The Curtain

¶Abstract

In 1577, the Curtain, the second purpose-built London playhouse, arose in Shoreditch, just north of the City of London.1 The Curtain, a polygonal amphitheatre, became a major venue for theatrical and other entertainments

until at least 1622. The building may have stood on the site until as late as 1698. Most major playing companies, including the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, the Queen’s Men, and Prince Charles’s Men, played there. It is the likely site for the premiere of Shakespeare’s plays Romeo and Juliet and Henry V.

¶The Neighbourhood and the Site

Bounded by Moorfields to the south, Bishopsgate Street to the east, and Finsbury Fields to the west, Shoreditch is located on the north side of the City of London. It remained a collection of manors, farms, fields, and religious houses into the

16th century. The Curtain was built on the south side of the current Hewett Street, near Bishopsgate Street (Bird). In the 1590s, William Shakespeare occupied a house nearby on Bishopsgate Street (Mander). The neighbourhood name references a polluted stream, sometimes called Sewersditch, which ran from St. Leonard’s Church to Holy Well Lane, now known as High Street. Shoreditch followed Roman roads near Kingsland Road, a continuation of Ermine Street , and Old Street, a continuation of Waitling or Watling Street (Campbell). The majority of Shoreditch occupants resided on or near Holy Well Lane.

Shoreditch also had a well known nunnery, Holywell Priory, from the 12th to 16th centuries (Bowsher,

Holywell Priory232). The Priory was the ninth richest in all of England (Bull). Following the Reformation, the Priory was dissolved in 1539 (Mander). Later, the neighbourhood featured manor houses for the wealthy, such as Stratton House and Stone House (Bull). Recent research on the history of first purpose-built playhouse, the Theatre, features useful new historical maps, as well as a schematic that shows the proximity of the Curtain to the Priory and other important structures in the area.

To the north, St. Leonard’s Church still stands at the corner of Bishopsgate Street and Old Street (Mander). No firm date exists for the building of the original medieval church, but in engravings

it appears to date from the 15th century (Bird). It featured a tower with up to five bells (Bird). James Bird points to John Stow (Bird 74), who says that between the north corner of the field west of the High Street and

the church

sometime stood a Crosse, now a Smithes Forge, dividing three wayes.The 1598 edition of A Survey notes that the Curtain and the Theatre were built nearby:

neare thereunto are builded two publique houses for the acting and shewe of Comedies, Tragedies, and Histories, for recreation. Whereof the one is called the Courtein, the other the Theatre: both standing on the Southwest side towards the field(Stow 349 ; qtd in Collier 263-64). This reference to the two playhouses was removed from the 1603 edition of A Survey.

By the 1590s, St. Leonard’s Church has become associated with actors. Both Cuthbert Burbage and Richard Burbage, actors and sons of theatre owner (and builder of the Theatre) James Burbage, who was also manager of the Curtain, were buried there (Bird). St. Leonard’s is thus sometimes known as the

actor’s churchof London (Mander). The original church became structurally unsound in the early 18th century and was demolished in 1736. It was rebuilt in the same location in 1740 (Thornbury).

After 1577, vice and criminality, including prostitution, began to overtake the neighbourhood.

As early as 1579, moralists complained about the malign influence the theatres in Shoreditch had on the public, with a character, Reason, in Thomas Twyne’s pamphlet Physic against Fortune, a translation of Italian poet Petrarch’s De Remediis utriusque Fortunae, noting that both the Theatre and Curtain were

well knowen to be enimies to good manners; for looke who goeth there evyl returneth worse(Twyne sig. F4; qtd in Chambers 202). John Northbrooke complained about the malign influence of playhouses on the title page of his 1578 Treatise that attacks

vaine Playes(Northbrooke; qtd. in Berry 377).

In 1584, incidents at the Theatre and the Curtain caused significant civil unrest. Correspondence between Queen Elizabeth I’s Lord Chamberlain, William Cecil, Lord Burghley and William Fleetwood, recorder of London, detail a near-riot on 14 June 1584. Fleetwood comments that

very nere the Theatre or Curten at the tyme of the Playes,an apprentice sleeping in one of the nearby fields was pestered by a gentleman, which resulted in a fistfight. The following day, other apprentices threatened to riot and an unnamed number were arrested. Fleetwood ordered the arrest of the Theatre’s owner, James Burbage. Burbage’s status as a member of the playing company sponsored by Henry Carey, Lord Hunsdon meant that he could refuse arrest, and he noted that he was

my Lo of hunsdons man.Burbage agreed to appear in court the next day (BL Lansdowne MS 41; qtd. in Berry 345).

One further reference to the dubious nature of the Curtain and its environs comes from a 1613 satirical text by George Wither that mentions derisively that a foolish young lover, Momus,

can cull, / From plaies he heard at Curtaine or at the Bull, / And yet is fine coy Mistress Marry-Muffe, / The soonest taken with such broken stuffe.Momus goes to

the Curtaine’ to pick up hints at fooling, and notes Gap in transcription. Reason: Editorial omission for reasons of length or relevance. Use only in quotations in born-digital documents.[…] downenot quotations from the plays but

that action Gap in transcription. Reason: Editorial omission for reasons of length or relevance. Use only in quotations in born-digital documents.[…] that likes him best(Wither sig. D3v; qtd. in Chambers 404).

¶Theatre Architecture

Built by Henry Laneman (also known as Henry Lanman) in 1577, the Curtain arose a mere 200 yards from its neighbour, the Theatre, built the year before by James Burbage (Gurr 31; Bowsher, Shakespeare’s London Theatreland 55, 62). Very close geographically, they were perhaps even closer in design. No documentation

exists for the specific design of the Curtain, but it may have copied its neighbour in at least some details if we accept Gurr’s

narrative. A similar design may also have been used for the Rose, Swan, and Globe theatres (Gurr 132). Details about the excavation of the Theatre from the Museum of London Archeology provide important background, since the two

playhouses were in such close proximity and had shared management (Bowsher, Shakespeare’s London Theatreland 63; see also LAARC CNU02).

The Curtain was a polygonal amphitheatre, built of timber and finished with lime and plaster

(Adams 77-78). It was probably the Curtain that Shakespeare describes as

this unworthy Scaffold Gap in transcription. Reason: Editorial omission for reasons of length or relevance. Use only in quotations in born-digital documents.[…] this Cock-pit Gap in transcription. Reason: Editorial omission for reasons of length or relevance. Use only in quotations in born-digital documents.[…] this Woodden O’in the prologue to Henry V, which seems to have been first performed there (Stern 15; Shakespeare 14-16). Its dimensions remain in question, although excavations are underway (see below, Excavation and Site). As a comparison, the Rose’s foundations, unearthed in 1989, reveal a building about 22 metres in diameter (

The Rose). The Theatre, excavated in 2011, was a 14-sided polygonal building with an almost identical diameter of about 22 metres (Bowsher, Shakespeare’s London Theatreland 58).

The Curtain, modeled after these theatres, as well as popular animal baiting rings such as the

Bear Garden, was a purpose-built, public theatre designed for plays. In a baiting house, animals

such as bulls and bears occupied the ground floor yard and the spectators used the

galleries.2 Playhouses used the yard to pack in patrons instead. In addition to the yard, the

Curtain had three galleries, each of which had wooden steps for seating. The galleries and

stage were covered by the roof, while the yard was open to the elements. A protected

view was an advantage that cost viewers more: one penny was charged to enter the yard,

and then an additional penny was collected to enter the galleries. A final penny gained

a seat close to the stage and a cushion (Gurr 17). A recent collaboration between media firm Cloak and Dagger Studios and Museum of

London Archaeology produced a video animation,

Shoreditch 1595,which shows the current approximation of the appearance of an Elizabethan playhouse.

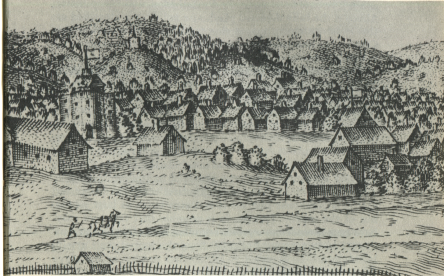

One likely image of the Curtain has been identified. In

The View of the Citty of London from the North towards the South,a prominent building fitting the description of the Curtain appears on the left half of the image. It is tall, has three upper levels, a loft at the top, staircases on the sides, and a flagpole. Depending on scholarly opinion of the date that The View was engraved, the building is either the Theatre or the Curtain (Berry,

The View of London196-97).

The View of the Cittye of London from the North towards the Sowth,reprinted in Berry, The First Public Playhouse.

Unlike its predecessor the Theatre (whose timbers became the Globe), the Curtain had longevity. Records indicate the Curtain in use for performances by acting companies at least until 1625, nearly 50 years after its construction (Wickham 67). Ashley Thorndike speculates that the Curtain was most likely still standing at the closing of the theatres in 1642 (Thorndike 45). Some scholars assert it was still standing until destroyed by the Great Fire in 1666, while others claim that it was not pulled down until 1698 (

Curtain,ShaLT).

¶Human Connections: Ownership and Theatre Companies

James Burbage built the Curtain, but actors also owned shares in the building. The Curtain appears in the will of Thomas Pope. Pope, a member of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, left his share of the Globe and the Curtain to his heirs in his will dated 22 July 1603 (EMLoT; see also Honigmann and Brock 70). John Underwood, a member of the King’s Men, likewise left his share of the Globe, the Blackfriars, and the Curtain to heirs in his will dated 4 October 1624 (EMLoT; see also Honigmann and Brock 143).

In 1597—1598, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, which included Will Kempe as their clown, used the Curtain for their performances. The 1599 second quarto of Romeo and Juliet features the stage direction

enter Will Kempjust prior to the character Peter’s lines in 4.5 (Q2, K3v, qtd in EMLoT). Collier concludes that Kemp must have played on the Curtain stage (Collier 89). Another of Shakespeare’s comic actors also may have performed there. Robert Armin once referred to himself as

Clonnico de Curtanio Snuffor the Clown of the Curtain Snuff (Chambers 403).

After the Lord Chamberlain’s Men moved to the Globe in Southwark, some public records indicate that other companies played at the Curtain. In 1601, Oxford’s Men seem to have been the target of an order from the Privy Council, who asked the Middlesex county justices of the peace to halt the performance of

an unnamed play at the Curtain. The play apparently represented

the persons of some gentlemen of good desert and quality that are yet alive,although it did so in

an obscure manner(Berry,

The View of London414). Beginning in 1603, the Queen Anne’s Men, also known as Worcester’s Men, performed various plays at the Curtain until 1609 when they relocated to the Red Bull. However, the Privy Council ordered in April 1604 that the King’s Men, the Queen’s Men, and the Prince Charles’s Men be allowed to perform at the Globe, Fortune, and Curtain (Berry,

The View of London414). Starting in 1622, the Prince Charles’s Men used the Curtain, the Red Bull, and the Cockpit until they disbanded in 1625 (Gurr 55-67; Bowsher, Shakespeare’s London Theatreland 64). Although the building was standing in 1642 and perhaps as late as 1660, or even 1698, no other companies have been discovered in connection with the Curtain.

¶Human Connections: Plays and Playwrights

Between 1585 and 1642, various well known playwrights had their plays performed at the Curtain. Most famously, scholars such as Tiffany Stern and Julian Bowsher conjecture that

Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet first debuted at the Curtain in a performance by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men in 1598. This date arises in part from a passage by Shakespeare’s contemporary, John Marston, whose Tenth Satire has a habitual playgoer, Luscus, who is asked:

Luscus, what’s plaid today? I’faith now I knowe:I see thy lips abroach, from whence doth flowNaught but pure Juliet and RomeoSay who acts best? Drusus or Roscio?Now I have him, that ne’er of aught did speakeBut when of plays or players he did treat;And speakes in print, at least whate’er he saysIs warranted by Curtain plaudities.

(Marston sig. H4r; transcribed in Furness 409)

According to Tiffany Stern,

the few narratives that relate to the Curtain always suggest that there was something unglamorous about the place,and that audiences mined plays like

Romeo and Juliet for verbal tidbits that they can use in their later, post-play flirtations(Stern 79), clearly referring to the Marston passage above. The following year, Shakespeare’s final history play Henry V played there, which likely features the Curtain as

this Wooden O(Shakespeare 14).

Other notable playwrights whose work appeared on the Curtain’s stage include Ben Jonson, Thomas Heywood, William Rowley, John Day, and George Wilkins. Few plays are certainly known to have been performed at the Curtain, with only a handful well known. The earliest documented play performed at the theatre

was Ben Jonson’s Every Man in his Humor in 1598, with William Shakespeare in the cast (EMLoT; Bowsher, Shakespeare’s London Theatreland 64). The next few years in the Curtain’s history are a blank. No playbills survive, and there are no title-page ascriptions.

The next known play surfaced in 1603—Thomas Heywood’s A Woman Kill’d with Kindness. In 1607, The Travels of Three English Brothers was performed by the Queen Anne’s Men (EMLoT).

¶Known Plays Performed at the Curtain

| Performance Date | Title | Author | Date of First Publication3 | Playing Company | DEEP Number | Wiggins Number4 |

| 1598-1599 | Romeo and Juliet | William Shakespeare | 1597 | Lord Chamberlain’s Men | 234 | 987 |

| 1599 | Henry V | William Shakespeare | 1600 | Lord Chamberlain’s Men | 252/288 | 1183 |

| 1598 | Every Man in His Humour | Ben Jonson | 1601 | Lord Chamberlain’s Men | 313 | 1143 |

| 1603 | A Woman Kill’d With Kindness | Thomas Heywood | 1607 | Worcester’s Men5 | 502 | |

| 1607 | The Travels of the Three English Brothers | William Rowley, John Day, George Wilkins | 1607 | Queen Anne’s Men | 482 | |

| 1615 | The Hector of Germany, or The Palsgrave | Wentworth Smith | 1615 | Unidentified6 | 623 |

¶Archaeology: Excavation and Site in Modern London

The precise location of the Curtain was unknown in modern London until the foundations were discovered in 2012 during improvement construction in the Borough of Hackney. Historians knew the general

location, and so a commemorative plaque commissioned by Hackney London Borough Council

was placed in 1993 high on an exterior brick wall at 18 Hewett Street. The plaque was placed at the

Curtain’s purported location, but there was no physical supporting evidence. The plaque proved

to be amazingly accurate: it was approximately 266 feet (82 metres) from the plaque

to the entrance of the site of the actual theatre. The site sits at the intersection

of Hewett Street and Curtain Road with the entrance of the Curtain appearing to be on the western side of the building, now situated against Curtain

Road below the Victorian era pub, The Horse and Groom. Next to the Horse and Groom

is a car repair shop with an investigation pit that had, unknowingly, exposed the

foundations of the Curtain even before excavation began (Kennedy). Bowsher believes that the stage was situated on the eastern side of this parcel

(Bowsher, Shakespeare’s London Theatreland 67).

Limited excavation began at the site in 2012, carried out by archaeologists from the Museum of London Archaeology. According to

reports on the archaeological investigation, the remains of the Curtain’s foundation appear to have escaped serious interference and are

remarkably well-preserved(Kennedy). The surviving base of the foundation is made of bricks and is currently buried about 3 metres below ground level. An outer yard was also discovered in the excavation. This yard was

paved with sheep knuckle bones that could date from the theatre or slightly later housing(Kennedy). Unlike the Rose excavation in 1988, so far only a few artifacts have been found at the site. The only artifacts found so far that date to Shakespeare’s time have been shards of pottery from a pipe:

other small finds, including fragments of china and wall tile, were rather later in date(Baillie).

¶More from MoEML: Further Resources

The Curtain Theatre Shoreditch: A site produced by the community of modern Shoreditch, which has a vested interest

in any future development of the Curtain site.

For information about the Curtain, a modern map marking the site where it once stood, and a walking tour that will

take you to the site, visit the Shakespearean London Theatres (ShaLT) page on the Curtain.

In 2016, archaeological excavations in Shoreditch revealed that the Curtain was rectangular in shape, instead of polygonal (as initially believed, and as this

article suggests). For more information, see Maev Kennedy,

Excavation Finds Early Shakespeare Theatre was Rectangular,published in The Guardian on 17 May 2016.

Notes

- It was preceded by John Rastell’s stage in Finsbury, the 1567 Red Lion in Stepney, and the nearby Theatre, built in 1576. (JJ)↑

- See our topic page—

Bearbaiting in Early Modern London

— for more information. (JT)↑ - Publication dates taken from DEEP. (JT)↑

- The five published volumes of Wiggins’s British Drama cover 1533-1602. Forthcoming volumes will cover the rest of the period up to 1642. (JT)↑

- Low certainty. ()↑

a Company of Young-men of the Citie

()↑

References

-

Citation

Adams, Joseph Quincy. Shakespearean Playhouses. Gloucester: Peter Smith, 1917. Remediated by Internet Archive.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Baillie, Philip.Pre-Globe Shakespeare Theater Unearthed in London.

Reuters. Thomson Reuters, 6 June 2012. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-britain-shakespeare/pre-globe-shakespeare-theater-unearthed-in-london-idUSBRE8550LH20120606.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Berry, Herbert.Aspects of the Design and Use of the First Public Playhouse.

The First Public Playhouse: The Theatre in Shoreditch 1576–1598. Ed. Herbert Berry. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1979. 29–46. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Berry, Herbert.The View of London from the North and the Playhouses in Holywell.

Shakespeare Survey 53 (2000): 196–212. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521781140.017.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Bird, James, ed. Shoreditch. Vol. 8 of Survey of London. London: London County Council, 1922. Remediated by British History Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Bowsher, Julian.Holywell Priory and The Theatre in Shoreditch.

London Archaeologist 11.9 (2007): 231–234.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Bowsher, Julian. Shakespeare’s London Theatreland: Archaeology, History, and Drama. London: MoLA, 2012.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Bull, Raoul, Simon Davis, Hana Lewis, Christopher Phillpotts, and Aaron Birchenough. Holywell Priory and the Development of Shoreditch to c. 1600: Archaeology from the London Overground East London Line. London: MoLA, 2011. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

.

Shoreditch Street.

The Map of Early Modern London, edited by , U of Victoria, 15 Sep. 2020, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/SHOR2.htm. -

Citation

Chambers, E.K. The Elizabethan Stage. 4 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1923. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Collier, John. The History of English Dramatic Poetry. New York: AMSP, 1970. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Curtain Theatre.

Shakespeare’s London Theatres. Ed. Gabriel Egan. De Montfort U. http://shalt.dmu.ac.uk/locations/curtain-1577-1625.html.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Davies, Callan.The Curtain Rises (21 July 2018).

Before Shakespeare. U of Roehampton. https://beforeshakespeare.com/2018/06/20/the-curtain-rises-21-july-2018/.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

DEEP: Database of Early English Playbooks. Ed. Alan B. Farmer and Zachary Lesser. Open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Egan, Gabriel, ed. Shakespearean London Theatres. De Montfort U and Victoria & Albert Museum. http://shalt.dmu.ac.uk/.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Furness, Horace, ed. Romeo and Juliet: New Variorum Edition. By William Shakespeare. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, 1913. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Gurr, Andrew. Playgoing in Shakespeare’s London. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2004. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Honigmann, E.A.J.Review of Henslowe’s Diary.

The Review of English Studies 13.51 (1962): 298–300. doi:10.1093/res/XIII.51.298.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Kennedy, Maev.Shakespeare’s Curtain Theatre Unearthed in East London.

The Guardian. Guardian News & Media, 6 June 2012. http://www.theguardian.com/culture/2012/jun/06/shakespeare-curtain-theatre-shoreditch-east-lonfon.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

London Archaeological Archive and Research Centre. MoLA. https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/collections/other-collection-databases-and-libraries/museum-london-archaeological-archive.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Mander, David.Local History: Shoreditch.

British National Archives. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/tudorhackney/localhistory/lochsh.asp.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

This item is cited in the following documents:

-

.

The Rose.

The Map of Early Modern London, edited by , U of Victoria, 15 Sep. 2020, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/ROSE6.htm. INP. -

Citation

Shakespeare, William. Henry V. Ed. James D. Mardock. Internet Shakespeare Editions. 11 May 2012. Open.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Stern, Tiffany. Making Shakespeare: From Stage to Page. London: Routledge, 2004. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ & nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. Ed. Janelle Jenstad and the MoEML Team. MoEML. Transcribed. Web.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

, and .

Survey of London: Cordwainer Street Ward.

The Map of Early Modern London, edited by , U of Victoria, 15 Sep. 2020, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/stow_1598_CORD1.htm. -

Citation

Syme, Holger.Post-Curtain Theatre History.

Dispositio: Most Theatre, Then and Now, There and Here. http://www.dispositio.net/archives/2262.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Thornbury, Walter. Old and New London. 6 vols. London, 1878. Remediated by British History Online.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Thorndike, Ashley H. Shakespeare’s Theater. New York: MacMillan Co. 1916. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Twyne, Thomas. Phisicke against fortune, aswell prosperous, as aduerse. London: 1579. STC 19809. EEBO. Subscr.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Wickham, Glynne. Early English Stages: 1300 to 1660. 3 vols. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1972. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

Wiggins, Martin, and Catherine Richardson. British Drama 1533–1642: A Catalogue. 4 vols. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2011. Print.This item is cited in the following documents:

-

Citation

This item is cited in the following documents:

Cite this page

MLA citation

.

The Curtain.The Map of Early Modern London, edited by , U of Victoria, 15 Sep. 2020, mapoflondon.uvic.ca/CURT2.htm.

Chicago citation

.

The Curtain.The Map of Early Modern London. Ed. . Victoria: University of Victoria. Accessed September 15, 2020. https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/CURT2.htm.

APA citation

. 2020. The Curtain. In (Ed), The Map of Early Modern London. Victoria: University of Victoria. Retrieved from https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/CURT2.htm.

RIS file (for RefMan, EndNote etc.)

Provider: University of Victoria Database: The Map of Early Modern London Content: text/plain; charset="utf-8" TY - ELEC A1 - Utah Valley University English 463R Spring 2014 Students ED - Jenstad, Janelle T1 - The Curtain T2 - The Map of Early Modern London PY - 2020 DA - 2020/09/15 CY - Victoria PB - University of Victoria LA - English UR - https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/CURT2.htm UR - https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/xml/standalone/CURT2.xml ER -

RefWorks

RT Web Page SR Electronic(1) A1 Utah Valley University English 463R Spring 2014 Students A6 Jenstad, Janelle T1 The Curtain T2 The Map of Early Modern London WP 2020 FD 2020/09/15 RD 2020/09/15 PP Victoria PB University of Victoria LA English OL English LK https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/CURT2.htm

TEI citation

<bibl type="mla"><author><name ref="#UTVU1" type="org">Utah Valley University English

463R Spring 2014 Students</name></author>. <title level="a">The Curtain</title>. <title

level="m">The Map of Early Modern London</title>, edited by <editor><name ref="#JENS1"><forename>Janelle</forename>

<surname>Jenstad</surname></name></editor>, <publisher>U of Victoria</publisher>,

<date when="2020-09-15">15 Sep. 2020</date>, <ref target="https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/CURT2.htm">mapoflondon.uvic.ca/CURT2.htm</ref>.</bibl>

Personography

-

Joey Takeda

JT

Programmer, 2018-present. Junior Programmer, 2015-2017. Research Assistant, 2014-2017. Joey Takeda was a graduate student at the University of British Columbia in the Department of English (Science and Technology research stream). He completed his BA honours in English (with a minor in Women’s Studies) at the University of Victoria in 2016. His primary research interests included diasporic and indigenous Canadian and American literature, critical theory, cultural studies, and the digital humanities.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Introduction

-

Author of Stub

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Copy Editor and Revisor

-

Data Manager

-

Date Encoder

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Bibliography)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Agas)

-

Junior Programmer

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Encoder

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Post-conversion processing and markup correction

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Second Author

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Editor

Contributions by this author

Joey Takeda is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Joey Takeda is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Tye Landels-Gruenewald

TLG

Data Manager, 2015-2016. Research Assistant, 2013-2015. Tye completed his undergraduate honours degree in English at the University of Victoria in 2015.Roles played in the project

-

Author

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

MoEML Researcher

-

Name Encoder

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

Contributions by this author

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Tye Landels-Gruenewald is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kim McLean-Fiander

KMF

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach, 2015–present. Associate Project Director, 2015–present. Assistant Project Director, 2013-2014. MoEML Research Fellow, 2013. Kim McLean-Fiander comes to The Map of Early Modern London from the Cultures of Knowledge digital humanities project at the University of Oxford, where she was the editor of Early Modern Letters Online, an open-access union catalogue and editorial interface for correspondence from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. She is currently Co-Director of a sister project to EMLO called Women’s Early Modern Letters Online (WEMLO). In the past, she held an internship with the curator of manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library, completed a doctorate at Oxford on paratext and early modern women writers, and worked a number of years for the Bodleian Libraries and as a freelance editor. She has a passion for rare books and manuscripts as social and material artifacts, and is interested in the development of digital resources that will improve access to these materials while ensuring their ongoing preservation and conservation. An avid traveler, Kim has always loved both London and maps, and so is particularly delighted to be able to bring her early modern scholarly expertise to bear on the MoEML project.Roles played in the project

-

Associate Project Director

-

Author

-

Author of MoEML Introduction

-

CSS Editor

-

Compiler

-

Contributor

-

Copy Editor

-

Data Contributor

-

Data Manager

-

Director of Pedagogy and Outreach

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (People)

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Managing Editor

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Architect

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Research Fellow

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Proofreader

-

Second Author

-

Secondary Author

-

Secondary Editor

-

Toponymist

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Kim McLean-Fiander is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Kim McLean-Fiander is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Janelle Jenstad

JJ

Janelle Jenstad is Associate Professor of English at the University of Victoria, Director of The Map of Early Modern London, and PI of Linked Early Modern Drama Online. She has taught at Queen’s University, the Summer Academy at the Stratford Festival, the University of Windsor, and the University of Victoria. With Jennifer Roberts-Smith and Mark Kaethler, she co-edited Shakespeare’s Language in Digital Media (Routledge). She has prepared a documentary edition of John Stow’s A Survey of London (1598 text) for MoEML and is currently editing The Merchant of Venice (with Stephen Wittek) and Heywood’s 2 If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody for DRE. Her articles have appeared in Digital Humanities Quarterly, Renaissance and Reformation,Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Early Modern Literary Studies, Elizabethan Theatre, Shakespeare Bulletin: A Journal of Performance Criticism, and The Silver Society Journal. Her book chapters have appeared (or will appear) in Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society (Brill, 2004), Shakespeare, Language and the Stage, The Fifth Wall: Approaches to Shakespeare from Criticism, Performance and Theatre Studies (Arden/Thomson Learning, 2005), Approaches to Teaching Othello (Modern Language Association, 2005), Performing Maternity in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2007), New Directions in the Geohumanities: Art, Text, and History at the Edge of Place (Routledge, 2011), Early Modern Studies and the Digital Turn (Iter, 2016), Teaching Early Modern English Literature from the Archives (MLA, 2015), Placing Names: Enriching and Integrating Gazetteers (Indiana, 2016), Making Things and Drawing Boundaries (Minnesota, 2017), and Rethinking Shakespeare’s Source Study: Audiences, Authors, and Digital Technologies (Routledge, 2018).Roles played in the project

-

Annotator

-

Author

-

Author of Abstract

-

Author of Stub

-

Author of Term Descriptions

-

Author of Textual Introduction

-

Compiler

-

Conceptor

-

Copy Editor

-

Copyeditor

-

Course Instructor

-

Course Supervisor

-

Course supervisor

-

Data Manager

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Encoder (Structure and Toponyms)

-

Final Markup Editor

-

GIS Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist

-

Geographic Information Specialist (Modern)

-

Geographical Information Specialist

-

JCURA Co-Supervisor

-

Main Transcriber

-

Markup Editor

-

Metadata Co-Architect

-

MoEML Project Director

-

MoEML Transcriber

-

Name Encoder

-

Peer Reviewer

-

Primary Author

-

Project Director

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

-

Reviewer

-

Reviser

-

Revising Author

-

Second Author

-

Second Encoder

-

Toponymist

-

Transcriber

-

Transcription Proofreader

-

Vetter

Contributions by this author

Janelle Jenstad is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Janelle Jenstad is mentioned in the following documents:

Janelle Jenstad authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Jenstad, Janelle.

Building a Gazetteer for Early Modern London, 1550-1650.

Placing Names. Ed. Merrick Lex Berman, Ruth Mostern, and Humphrey Southall. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 2016. 129-145. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

The Burse and the Merchant’s Purse: Coin, Credit, and the Nation in Heywood’s 2 If You Know Not Me You Know Nobody.

The Elizabethan Theatre XV. Ed. C.E. McGee and A.L. Magnusson. Toronto: P.D. Meany, 2002. 181–202. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Early Modern Literary Studies 8.2 (2002): 5.1–26..The City Cannot Hold You

: Social Conversion in the Goldsmith’s Shop. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

The Silver Society Journal 10 (1998): 40–43.The Gouldesmythes Storehowse

: Early Evidence for Specialisation. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Lying-in Like a Countess: The Lisle Letters, the Cecil Family, and A Chaste Maid in Cheapside.

Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 34 (2004): 373–403. doi:10.1215/10829636–34–2–373. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Public Glory, Private Gilt: The Goldsmiths’ Company and the Spectacle of Punishment.

Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society. Ed. Anne Goldgar and Robert Frost. Leiden: Brill, 2004. 191–217. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Smock Secrets: Birth and Women’s Mysteries on the Early Modern Stage.

Performing Maternity in Early Modern England. Ed. Katherine Moncrief and Kathryn McPherson. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007. 87–99. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Using Early Modern Maps in Literary Studies: Views and Caveats from London.

GeoHumanities: Art, History, Text at the Edge of Place. Ed. Michael Dear, James Ketchum, Sarah Luria, and Doug Richardson. London: Routledge, 2011. Print. -

Jenstad, Janelle.

Versioning John Stow’s A Survey of London, or, What’s New in 1618 and 1633?.

Janelle Jenstad Blog. https://janellejenstad.com/2013/03/20/versioning-john-stows-a-survey-of-london-or-whats-new-in-1618-and-1633/. -

Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. Ed. Janelle Jenstad. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ & nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. Ed. Janelle Jenstad and the MoEML Team. MoEML. Transcribed. Web.

-

-

Martin D. Holmes

MDH

Programmer at the University of Victoria Humanities Computing and Media Centre (HCMC). Martin ported the MOL project from its original PHP incarnation to a pure eXist database implementation in the fall of 2011. Since then, he has been lead programmer on the project and has also been responsible for maintaining the project schemas. He was a co-applicant on MoEML’s 2012 SSHRC Insight Grant.Roles played in the project

-

Abstract Author

-

Author

-

Author of abstract

-

Conceptor

-

Editor

-

Encoder

-

Markup editor

-

Name Encoder

-

Post-conversion and Markup Editor

-

Post-conversion processing and markup correction

-

Programmer

-

Proofreader

-

Researcher

Contributions by this author

Martin D. Holmes is a member of the following organizations and/or groups:

Martin D. Holmes is mentioned in the following documents:

-

-

Kate McPherson

Kate McPherson is a MoEML Pedagogical Partner. She is Professor of English at Utah Valley University. She is co-editor, with Kathryn Moncrief and Sarah Enloe of Shakespeare Expressed: Page, Stage, and Classroom in Shakespeare and His Contemporaries (Fairleigh Dickinson, 2013); and with Kathryn Moncrief of two other edited collections, Performing Pedagogy in Early Modern England: Gender, Instruction, and Performance (Ashgate, 2011) and Performing Maternity in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2008). She has published numerous articles on early modern maternity in scholarly journals as well. An award-winning teacher, Kate is also Resident Scholar for the Grassroots Shakespeare Company, an original practices performance troupe begun by two UVU students.Roles played in the project

-

Author of Abstract

-

Guest Editor

Kate McPherson is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Robert Armin is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Richard Burbage is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Cuthbert Burbage

(b. between 1564 and 1565, d. 1636)Actor. Son of James Burbage. Brother of Richard Burbage.Cuthbert Burbage is mentioned in the following documents:

-

James Burbage is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Henry Carey

(b. 4 March 1526, d. 23 July 1596)First Baron Hunsdon. Lord Chamberlain of Elizabeth I’s household. Patron of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men.Henry Carey is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Sir William Cecil

(b. between 1520 and 1521, d. 1598)First Baron Burghley. Husband of Mildred Cecil. Father of Anne Cecil.Sir William Cecil is mentioned in the following documents:

Sir William Cecil authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Cecil, William. A Collection of State Papers Relating to Affairs in the Reign of Queen Elizabeth, from the year 1571 to 1596. Transcribed from Original Papers and other Authentic Memorials never before published. Ed. William Murdin. London: William Bowyer in White-fryars, 1759.

-

John Day is mentioned in the following documents:

John Day authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Day, John [and Henry Chettle]. The Blind-beggar of Bednal Green. London: R. Pollard and Tho. Dring, 1659. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth This numeral is a Roman numeral. The Arabic equivalent is 1I Queen of England Queen of Ireland Gloriana Good Queen Bess

(b. 7 September 1533, d. 24 March 1603)Queen of England and Ireland 1558-1603.Elizabeth I is mentioned in the following documents:

-

William Fleetwood is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thomas Heywood is mentioned in the following documents:

Thomas Heywood authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Heywood, Thomas. The Captives; or, The Lost Recovered. Ed. Alexander Corbin Judson. New Haven: Yale UP, 1921. Print.

-

Heywood, Thomas. The First and Second Parts of King Edward IV. Ed. Richard Rowland. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2005. The Revels Plays.

-

Heywood, Thomas. The Second Part of, If you know not me, you know no bodie. VVith the building of the Royall Exchange: And the Famous Victorie of Queene Elizabeth, in the Yeare 1588. London, 1606. STC 13336. EEBO. Web. Subscr.

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. Ed. Vittorio Gabrieli and Giorgio Melchiori. Revels Plays. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1990. Print.

-

Thomas Heywood Heywood’s Dramatic Works. 6 vols. Ed. W.J. Alexander. London: John Pearson, 1874. Print.

-

Ben Jonson is mentioned in the following documents:

Ben Jonson authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Chapman, George, Ben Jonson, and John Marston. Eastward Ho! Ed. R.W. Van Fossen. New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Print.

-

Dekker, Thomas, Stephen Harrison, Ben Jonson, and Thomas Middleton. The Whole Royal and Magnificent Entertainment of King James through the City of London, 15 March 1604, with the Arches of Triumph. Ed. R. Malcolm Smuts. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works. Gen. ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. 219–79.

-

Gifford, William, ed. The Works of Ben Jonson. By Ben Jonson. Vol. 1. London: Nichol, 1816. Remediated by Internet Archive.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Alchemist. London: New Mermaids, 1991. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Bartholomew Fair. Ed. E.A. Horsman. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1979. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Bartholomew Fair. Ed. Suzanne Gossett, based on The Revels Plays edition ed. E.A. Horsman. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2000. Revels Student Editions. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. B. Ion: his part of King Iames his royall and magnificent entertainement through his honorable cittie of London, Thurseday the 15. of March. 1603 so much as was presented in the first and last of their triumphall arch’s. London, 1604. STC 14756. EEBO.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Complete Poetry of Ben Jonson. Ed. William B. Hunter. Stuart Edtions. New York: New YorkUP, 1963.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Devil is an Ass. Ed. Peter Happé. Manchester and New York: Manchester UP, 1996. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Epicene. Ed. Richard Dutton. Revels Plays. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2004. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. Every Man Out of His Humour. Ed. Helen Ostovich. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2001. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben. The First, of Blacknesse, Personated at the Court, at White-hall, on the Twelfth Night, 1605. The Characters of Two Royall Masques: The One of Blacknesse, the Other of Beautie. Personated by the Most Magnificent of Queenes Anne Queene of Great Britaine, &c. with her Honorable Ladyes, 1605 and 1608 at White-hall. London : For Thomas Thorp, and are to be Sold at the Signe of the Tigers Head in Paules Church-yard, 1608. Sig. A3r-C2r. STC 14761. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Jonson, Ben. Oberon, The Faery Prince. The Workes of Benjamin Jonson. Vol. 1. London: Will Stansby, 1616. Sig. 4N2r-2N6r. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Staple of Newes. The Works. Vol. 2. London: Printed by I.B. for Robert Allot, 1631. Sig. 2A1r-2J2v. Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Jonson, Ben. The Staple of News. Ed. Anthony Parr. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Revels Plays. Print.

-

Jonson, Ben.

To Penshurst.

The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt, Carol T. Christ, Alfred David, Barbara K. Lewalski, Lawrence Lipking, George M. Logan, Deidre Shauna Lynch, Katharine Eisaman Maus, James Noggle, Jahan Ramazani, Catherine Robson, James Simpson, Jon Stallworthy, Jack Stillinger, and M. H. Abrams. 9th ed. Vol. B. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2012. 1547. -

Jonson, Ben. The vvorkes of Beniamin Ionson. Containing these playes, viz. 1 Bartholomew Fayre. 2 The staple of newes. 3 The Divell is an asse. London, 1641. EEBO. Reprint. Subscr. STC 14754.

-

William Kempe is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Henry Lanman

Original proprietor of the Curtain.Henry Lanman is mentioned in the following documents:

-

John Marston is mentioned in the following documents:

John Marston authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Chapman, George, Ben Jonson, and John Marston. Eastward Ho! Ed. R.W. Van Fossen. New York: Manchester UP, 1999. Print.

-

John Northbrooke is mentioned in the following documents:

-

Thomas Pope is mentioned in the following documents:

-

William Shakespeare is mentioned in the following documents:

William Shakespeare authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Munday, Anthony, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, and William Shakespeare. Sir Thomas More. Ed. Vittorio Gabrieli and Giorgio Melchiori. Revels Plays. Manchester; New York: Manchester UP, 1990. Print.

-

Shakespeare, William. All’s Well That Ends Well. Ed. Helen Ostovich. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.

-

Shakespeare, William. Antony and Cleopatra. Ed. Randall Martin. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Comedy of Errors. Ed. Matthew Steggle. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.

-

Shakespeare, William. The first part of the contention betwixt the two famous houses of Yorke and Lancaster with the death of the good Duke Humphrey: and the banishment and death of the Duke of Suffolke, and the tragicall end of the proud Cardinall of VVinchester, vvith the notable rebellion of Iacke Cade: and the Duke of Yorkes first claime vnto the crowne. London, 1594. STC26099. [Transcription available from Internet Shakespeare Editions. Web.]

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry IV, Part 1. Ed. Rosemary Gaby. Internet Shakespeare Editions. 11 May 2012. Open.

-

Shakespeare, William. Henry V. Ed. James D. Mardock. Internet Shakespeare Editions. 11 May 2012. Open.

-

Shakespeare, William. King Lear. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 1201–54.

-

Shakespeare, William. King Richard III. Ed. James R. Siemon. London: Methuen, 2009. The Arden Shakespeare.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Life of King Henry the Eighth. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 919–64.

-

Shakespeare, William. Measure for Measure. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 414–54.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. Ed. Janelle Jenstad. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.

-

Shakespeare, William. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Ed. Suzanne Westfall. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.

-

Shakespeare, William. Mr. VVilliam Shakespeares comedies, histories, & tragedies Published according to the true originall copies. London, 1623. STC 22273. [Book facsimiles available from Internet Shakespeare Editions. Web.]

-

Shakespeare, William. Much Ado About Nothing. Ed. Grechen Minton. Internet Shakespeare Editions. 11 May 2012. Open.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Passionate Pilgrim. Ed. Hardy M. Cook. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Phoenix and the Turtle. Ed. Hardy M. Cook. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.

-

Shakespeare, William. Richard II. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 740–83.

-

Shakespeare, William. Richard the Third (Modern). Ed. Adrian Kiernander. Internet Shakespeare Editions. 6 March 2012. Open.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Second Part of King Henry the Sixth. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 552–984.

-

Shakespeare, William. The Tempest. Ed. Brent Whitted and Paul Yachnin. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.

-

Shakespeare, William. Titus Andronicus. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004. 966–1004.

-

Shakespeare, William. Troilus and Cressida. Ed. W. L. Godshalk. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.

-

Shakespeare, William. Twelfth Night. Ed. David Carnegie and Mark Houlahan. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.

-

Shakespeare, William. Two Gentlemen of Verona. Ed. Melissa Walter. Internet Shakespeare Editions. Open.

-

John Stow

(b. between 1524 and 1525, d. 1605)Historian and author of A Survey of London. Husband of Elizabeth Stow.John Stow is mentioned in the following documents:

John Stow authored or edited the following items in MoEML’s bibliography:

-

Blome, Richard.

Aldersgate Ward and St. Martins le Grand Liberty Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. M3r and sig. M4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Aldgate Ward with its Division into Parishes. Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections & Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H3r and sig. H4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Billingsgate Ward and Bridge Ward Within with it’s Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. Y2r and sig. Y3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Bishopsgate-street Ward. Taken from the Last Survey and Corrected.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. N1r and sig. N2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Bread Street Ward and Cardwainter Ward with its Division into Parishes Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. B3r and sig. B4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Broad Street Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections and Additions, & Cornhill Ward with its Divisions into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, &c.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. P2r and sig. P3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Cheape Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig.D1r and sig. D2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Coleman Street Ward and Bashishaw Ward Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. G2r and sig. G3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Cow Cross being St Sepulchers Parish Without and the Charterhouse.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H2v and sig. H3r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Creplegate Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, with Additions, and Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. I3r and sig. I4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Farrington Ward Without, with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections & Amendments.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. 2F3r and sig. 2F4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Lambeth and Christ Church Parish Southwark. Taken from ye last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. Z1r and sig. Z2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Langborne Ward with its Division into Parishes. Corrected from the Last Survey. & Candlewick Ward with its Division into Parishes. Corrected from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. U3r and sig. U4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Map of St. Gilles’s Cripple Gate. Without. With Large Additions and Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H2v and sig. H3r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Map of the Parish of St. Dunstans Stepney, als. Stebunheath Divided into Hamlets.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. F3r and sig. F4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Map of the Parish of St Mary White Chappel and a Map of the Parish of St Katherines by the Tower.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. F2r and sig. F3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of Lime Street Ward. Taken from ye Last Surveys & Corrected.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. M1r and sig. M2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of St. Andrews Holborn Parish as well Within the Liberty as Without.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. 2I1r and sig. 2I2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parishes of St. Clements Danes, St. Mary Savoy; with the Rolls Liberty and Lincolns Inn, Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig.O4v and sig. O1r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St. Anns. Taken from the last Survey, with Correction, and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. L2v and sig. L3r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St. Giles’s in the Fields Taken from the Last Servey, with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. K1v and sig. K2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Margarets Westminster Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig.H3v and sig. H4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Martins in the Fields Taken from ye Last Survey with Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. I1v and sig. I2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Pauls Covent Garden Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. L3v and sig. L4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

A Mapp of the Parish of St Saviours Southwark and St Georges taken from ye last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. D1r and sig.D2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

The Parish of St. James Clerkenwell taken from ye last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H3v and sig. H4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

The Parish of St. James’s, Westminster Taken from the Last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. K4v and sig. L1r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

The Parish of St Johns Wapping. The Parish of St Paul Shadwell.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. E2r and sig. E3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Portsoken Ward being Part of the Parish of St. Buttolphs Aldgate, taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections and Additions.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. B1v and sig. B2r. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Queen Hith Ward and Vintry Ward with their Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. 2C4r and sig. 2D1v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Shoreditch Norton Folgate, and Crepplegate Without Taken from ye Last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. G1r and sig. G2v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Spitt Fields and Plans Adjacent Taken from Last Survey with Locations.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. F4r and sig. G1v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

St. Olave and St. Mary Magdalens Bermondsey Southwark Taken from ye last Survey with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. C2r and sig.C3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Tower Street Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. E2r and sig. E3v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

Walbrook Ward and Dowgate Ward with its Division into Parishes, Taken from the Last Surveys.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. 2B3r and sig. 2B4v. [See more information about this map.] -

Blome, Richard.

The Wards of Farington Within and Baynards Castle with its Divisions into Parishes, Taken from the Last Survey, with Corrections.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. Q2r and sig. Q3v. [See more information about this map.] -

The City of London as in Q. Elizabeth’s Time.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Frontispiece. -

A Map of the Tower Liberty.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. H4v and sig. I1r. [See more information about this map.] -

A New Plan of the City of London, Westminster and Southwark.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 1. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Frontispiece. -

Pearl, Valerie.

Introduction.

A Survey of London. By John Stow. Ed. H.B. Wheatley. London: Everyman’s Library, 1987. v–xii. Print. -

Pullen, John.

A Map of the Parish of St Mary Rotherhith.

A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original, Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of those Cities. By John Stow and John Strype. Vol. 2. London: A. Churchill, J. Knapton, R. Knaplock, J. Walthoe, E. Horne, B. Tooke, D. Midwinter, B. Cowse, R. Robinson, and T. Ward, 1720. Insert between sig. Z3r and sig. Z4r. [See more information about this map.] -

Stow, John, Anthony Munday, and Henry Holland. THE SVRVAY of LONDON: Containing, The Originall, Antiquitie, Encrease, and more Moderne Estate of the sayd Famous Citie. As also, the Rule and Gouernment thereof (both Ecclesiasticall and Temporall) from time to time. With a briefe Relation of all the memorable Monuments, and other especiall Obseruations, both in and about the same CITIE. Written in the yeere 1598. by Iohn Stow, Citizen of London. Since then, continued, corrected and much enlarged, with many rare and worthy Notes, both of Venerable Antiquity, and later memorie; such, as were neuer published before this present yeere 1618. London: George Purslowe, 1618. STC 23344. Yale University Library copy Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Stow, John, Anthony Munday, and Humphrey Dyson. THE SURVEY OF LONDON: CONTAINING The Original, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of that City, Methodically set down. With a Memorial of those famouser Acts of Charity, which for publick and Pious Vses have been bestowed by many Worshipfull Citizens and Benefactors. As also all the Ancient and Modern Monuments erected in the Churches, not only of those two famous Cities, LONDON and WESTMINSTER, but (now newly added) Four miles compass. Begun first by the pains and industry of John Stow, in the year 1598. Afterwards inlarged by the care and diligence of A.M. in the year 1618. And now compleatly finished by the study &labour of A.M., H.D. and others, this present year 1633. Whereunto, besides many Additions (as appears by the Contents) are annexed divers Alphabetical Tables, especially two, The first, an index of Things. The second, a Concordance of Names. London: Printed for Nicholas Bourne, 1633. STC 23345.5. Harvard University Library copy Reprint. Early English Books Online. Web.

-

Stow, John. The chronicles of England from Brute vnto this present yeare of Christ. 1580. Collected by Iohn Stow citizen of London. London, 1580. Rpt. EEBO. Web.

-

Stow, John. A Summarie of the Chronicles of England. Diligently Collected, Abridged, & Continued vnto this Present Yeere of Christ, 1598. London: Imprinted by Richard Bradocke, 1598. Rpt. EEBO. Web.

-

Stow, John. A suruay of London· Conteyning the originall, antiquity, increase, moderne estate, and description of that city, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow citizen of London. Since by the same author increased, with diuers rare notes of antiquity, and published in the yeare, 1603. Also an apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that citie, the greatnesse thereof. VVith an appendix, contayning in Latine Libellum de situ & nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. London: John Windet, 1603. STC 23343. U of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign Campus) copy Reprint. Early English Books Online. Web.

-

Stow, John, The survey of London contayning the originall, increase, moderne estate, and government of that city, methodically set downe. With a memoriall of those famouser acts of charity, which for publicke and pious vses have beene bestowed by many worshipfull citizens and benefactors. As also all the ancient and moderne monuments erected in the churches, not onely of those two famous cities, London and Westminster, but (now newly added) foure miles compasse. Begunne first by the paines and industry of Iohn Stovv, in the yeere 1598. Afterwards inlarged by the care and diligence of A.M. in the yeere 1618. And now completely finished by the study and labour of A.M. H.D. and others, this present yeere 1633. Whereunto, besides many additions (as appeares by the contents) are annexed divers alphabeticall tables; especially two: the first, an index of things. The second, a concordance of names. London: Printed by Elizabeth Purslovv for Nicholas Bourne, 1633. STC 23345. U of Victoria copy.

-

Stow, John, The survey of London contayning the originall, increase, moderne estate, and government of that city, methodically set downe. With a memoriall of those famouser acts of charity, which for publicke and pious vses have beene bestowed by many worshipfull citizens and benefactors. As also all the ancient and moderne monuments erected in the churches, not onely of those two famous cities, London and Westminster, but (now newly added) foure miles compasse. Begunne first by the paines and industry of Iohn Stovv, in the yeere 1598. Afterwards inlarged by the care and diligence of A.M. in the yeere 1618. And now completely finished by the study and labour of A.M. H.D. and others, this present yeere 1633. Whereunto, besides many additions (as appeares by the contents) are annexed divers alphabeticall tables; especially two: the first, an index of things. The second, a concordance of names. London: Printed by Elizabeth Purslovv [i.e., Purslow] for Nicholas Bourne, 1633. STC 23345. British Library copy Reprint. EEBO. Web.

-

Stow, John. A Survey of London. Reprinted from the Text of 1603. Ed. Charles Lethbridge Kingsford. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1908. Remediated by British History Online.

-

Stow, John. A Survey of London. Reprinted from the Text of 1603. Ed. Charles Lethbridge Kingsford. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1908. Remediated by British History Online. [Kingsford edition, courtesy of The Centre for Metropolitan History. Articles written 2011 or later cite from this searchable transcription.]

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ &nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. 23341. Transcribed by EEBO-TCP.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ & nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. Ed. Janelle Jenstad and the MoEML Team. MoEML. Transcribed. Web.

-

Stow, John. A SVRVAY OF LONDON. Contayning the Originall, Antiquity, Increase, Moderne estate, and description of that Citie, written in the yeare 1598. by Iohn Stow Citizen of London. Also an Apologie (or defence) against the opinion of some men, concerning that Citie, the greatnesse thereof. With an Appendix, containing in Latine, Libellum de situ &nobilitate Londini: written by William Fitzstephen, in the raigne of Henry the second. Folger Shakespeare Library.