponyms because

(1) location names in the early modern period were not standardized, and

(2) some locations have multiple (very different!) names.

Let’s take Arundel House as an example.

Here are just a few of its variant names: Arondell-Howse, Bath House,

Bath Inn, Bath Place, Charterhouse, City-House, Hampton Place, House of

the Bishop of Bath and Wells, Howard House, Inn of the Bishop of Bath

and Wells, Seymour Place.

You are obviously not expected to just

knowthat Arundel House was also called

Bath Innor

Hampton Place—that’s what MoEML is for! Therefore, when you come across a location in the Survey of London, you have a two options:

-

Check previous MoEML editions of Survey of London to see how the location was tagged.

-

Search the Gazetteer for variant names.

These are the elements, attributes, and values you will use to tag

places:

-

Element:

<ref> -

Attributes:

@target -

Values:

"mol:xml:id"

The word

theis not included in the text node:

vp by the <ref target="mol:GUIL1">Guildhal</ref>

When

Parishis part of a name, it is included in the text node:

to the <ref target="mol:STAU3">Parish Church of S. Augustine</ref>

Parishescan be locations in themselves:

Messuage in

the <ref target="mol:STOL104">Parish of S. Olave</ref>

Also note that the xml:id of parishes is usually the xml:id of

the church, plus 100 added to the number. For example, the xml:id of

All Hallows the Less is

"ALLH7" and the xml:id of the parish of All Hallows the Less is "ALLH107". The

xml:id of St. John Zachary is

"STJO6" and the xml:id of the parish of St. John Zachary is "STJO106".

¶Tagging People

Like early modern placenames, the names of people in Survey of London can be tricky. While some people are

obvious (e.g.,

king Henry the thirdeis

Henry IIIin our Personography), others are less so (e.g., we currently have six different people named

William Brown(e)in our Personography). Since spelling was not standardized in the early modern period, you often have to rely on contextual clues to determine who Stow is referring to.

Note that, due to early modern spelling variations, it is sometimes

difficult to find the person you are looking for in the A-Z Index. For

example, this is how Henry le Waleys

appears in different sections of Survey of

London:

-

1598 Temporal Government:

Henry Waleys

-

1598 Cheap Ward:

Henry Wales

-

1633 Dowgate Ward:

Henry Wallis

-

1633 Farringdon Within Ward:

H. Wales

If you were to search for

Henry Waleysin the A-Z Index, you would not find his entry because he is listed as

Henry le Waleys.To get around this problem, we recommend that you include many variant spellings of a person’s name in your search. It can also be helpful to search small parts of names (e.g.,

Henryor

Wal) and manually click through the results.

These are the elements, attributes, and values you will use to tag names:

-

Element:

<name> -

Attributes:

@ref -

Values:

"mol:xml:id"

Titles (i.e., King, Queen, Sir, Dame, Lord, Lady, etc.) are

included in the text node:

<name ref="mol:HENR7">king Henry the thirde</name>

<name ref="mol:YARF1">Sir Iames Yarforde</name>

Indirect references/pronouns are not tagged (even if we know

who is being referred to):

He dwelled

right againſt the <ref target="mol:GOLD2">Goldſmithes

Hall</ref>.

¶Common Mistakes

Compare these passages from Survey of London to

the examples explained above. Can you tell what should be fixed?

Question 1:

<p><name ref="mol:WITT1">Robert Wittingham</name>

<name ref="mol:DRAP3" type="org">Draper</name> laide the thirde ſtone, <name ref="mol:BART5">Henry Barton</name> then Maior.</p>

Answer: In this passage, <name ref="mol:DRAP3" type="org">Draper</name> laide the thirde ſtone, <name ref="mol:BART5">Henry Barton</name> then Maior.</p>

Draperrefers to the occupation of Robert Wittingham and should not be tagged.

<p><name ref="mol:WITT1">Robert Wittingham</name> Draper laide the

thirde ſtone, <name ref="mol:BART5">Henry Barton</name> then

Maior.</p>

Question 2:

<p>Lower downe from this pariſh church bee diuers fayre houſes

namely one wherein of late Sir <name ref="mol:BAKE9">Richard

Baker</name> a knight of Kent was lodged, and one wherein

dwelled maiſter <name ref="mol:GORE2">Thomas Gore</name> a

marchant famous for Hoſpitality.</p>

Answer: Sirshould be included in the text node.

<p>Lower downe from this pariſh church bee diuers fayre houſes

namely one wherein of late <name ref="mol:BAKE9">Sir Richard

Baker</name> a knight of Kent was lodged, and one wherein

dwelled maiſter <name ref="mol:GORE2">Thomas Gore</name> a

marchant famous for Hoſpitality.</p>

Question 3:

<p>One the moſt ancient houſe in this lane is called the <ref target="mol:LEAD3">leaden porch</ref>, and belonged ſomtime

to <name ref="mol:MERS1">Sir Iohn Merſton</name> knight: <date when-custom="r_EDWA3_01" datingMethod="mol:regnal" calendar="mol:regnal">the 1. of <name ref="mol:EDWA6">Edward

the 4</name></date>.</p>

Answer: The word theshould not be included in the text node and the value

"r_EDWA3_01" is

incorrect in the <date> element (i.e., "EDWA3" should be

"EDWA6").

<p>One the moſt ancient houſe in this lane is called the <ref target="mol:LEAD3">leaden porch</ref>, and belonged ſomtime

to <name ref="mol:MERS1">Sir Iohn Merſton</name> knight: the

<date when-custom="r_EDWA6_01" datingMethod="mol:regnal" calendar="mol:regnal">1. of <name ref="mol:EDWA6">Edward the

4</name></date>.</p>

Question 4:

<p>Then is <name ref="mol:ABCH1">Abchurch lane</name>, which is

on both the ſides, almoſt wholly of this ward.</p>

Answer: Since Abchurch laneis a location, it should be tagged with

<ref> and @target, not

<name> and @ref.

<p>Then is

<ref target="mol:ABCH1">Abchurch lane</ref>, which is on

both the ſides, almoſt wholly of this ward.</p>

The more time you spend tagging Survey of

London, the better you will become at noticing mistakes. We

encourage you to refer back to the examples in this document as you

work. Before you know it, the rules listed above will become habit.

¶Part III: Adding Organizations, Toponyms, and People

Once you feel comfortable marking up Survey of London,

the next thing to learn is how to add new organizations, toponyms, and people to

the MoEML database.

¶Adding Organizations to ORGS1.xml

When you come across an organization that is not in the A-Z Index, you will

need to add it to ORGS1.xml, MoEML’s Orgography file. For a quick

explanation of how to add many different types of organizations to

ORGS1.xml, see Website

and Document Structure in Praxis.

Since the Twelve Great Livery Companies have already been added to ORGS1.xml,

you will only be adding lesser livery companies and other early modern

organizations and offices. One thing to note is that the sequence of entries

in ORGS1.xml is rendered as it is encoded, which means that (1) entries must

be added to the correct section of ORGS1.xml, and (2) entries must be added

in alphabetical order.

¶Lesser Livery Companies

Lesser livery companies have very standardized entries. They are added

alphabetically under the

Lesser Livery Companiesheader:

<org xml:id="BAKE4" type="lesser">

<orgName>Worshipful Company of Bakers<reg>Bakers’ Company</reg></orgName>

<note><p>The <name type="org" ref="mol:BAKE4">Bakers’ Company</name> was one of the lesser livery companies of <ref target="mol:LOND5">London</ref>. The <name type="org" ref="mol:BAKE4">Worshipful Company of Bakers</name> is still active and maintains a website at <ref target="http://www.bakers.co.uk//">http://www.bakers.co.uk//</ref> that includes a <ref target="http://www.bakers.co.uk/A-Brief-History.aspx">history of the company</ref>.</p></note>

</org>

In the example above, find:

<orgName>Worshipful Company of Bakers<reg>Bakers’ Company</reg></orgName>

<note><p>The <name type="org" ref="mol:BAKE4">Bakers’ Company</name> was one of the lesser livery companies of <ref target="mol:LOND5">London</ref>. The <name type="org" ref="mol:BAKE4">Worshipful Company of Bakers</name> is still active and maintains a website at <ref target="http://www.bakers.co.uk//">http://www.bakers.co.uk//</ref> that includes a <ref target="http://www.bakers.co.uk/A-Brief-History.aspx">history of the company</ref>.</p></note>

</org>

-

"BAKE4": this value is the Bakers’ Company’s xml:id. -

"lesser": this value is used for all lesser livery companies. -

<reg>Bakers’ Company</reg>: note thatBakers’ Company

is wrapped in a<reg>element. -

London: note thatLondon

is tagged as a location. -

http://www.bakers.co.uk//: note that the URL for the Bakers’ Company’s website is wrapped with a<ref>element. Add a@typeattribute and the URL of the website as the value ("http://www.bakers.co.uk//") to make a link to the website. -

history of the company: most lesser livery company websites include a page on the history of the company, which is linked here.

Other Early Modern Organizations and Officessection of ORGS1.xml.

¶Other Early Modern Organizations and Offices

If an organization is not a (1) great livery company, (2) playing

company, or (3) lesser livery comapny, it goes under the

Other Early Modern Organizations and Officesheader. While these entries are largely unstandardized, each begins with

The [Name of Company]and is written in complete sentences (unlike PERS1.xml entries which are written in fragments):

<org xml:id="AUGU4" type="other">

<orgName>Austin Friars (Augustinians)</orgName>

<note><p>The <name type="org" ref="mol:AUGU4">Austin Friars</name> were a mendicant order that adhered to the teachings of <name ref="mol:AUGU5">Augustine of Hippo</name>. Founded in the thirteenth century, the <name type="org" ref="mol:AUGU4">Austin Friars</name> arrived in <ref target="mol:ENGL2">England</ref> in <date datingMethod="mol:julianSic" calendar="mol:julianSic" when-custom="1248">1248</date> and occupied <ref target="mol:AUST1">Austin Friars</ref> until <name ref="mol:HENR1">King Henry VIII</name>’s Dissolution of the Monasteries in <date datingMethod="mol:julianSic" calendar="mol:julianSic" when-custom="1538">1538</date>.</p>

</note>

</org>

<orgName>Austin Friars (Augustinians)</orgName>

<note><p>The <name type="org" ref="mol:AUGU4">Austin Friars</name> were a mendicant order that adhered to the teachings of <name ref="mol:AUGU5">Augustine of Hippo</name>. Founded in the thirteenth century, the <name type="org" ref="mol:AUGU4">Austin Friars</name> arrived in <ref target="mol:ENGL2">England</ref> in <date datingMethod="mol:julianSic" calendar="mol:julianSic" when-custom="1248">1248</date> and occupied <ref target="mol:AUST1">Austin Friars</ref> until <name ref="mol:HENR1">King Henry VIII</name>’s Dissolution of the Monasteries in <date datingMethod="mol:julianSic" calendar="mol:julianSic" when-custom="1538">1538</date>.</p>

</note>

</org>

<org xml:id="HANS4" type="other">

<orgName>Hanseatic League</orgName>

<note><p>The <name type="org" ref="mol:HANS4">Hanseatic League</name> was a confederation of German merchant guilds and market towns with outposts throughout Northern Europe, including <ref target="mol:ENGL2">England</ref>.</p></note>

</org>

Companies that were the precursors of one of the

Twelve Great Livery Companies have slightly more standardized entries:

<orgName>Hanseatic League</orgName>

<note><p>The <name type="org" ref="mol:HANS4">Hanseatic League</name> was a confederation of German merchant guilds and market towns with outposts throughout Northern Europe, including <ref target="mol:ENGL2">England</ref>.</p></note>

</org>

<org xml:id="FRAT3" type="other">

<orgName>Fraternity of Taylors and Linen Armourers of St. John the Baptist</orgName>

<note><p>The <name type="org" ref="mol:FRAT3">Fraternity of Taylors and Linen Armourers of St. John the Baptist</name> was the precursor of the <name type="org" ref="mol:META1">Merchant Taylors’ Company</name>.</p></note>

</org>

If two companies merged to create one of the Great Twelve

Livery Companies, their entries are as follows:

<orgName>Fraternity of Taylors and Linen Armourers of St. John the Baptist</orgName>

<note><p>The <name type="org" ref="mol:FRAT3">Fraternity of Taylors and Linen Armourers of St. John the Baptist</name> was the precursor of the <name type="org" ref="mol:META1">Merchant Taylors’ Company</name>.</p></note>

</org>

<org type="other" xml:id="SHEA1">

<orgName>Shearmens’ Company</orgName>

<note><p>The <name type="org" ref="mol:FULL2">Shearmens’ Company</name> was the precursor of the <name type="org" ref="mol:CLOT2">Clothworkers’ Company</name>, into which it merged with the <name type="org" ref="mol:FULL2">Fullers’ Company</name> in <date calendar="mol:julianSic" datingMethod="mol:julianSic" when-custom="1528">1528</date>.</p>

</note>

</org>

<orgName>Shearmens’ Company</orgName>

<note><p>The <name type="org" ref="mol:FULL2">Shearmens’ Company</name> was the precursor of the <name type="org" ref="mol:CLOT2">Clothworkers’ Company</name>, into which it merged with the <name type="org" ref="mol:FULL2">Fullers’ Company</name> in <date calendar="mol:julianSic" datingMethod="mol:julianSic" when-custom="1528">1528</date>.</p>

</note>

</org>

<org type="other" xml:id="FULL2">

<orgName>Fullers’ Company</orgName>

<note><p>The <name type="org" ref="mol:FULL2">Fullers’ Company</name> was the precursor of the <name type="org" ref="mol:CLOT2">Clothworkers’ Company</name>, into which it merged with the <name type="org" ref="mol:SHEA1">Shearmens’ Company</name> in <date calendar="mol:julianSic" datingMethod="mol:julianSic" when-custom="1528">1528</date>.</p>

</note>

</org>

<orgName>Fullers’ Company</orgName>

<note><p>The <name type="org" ref="mol:FULL2">Fullers’ Company</name> was the precursor of the <name type="org" ref="mol:CLOT2">Clothworkers’ Company</name>, into which it merged with the <name type="org" ref="mol:SHEA1">Shearmens’ Company</name> in <date calendar="mol:julianSic" datingMethod="mol:julianSic" when-custom="1528">1528</date>.</p>

</note>

</org>

¶Adding Toponyms

¶Adding People to PERS1.xml

When you come across a person who is not in the A-Z Index, you will need to

add them to PERS1.xml, MoEML’s Personagraphy file. For a thorough

explanation of how to add many different types of people to PERS1.xml, see

Encode

Persons in Praxis.

Below, we have broken down entries that are particularly common in Survey of London. Unlike ORGS1.xml, PERS1.xml is

programmatically rendered in alphabetical order. Because of this, for ease,

add new entries to the end of the document.

¶Lord Mayors and Sheriffs

Lord mayors and sheriffs have very standardized entries. One of the most

helpful resources for information on these figures is Mayors and Sheriffs of London (MASL). The MASL database includes the names, years of office, and livery company

membership of London’s mayors, sheriffs, and wardens.

When writing an entry for a lord mayor, include their years as sheriff

(if applicable), years as mayor, livery company membership, and any

additional information that appears in Survey of

London such as their family members or place of

burial:

<person xml:id="CHIC4" sex="1">

<persName type="hist">

<reg>Sir Robert Chichele</reg>

<roleName>Sir</roleName>

<forename>Robert</forename>

<surname>Chichele</surname>

<roleName>Sheriff</roleName>

<roleName>Mayor</roleName>

</persName>

<death notBefore-custom="1439-06-05" notAfter-custom="1439-11-06" datingMethod="mol:julianSic"/>

<note><p>Sheriff of <ref target="mol:LOND5">London</ref>

<date datingMethod="mol:julianSic" from-custom="1402" to-custom="1403">1402-1403</date>. Mayor <date datingMethod="mol:julianSic" from-custom="1411" to-custom="1412">1411-1412</date> and <date datingMethod="mol:julianSic" from-custom="1421" to-custom="1422">1421-1422</date>. Member of the <name type="org" ref="mol:GROC3">Grocers’ Company</name>. Brother of <name ref="mol:CHIC5">Henry Chichele</name> and <name ref="mol:CHIC7">William Chichele</name>. Cousin of <name ref="mol:CHIC3">Dr. William Chichele</name>.</p>

<list type="links">

<item><ref target="http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1386-1421/member/chichele-robert-1439"><title level="m">HPO</title></ref></item>

<item><ref target="https://masl.library.utoronto.ca/person_detaild9f2.html?person_id=432"><title level="m">MASL</title></ref></item>

<item><ref target="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Chichele"><title level="m">Wikipedia</title></ref></item>

</list>

</note>

</person>

In the example above, find:

<persName type="hist">

<reg>Sir Robert Chichele</reg>

<roleName>Sir</roleName>

<forename>Robert</forename>

<surname>Chichele</surname>

<roleName>Sheriff</roleName>

<roleName>Mayor</roleName>

</persName>

<death notBefore-custom="1439-06-05" notAfter-custom="1439-11-06" datingMethod="mol:julianSic"/>

<note><p>Sheriff of <ref target="mol:LOND5">London</ref>

<date datingMethod="mol:julianSic" from-custom="1402" to-custom="1403">1402-1403</date>. Mayor <date datingMethod="mol:julianSic" from-custom="1411" to-custom="1412">1411-1412</date> and <date datingMethod="mol:julianSic" from-custom="1421" to-custom="1422">1421-1422</date>. Member of the <name type="org" ref="mol:GROC3">Grocers’ Company</name>. Brother of <name ref="mol:CHIC5">Henry Chichele</name> and <name ref="mol:CHIC7">William Chichele</name>. Cousin of <name ref="mol:CHIC3">Dr. William Chichele</name>.</p>

<list type="links">

<item><ref target="http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1386-1421/member/chichele-robert-1439"><title level="m">HPO</title></ref></item>

<item><ref target="https://masl.library.utoronto.ca/person_detaild9f2.html?person_id=432"><title level="m">MASL</title></ref></item>

<item><ref target="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Chichele"><title level="m">Wikipedia</title></ref></item>

</list>

</note>

</person>

-

"CHIC4": this value is Sir Robert Chichele’s xml:id. -

@sex: the value"1"is used for males and the value"2"is used for females. -

"hist": almost all people in Survey of London are historical ("hist"). If you are adding a literary or allegorical character, this value would be changed to"lit". -

<reg>Sir Robert Chichele</reg>: the person’s full name, including titles (Sir, Dame, etc.), goes here. Since spelling was not standardized in the early modern period, choosing the spelling of the name can be difficult. For mayors and sheriffs, we use the spelling found on MASL. For people with no ONDB or Wikipedia page, we use the spelling used by Stow. See Encode Persons for a full explanation of<reg>. -

<roleName>Sir</roleName>: some people have multple role names. If the role name is a title (i.e., Sir), it goes before the<forename>and<surname>. If it is a position (i.e., Sheriff, Mayor, etc.) it goes after. See Encode Persons for a full explanation of<roleName>. -

Henry ChicheleandWilliam Chichele: whenever a person is mentioned in another person’s PERS1.xml entry, their<reg>name should be used.

Entries for sheriffs look very similar to that of lord mayors:

<person xml:id="FORD7" sex="1">

<persName type="hist">

<reg>Thomas de Ford</reg>

<forename>Thomas</forename>

<surname><nameLink>de</nameLink> Ford</surname>

<roleName>Sheriff</roleName>

</persName>

<note><p>Sheriff of <ref target="mol:LOND5">London</ref>

<date datingMethod="mol:julianSic" from-custom="1263" to-custom="1264">1263-1264</date>.</p>

<list type="links">

<item><ref target="https://masl.library.utoronto.ca/person_detail11f8.html?person_id=531"><title level="m">MASL</title></ref></item>

</list>

</note>

</person>

In the example above, find:

<persName type="hist">

<reg>Thomas de Ford</reg>

<forename>Thomas</forename>

<surname><nameLink>de</nameLink> Ford</surname>

<roleName>Sheriff</roleName>

</persName>

<note><p>Sheriff of <ref target="mol:LOND5">London</ref>

<date datingMethod="mol:julianSic" from-custom="1263" to-custom="1264">1263-1264</date>.</p>

<list type="links">

<item><ref target="https://masl.library.utoronto.ca/person_detail11f8.html?person_id=531"><title level="m">MASL</title></ref></item>

</list>

</note>

</person>

-

<nameLink>: for surnames with alinking

parts (i.e.,de

orvan

) we tag them with<nameLink>. See Encode Persons for a full explanation of<nameLink>.

¶Families

Stow enjoys listing all the members of a

person’s family (below is an

extremeexample). Family entries often take a bit of time because the entries of all family members need to be updated. For example, let’s pretend that in the 1598 Survey of London, Joane is said to be married to Robert Dunne. Then by the 1633 edition, she has also married Richard Stoneley, John Branche, and has had more children. Not only will you have to potentially add new people (husbands and children) to PERS1.xml, but you will have to check if any of the people already exist, and, if so, update their entries:

<person xml:id="BRAN13" sex="2">

<persName type="hist">

<reg>Joane Branche (née Wylkynson)</reg>

<forename>Joane</forename>

<surname>Wylkynson</surname>

<surname>Branche</surname>

<surname>Dunne</surname>

<surname>Stoneley</surname>

</persName>

<note><p>Wife of <name ref="mol:DUNN3">Robert Dunne</name>, <name ref="mol:STON15">Richard Stoneley</name>, and <name ref="mol:BRAN4">John Branche</name>. Mother of <name ref="mol:BRAN12">Anne Branche</name>, <name ref="mol:DUNN4">Sir Daniel Dunne</name>, <name ref="mol:DUNN5">Samuel Dunne</name>, <name ref="mol:DUNN6">William Dunne</name>, <name ref="mol:DANT2">Dorothie Dauntrey</name>, and <name ref="mol:HIGH7">Anne Higham</name>. Daughter of <name ref="mol:WILK4">John Wylkynson</name>.</p>

</note>

</person>

In the example above, find:

<persName type="hist">

<reg>Joane Branche (née Wylkynson)</reg>

<forename>Joane</forename>

<surname>Wylkynson</surname>

<surname>Branche</surname>

<surname>Dunne</surname>

<surname>Stoneley</surname>

</persName>

<note><p>Wife of <name ref="mol:DUNN3">Robert Dunne</name>, <name ref="mol:STON15">Richard Stoneley</name>, and <name ref="mol:BRAN4">John Branche</name>. Mother of <name ref="mol:BRAN12">Anne Branche</name>, <name ref="mol:DUNN4">Sir Daniel Dunne</name>, <name ref="mol:DUNN5">Samuel Dunne</name>, <name ref="mol:DUNN6">William Dunne</name>, <name ref="mol:DANT2">Dorothie Dauntrey</name>, and <name ref="mol:HIGH7">Anne Higham</name>. Daughter of <name ref="mol:WILK4">John Wylkynson</name>.</p>

</note>

</person>

-

née Wylkynson: in the text, we learn that Joane is the daughter of John Wylkynson and is the wife of Robert Dunne, Richard Stoneley, and John Branche. We have given her the last nameBranche

because he was her last husband (theoretically, she likely died asJoane Branche

). Since we know her father’s name wasWylkynson,

we include(née Wylkynson)

in the<reg>. As you can see above, all of Joane’s surnames are also individually tagged with<surname>. See Encode Persons for a full explanation ofnée

and<surname>. -

Dorothie DauntreyandAnne Higham: note thatDorothie Dauntrey

andAnne Higham

are listed as their<reg>names and not asDorothie Branche

andAnne Branche.

¶Member of a Livery Company

Often all Stow includes about a person is

their name and occupation, which is often the livery company they

belonged to:

<person xml:id="BART14" sex="1">

<persName type="hist">

<reg>William Barton</reg>

<forename>William</forename>

<surname>Barton</surname>

</persName>

<note><p>Member of the <name type="org" ref="mol:MERC3">Mercers’ Company</name>. Buried at <ref target="mol:STLA5">St. Laurence, Jewry</ref>.</p>

</note>

</person>

In the example above, find:

<persName type="hist">

<reg>William Barton</reg>

<forename>William</forename>

<surname>Barton</surname>

</persName>

<note><p>Member of the <name type="org" ref="mol:MERC3">Mercers’ Company</name>. Buried at <ref target="mol:STLA5">St. Laurence, Jewry</ref>.</p>

</note>

</person>

-

Buried at: to document a place of burial, writeBuried at

and the location’s name from the A-Z Index (i.e., the title of the location’s page).

¶Unknown Person

Sometimes there is very little information on a person. In these cases,

we say

Denizen of London(if we at least know that):

<person xml:id="NORM9" sex="1">

<persName type="hist">

<reg>John Norman</reg>

<forename>John</forename>

<surname>Norman</surname>

</persName>

<note><p>Denizen of <ref target="mol:LOND5">London</ref>. Not to be confused with <name ref="mol:NORM1">Sir John Norman</name> or <name ref="mol:NORM6">John Norman</name>.</p>

</note>

</person>

In the example above, find:

<persName type="hist">

<reg>John Norman</reg>

<forename>John</forename>

<surname>Norman</surname>

</persName>

<note><p>Denizen of <ref target="mol:LOND5">London</ref>. Not to be confused with <name ref="mol:NORM1">Sir John Norman</name> or <name ref="mol:NORM6">John Norman</name>.</p>

</note>

</person>

-

Not to be confused with: if there are multiple people with the same name, it is helpful to addNot to be confused with.

This is also how we clear the diagnostic errorPossible duplicate personography entries.

If we know nothing about a person, we add this boilerplate text:

<person xml:id="MALV1" sex="1">

<persName type="hist">

<reg>John Malverne</reg>

<forename>John</forename>

<surname>Malverne</surname>

</persName>

<note><p>MoEML has not yet added biographical content for this person. The editors welcome research leads from qualified individuals. Please <ref target="mailto:london@uvic.ca">contact us</ref> for further information.</p>

</note>

</person>

<persName type="hist">

<reg>John Malverne</reg>

<forename>John</forename>

<surname>Malverne</surname>

</persName>

<note><p>MoEML has not yet added biographical content for this person. The editors welcome research leads from qualified individuals. Please <ref target="mailto:london@uvic.ca">contact us</ref> for further information.</p>

</note>

</person>

¶Possibly the same person?

Sometimes it is hard to tell whether two people are the same. For

example, maybe you come across

John Skinnerin your ward, but there is not enough information to know that he matches the

John Skinneralready present in PERS1.xml. In this case, we add

Possibly the same person asso readers know to look at both entries:

<person xml:id="SKIN8" sex="1">

<persName type="hist">

<reg>John Skinner</reg>

<forename>John</forename>

<surname>Skinner</surname>

</persName>

<note><p>Son of <name ref="mol:SKIN4">Sir Thomas Skinner</name>. Possibly the same person as <name ref="mol:SKIN7">John Skinner</name>.</p>

</note>

</person>

<persName type="hist">

<reg>John Skinner</reg>

<forename>John</forename>

<surname>Skinner</surname>

</persName>

<note><p>Son of <name ref="mol:SKIN4">Sir Thomas Skinner</name>. Possibly the same person as <name ref="mol:SKIN7">John Skinner</name>.</p>

</note>

</person>

¶Latin Epitaphs

Beware: if Stow walks into a church in the

1633 Survey of London, he will interrupt his

narrative to copy down pages of latin epitaphs. If a person only appears

in a latin epitaph, we add

Latin epitaph in Stow 1633to the end of their biographical statement:

<note><p>Rector of <ref target="mol:STNI3">St. Nicholas Olave</ref>.

Buried at <ref target="mol:STNI3">St. Nicholas Olave</ref>.

Latin epitaph in Stow 1633.</p>

</note>

</note>

¶Common Mistakes

Compare these biographical statements to the examples explained above and

examples in Encode

Persons. Can you tell what should be fixed?

Question 1:

<p>Recipient of a tower by <ref target="mol:BAYN1">Baynard’s

Castle</ref>, given by <name ref="mol:EDWA3">king Edward the

thirde</name> in the <date when-custom="r_EDWA3_02" datingMethod="mol:regnal" calendar="mol:regnal">second year

of his reign</date>.</p>

Answer: king Edward the thirdeshould be modernized to

Edward III(whenever someone is mentioned in PERS1.xml, their

<reg> name is used).

<p>Recipient of a tower by <ref target="mol:BAYN1">Baynard’s

Castle</ref>, given by <name ref="mol:EDWA3">Edward

III</name> in the <date when-custom="r_EDWA3_02" datingMethod="mol:regnal" calendar="mol:regnal">second year

of his reign</date>.</p>

Question 2:

<p>Wife of <name ref="mol:DANI10">John Daniel</name> and mother of

<name ref="mol:DANI11">Gerard Daniel</name>. Buried at <ref target="mol:STMA16">St. Margaret Moses</ref>.</p>

Answer: When listing family members, every relation should

start a new sentence.

<p>Wife of <name ref="mol:DANI10">John Daniel</name>. Mother of

<name ref="mol:DANI11">Gerard Daniel</name>. Buried at <ref target="mol:STMA16">St. Margaret Moses</ref>.</p>

Question 3:

<p>Founder of a chantry at the <ref target="mol:STIMI9">Parish

Church of St. Mildred Bread Street</ref> in <date when-custom="1419" datingMethod="mol:julianSic" calendar="mol:julianSic">1419</date>.</p>

Answer: When mentioning a location in a biographical statement,

use its name from the A-Z Index (i.e., the title of the location’s page)

for consistency.

<p>Founder of a chantry at <ref target="mol:STIM9">St. Mildred,

Bread Street</ref> in <date when-custom="1419" datingMethod="mol:julianSic" calendar="mol:julianSic">1419</date>.</p>

Cite this page

MLA citation

.

MoEML Quickstart.The Map of Early Modern London, edited by , U of Victoria, 15 Sep. 2020, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/moeml_quickstart.htm. Draft.

Chicago citation

.

MoEML Quickstart.The Map of Early Modern London. Ed. . Victoria: University of Victoria. Accessed September 15, 2020. https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/moeml_quickstart.htm. Draft.

APA citation

2020. MoEML Quickstart. In (Ed), The Map of Early Modern London. Victoria: University of Victoria. Retrieved from https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/moeml_quickstart.htm. Draft.

RIS file (for RefMan, EndNote etc.)

Provider: University of Victoria Database: The Map of Early Modern London Content: text/plain; charset="utf-8" TY - ELEC A1 - LeBere, Kate ED - Jenstad, Janelle T1 - MoEML Quickstart T2 - The Map of Early Modern London PY - 2020 DA - 2020/09/15 CY - Victoria PB - University of Victoria LA - English UR - https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/moeml_quickstart.htm UR - https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/xml/standalone/moeml_quickstart.xml TY - UNP ER -

RefWorks

RT Unpublished Material SR Electronic(1) A1 LeBere, Kate A6 Jenstad, Janelle T1 MoEML Quickstart T2 The Map of Early Modern London WP 2020 FD 2020/09/15 RD 2020/09/15 PP Victoria PB University of Victoria LA English OL English LK https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/moeml_quickstart.htm

TEI citation

<bibl type="mla"><author><name ref="#LEBE1"><surname>LeBere</surname>, <forename>Kate</forename></name></author>.

<title level="a">MoEML Quickstart</title>. <title level="m">The Map of Early Modern

London</title>, edited by <editor><name ref="#JENS1"><forename>Janelle</forename>

<surname>Jenstad</surname></name></editor>, <publisher>U of Victoria</publisher>,

<date when="2020-09-15">15 Sep. 2020</date>, <ref target="https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/moeml_quickstart.htm">mapoflondon.uvic.ca/moeml_quickstart.htm</ref>.

Draft.</bibl>

Personography

-

Kate LeBere

KL

Project Manager, 2020-present. Assistant Project Manager, 2019-2020. Research Assistant, 2018-present. Kate LeBere completed an honours BA in History with a minor in English at the University of Victoria in 2020. During her degree she published in The Corvette (2018), The Albatross (2019), and PLVS VLTRA (2020) and presented at the English Undergraduate Conference (2019) and Qualicum History Conference (2020). While her primary research focus was sixteenth and seventeenth century England, she developed a keen interest in Old English and Early Middle English translation and completed her honours thesis on Soviet ballet during the Russian Cultural Revolution.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Copy Editor

-

Date Encoder

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geo-Coordinate Researcher

-

Markup Editor

-

Name Encoder

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcription Proofreader

Contributions by this author

Kate LeBere is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Kate LeBere is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Joey Takeda

JT

Programmer, 2018-present. Junior Programmer, 2015-2017. Research Assistant, 2014-2017. Joey Takeda was a graduate student at the University of British Columbia in the Department of English (Science and Technology research stream). He completed his BA honours in English (with a minor in Women’s Studies) at the University of Victoria in 2016. His primary research interests included diasporic and indigenous Canadian and American literature, critical theory, cultural studies, and the digital humanities.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Introduction

-

Author of Stub

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Copy Editor and Revisor

-

Data Manager

-

Date Encoder

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Bibliography)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Agas)

-

Junior Programmer

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Encoder

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Post-conversion processing and markup correction

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Second Author

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Editor

Contributions by this author

Joey Takeda is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Joey Takeda is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Janelle Jenstad

JJ

Janelle Jenstad is Associate Professor of English at the University of Victoria, Director of The Map of Early Modern London, and PI of Linked Early Modern Drama Online. She has taught at Queen’s University, the Summer Academy at the Stratford Festival, the University of Windsor, and the University of Victoria. With Jennifer Roberts-Smith and Mark Kaethler, she co-edited Shakespeare’s Language in Digital Media (Routledge). She has prepared a documentary edition of John Stow’s A Survey of London (1598 text) for MoEML and is currently editing The Merchant of Venice (with Stephen Wittek) and Heywood’s 2 If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody for DRE. Her articles have appeared in Digital Humanities Quarterly, Renaissance and Reformation,Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Early Modern Literary Studies, Elizabethan Theatre, Shakespeare Bulletin: A Journal of Performance Criticism, and The Silver Society Journal. Her book chapters have appeared (or will appear) in Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society (Brill, 2004), Shakespeare, Language and the Stage, The Fifth Wall: Approaches to Shakespeare from Criticism, Performance and Theatre Studies (Arden/Thomson Learning, 2005), Approaches to Teaching Othello (Modern Language Association, 2005), Performing Maternity in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2007), New Directions in the Geohumanities: Art, Text, and History at the Edge of Place (Routledge, 2011), Early Modern Studies and the Digital Turn (Iter, 2016), Teaching Early Modern English Literature from the Archives (MLA, 2015), Placing Names: Enriching and Integrating Gazetteers (Indiana, 2016), Making Things and Drawing Boundaries (Minnesota, 2017), and Rethinking Shakespeare’s Source Study: Audiences, Authors, and Digital Technologies (Routledge, 2018).Roles played in the project

-

Annotator

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Stub

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

Author of Textual Introduction

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Copyeditor

-

Course Instructor

-

Course Supervisor

-

Course supervisor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Structure and Toponyms)

-

Final Markup Editor

-

GIS Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Modern)

-

Geographical Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Main Transcriber

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Project Director

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Name Encoder

-

Peer Reviewer

-

Primary Author

-

Project Director

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Reviewer

-

Reviser

-

Revising Author

-

Second Author

-

Second Encoder

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Janelle Jenstad is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Janelle Jenstad is mentioned in the following documents:

Janelle Jenstad authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Jenstad, Janelle.

Building a Gazetteer for Early Modern London, 1550-1650.

Placing Names. Ed. Merrick Lex Berman, Ruth Mostern, and Humphrey Southall. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 2016. 129-145. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

The Burse and the Merchant’s Purse: Coin, Credit, and the Nation in Heywood’s 2 If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody.

The Elizabethan Theatre XV. Ed. C.E. McGee and A.L. Magnusson. Toronto: P.D. Meany, 2002. 181–202. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Early Modern Literary Studies 8.2 (2002): 5.1–26..The City Cannot Hold You

: Social Conversion in the Goldsmith’s Shop. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

The Silver Society Journal 10 (1998): 40–43.The Gouldesmythes Storehowse

: Early Evidence for Specialisation. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Lying-in Like a Countess: The Lisle Letters, the Cecil Family, and A Chaste Maid in Cheapside.

Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 34 (2004): 373–403. doi:10.1215/10829636–34–2–373. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Public Glory, Private Gilt: The Goldsmiths’ Company and the Spectacle of Punishment.

Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society. Ed. Anne Goldgar and Robert Frost. Leiden: Brill, 2004. 191–217. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Smock Secrets: Birth and Women’s Mysteries on the Early Modern Stage.

Performing Maternity in Early Modern England. Ed. Katherine Moncrief and Kathryn McPherson. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007. 87–99. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Using Early Modern Maps in Literary Studies: Views and Caveats from London.

GeoHumanities: Art, History, Text at the Edge of Place. Ed. Michael Dear, James Ketchum, Sarah Luria, and Doug Richardson. London: Routledge, 2011. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Versioning John Stow’s A Survey of London, or, What’s New in 1618 and 1633?.

Janelle Jenstad Blog. https://janellejenstad.com/2013/03/20/versioning-john-stows-a-survey-of-london-or-whats-new-in-1618-and-1633/. -

Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. Ed. Janelle Jenstad. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ & nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. Ed. Janelle Jenstad and the MoEML Team. MoEML. Transcribed. Web.

-

-

Martin D. Holmes

MDH

Programmer at the University of Victoria Humanities Computing and Media Centre (HCMC). Martin ported the MOL project from its original PHP incarnation to a pure eXist database implementation in the fall of 2011. Since then, he has been lead programmer on the project and has also been responsible for maintaining the project schemas. He was a co-applicant on MoEML’s 2012 SSHRC Insight Grant.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Author of abstract

-

Conceptor

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Markup editor

-

Name Encoder

-

Post-conversion and Markup Editor

-

Post-conversion processing and markup correction

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

Contributions by this author

Martin D. Holmes is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Martin D. Holmes is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Henry le Waleys is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Stow

(b. between 1524 and 1525, d. 1605)Historian and author of A Survey of London. Husband of Elizabeth Stow.John Stow is mentioned in the following documents:

John Stow authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Blome, Richard.

Aldersgate Ward and St. Martins le Grand Liberty Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. M3r and sig. M4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Aldgate Ward with its Division into Parishes. Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections & Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H3r and sig. H4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Billingsgate Ward and Bridge Ward Within with it’s Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. Y2r and sig. Y3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Bishopsgate-street Ward. Taken from the Last Survey and Corrected.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. N1r and sig. N2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Bread Street Ward and Cardwainter Ward with its Division into Parishes Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. B3r and sig. B4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Broad Street Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections and Additions, & Cornhill Ward with its Divisions into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, &c.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. P2r and sig. P3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Cheape Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig.D1r and sig. D2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Coleman Street Ward and Bashishaw Ward Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. G2r and sig. G3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Cow Cross being St Sepulchers Parish Without and the Charterhouse.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H2v and sig. H3r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Creplegate Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, with Additions, and Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. I3r and sig. I4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Farrington Ward Without, with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections & Amendments.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. 2F3r and sig. 2F4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Lambeth and Christ Church Parish Southwark. Taken from ye last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. Z1r and sig. Z2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Langborne Ward with its Division into Parishes. Corrected from the Last Survey. & Candlewick Ward with its Division into Parishes. Corrected from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. U3r and sig. U4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Map of St. Gilles’s Cripple Gate. Without. With Large Additions and Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H2v and sig. H3r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Map of the Parish of St. Dunstans Stepney, als. Stebunheath Divided into Hamlets.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. F3r and sig. F4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Map of the Parish of St Mary White Chappel and a Map of the Parish of St Katherines by the Tower.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. F2r and sig. F3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of Lime Street Ward. Taken from ye Last Surveys & Corrected.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. M1r and sig. M2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of St. Andrews Holborn Parish as well Within the Liberty as Without.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. 2I1r and sig. 2I2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parishes of St. Clements Danes, St. Mary Savoy; with the Rolls Liberty and Lincolns Inn, Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig.O4v and sig. O1r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St. Anns. Taken from the last Survey, with Correction, and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. L2v and sig. L3r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St. Giles’s in the Fields Taken from the Last Servey, with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. K1v and sig. K2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Margarets Westminster Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig.H3v and sig. H4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Martins in the Fields Taken from ye Last Survey with Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. I1v and sig. I2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Pauls Covent Garden Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. L3v and sig. L4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Saviours Southwark and St Georges taken from ye last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. D1r and sig.D2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

The Parish of St. James Clerkenwell taken from ye last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H3v and sig. H4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

The Parish of St. James’s, Westminster Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. K4v and sig. L1r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

The Parish of St Johns Wapping. The Parish of St Paul Shadwell.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. E2r and sig. E3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Portsoken Ward being Part of the Parish of St. Buttolphs Aldgate, taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections and Additions.